|

Throwback Thursday: Yellow to Welcome Spring, with Alarie Tennille Every winter I grow weary of the gray, though this year I have an adorable gray kitten in the house to keep my spirits up. Spring arrives late in the Midwest. In Virginia, where I was raised, flowers have been blooming for weeks. So I’ve selected yellow works of art from the archive that inspired writing to lift our moods. Alarie ** Wendy Taylor Carlisle: And Simply Read We get a double dose of sunshine from the girl’s daffodil dress to the pleasures of reading. Small wonder I couldn’t resist buying a print of this Fragonard painting when I was in high school. I’ve always had my nose in a book. https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/and-simply-read-by-wendy-t-carlisle ** Sheila Wellehan: My Life with Matisse Wellehan made my selection process easy by celebrating the vibrant colors and subjects Matisse is known for. https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/my-life-with-matisse-by-sheila-wellehan ** Judy Kronenfeld: Unfinished Painting The painting welcomes us into a new day with it’s soft glow of yellow and serenity. Then Kronenfeld makes us wish to linger there with her powerful last stanza. We’re trespassing, but relish the chance to do so. https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/unfinished-painting-by-judy-kronenfeld ** Mary McCarthy: Vincent When I think of vivid yellow canvases, Van Gogh is the first artist I think of, which is one just one reason McCarthy was brilliant to use “Vincent” as the title instead of giving the wheat field or crows the credit for the painting’s electric pulse and that killer ending. https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/vincent-by-mary-mccarthy ** Bill Waters: A Found Poem, Submit You may disagree about yellow being the main focus of this painting. After all, there’s a fair amount of Luzajic’s flirty pink and dramatic black to hold the painting down to earth. Yet I applaud the yellow for setting the playful tone that Waters bounced around like a balloon. https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/submit-a-found-poem-by-bill-waters ** John Skeen: Inside and Out The bird in the photo doesn’t just sing spring. He is spring, and he brought that feeling to John Skeen, too. https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/inside-and-out-by-john-skeen ** Barbara Lydecker Crane: Painting Henry You might be surprised I chose this selection. It’s not the bright, springy, feel good moment caught in the other paintings, and the color is more greedy gold. But the insider joke and mockery of Henry VIII make me laugh. https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/painting-henry-by-barbara-lydecker-crane ** Kate Young: How Lovely Yellow Is! It’s fitting to end this throwback admirationg of yellow with a poem specifically targetting the color and capturing the spirit and rooms in which Van Gogh lived and breathed his art. https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/how-lovely-yellow-is-by-kate-young Be a guest editor for a Throwback Thursday! Pick up to 10 favourite or random posts from the archives of The Ekphrastic Review. Use the format you see above: title, name of author, a sentence or two about your choice, and the link. Include a bio and if you wish, a note to readers about the Review, your relationship to the journal, ekphrastic writing in general, or any other relevant subject. Put THROWBACK THURSDAYS in the subject line and send to theekphrasticreview@gmail.com. Along with your picks, send a vintage photo of yourself!

