|

Carol Scheina sat down to talk with children’s author Ted Macaluso, on behalf of The Ekphrastic Review. Ted is the author of Vincent, Theo, and the Fox, which weaves a fantastical story of Vincent Van Gogh through the artist’s works. Ted talked about his experiences in writing the book, and how he used ekphrastic writing to capture the magic he finds in Van Gogh’s paintings as well as to capture the imagination of children. Carol: Can you give a little bit about your background? Ted: I grew up 20 miles north of New York City, and my mother was very artistic. In fact, she became a sculptress later in her life. As a result, I think I visited every museum in New York City at least 20 times before I had gotten to high school. I’ve never had formal art training or taken art history classes, but I’ve had this love of art my whole life thanks to my mother. Where I grew up, we lived on a hill, and there was a place I could walk to where I could look into a valley, much like Harvest at La Crau, which I used with the opening of my book, Vincent, Theo, and the Fox. I would go there a lot just to get away to think. And that may be why I resonated with Harvest, because I had the idea of a boy stopping at a lookout point to think and observe. In terms of writing, I had lots of experience writing nonfiction. I taught political science at the University of Kentucky, and later did research and evaluation studies for the Food and Nutrition service in the government. Writing fiction is a second career. I started taking courses at the Writer’s Center in Bethesda, Maryland, and I’ve been working on it ever since. What originally drew you to Van Gogh's paintings? I was drawn to the paintings Van Gogh did after Paris, where he has all of this colour and the expressionism. When I look at his paintings, I feel suspended between reality and something else, something more. That feeling comes from things like angles being not quite right. For instance, if you look at The Church at Auvers, it looks very close to the real church, but the angles are off and there’s no doorway into it. It’s real but not real. In Starry Night, he uses colours that contrast in a way that makes it look like the stars are moving. All of that drew me to his art; I just loved it. What inspired you to write a children’s book about the paintings? The story began about two decades ago with my son, Mark, who at age five had asthma and had to use a nebulizer machine. Mark had to sit still at the dining room table during his treatment, and one afternoon when he was receiving treatment, he wanted me to read him a children’s story. All the children’s books were elsewhere, and the only book nearby was a catalog from the National Gallery of Art about a Van Gogh exhibit they had recently had. Mark insisted that I read the catalog to him. I found the painting, Harvest at La Crau, it just seemed to me that a young boy, such as Vincent, and his brother could sit there above the fields and talk. That became the start of the story. The cart in the middle of the picture, which is the focal point of the image, is fascinating. I wondered if farmers could store their lunch there, and if you have lunch, an animal like a fox could go after it, and if he did, he’d get into trouble. Thus, I had three characters: the fox and two boys, the beginning of a plot, and a reason to move on to another picture. That day, I made up a really disjointed story, but Mark loved it. He wanted me to write it down, and then, I wanted to do it really right. That grew into a process of thinking about what makes for a good story and looking at lots of Van Gogh paintings. I would flip back and forth through paintings, thinking about them from a story perspective. Who is this fox? I thought, well, he’s young like Vincent and Theo. He is new in the world and wants to find things out. He’s curious, and he therefore is going to try things like Vincent did. And also, he’s hungry. And so, I thought that sounded like the start of a story. Often, something in a painting would send the story in a new direction. Then I realized the fox was young and didn’t know what he was going to do, so new story directions were fine. Just like any kid, he would have to figure out life. I think a lot of kids can relate to that theme, and that question of what am I going to be when I grow up. Why did you feel inspired to use a fox in your story? The fox just came to me; I didn’t analyze it much at the time. I wanted to use an animal rather than a person because it was for kids, and it would be interesting. My subconscious knew I needed an animal that would be plausible in the French countryside, so I couldn’t have a cute cuddly panda bear. It also had to be a wild animal, therefore dogs and cats were out, and so I picked the fox. Also, there is no fox in any of Van Gogh’s paintings. You cannot find one, so the readers need to use their imagination to put the fox in those scenes. As soon as you look at the paintings, they all open up different things. For example, when they were going through the woods, you can wonder, is the fox behind a tree in the painting? How did the fox get through? I like the way that you can look at one of the paintings and imagine a fox