|

Guest editor's note: Thanks to everyone who submitted a response to the Jenn Zed “Louisiana Zombie Afternoon” Challenge. It was a pleasure and an honour to be entrusted with your new brain droppings, fellow ekphrastic citizens. I am especially proud to have helped provoke such a wide range of content, both in style and substance. A huge thanks to the editor-in-chief for entrusting me with her baby, and allowing me to spread the word of Zed—a prolific, and phenomenal, contemporary visual artist worth following to see where her muses pull her next. By the way, see if you can spot the tricky fiction masquerading as a poem. And with that, I present you The Prose: Jordan Trethewey ** The Calm at Pool Parties The day the hospital orderly wheeled her daughter, Ella, in for an emergency surgery, Nora received a text message from Rashid. "Getting married," it said. The gaping hole in Ella’s knee distracted her. How could a pool party go so disastrously wrong, thought Nora. According to the birthday girl’s father, a boy had pushed Ella during a game to hurl her into the water, only her knee wedged into the raised edge of the pool and her head hit the water instead, leaving half her body outside. She couldn’t break her fall. Her knee was mangled: battered raw flesh peeked out from a hole, white dots of cartilage in the mix, entrails of blood lingered at the bottom left. For some reason, Ella didn’t complain of pain and the bleeding was minimal too. Nora was quiet as she realized that things could’ve been worse. She watched Ella sitting in her wheelchair calmly listening to the doctor as he explained what he will be doing during the suturing process. Watching, she realised that for some strange reason, she too hadn’t complained about pain, blood and holes either. In the cold corridor waiting for the doctor to finish, Nora thought about the days when she was the queen of pool parties. At one party, she had met a boy — a friend of the birthday girl’s brother. She was probably about twelve that year, he was definitely older, taller with broad shoulders, and he swam for the school team. His breath smelled of soured beer and cigarettes as he tried to kiss her behind the bushes. He didn’t push her the way Ella was pushed. But he did try to do something else. The one thing that stopped him from going further was the dog barking at them from the edge of the bushes. The pool was a temporary pool, one that stood on a stand rather than built into the ground. He had taken her hand and led her calmly to the back of the pool where the hedges hid the fence from view. When the dog barked, he leapt up and ran off, leaving her there with her bikini bottom half way down. Nora never saw the swimmer again. She made a mental note to tell Ella never to follow a strange boy into the bushes. At another party, the party that Kate McKenzie threw for her fourteenth, they saw the floating carcasses of the family’s pets just before everyone jumped into the pool. The family chinchillas had flung themselves into the water. They looked like furry ear muffs that you’d wear when skiing, bedraggled and wet from being splashed with soft snow. The party had just begun too. Mrs. Norton had just arrived with Stephanie. She gagged and turned around, dragging Stephanie with her, sobbing uncontrollably. The scene reminded Mrs. Norton of the day they had found her two-year-old brother, Tommy, face down in the pool, Stephanie told Nora later. Kate was too distressed to continue the party, so everyone was sent home with a slice of cake, birthday song unsung. Stephanie never went to another pool party. Nora made a mental note to remind Ella that drowning is always a possibility when there is a pool in your backyard. As Nora and her friends grew older, cool drinks were surreptitiously introduced. Some kids arrived with flasks that were filled with iced soda; nobody asked what kind. During those pool party days, the adults were usually having pool parties of their own or were playing a round of eighteen holes. Once, one of the boys had too much soda and started to dance naked on the table. The security guards were called, they threw a towel over his head and took the boy away handcuffed. His folks had to bail him out later; he was charged for indecent exposure. They were all sixteen and celebrating the end of their exams and their imminent departure from Dubai. Everyone went to different colleges after and she never saw the boy again. Nora made a mental note to remind Ella that alcohol at pool parties is a mistake. Nora would remember Eliza’s pool party most. It was the year everyone turned eighteen and were high on gin tonics. She and Rashid were an item that year and they had decided that eighteen was a good age to commit. As they each took off their bottom halves, fumbling and giggling on the black and white tiles, Nora wondered if the bathroom was a romantic place to lose her virginity. After, Rashid denied that the child was his. Nora made a mental note of reminding Ella that unprotected sex at eighteen has consequences. Days after the suturing, Nora walked calmly into Accident and Emergency, asking to see the Resident who had sutured Ella’s knee. In the consulting room, she told him that she needed suturing too as she held a gun to his temple. She calmly unbuttoned her blouse and unhooked her bra with her free hand, then turned the gun on herself, pointing the nozzle at her heart. The Resident, handsome and collected, the doppelgänger of Rashid, calmly asked her to put her clothes back on and scribbled into his medical notes. Eva Wong Nava Eva Wong Nava lives between two worlds (literally and physically), and writes to save herself and the world. Her flash fiction appears in several places and she was nominated for the Pushcart Prize once. She is also an award-winning children's book author and an avid collector of children's picture books. ** No French Quarter For Your Thoughts The corner of Bienville and Bourbon streets, friday night at 10 o’clock: smoke and mirrors at every turn. Partiers hanging on delicate wrought iron balconies, still standing, they moan under the weight of hurricanes and beads tossed to the street. I got beads of every colour while stumbling through the mass of revelers in feather masks and painted faces. In New Orleans everyone meets your eye. Hey Pretty Baby! Have some Southern Comfort with your Hurricane. Show us your tits baby, its okay. We got your pretty beads. Don’t wear ‘em downtown, though sugar, the muggers want your shiny tourist stuff. I forgot Southern Comfort is liquor as I went looking for the underbelly