0 Comments

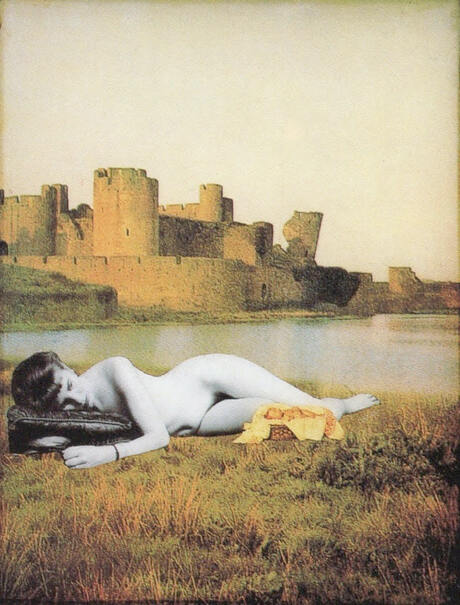

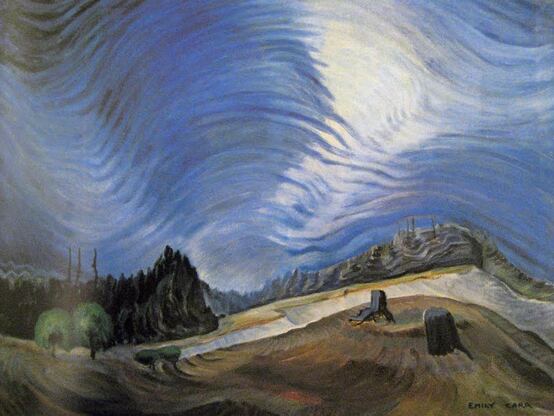

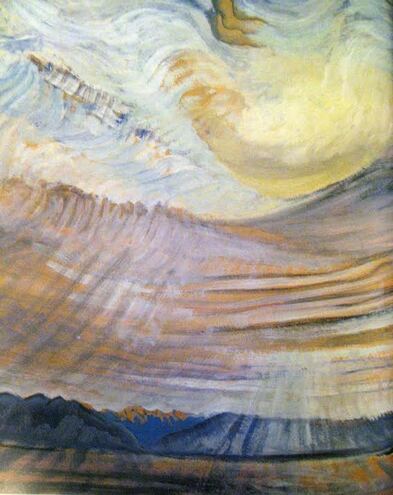

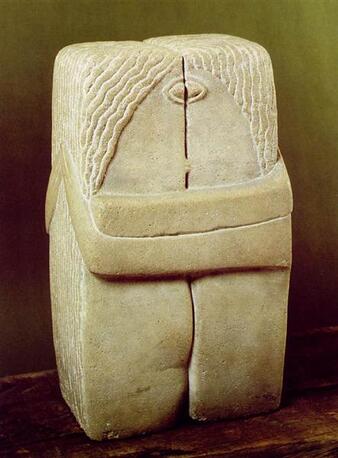

I’ll Say I Know Buddy, And They’ll Let Me Eat In Finally lost Nick. My bet, he’s down Tennessee. Always finds bus fare to go cryin’ to his momma, Nicky does. I’m meeting Buddy, I’ll say. Or maybe, I’m waiting for Buddy. Maybe put my jacket down first. No, just order, don’t give ‘em time to think. Coke and steak‘n’fries, real hot. Got some money today, yes sir. I’ll pay for my sizzling plate, scoop up that change real easy, like I do it every day, and slip my ass into a seat, casual. Use that little wooden pick like a silver fork. Like Buddy’s on his way any second. Maybe even strike up a little conversation. They’re not bad guys, I know. And I’m a- ok today. Kalliopy Paleos This piece was inspired by Fish and Chips, by Brett Amory (USA) 2015. Click here to view it. Kalliopy Paleos is a teacher of French with roots in Greece, France, and the US. Her poems and micros have recently been seen in the Tupelo Press 30/30 challenge and Mediterranean Poetry. Interests include 18th century history and staring at trees while thinking. Loneliness Naked on the Grass The collagist cuts precisely around her edges careful not to damage hair, fingers, skin, vulnerable as a snail without shell, a pale tree whose outer bark has peeled. She won’t be needing clothes or shoes. He offers her a pillow, searches his files for the perfect bed of grass. He pastes her down. She must look away from the castle. She doesn’t belong inside stone walls feasting on stuffed swan, peacock, mutton and tarts–banquets of the wealthy. She doesn’t hunger, almost like a mannequin, a gift for men. But he wasn’t thinking of them. No one will question his intentions, a reclining nude is the tradition. His scissors hiss as he cuts out contents for the basket: a newborn. He never meant to harm her daughter. He was poor all his life, drawn to women beyond his touch. Haven’t you ever wanted someone you couldn’t have? Carrie Albert Carrie Albert is a writer and visual artist. Sometimes these merge. Her works have been published widely in journals and anthologies, most recently: The Protest Diaries (B Cubed Press), Gyroscope Review, Sleet, Plumtree Homeless Edition and upcoming in Canticles and Spheres, Propertius Press. She lives in Seattle with her papier-mâché animals. A Game of Patience The door clicks closed behind me. Julia glances up, poised mid-game, a playing card held aloft in her delicate, elegant, long, tapered, thin, white fingers. In that pregnant moment between now and the future, no sound. My eyes and brain freeze the scene, burning it acid-sharp in memory. This is a moment to which we can never return. She sits in her virginal, soft-folded, cornflower dress, cotton-trimmed with angular severity. She will make a good nurse. She has whiled away this sultry afternoon, patiently. She is faintly puzzled now. I have left the fields. Left the men to the burning, harvest heat. They will surely slack. The circle of the green-baize table traps the circle of cards. On the table, two apples, one rich, ripe and tempting, the other a bitter gall. From beyond the open window, a hot draught eddies across the room, Stirs a stem of barley, carelessly abandoned to its fate A poppy bud, prematurely picked, falls to the floor Like Janus, I stand at the thresh But the door to ‘before’, is closed. Now we can only look forward to Future or no future. The die has been cast The Black King revealed. Julia’s bare and barren fingers are poised, Taut, ready to turn the next card She is expectant, This woman with burnished, copper hair and stiff spine. She knows I have not brought a marriage proposal Thought that may follow, Sooner than we expected. With impassive gaze and oblivious expectancy, she waits, To speak is to sin To break this moment The burden of my news weighs heavy on my heart Still, Julia waits with practised poise. ‘They’ve declared war’ Slowly, she blinks and turns her head To the scene outside Where the men toil in the poppy-stained fields Until their card is called. Helen How Helen How is an award-winning writer living on the Isle of Arran in Scotland. Her family roots are Gaelic-speaking Scots and she enjoys performing and writing