walking up the street. It was a very interesting journey writing this. You blended a bit of Van Gogh's real-life history, his paintings, and an imagined storyline. How familiar were you with Van Gogh's life beforehand, and did that help inspire your story? I was broadly familiar with Van Gogh, but not an expert. I realized that I was writing about a real person, so it had to be realistic. I couldn’t contradict his real life, so I did a lot of reading and research. I think that’s important, because if you’re drawing inspiration from artwork, your imagination can run to many places. Since this was a real person, I couldn’t have the story contradict the events in his life. Van Gogh tried a lot of different careers. He didn’t settle on painting until he was in his late 20s. He tried all these different careers. I had the fox in my story do the same thing, try lots of different experiences. Van Gogh was always searching for something in life, so my story parallels that in that the children reading it can also have a quest through his pictures. Do you feel this story will help Van Gogh resonate with children? How do you feel ekphrastic writing resonates with children? I hope so. Some of the reviews I’ve had say that their child loved the story, and guessed where the fox might be on every page. I do think ekphrastic writing is right for kids because that’s how so many of them look at the world. They look at what’s around them, and especially at artwork, and make up stories to explain it or interpret it. They’re not confined by the barriers we create as adults, or that are forced on us as adults. I think ekphrastic writing is one way for adults to become childlike again, to free their imagination. Do you have plans for future ekphrastic books for children? I’m working on a young adult novel right now inspired by a Russian painter, Ivan Aivazovsky. He isn’t well known in the United States, but he was very famous in Europe, and he made hundreds of paintings. He was the official painter for the Russian navy. His paintings just grabbed me when I saw them. It’s just this romantic adventure world, sort of like Treasure Island. I’ve also been working on a children’s book, Seeking Cezanne, which is similar to my Vincent book. It’s aimed at kids, and it involves the art of Cezanne and some other artists as well. Was there one painting that resonated with you the most while writing this story, and why? There are three, actually. Harvest at La Crau is the very first one. It started the story, Vincent, Theo, and the Fox, and as I said, maybe because I grew up on a hill, I could just picture Vincent and Theo being there. Looking at that field and at the blue cart that’s the focal point. It’s oversized, it’s so big, it doesn’t look real. And doesn’t it make you want to explore it, the way it draws you into it? It’s just mysterious because you have an oversized cart, you have something that looks like a very beautiful pastoral scene but next to the cart, there are wheels for a different cart that are almost like day-glow orange. They look like they’re just burning with some otherworldly light. You’re also looking at the fields, and they’re all geometric and regular. That image always stuck with me. I resonated with Wheat Field with Crows, which is one of his most famous paintings and is featured as a two-page spread in my book. I love how expansive it is, and it’s just a beautiful portrayal of darkness and light. It has a trail on the left approaching the viewer, then curving away, symbolizing life and death and the human journey, or the joy of being outdoors in the field. The third painting is Starry Night. I’m not the only one who thinks it’s genius, but it really is genius. In person, it’s so small you don’t believe it, for it looms so large in the public’s consciousnesses. I didn’t know this when I chose it, but the stars emulate fluid dynamics. He used colours that complement each other in such a way that your eye thinks they’re moving. They’re just mystical and living. You have the comfort of that sleepy little village, which contrasts with the church that’s completely dark. Its spire ends in one of the few black points in the sky. But you still have the stars to tell you that there is a God. What’s more, it has flowing hills, and the hills were very important when crafting my book because I figured that’s where a fox could be. I had to end the story with that painting because the fox is free and Vincent is happily dreaming that the fox is running wild and free under a starry sky. That aspect of both wild and free, I think, was perfect because that’s the perfect end for the fox, and it also sort of describes Vincent’s artwork. His work was really wild for his time, and he broke conventions. I view many of Van Gogh’s paintings as seeing the magic just beyond what you’re looking at. Vincent: Theo and the Fox by Ted Macaluso Owls Cove Press, 2019 Click here to view or purchase. ** Carol Scheina is a speculative fiction author who also works as a technical editor in the Washington, D.C. suburbs. Her short stories have appeared in Escape Pod, Daily Science Fiction, The Arcanist, and other publications. You can find more of her work at carolscheina.wordpress.com.