of New Orleans. I found no such thing or maybe I didn’t notice. I visited the House of Voodoo, could have been the House of Pancakes. I passed a few gothed-out Pentagram sporting kids but they just wanted to bum a smoke and read my Tarot Cards. On Toulouse, I noticed the most beautiful boy dancing outside of the Spotted Pig. Eyes closed, he undulated and vibrated heat. We had a moment of blissful eye contact before he went searching for the next good tune. I walked along Jackson Square and sauntered in the alley where Brad Pitt and Tom Cruise made vampires sexy. I sent my vibes out to the immortals. Come and get me! But my call went unanswered amidst the swirl of tempestuous confusion, the cacophony of drums, horns, and electric guitars blaring from every bar, and the mist filled with souls getting high on fumes and spills. Liz Axelrod Liz Axelrod received her MFA from the New School in 2013. Her work has been published in Yes Poetry, The Rumpus, The Brooklyn Rail, Electric Literature, The Ampersand Review, Wicked Alice by Dancing Girl Press, Counterpunch.com and more. Her chapbook, Go Ask Alice (June 2016) was chosen as a finalist in the Finishing Line Press New Woman's Voices Competition. Liz is an Adjunct English Professor at SUNY Westchester Community College and NYC City Tech. She has reviewed books for PW, Kirkus Reviews and Lunalunamag.com, and was founder, co-host and curator of the Cedarmere Reading Series in the home of William Cullen Bryant (2014-2018). Liz now resides in sunny Albuquerque, NM where she is finding her place in the Land of Enchantment. ** Child From a Pipe Her consciousness opened up gradually, and at first all she could understand was the darkness. As the unending seconds finally expired and gave way to one another the all-enclosing nothingness gave form to a muted warmth, an orange glow. She felt herself suspended in the weightlessness, her skin compressed in the heavy, viscous fluid. Her body screamed to move, to disentangle her from the suffocation the ether aroused.Yet her limbs would not rise, her head would not tilt upwards. Her thoughts could not detect the tentative connection it should have had with her movements. It was as if a barricade had been erected at her brain stem, arresting her control, turning mere discomfort into panicked frustration. Outside the pipe the doctors congratulated themselves. Subject #26 had maintained life for the past five minutes. The previous record had been two. Gatson was the one to notice a sudden spike in her heart rate. Their adrenal monitor revealed a sudden surge of the hormone into the bloodstream. One segment of the team moved to add tranquilizers to the transfusion fluid while another moved to attach intravenous tubes to her index fingers. It was all for nothing. The shock from the hastily applied anesthetics may have been the culprit, or it could have been an unseen component all together. In any case, Subject #26 expired. Preparations were made to begin tests on Subject #27. Joseph Paoli A senior at Trinity Preparatory School in Winter Park, Florida. ** The Omega Woman We wake up in the No-More-Chance Motel. "I came here from a future time," she'd said, the night before. "I had a message... don't know what it was." No Staff. We scavenge in the breakfast bar. A zombie lurches through the kitchen door. "They built me from technology," she says—I am too busy with the axe-- "but I eat much the same as you." And. That. Was. Much. Too. Close. Now, how to improvise coffee…? "It's strange how similar our peoples are..." She has this curl of hair behind one ear. "If we get close, you might become like me." Four in the foyer. Pump-action. Easy. I need more shells. "They spread by something in the blood, you know?" A sound outside? "And I am blood-borne also, in a sense..." Shit, that's a lot of zeds! Turn back. This service door swarming with zombies too --how is it with life on the line I feel? Only one way to do this. There will be gore! "Don't get it in your eyes," she shouts. No good. Retreat. We barricade the door. Upstairs I sponge the blood away with care. "Oh wow!" She seems surprised. "I’m capable of love...” Her eye's have tiny little lights, something rotating deep inside. We kiss for quite a while. I never had my fingers in a cyborg girl before. "No time," she gasps, and starts to glow. I've always been a silhouette against the light. "I have the message now: Brace yourself, this stings." Ian Badcoe Ian Badcoe lives in Sheffield, England, where he is a software developer and local poet. He has aspirations to being a non-local poet but hasn't yet been able to get enough "quantum" into his work. ** The Underlings 1. You, this side of my threshold. I thought you were gone for good. I have a premonition already. The weight of the risk, the storm that is coming. Still, I fling the door open to an old friend. It's not even a question. 2. The equilibrium of the world shifts. The electricity changes. Possibility and potential are two of a thousand sparks. Everything is illuminated. 3. I'm diving in, I'm saying yes to whatever transpires. I am astonished anew. I am renewed. I am walking right out onto those waves in instant, unwavering faith. My joy is so profound that I'm a spinning top, a whirling dervish undone at the seams, pure flow. The Game is alive, magic is afoot. 4. Of course a warning shot was fired. While casually inhaling down one of those Dunhills I no longer smoke, I fired it myself. 5. Of course I've tried to find you. Since all this has happened. Of course you'll see this one day and know I'm still writing poetry about you after all this time. Never had anything to hide from you, and never will. Yes, I am writing my heart out after you. Of course I am. 6. If I wanted more than you were offering, it was still the bare minimum that I asked. Just the basics. 7. Still, don't think I only blame you for the fault in our stars. I was the bad seed. I was the wild heart, I was the tempest. 