to share the culture of both North-East England, where she grew up, and Scotland, her chosen home. A professional writer and teacher, she now devotes her time to creative writing. Much of her work embodies the haunting tone of childhood memories and the stories told to her by her parents and grandparents. She takes her inspiration from folklore, the landscape and art. Force Fields (Emily Carr, Canadian artist & writer, 1878-1945) Stand still. The forest knows where you are. You must let it find you. David Wagoner i. Sky The subject is movement —and sky: a rising surge of repetitions, brush strokes like auras, arcs rushing up through the undergrowth, across the gravel pit past loggers’ culls beyond the vertical spars of trees. Today, Vancouver’s children pay crayon rainbow homage. To be an Emily, all you need are bright, vibrating lines, your vision drawn, as hers was, onto fields of air. Then file out of doors, art in hand, and down the sunny walk. Never mind her vanishing hills, ridge upon ridge green brown to green black to green blue-- or the reverse avalanche of clouds outdistancing the upthrust trunks, the roots’ rock-splitting grip. ii. Monkey Puzzle Tree (Stanley Park, Vancouver, B.C., 2002) Serrated, drooping, with stiff overlapping leaves, each branch makes a ristra of knife- edged, succulent stars. A cactus in the rain forest? One of her cubistic dreams? Its palette spells restriction, a dark, puritanical green, but the underwater sea creature it conjures casts about in wild contortion. Snaking branches, Medusa’s tortured hair. Independent. Don’t touch! No other of its kind on the continent. A loneliness, beloved, she might have said, of the sky. iii. Totem (Tsatsinukwomi Village, 1907) I slept in tents, in roadmakers’ tool sheds, and in Indian houses. I travelled in anything that floated on water or crawled over land. Emily Carr No more the timid student, too shy to view a naked model, you have come up the coast by boat, alone, and are not afraid now to sleep alone in the emptied longhouse. You step gingerly past banana slugs, dodge famished cats that swirl underfoot as you tramp the rotting plank walk out to the edge of the abandoned Indian village. There, through clouds of mosquitoes and stinging nettles higher than your head, you slip, fall before D’Sonoqua, woman of the woods, stare stunned into the wild OO’s of her eyes, the black cavity of her mouth, its breath filling the air between the outstretched arms, the dangling, eagle-headed wooden breasts. Easy sacrifice—if burning skin is all it takes to find her, this towering totem, partner of Raven, figure to warn children against. Witch Woman, hungry, unappeasable, you must capture her before moss and rain reclaim the heavily sculptured torso and the eyes that echo through you until you hear your own fear beating inside her body’s hollow drum. iv. Bole or is it burl? The knot on the trunk, the condensed whorled pattern in the wood. Then the unraveling, the out- reaching. Knot as navel, wrist, magic spot these ribbons extend from. The witch in the wood is breathing, extruding a bouquet of scrawny spruce fingers, a root system grasping for air twenty feet above the ground. v. Sea So this is how forest becomes sea-- a voyage the mind takes, anticipating boundless waves, new islands of light, the brush stirring in its wake the fingers tagging clumsily along. vi. Weather Emily, old girl, you have us bouncing through a whirl- pool you long ago defined. With what relish you frame these tumults of cloud, boiling eddies of sky, thunder we can almost see crumpling the canvas surface. vii. Flesh Tempting to ask why you would have none of it, not Georgia’s flagrant petals or Frida’s florid hearts. Why you favored greens, not reds. Not flesh but the mind home- bound Emily knew was “wider than the sky.” In love with trunks, ferns, bark, and air, high and fathomless-- abrupt maiden, vagabond sister how can we know you except for these coils, spurts, cascades of writhing growth, a raw sexual force your forests understand. viii. Indian Basket Between its earth-red stripes a tawny grass wind blows like currents around a globe in arrows of circulating light. She wants to breathe inside its brittle flexibility, immerse her face in its darkness, leave it out in the rain and inhale the sweetgrass smell. Recalling Sophie, her