1 Comment

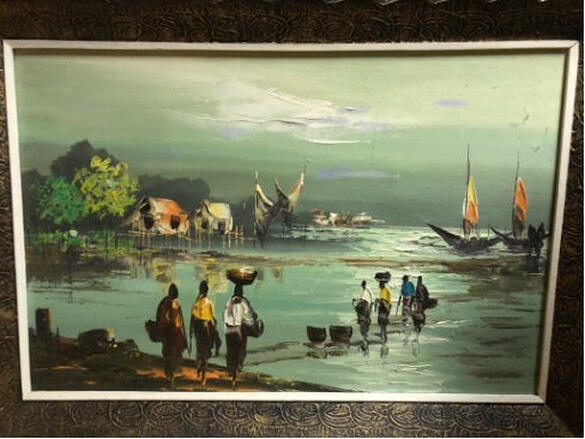

The Catch Low tide. Four dark fishermen wade in from off shore. Three stand at the green water edge. Cloth pants heavy with the sea and black sand surges at ankles. Fish flash silver in grass baskets. Boats, slack and splintered, anchor into silt. Two shacks on stilts, standing high over water like egrets poised for flight. An ivory reflection of twilight clouds. Long shadows. Somewhere on this canvas of brooding green, coral, and black hide my sister’s small fingerprints. Her imprints recollect the viscosity of the oil paint, how it beckoned. How it hardened into the topography of dreams. From the wall in a wintry place halfway around the world from its birthplace, it whispers of soft nights and sweet fat sausage over white rice, of salt cracking on our skin and sand crunching between our molars, of the thrumming, enveloping glow of those carrying our murmuring blood. Trace the strokes, and know that we are suspended between day and night, water and shore, leaving and coming, thirsty and slaked. Cast the net and pull in an absence. An ache. A touchstone. A heartbeat. Ann Guy Ann Guy: "This is a poem inspired by an oil painting that my father bought in 1971 from an unknown street artist in Cebu City, Philippines. The paint was still wet when he brought it home, and it traveled with us to the midwestern United States when we immigrated in 1975." Ann Guy is a writer and recovering engineer in lockdown with her husband and two young children in Oakland, CA. She received her MFA in Creative Nonfiction in 2020 and her MA in English with Creative Writing in Fiction in 2018 from San Francisco State University, where she received a Distinguished Graduate Award from both programs. Her writing has appeared in Entropy, Motherwell, and elsewhere. She is currently at work on a memoir about identity, loss, and resilience. The big news of the year is the new Ekphrastic podcast with Brian A. Salmons. There are six episodes so far.

Listen to all of them here. Episode 6 features Brian reading works by Saad Ali, Alarie Tennille, and Anita Nahal. Click on image above and treat yourself to an amazing poetry reading. The new challenge is up! You have two weeks to write and submit a story or poem inspired by this painting. Click here or on image above for instructions and details.