8. We are standing on the pier, and the sky is falling. The lake is bigger than the sea. We are closer than we have ever been, and it is almost over. 9. I will never let you fall, you say, when I tell you I am falling. I will never leave you nor forsake, you tell me, while you tell me you are leaving. It is something I have heard somewhere before. Lorette C. Luzajic Lorette C. Luzajic's poetry has appeared in hundreds of print and online publications, including an assortment of anthologies, and journals like Rattle, Grain, Pacific Poetry, and (forthcoming) L. A. Cultural Weekly. She is also an award winning mixed media visual artist whose imagery is heavily dependent on concepts in poetry, with work shown all over the world, from Scotland to the Yucatan to North Africa. She is the founding editor of The Ekphrastic Review. ** The Find The girl found him on the edge of the schoolyard. His dirty Nikes jutted onto the mowed lawn from the switch grass and wildflowers, his bare legs dappled with shadows of Queen Anne’s lace. She parted the blades and stems like curtains, thinking he was asleep and she should wake him. But he didn't move, his thin body centered on a blanket patterned with kittens and puppies. His left arm cut across his tie-dyed T-shirt while his right twisted sideways, smooth and hairless in the morning sun. The girl knelt and stared at the explosion of skin and bones that had become his face, his hair stiff with blood that had oozed onto his pillow. She touched his leg and his arm and tried to peel his rubbery fingers from the pearlescent handle of a gun. Covering her face, she curled up near the boy’s feet, listening to the echoes of her classmates playing four square on the asphalt. ^^^ He came up missing again, the neighbors whispered. His mom called the police last night. People worried but not too much. Just a week ago the police had searched for the same 14-year-old boy who wandered away in a T-shirt and khaki shorts. He's like that, they said. It’s nothing new. Sipping coffee, they recalled the sidewalk battles between mother and son and the shrieks that pierced the soft air. Seated by their bay windows, the neighbors viewed the kicking and clawing as the boy struggled to break from his mother’s embrace. That family, they said. They’re really something. Neighbors sighed. They shook their heads. Turning away, they pictured his mother’s silhouette as he escaped to burrow into the wall of tall grass that bordered the school. ^^^ He'll turn up, they said. The police will find him. He's probably just hiding again. That morning, parents heard the AMBER Alert as they walked their kids to school. Checking their phones, they saw his name and photo, and imagined his daily race to vanish. A few thought of his mother and how she found his empty rumpled bed and the window that opened onto the twilight. A sketch book and markers were strewn across his braided rug, the pages filled with vivid outlines of children with cigarettes and guns dangling at their sides. Her purse was upended in the corner, the contents spilling beyond the snaps and zippers. Picking it up, it felt lighter, her handgun missing from the deep center pocket. ^^^ As parents and neighbors waited for news, children sat in classrooms, waiting for recess. When the bell rang, the girl was the first to bolt out the double doors. Running in her long grey dress, her head scarf rippled as she went beyond the swings and climbing toys to find her place near the grass and weeds. She's weird, kids said. She wears ugly clothes and smells like icky spices. No one likes her. Parents told their kids not to tease her, but didn’t understand her olive brown skin, or her slim quiet parents dressed in loose, woven clothes. They thought of her standing apart at school events, or of her absence at soccer games or parties. When they heard she had found the boy, they wondered how long she had sat there, or even if she screamed. I know my kid would have told someone right away, they said. I wonder if she did. As they heard more, they ignored how their kids had jeered when the girl came back, trying to tell them what she had found. Go away, a boy said. Yeah. You can’t play with us, another sneered. You’re not American. When the girl sobbed, the kids yanked off her scarf and pushed her down. You’re lying, a girl said. You just want to trick us, a boy taunted. I bet you got a bomb under that dress. Kicking stones and pulling at her clothes, the children scattered when teachers came, becoming quiet and pale when they saw the girl had told the truth. That poor boy, their parents said. And that girl, they added. But the more they learned, the more they turned inward, thankful it wasn’t their child or a close family friend, finding comfort instead by sending their thoughts and prayers. Ann Kammerer Ann Kammerer lives in East Lansing, Michigan, where she works as a copy and feature writer for small business and higher education. Her short fiction has appeared in several regional publications and magazines, and has been awarded top honours in fiction writing contests.

4 Comments

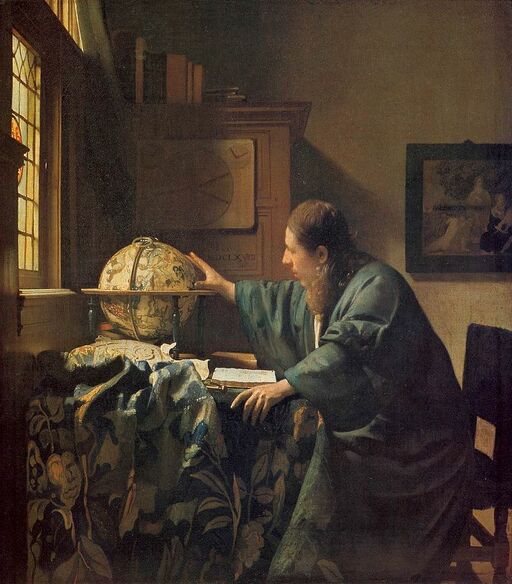

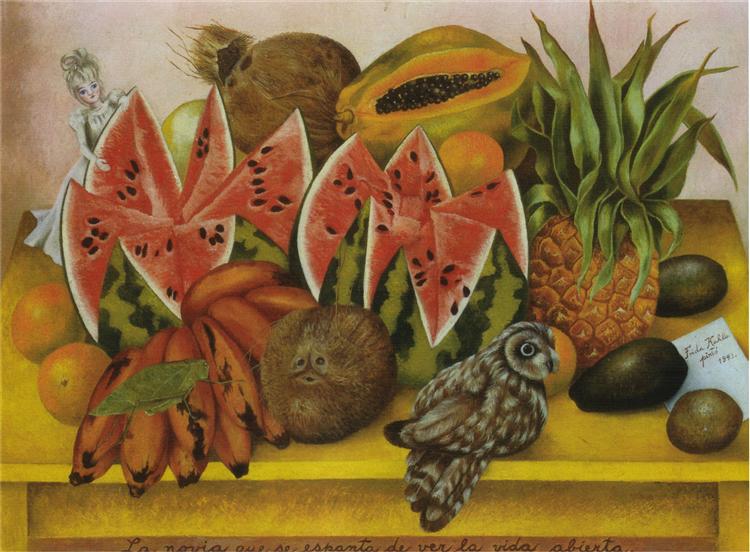

Waiting for Gabriel “One tries to cure the signs of growth, to exorcise them, as if they were devils, whenreally they might be angels of annunciation.” Anne Morrow Lindbergh, Gifts from the Sea Each morning leaving their cells and each evening returning to them, the monks of the Cloister at San Marco made a small pilgrimage to the Annunciation. The cloister’s monk-artist-in-residence, Fra Angelico, painted his fresco of the mystery-charged encounter between woman and divine messenger at the top of the stairway leading from the small refectory to the second floor corridors of cells. Ascending to the scene five hundred years later, I pondered several things in my heart. Because the fresco throbbed with detail, because the soles of my feet felt the tickle of the feathery leaves in the walled garden where I could have been standing just outside the portico of their tete a tete, and because I saw the mixture of solemnity and curiosity in Mary’s tucked chin and lifted eyes, I wondered what it would be like to be a woman approached by an angel on a day when all the ordinary things go on as usual--the sun popping over the horizon and the little red and white flowers opening their faces to it--yet everything is altered forever by the entrance of the winged one, the dark rainbow bands of indigo, scarlet and saffron fluttering behind him nothing to the words he has released into the room. And I wondered about the monks who passed this moment each day on their ways to meals and prayers for four hundred years. How would it shape one’s daily life to live in the midst of such a moment? I almost wrote “a frozen moment,” but there is nothing cold or rigid in their poses, not in the angel’s bow of reverence or in Mary’s echo of that bow, her cloak still fluttering at the hem from the wind of his wings, her wrists and his crossed before their torsos like wings at rest. What might seem possible in this life if I were reminded of that moment as frequently as I am, say, of supersized burgers and Toyotas by the billboards I encounter on