basket- maker friend, Emily strokes the knobs grass makes crossing over grass, thinks she might dissolve at the edges, the way its curved sides alter the space around it. ix. Potlatch (Victoria, B.C., 2002) Teatime and the Bengal tiger in the Kipling Room at the Empress Hotel still sends its stuffed snarl through sun- slatted afternoons, potted palms and lace. Down the street, past the place of your birth, herons fly from the park where you painted, soar above your “House of All Sorts” in their daily departure for the shore. Today, D’Sonoqua stands display at the Royal Museum. Klee Wyck the Haida name you, “Laughing One.” But by the time you finish your “Potlatch Welcome” the Crown will already have banned the dancers, locked up elders, grandmothers-- the gift of feasting forbidden, the art of gifting abandoned—and all the weave unraveled until Sophie’s twenty babies arrive half-starved and so silent the grave- stone carver, not unkindly, calls her his best customer, helps keep her tab alive so she might place another marker in the village’s overgrown burying ground. x. House/Caravan (1913-1933) Scrub, rearrange, reorder and resign yourself to reduced circumstance. The King’s radio message New Year’s Eve still makes you cry. Crabby tenants. Fix the plumbing, and the heat. In the center of the ceiling paint eagles, still there. Tlingit design. At last, pack your van. Collect your menagerie. How many dogs? Add boxes, sketchpads, your monkey and the rat. Tighten canvas sides. Put the entire household on wheels. Now leave. You’re off! Summer’s woods at last. You’re old enough to bathe naked in the stream. xi. Horizon Rivers of air fill your later canvases. Above the Strait of Juan de Fuca, headlands you climbed to sketch from, your skies unleash reverberating lines. What did you see but magnetism, subatomic timbres, currents you struggled to make visible until the ethereal became too bright to bear and you re-entered shadow and wood. Green drape of cedar. A trunk’s undulating stalk. Regardless of horizon, all is swirling, fierce, boring not down into darkness but through into light. Here: these pulsing trees frame a birth canal into the deeply scarred, deeply scarved dark-- your hand drawing the shawl of the forest, coaxing her to lift her hem and let us in. Terry Bohnhorst Blackhawk NB: Italicized phrases in the poems are taken from Carr's writings. These sequences are from the author's book, Escape Artist (BkMk Press, 2003). Terry Bohnhorst Blackhawk is the founding director (1995-2015) of Detroit's InsideOut Literary Arts Project (www.insideoutdetroit.org) and the author of five full-length volumes of poetry and four chapbooks. Escape Artist (BkMk Press) won the 2003 John Ciardi Poetry Prize, and One Less River (Mayapple Press) was listed as a Top 2019 Indie Poetry Title by Kirkus Reviews. During her years as an educator, Blackhawk enjoyed using ekphrasis with high school and university students through the Detroit Institute of Arts. She writes about ekphrasis here. Teachers & Writers Magazine / Ekphrastic Poetry: Entering and Giving Voice to Works of Art The Kiss Bird in Flight in flight over the tree tops a boisterous chorus-- aubade even when not conducting the wind a raven shapes the twilight sky in flight a single blackbird swallows the day-- nocturne The Dreaming Muse An infinite dream blooms inside the elegant head, at rest on a pedestal. Her eyes close to the noise of the wakened world. Cast in white marble, an ageless patina smooths brow and cheek, carved in the edges of a crescent moon. The air around her shapes itself into clean, linear features⸺an abstraction of woman. One you might know at night; an evocation in the morning. Her mouth is inscrutable. The marble softens at the Cupid’s bow, allowing only the slightest opening of her lips. Come closer and you will feel the cool breath of one descending into the deep end of sleep; into a pool of lassitude. Her dream is sweet, and so magically elsewhere – lapis skies swirling with gold stars both day and night. Exotic forests with sated tigers. Believing this dream will never end, she cannot help but smile. Barbara Sabol Barbara Sabol is a retired speech pathologist attuned to the music and timbre of voices in conversation, and within the lines of a poem. She writes both long-form poetry and haiku. Her fifth