my daily rounds? Fra Angelico also painted a smaller fresco for each monk’s cell: another Annunciation, a Nativity, the Transfiguration, and other scenes from Christ’s life, along with a host of Crucifixions (these in the novice’s cells) and several Resurrection vignettes, including a touching rendezvous between Christ and Mary Magdalene outside the tomb, the Noli me tangere. Angelico intended his paintings to be instructional devices and regarded himself as a humble tool in God’s hand. While his artist peers adorned the ceilings and walls of great cathedrals where thousands would admire their work, ballasting their reputations, this monk preferred to work within the narrow enclosures of his monastery. How could I not believe in that humility, knowing that he painted each of these smaller frescoes for a primary audience of one—whatever monk occupied the cell in which it breathed its colours? And standing alone in the doorway of each cell, how could I fail to be moved by his beautiful industry, not take it personally? How could I not allow myself to be worked over? I liked imagining Angelico going about his day’s work--preparing the plaster and mixing the colours from powdered earth pigments each morning, instructing his helpers. Each day he would work in one small section of the fresco, covering only that area with the plaster. This area was the giornato, the day’s allotment of plaster, for in creating frescoes the paint is applied onto wet plaster and becomes one with it, much the same way that our lives and souls become inseparable from what we paint onto the surface of our days. Visiting the cells, I wondered how differently one might face each day if one awoke to Mary Magdalene reaching out to the risen Christ as opposed to waking beneath Christ’s limp body hanging from the cross, rivulets of blood still flowing from it. How was it decided who slept where? The novices’ cells were all Crucifixions. Even walking down that corridor was painful; how was it for them, I wondered, young and away from home for the first time, to room with such suffering? It almost seemed a kind of hazing. Perhaps, however, they were given the Crucifix as their nightly companion as a mercy--a way of reminding them that there is greater suffering beyond homesickness and lonely nights, that pain such as theirs leads to redemption. Perhaps daily commerce with that image allowed them to begin to consider pain—their own and others’--a lingua franca. But what about the others? Did they sleep their entire lives following their novitiate under a single image? Did the monks ever vie for a particular cell? Did they rotate? Did they dare to allow themselves to covet their neighbour’s quarters? Were particular images selected for certain monks because of some attribute of faith it was deemed they needed to cultivate? Or was it simply a matter of what cell was available when it was time for a novice to evacuate what I called the Corridor of Crucifixions? Even though this had been all-male territory and no one lived there anymore, I found myself picking out the cell I would have chosen if choice had been allowed, an exercise in imagination like the ones my sisters and I had reveled in whenever our family went house hunting. Each house became our own as soon as we walked inside, my sisters and I racing past the living room and kitchen to find “our” bedrooms and imagining the new lives these new rooms would engender. Was it like that for the monks? Did they imaginatively insert themselves into the rooms within rooms of these frescoes, see themselves transforming in their presence? Cell three would have been my choice, the one with Angelico’s most minimalist Annunciation, far simpler than the more public one in the hallway. A waif-like Mary kneels in a room that is bare but for the compassionate-looking angel facing her. Both figures cross their arms before their hearts, as if to contain both fear and wonder. At least it was the cell I would have chosen for that moment in my life. Having recently felt compelled to worship in a Christian church after a twenty-year sabbatical from Christianity, my heart had fluttered with the same confusion I read now on Mary’s face. I too was bewildered by what had seemed a calling. * * * There must be hundreds of Annunciations in Florence. I counted four by Fra Angelico in the Cloister of San Marco alone. I knew I couldn’t come close to seeing them all, yet each day I trooped out to at least one church or museum, pockets jingling with 500-lire coins for the vending machines that let there be light on the paintings. I saw Annunciations by Martini, Botticelli, Donatello, Ghirlandaio, Fiorentino, del Sarto, Baldovinetti, Leonardo, and da Forli. Each time I approached one, my spirit hushed. In my mind I heard the lines from my favourite Christmas carol, “O Holy Night”: “Fall on your knees./O hear the angel voices.” If I could make my soul quiet enough, I thought, would I hear the words quivering in the gold-leafed air between the figures, perhaps hear beneath them Mary’s heart beating as swiftly as a dove’s? Each day over the last five hundred years, despite whatever horrible things human beings were doing to one another all over the surface of our planet, here in Florence the angel Gabriel has been whispering words of hope to Mary, imploring her participation in a miracle of redemption. And she has been pondering, answering, assenting. Regardless of what has gone on outside each painting’s perimeters, horrors too often sanctioned or even sponsored by the Church that had commissioned many of these works, a contract was being made between the human and the divine. However much ugliness there was in the world, in hundreds of squares of light an angel’s wings settled their rainbows into stillness and an invitation was dropped to the earth. While I had walked among Angelico’s frescoes, my friend Martha had attended Mass in the church of San Marco. I checked my watch and realized that it was almost time to meet her in the cloister garden downstairs. In the hour we had been apart, I had been living in what I imagined eternal time to be like. So focused had been my attention on these corridors, the frescoes, and the questions they raised, that everything else had become blurred, suspended in time. I rushed down the tiled stairway, turning to look up one last time at the angel and virgin who lived always in that stillness. Walking out into the cloister, I felt the cool sunlight of early spring brushing my cheek. Here I was, alive in Florence, in Angelico’s world, in Mary’s world. The sun had not yet climbed