collection, core & all: haiku and senryu, was published by Bird Dog Press in 2022. She is the associate editor of Sheila-Na-Gig online, and edited the 2022 anthology, Sharing this Delicate Bread: Selections from Sheila-Na-Gig online. Barbara finds both editing and teaching essential to a sustainable writing life. She lives in Ohio with her husband and two wise old dogs, who listen to every line she writes. The Art in My Nerves, Not on My Tongue She turns to face me but has no words for the question she needs to ask for me to tell her not what she’s staring at but why we’re staring. Why is Cy Twombly the only artist I love whose work I can’t explain? His scribbles certain as de Kooning’s brute slashes, more specific than most of Pollock’s gestures, yet honest as a child’s. My body remembers slipping into a new pair of small sneakers and running fast and hard as possible to the horizon. I can’t explain to a nonbeliever why I can spot a Twombly across a gallery and rush to it when the aesthetic atheist says, “I could do that.” She can’t but how do I know? I lean into the space in front of a Cezanne and luxuriate in the way each small moment on the canvas is complete in itself yet crucial to the full reach of the surface. She loves those moments I’m unleashed by the way paintings look like everything but their flat plane altered by strokes and whacks. She loves that when I eat breakfast on the porch the homes across the modest lake compose a Monet in the last lingering fog, the houses vivid angles over their wobbled reflections. I could ride for hours the sensual curves and fierce colors of Matisse and try not to jump up and down because that makes the gallery guards nervous. I hold none of these higher than the little worlds completed in Rembrandt etchings and sketches. My first time in Montreal, newly off the bus Into the twilight, hungry, my chest opened to strangers who refused to recognize my questions in English. They insisted on incomprehension and I loved them without sharing their convictions, their coarse local French a lunar landscape I fumbled through, being their grateful alien intruder. My love for craft beyond muscle discipline has no apparent margins. Yet like Dubuffet, Twombly revs my nerves into higher gear the way mere scribbles don’t, the way I, the least rebellious student, couldn’t bring myself to do homework even if it was easy though I dreaded the inevitable punishments. And I love unthought scrawls for their eloquence but Twombly writes letters from my home planet, full of news I can’t interpret in a script I recognize but forget how to read. Richard Ryal A poet, professor, and editor, Richard Ryal has worked in marketing and higher education. He stops for no obvious reason sometimes and no one can talk him out of that. His recent publications include Notre Dame Review, Sheila-Na-Gig, and The South Florida Poetry Journal. The Wilton Diptych What was it about that small, paneled painting on wood, hinged like a box and kept quiet for centuries? Was it the wonder of its preservation for six hundred years, so fresh that the colors still glow as though molten-- lazuli, gold, vermillion? What were you seeing there, mother, now seven years gone, when you went to look at it year after year, so struck it stayed with you even when you’d lost yourself? You guided me through it as I held the picture over your hospital bed, though your mouth slurred to one side, and you could not lift your head. See that blue, gold so godly they could make a king kneel? There he is, Richard II, on the left inner panel, his blush still uncracked, as three saints present him to the facing heavens. See how the saints’ hands incline toward his head, as a mother might guide a child new to walking. For awhile, you could still speak of craft, innovations in paint, in proportion. Respite from thought loops that troubled you, your pleas to be walked out of there, back into a life once lavish with pigment, divinity you could believe in. On the right side, the angels in unfaded blues crowd around the virgin and child. They look drugged with color as they bless England, hold up her streaming pennant. Everything’s moving and everything’s still. The infant Christ, here, will never grow up, never suffer, suspended. Angels’ angular wings at the back of the scene curtain off the world of immortals. Was it the sense of a shuttered past swung open, still vibrant, unveiling itself? Was it the mystery of the work’s unknown maker, like you, now, a closed box, unanswering? There’s a gap in the wings right above Mary’s head. Mom, what did you know about that? Or about the strange way she holds the child’s foot, her fingers encircling it in a perfect O, tipping the tiny thing up so its sole faces us, as if to say: here it is, always here, the untouched, in its untrodden softness-- might this be miracle enough? Clara McLean Clara McLean lives and teaches in the San Francisco Bay Area. Earlier poems have appeared in Rattle, Cider Press Review, Terrain.org, Foglifter, West Trestle Review, and Berkeley Poetry Review, among other publications. Carved on the Lintel: The Temptation of Eve originally on the Cathedral of St. Lazare, Autun, France Buccaneer of flux, she floats above a door, a long sine wave—flagship of goodbye. Her eyes, grapes, are not yet pressed. Eve’s face shares my father’s lids and parenthetical brows. I view her through his quizzical eye. Modeled in a province of wine, Eve blooms sober-cheeked. Soft pulp does not keep. She cradles her chin. An out-sized hand insinuates, “Seize the day.” Sighing like her mother, old enough to know the value of let go, I disobey idle desires. Where did I ditch my bad-girl smarts? Goddess, caught mid pluck, you dare. You bet your life. Yes, you pay—that itchy leaf monokini and hard-knock knee-- but still wager Paradise with me. Marion Brown A Yonkers, NY resident, Marion Brown holds a B.A. from Mount Holyoke College and Ph.D. from Columbia University. Finishing Line Press published her chapbooks Tasted and The Morning After Summer. Her poem “In the Dock, Fagin Reflects” won the Portico Poetry Competition. Other poems have appeared in Guesthouse, the Women’s Review of Books, Kestrel, The Night Heron Barks, and DIAGRAM. She serves on the Advisory Committee of Slapering Hol Press and National Council of Graywolf Press. Her website is at marionbrownpoet.com. Chez Isabella, ca. 1990 “In March 1990, the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum in Boston, Massachusetts was robbed by two unknown men. The thieves removed works of art whose value has been estimated as high as $500 million.” —FBI website Sleepless nights are a malady that, for me, meander back in time over fifty years, all the way to my early twenties; but there are advantages to being awake in the long, dark, blue hours when quiet finally descends. Tonight, or rather this morning, with the news of Walter’s unexpected death earlier yesterday, and at this time of year too (late March), I’m grateful to be awake, suddenly recovering and unraveling memories from thirty years ago…. Walter was among the four of us who came together after the robbery, united in our grief. The museum had always felt like a second home to some of us, a home that is actually a palace, but a home nevertheless. The place is not very big as museums go, and so most of us who worked the day shift knew one another. I was the one of the four of us who had been there the longest; I was twenty-six when I started and forty-seven at the time of the heist, which is still the largest in history: how time passes! Walter was hired the year after me, and so he and I went way back. We used to joke that we were the lifers, since most of the museum’s guards didn’t last long. The pay was so low ($7.35 an hour in 1990), but money was not the main reason we were there. Walter had become friendly with Jason a few months before the heist; I think Walter had a little crush on Jason, truth be told. It was a bit sad to me though, not only because Walter was about twenty-five years older than Jason, but also because Jason was clearly straight. At first, our meetings consisted of just the two men and me. While all of us knew or had at least met Melissa, none of us liked her initially; we all thought that she was a spoiled brat, and pretentious, too—affecting a British accent the way Madonna used to do. She had been scheduled to work that morning after the robbery, and word got around that when Melissa arrived at the museum and saw the place surrounded by police, FBI, and yards of yellow crime tape, and then heard what had happened, she burst into tears. Eventually, she somehow learned about our