the cloister walls when I had arrived. Now it was an hour higher in the sky, and through the clouds it directed a beacon onto a calla lily whose one white ear filled with light. * * * As a girl I liked to play in the two adjoining vacant lots down the street. They comprised the last remaining wildness in our housing development, a place where tall weeds, craggy trees, and bare dirt reigned. Our parents discouraged us from going there, which lent it the allure of the forbidden. An aura of danger lurked there as well because of stories we had heard concerning the neighbourhood bully Buddy Joe who, it was rumoured, tied kids to trees there and burned them with flaming sticks. Occasionally, when there was no one to play with and I could muster the courage, I went there alone. I didn’t know the word pilgrimage then, but I remember feeling something of that anticipation and sense of intention as I entered the shaded path between old elms and hickories. Not that I expected a revelation from God. A simple hello from the squirrel freezing on a branch overhead was all I hoped for. I wanted to be recognized by the birds, squirrels, and rabbits as somebody special, a kindred spirit, one who would understand them if they spoke to her. Was that what appealed to me in those paintings? Was I seeking a vicarious thrill by way of Mary’s selection by the divine? Had I always secretly waited to be surprised one morning by an angel in my living room? Well, why not? Girls are raised on stories of being chosen. Princes, angels—what’s the difference? One tale ends in Heaven, the other in its fairy tale equivalent, the palace. Teenage girls of my generation were forbidden to call boys, or at least strongly coached against being the pursuers. It was our lot to learn the subtler methods of pursuit, most of which involved making ourselves as attractive as possible and putting ourselves in the way of whatever boy we chose to be chosen by. I have blamed fairy tales and the culture they both reflect and perpetuate for our dependence on men, especially as adolescents and young women. But now I wonder if some part of me—the girl waiting for recognition from her furred and feathered friends—wasn’t waiting for Gabriel and settled for being chosen by mortal men. I have been in love with being chosen, perhaps more than I ever have been with any of the men who chose me. So is it any wonder that Gabriel’s “Blessed art thou among women” would hit me where I live? When I had imagined returning to the Christian fold, a major stumbling block had been that I didn’t feel the kinship with Christ as God in human form that I felt that I should. Like most girls who were serious readers, I had spent my childhood and adolescence imagining myself into the role of the male protagonists of the novels I read, trying to ignore the fact that I didn’t think, act, or look like them, trying, like Cinderella’s stepsisters, to force a fit by cutting off the psychic equivalent of a toe or a heel. One of the reasons I had left the church in my twenties was that I simply couldn’t do that anymore. Now, however, I thought about the monks passing by the Annunciation each day, pondering the pact that God made with humanity, that God attempts to make each day with each of us. The human representative in this scene is Mary. So weren’t the monks busy imagining themselves across gender lines, too? Perhaps that is why I respond so warmly to the Annunciation. Mary is the universal human in that moment. She is Everyman as woman. I have been angry with God at one or two devastating junctures. If God is so good, I thought, why doesn’t He come and save us when we need it? How could God have allowed the Holocaust, not to mention the myriad demented ways we torture one another each day? How could God allow earthquakes that take thousands of innocent lives or even my toddler son’s eye injury? I have been offered the weak tea of theological explanations. In times of crisis and in pain’s aftermath, they have seemed flimsy excuses indeed. But looking at Angelico’s Annunciations, trying to read the struggle and joy in Mary’s face was turning my heart. Each morning, through these frescoes, mystery and divine love are whispered into the world and humanity has been given its chance to say yes. Perhaps it isn’t God who has failed us, I thought, but we--God’s hearts and hands--who have failed to bring Her fully into the world, to pull God through our very cells, to suffer and strain and bring forth the good, to fully participate in the ongoing miracle of creation by whatever means we possess. Such were my thoughts after viewing Angelico’s revelations in clay and pigment. I liked thinking that, despite my life in the world, I was perhaps thinking thoughts similar to those of the long dead monks as they viewed his Annunciation—that each day, like they, I am called to be a gateway for the arrival of the sacred in our world. In The Quotidian Mysteries: Laundry, Liturgy and Women’s Work, Kathleen Norris quotes Simone Weil: The effective part of [our] will is not effort, which is directed toward the future. It is consent; it is the ‘yes’ of marriage. A ‘yes’ pronounced within the present moment and for the present moment, but spoken as an eternal word, for it is consent to the union of Christ with the eternal part of our soul. Norris goes on to say, “In seeking any covenantal relationship we must be willing to say ‘yes’ long before we have a clear idea of what such intimacy will cost us.” I had some idea of the cost of regaining an intimacy with Christianity, with the God of Christianity. At the very least it would cause me the grave discomfort of doubt, for I knew that once I entered the territory of even the most fragile faith, doubt would be my constant running buddy. I had my fears of what the other costs would be—that I would lose my credibility with friends and colleagues, that I might lose friends altogether, that I might even lose my self as I had defined or imagined it. I knew that letting myself be called back into the fold wouldn’t be a matter of saying yes once and for all; it would have to be a daily assenting. In my vocation as a poet, I was familiar with the practice of daily faith-building. Each day my writing called me, its voice trumpeting clear and insistent through the cacophony of competing responsibilities. Too many days I turned away, convincing myself that my paid work as a teacher, my duties as a mother, friend, and wife, were all I could handle in that 24-hour span. But in reality, while these demands all required my time and attention, what kept me from writing was a failure of faith. The crippling fear that, if I climbed the stairs to my study, sat in my flowered writing chair, lit a candle and took up my notebook, nothing might come. It was a real enough fear. Sometimes the angel didn’t show. But if I kept the faith, kept saying yes by showing up on the mornings I had set aside for writing, she usually kept our rendezvous. If there is one thing Feminism has taught me, it is to be active rather than passive. Mary has been reviled by some feminists because she is perceived as passive, as being chosen rather than choosing. But that moment between her and Gabriel is charged with choice. It is the moment suspended between yes and no, and that is what makes it so compelling to me. If the angel doesn’t come to me, I must go to the angel, which I guess is what I did when I went looking for Mary and Gabriel in Florence. And it is what the monks were doing as they paused coming up the stairs, inserting themselves for Mary. Perhaps, unwittingly, despite fear and doubt, I too had been looking for a way of saying yes. Judith Sornberger "Waiting for Gabriel" is an excerpt from Judith Sornberger's book, The Accidental Pilgrim: Finding God and His Mother in Tuscany (Shanti Arts, 2015). Judith Sornberger’s most recent poetry collection Practicing the World was published by CavanKerry Press in 2018. Her full-length collectionOpen Heart is from Calyx Books. She is the author of five chapbooks, most recently the prize-winning Wal-Mart Orchid (Evening Street Press). Her memoir The Accidental Pilgrim: Finding God and His Mother in Tuscany was published by Shanti Arts in 2015. Sornberger has taught creative writing in many venues, including prisons, colleges, and universities. As Professor of English at Mansfield University, she taught poetry and creative nonfiction writing, as well as creating and teaching in the Women’s Studies Program for 25 years. As Professor Emerita, she enjoys a life of writing, reading, and teaching Tai Chi. Damned Vile Race The silver-maned baritone can never sing this air since he has never understood why what we love dies, why his constant headache won’t subside like a wave of strings as he finds his daggered daughter cast to the muck so he cries out so he cries out not for mercy but a tone he’s chased through this cosmos of auroral curtains, through these blinding hemispheres whose thunder falls on his ears like a sentence’s song the Virtues composed in a key they’ve long forsaken. If woman be fickle it is the curse of being human, being subject to a duke’s dominion over all a baleful gaze surveys from a barouche and if this squire be cruel it is the curse of knowledge he can’t escape he can’t escape his vanity and urges, his tenor’s privilege to duel with gods who have no need of courage to face a sudden end, to accept the shockwaves of applause for man’s capacity to tolerate awareness of cadenza of cadenza the baritone alone can deliver from off stage as he removes his costume to burn it in the wings where he flies to the bosom of today, a country free of tyranny, of timpani, of composer’s time out of time so he cries out so he cries out George Guida This poem was written in response to a painting by Andrey Shishkin (Russia, 2013). We regret we were unable to contact the painter for permission, and so have included a scene from the opera on which the painting was based. You can view the artwork here. George Guida is the author of seven books, including four collections of poems, most recently Pugilistic (WordTech Editions) and The Sleeping Gulf (Bordighera Press). The Third of May 1808 What does he see inside the lantern’s light-- before the rifles and about to die? The sun of yellow and the clouds of white. His hands upheld, he does not try to fight. His wide eyes sorrowful, imploring why. What does he see inside the lantern’s light? A friar by his side prays for his plight. A supplication rises to the sky. The sun of yellow and the clouds of white. Beyond the cowering mass, the town in sight. Around him, on the ground, the bodies lie. What does he see inside the lantern’s light? The lantern, too, would see him if it might-- a frightened child, a captured butterfly. The sun of yellow and the clouds of white. The month of May brings rose buds small and bright. Though briars sting, he’d hold them tight and cry. What does he see inside the lantern’s light? The sun of yellow and the clouds of white. Alan Sugar Alan Sugar shares his poetry and performance art in Decatur, Georgia where he currently resides. He is also a puppeteer, and he has worked as a special education teacher in the public schools of Atlanta. Currently, Alan works as a writing tutor at Georgia State University, Perimeter College, Clarkston Campus. His work has appeared in Atlanta Review, The Lyric, The Jewish Literary Journal,The Society of Classical Poets, and RFD. Mona Lisa (c.1503-1507) Leonardo da Vinci Sitter: My maiden name was Gherardini. Had I still retained that claim, eternal fame might not have been my lot. My husband’s name means jocund, happy, never ever sad. "La Giaconda"; double meaning, glad by name, so must be glad by nature. Same in French, "joconde," whichever way you frame it: "jollity," whichever way you add. So come on Leonardo, make me smile. Amuse your muse, do something to beguile and "keep me full of merriment" to chase away my melancholy, also while away the time. So bring me music. I’ll comply and try to keep a smiling face. Artist: An aerial perspective would decrease the space between this muse and background – lake and mountains - merge them into one opaque scene, nature harmonized and of a piece. This natural design would then release her shoulders, place her calmly. I can fake her sweet demeanour, can contrive to take perception to belief. But this caprice for entertainment makes me want to scream in rima alternata. Well, perhaps sfumato might suffice to make her seem, through chiaroscuro, facially to lapse into a sphinx-like smile, appear to dream of secrets older than the rocks, perhaps? Girl with a Fan (1881) Pierre-Auguste Renoir Sitter: Pierre painted a scene from father’s bar, "Le Grenouillere," some time ago, so why return to paint my picture now? I’ll die of boredom. Oh! So hot indoors so far this morning, need to be outside. Mama insists that right away I go and try some dresses on, but father says the high- necked grey, because it suits his little star. I should have worn the blue and white stripe: cool and smooth, like pebbles deep inside a pool and crisp, like beach chairs down at Juan- les- Pins, or table cloths mama puts