get-togethers and asked if she could join us; and because we were so moved by how bereft she still was, we let her into the group. The heist was all we could talk about for the longest time; we needed to debrief. Though almost immediately, we were instructed not to discuss it while on duty, whether among ourselves or with visitors; but in the early days, the robbery was just about the only thing most visitors wanted to talk about, especially because the spaces where the stolen paintings had been were left empty, a haunting reminder of their absence. We were also discouraged from talking to the media. Some of us watched as we were portrayed by actors on TV’s America’s Most Wanted! It was a heady time. We couldn’t bear the thought of the thieves having full run of the galleries for over an hour, pillaging, while the two guards sat bound and gagged in the basement. Of course, the four of us speculated about the perpetrators, and just to get this out of the way—none of us knew or had ever even worked with either of the two guards on duty that night, since we had always worked only the day shift. But Walter and I didn’t think it was an inside job. The only one of us who had lived in Boston all his life, Walter was convinced that Whitey Bulger had something to do with it. And though I had seen the names of several infamous art thieves bandied about, I remained uncertain. Jason was mostly interested in ongoing theories involving one or both of the guards on duty that night, and/or the IRA, whereas all Melissa would say was that she “hadn’t a clue.” We also talked about the stolen art, of course. And about the violence of the steal—paintings cut from their stretchers, stitches of canvas and flakes of paint left on the cold, tile floor. Melissa visibly shivered and said that it was as if she could feel the razor blade pierce her skin as she imagined the canvases being desecrated. But when we asked which of the stolen works meant the most to her, she grew somewhat stony and replied, simply, “All of it.” Whereas Walter, Jason, and I definitely had our favourites. For Walter, it was the Manet, Chez Tortoni (ca. 1875) which depicts a mustachioed man in a top hat writing in a café; he looks straight out at the viewer with a black, impenetrable gaze, a glass of something amber by his writing hand. When we asked Walter why that one, he said that he had always identified with the man, that he himself often wrote in cafés; Walter fancied himself a writer and, to his credit, he had had pieces published in local periodicals. He added that whenever he walked by Chez Tortoni while on duty, he always experienced a certain frisson of recognition. And there actually was a resemblance: Walter was tall, thin, and somewhat pinched, though he didn’t have a mustache. Jason couldn’t wait for his turn, he even spoke over the last few words of Walter’s. “The Rembrandt,” Jason announced. “The Storm on the Sea of Galilee (1633), his only seascape.” Jason said that he had always liked the “movement and the muscularity” of the painting, and also that it reminded him of a good action movie (I should add that Jason was only twenty-three at the time, just out of college, idealistic and naïve, an art history major taking a year off before starting graduate school.) He also liked, Jason went on, the fact that Rembrandt had included a self-portrait in the painting. And Jason actually had us laughing too, “about the guy in red, just to the right of Rembrandt, who looks like he’s hurling over the side of the boat.” I was next, and it was easy because I had felt the same way for a long time: “The Concert” (ca. 1664), I said. “One of only thirty-six surviving works by Vermeer.” “Because?” Jason wanted to know. “Because—well, first of all, my husband Philip is the first violinist in a chamber music ensemble.” I focused on Jason and Melissa as I said this, since it was old news to Walter. “But it’s more than that, too.” The three of them were staring at me, waiting. I thought about how often visitors to the museum had told me they heard music when they looked at the painting, whereas I had always only heard silence, and I loved that, so I said it aloud: “The painting is called The Concert, but I think it’s before the concert.” I cleared my throat. “The painting is so calm and balanced, and as always with Vermeer, there’s