out for meals in le jardin. But do I need this fan? the blue and white should feel like fresh air feels. Artist: It doesn’t really matter what she wears. It’s Alphonsine Fournaise’s carefree pose, her unaffected youthful charm – just those few fleeting moments frozen - that one cares to capture, innocent, naive. One dares to use an ordinary muse, and chose this girl’s un-classic features, I suppose because I sense some fresh awareness there. But on reflection? No. The greenish-grey the child’s complied by wearing, doesn’t say those things about her. Maybe lapis blue would hint at something wistful in her eyes? A Venus, hearing soft seductive sighs of wavelets curling round her feet anew? Woman with a Fan (1908) Pablo Picasso Sitter addressing Alphonsine Fournaise: And now you see me, Alphonsine. The age- old woman whom you’ve just been listening to. Perhaps you think my head distorted, caged inside a visor’s nasal. Heavy too: its oval forehead, bulbous, over-sized, is pushing outwards, downwards. Thus, I rest my face in Faiyum shadow, leaden-eyed. No youthful bloom. No wistful look. Oppressed. Listen now, and hear my self-composure. I am all the "Labyrinths and Paths with Thunder": earth and fire and air’s exposure. Now Idoto, water goddess; herewith sanctified by oilbean, python, turtle, tortoise. Deified by great Okigbo, soldier-poet, priest incarnate. Tribal mask of Mother Nature known to Igbo. Artist: Her muted palette makes you feed on form. In refutation of mimetic art, this Amazon’s constructions are the norm of basic laws of geometrics; squares and circles, cylinders and cones, not fixed, but shifting images fragmented. There’s acknowledgement to Fetish, but remixed. Perceived as "primitive," the ancient mask has much to teach the Western "civilized." Authentic, Fundamental Life. The casque I gave her for her headwear symbolized her earthy power – terracotta – then the shape inverted for her eyebrows, and her wide closed eyes, allows her to ascend the plane, recede the fan in her right hand. The Uncertainty of the Poet (1913) Giorgio de Chirico Artist: Sometimes, when wandering alone, a "strange sensation" overtakes me. Then I see the world in shades of Nietzsche grey. Do we believe without a reason in a range of value systems? Do I rearrange for Art’s sake laws of credibility? A barren square, a fractured statue – she is headless – meaning empty page? Arrange an Epiphanic Moment! Then, my train of thought, (seen steaming in the background), bound for Arte Metafisica, wonders how these twenty-three bananas should remain so controversial. Hasn’t it been found the metaphysics’ art is molto NOW? Sitter: I’m Aphrodite’s headless torso. That implies I write of love in Grecian tropes. No brainer. That takes care of why and what, but what about to whom and where? One hopes it covers when. And what about the shape of poems? Possibly a sort-of square could quite well mean a Sonnet. Could I scrape a Villanelle or Terza Rima? Bare- ly though, Sestina. What of colour, then? Does virgin white mean writer’s block? I ought to add a dash of blackish. How and when? This writing business needs a bit of thought. Suppose his train of thought went off the rails, and chimed un-rhyming? What would that entail? Stella Pye: Self-Portrait in Green Sitter: My husband’s daughters scan me through his eyes, appraising gazes from their mother’s face. I wonder what they see, and in this case, I’d understand the reasons for their "Whys?" and shouldn’t be surprised, should they despise a woman writing sestets interlaced, a nutcase, sometimes gazing into space, a distant person. Something else besides: Perhaps they see an arid landscape, quite denuded of "do you remember whens?," insider jokes and silly songs. To show my "other" self in halfway-decent light, I might need someone like Rossetti, then again, perhaps someone I know. I know, Artist: I’ll paint my picture through my father’s eye, (he won’t disdain my asymmetric face) and dress myself in green, to signify my gaucheness, "green as grass," and then I’ll place myself before my garden background, green on green. Some better metaphors are new- ness, freshness, germinesse. I may be seen in any sense of greening; someone who is pensive, concentrating on a sound beyond immediacy of singing birds, to disremembered cadence newly found, the fertilizer for unwritten words. An unknown poet wearing unripe dress, still incomplete in incompletedness. Stella Pye The self-portrait that inspired Stella Pye's final poem is imaginary, and the image shown is a placeholder for illustrative purposes. These works are from Stella Pye's upcoming manuscript, Talking Pictures. After retiring, Stella Pye earned her Creative Writing M.A. and PhD at home in the U.K. at the University of Bolton, where she is a visiting lecturer. Her poems have been published in Stand, P&A, The Spectator, Able Muse and Poet and Geek. She is a reviewer for Stand. The House As a paranormal investigator, Jacob’s job is to dig up all the secrets in the world that science cannot explain. Today, he is investigating the dark, looming house on 6th avenue in Marksonville. The owner of the house is said to be a strange, whiskered circus performer. Legend has that she is a possessed woman who kills whoever dares to enter the house. She creeps up behind them with quiet footsteps and slaughters them mercilessly. Jacob enters the mahogany double doors and wanders around the house, which had become shed-like with jagged wood edges. Then, he hears it: thunk, the sound of the woman’s footsteps approaching. Jacob pulls out every trick he knows to scare off evil, possessed souls: shining a flashlight, chanting spells while holding crosses and throwing tiny little metal hearts in the air. Nothing works; the footsteps continue to approach him from behind his back. Jacob is left with no choice but to turn around to face it. He grits his teeth as he turns, preparing to die. He does not see a possessed circus performer; instead, a long-whiskered cat sits in in front of him, striped in orange and white. It opens its mouth; it’s asking Jacob for food. Jieyan Wang Jieyan Wang is a short fiction writer from northern Idaho. Her work has appeared in or is forthcoming in Canvas Literary Journal, Parallax Literary Journal, and Lilun Magazine. She is also a First Reader for Polyphony Literature. Astronomy in the Seventeenth Century You sit in a kimono-like silk robe, observe the Dragon, Hercules, the Bear and Lyra on your multicolored globe, and eavesdrop as they speak of an elsewhere beyond your ken. A manual on the table is open to the