that extraordinary quality of light.” We were in a café on Beacon Hill at the time, and as I was speaking I suddenly pictured our quartet from afar, gathered around the table in a pool of light—as if in a Vermeer painting. Of course, the four of us got to know each other somewhat during those meetings, too. Melissa had grown up on the Connecticut coast (primarily New London), the only child of wealthy parents, but when her parents divorced (Melissa was in her teens then), she and her mother had gone through some hard times. “Anne, you actually remind me of my mother,” Melissa said. I assumed this was a compliment, or that was how I took it anyway, and so I thanked her. Three years younger than Jason, I think Melissa was still finding herself, thus the intermittent faux British accent. Whereas Jason was Jason, an outsized personality writ large, and because of that we all felt like we already knew him. We had met his girlfriend Sarah, too, and heard about their dog Vans (a play on Dutch painters and a brand of sneakers Jason favoured), and also about their fights over having children: Jason wanted them, but Sarah didn’t. I’d be very surprised if Jason and Sarah are still together. Walter, the oldest among us, somewhere in his late forties at the time (he would never say), was also the most circumspect. Perhaps this was because he was gay and of a certain generation? He said that he lived alone in an apartment in Back Bay, that he had a handsome tuxedo cat named Butley who he imagined as his butler, and that he liked to think of himself as a writer; but that was the extent of it. Our friendship, Walter’s and mine, was never personal; our conversations were mostly about the arts. I told Melissa and Jason what Walter already knew: that Philip and I were childhood sweethearts, that we had been married for almost twenty-five years, that we were childless by choice (Jason glowered upon hearing this), and that in addition to Philip’s involvement with the chamber music ensemble, he worked for the Post Office. “Ours is a miniature life,” I said aloud, surprising myself, “and we like it that way.” Those get-togethers became more sporadic and began to taper off during that winter, just as the case itself grew cold; and by the following spring we had stopped meeting altogether. Jason was the one to leave the job first, no surprise; I think it was within a year or so after the heist. Melissa stayed on for several more years, before quitting to follow the man who became her first husband across the country to California. That left Walter and me, the lifers, until both of us retired at around the same time approximately ten years ago. And now, poor Walter is dead. Philip (no longer the first violinist) had a performance earlier this evening and so, though I’m sad, we had to go. Afterward, we went out for a drink and toasted Walter, and I couldn’t help but think of Chez Tortoni. Back home, as I stood in front of the bathroom mirror applying cold cream to my face, a lifelong ritual, I just happened to see the clock out of the corner of my eye: it was after one in the morning, the time of the robbery. As I slowly wiped the cleanser over my face and examined the crows feet, and the marionette lines around my mouth, I thought about the effects of time, and of the lines as cracks in my façade; and then I thought about the tiny pieces of the paintings as they lay on the museum floor. Looking back on the moment of the heist from this sleepless night in my seventy-seventh year, I realize that I was still young then. Now Walter’s gone, and I haven’t a clue about Jason or his whereabouts, but I did hear from Melissa not long ago; her mother had died recently, and she said she thought of me. She’s back in Connecticut, divorced, remarried, and she has a daughter. Meanwhile, the stolen art has never been recovered. Robin Lippincott Robin Lippincott: "I have published six books, most recently Blue Territory: A Meditation on the Life and Art of Joan Mitchell. My novel Our Arcadia was likened to a pointillist painting. For ten years I reviewed mostly art and photography books for The New York Times Book Review. I teach in the MFA Program of the Naslund-Mann Graduate School of Writing at Spalding University, and live in the Boston area." |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|