saying, "inspiration from God," a practicable guide to enable a man to learn the stars and navigation. How dare you go against the sacred scheme, commit attempts to learn about the earth, the nature of the suns and worlds that beam their facts to prying scientists? A dearth of hands-on research is what they expect. Is that the reason you've no telescope? God's frightened His whole system could be wrecked if you don't wash your notions out with soap. The globe now, in slow motion, detonates, the constellations flung every which way. You fall as your gray matter vacillates between the urge to blaspheme or to pray. Martin Elster This poem won second place in the 2010 Science Fiction Poetry Association contest. Martin Elster is a percussionist with the Hartford Symphony Orchestra. His poems have appeared in numerous journals, including Autumn Sky, Better Than Starbucks, Cahoodaloodaling, Poetry Quaterly, The Flea, The Road Not Taken, and in various anthologies, including Taking Turns: Sonnets from Eratosphere, The 2012 and 2015 Rhysling Anthologies, New Sun Rising: Stories for Japan, Poems for a Liminal Age, and the Potcake Chapbooks. Honors include co-winner of Rhymezone’s 2016 poetry contest, winner of the Thomas Gray Anniversary Poetry Competition 2014, third place in the SFPA’s 2015 poetry contest, and three Pushcart nominations. On Flegel’s Dessert Still Life 1. In a still life with grapes and other points of interest, the eye goes to a glass chalice on a tabletop, notices how those grapes glisten, though not more so than the chalice, sparked by ceremonies of light; how just a few arcs of white, scrapings really, stoke our curiosity. You almost have to dip a finger in to find out if it’s empty or not, so fragile is the distinction between glass and wine. Ask yourself if we aren’t like that, holding emptiness in an invisible embrace, downing it in a thirst for light. 2. But this is only part of the picture. That stilted parrot, for instance, why is it robed in the varnished dark? The white dot on the eye of the mouse offers a glimmer of an answer. 3. Is it greed that gives the gray mouse its appetite for sticky fruits and nutmeats? Or is it desire, the dark in the light that enthralls us and gives us weight? Jerome Gagnon This poem previously appeared in Jerome Gagnon's collection, Rumors of Wisdom (Concrete Wolf Press.) Jerome Gagnon has worked as a teacher, tutor, and freelance journalist. A graduate of San Francisco State University’s Creative Writing Program, his poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Poet Lore, Spiritus, Modern Haiku, Crab Creek Review, and elsewhere. The author of Rumors of Wisdom from Concrete Wolf Press, and Spell of the Ordinary from Finishing Line Press, he lives in Northern California. www.jeromegagnonblog.wordpress.com The Bride Frightened at Seeing Life Opened Her whole life she’d called for the great cracking, imagined it as the laser tap of a Philips head on the hairy chest of a coconut, the sort of drilling that starts slow but winds up sloppy, barely accounting for its mistaps until a divet becomes an invitation, barely containing the spill of its off-white near-sweet lava. Instead, it seemed a tremendous failure in design, so much fruit in reluctant dialogue like the market bounty she’d pour across the kitchen table each morning. It was exhausting, the fruit, with its relentless soft walls, seeds whining to be plucked, sticky faces of plantains glaring petulantly at the coy perfection of kiwi fuzz. Perhaps she’d misunderstood all along, imagining her life a slow dramatic reveal, a careful carving out of her savory youth. Surely she was not meant for blind consumption, her joy raised to a tongue merely wanting breakfast. Juliet Latham Juliet Latham lives in West Chester, PA, where she is a full-time corporate trainer. She holds a masters degree in creative writing and taught writing for 10 years at Temple University in Philadelphia. Her work has been published in a variety of places, including The Journal, Eleven Eleven, Boxcar Poetry Review, Pindeldyboz, The Edward Society, BLOOM, and Monkeybicycle.

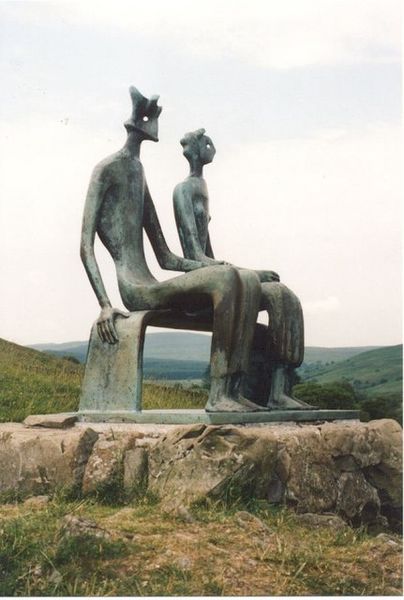

Glenkiln They took them away but the sculptures still stand or recline in a stark landscape of memory like real people lost I am close to the earth: beneath the sky there are swells and surges vales and hollows I remember driving there after an argument, walking the Covenanters' Road as light snow fell, opening up to the land –– a high rugged horizon and the fir plantations beyond The Standing Figure I am lost in the interplay between solid and void there is the closeness of soil and rock the erosion of upheaval I remember especially that day the cold blade of the hills like betrayal I can no longer recline or find my rhythm have lost the freer rounder form of contentment As I clambered up the hill in first light, wet and knees shaking not caring that I kept slipping I found a walled sanctuary of trees where sheep were sheltering and I stopped the sun full on my face Holes through what’s solid some of them accidental a driftwood of organic patterns his wombs wearing helmets I looked down on the King and Queen –- white outlined black –- the cross stark against a pale sky light pulsing on the dark vein of water I returned to them later teetering diagonally down the steep slope held their icy hands in a last farewell, relied on the feel of stone to find direction Jane Frank Jane Frank teaches creative writing and literary studies at Griffith University in south east Queensland, and has qualifications in art history. Her poetry has appeared most recently inNot Very Quiet, Stilts Journal and The Poets’ Republic. It is also forthcoming in Antipodes, Meniscus and anthologies titled Pale Fire: New Writing on the Moon (The Frogmore Press 2019) in celebration of fifty years since the moon landing, and Forty Voices Strong: An Anthology of Contemporary Scottish Poetry (University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, 2019). Find more of her work at https://janefrankpoetry.wordpress.com/ and https://www.facebook.com/JaneFrankPoet/ Editor's Note: The Glenkiln sculpture park was a collection of sculptures bought and displayed by Sir William Keswick between 1951 and 1976, thus realizing his lifelong vision of making the world's first collection of sculpture in a natural setting, the Scottish moorlands. The sculptures included works by Henry Moore, Jacob Epstein and Auguste Rodin. After one of the sculptures was stolen, they were removed from the moors. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|