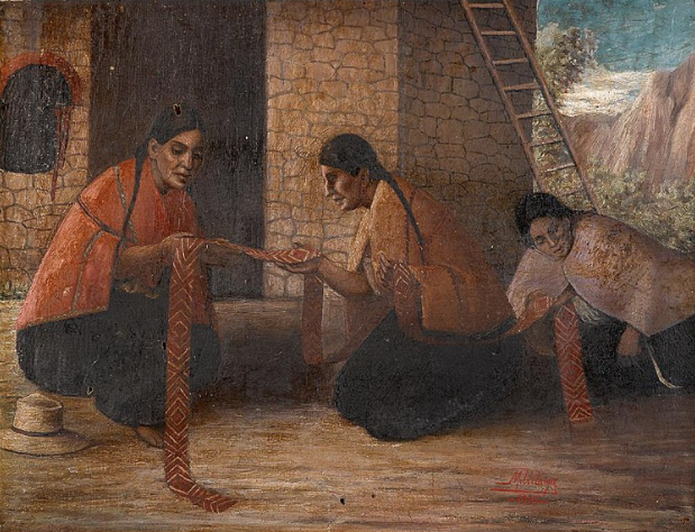

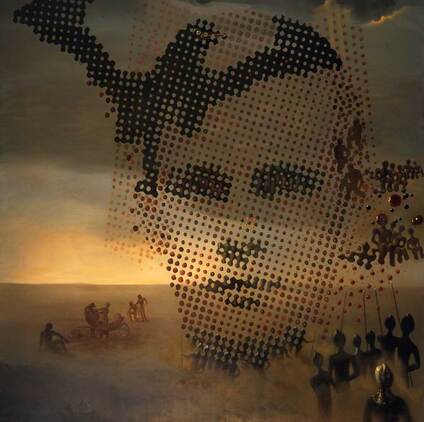

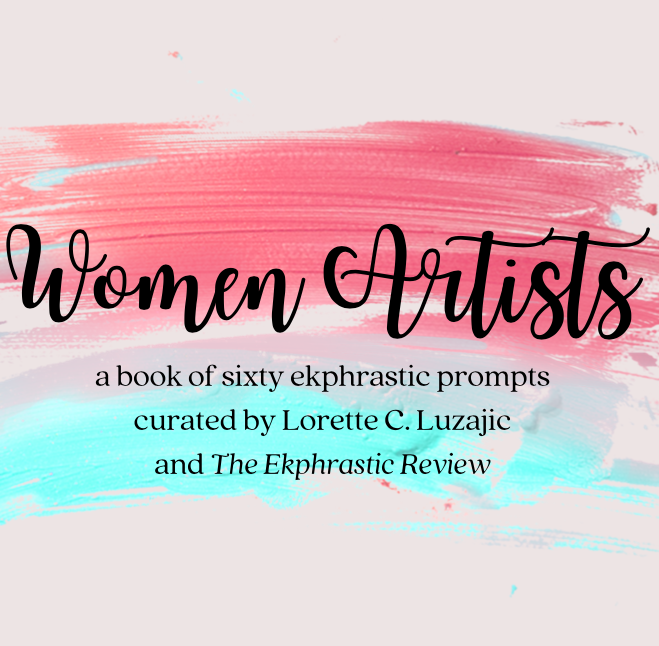

You Cannot See, by Mary Stebbins Taitt The disassembling of the cowboy painting by Edward Marsh was successful. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/you-cannot-see-by-mary-stebbins-taitt ** John Roddam Spencer Stanhope's Eve Tempted by the Serpent, by Stephen Gibson A poem of a hooded temptation. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/john-roddam-spencer-stanhopes-eve-tempted-by-the-serpent-by-stephen-gibson ** The poems of the Viktor Gontarov challenge. The Matskiv Family Collection also featured the poems on their website! https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/ekphrastic-challenge-responses-viktor-gontarov http://matskivcollection.com/2019/12/ekphrastic-challenge/ ** tea in the bedside by Annest Gwilym A poem inspired by Harold Gilman's painting. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/tea-in-the-bedsitter-by-annest-gwilym ** The poems of the Henri Regnault challenge. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/ekphrastic-challenge-responses-henri-regnault ** The poems of the Matthew Rackham Barnes challenge. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/ekphrastic-challenge-responses-matthew-rackham-barnes ** Winslow Homer's Sharpshooter, by Joseph Stanton The first poem in the set of five. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/five-poems-on-winslow-homer-by-joseph-stanton ** The Pen of Plenty (or A Portrait of an Artist as the Entire Universe), by Boris Glikman A story about The Writer inspired by M.C. Escher's Drawing Hands. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/the-pen-of-plenty-or-a-portrait-of-an-artist-as-the-entire-universe-by-boris-glikman ** Icarus, Revisited, by Lorette C. Luzajic A poem inspired by Herbert Draper's Lament for Icarus. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/icarus-revisited-by-lorette-c-luzajic ** The Giant Egg, by Boris Glikman A story inspired by Vladimir Kush's Sunrise by the Ocean. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/the-giant-egg-by-boris-glikman ** Paula Puolakka (born August 18, 1982) is a Beat poet, writer, and MA (History of Science and Ideas.) In 2017, her first book of poems, Näkymättömän naisen isku (Mediapinta: Tampere) was published to celebrate Finland's 100 years of independence. In 2018, her second book of poems, TESTAMENTTI: joutsenlaulu turhuuden turuilta was published. Also, in 2017, her three short novels CAIN, The Garden of Eden, and ADAM were published by the UK-based Michael Terence Publishing: she was using the pseudonym Paula St. Paul. Puolakka has landed first and second in various writing competitions and challenges. She has, also, been given honourable mentions and honourable anthology slots, for example, by The Finnish Reserve Officers' Federation, Tiny Spoon Lit Mag, Woody Guthrie Poets (USA,) and AQB (UK.) In December 2020, her academic article was published by the university and science magazine Hybris (Tampere University) to celebrate her Master's thesis of 2012 and the academic legacy of Mr. Kaczynski and Mr. Wittgenstein. Be a guest editor for a Throwback Thursday! Pick up to 10 favourite or random posts from the archives of The Ekphrastic Review. Use the format you see above: title, name of author, a sentence or two about your choice, and the link. Include a bio and if you wish, a note to readers about the Review, your relationship to the journal, ekphrastic writing in general, or any other relevant subject. Put THROWBACK THURSDAYS in the subject line and send to theekphrasticreview@gmail.com. (Send anytime- no need to wait for a particular submission period.) Along with your picks, send a vintage photo of yourself! Vertigo Spoiled Our Last Meal His whisper – the unexpected unfurling of his sin, soured and hot – spilled from my ear, trickled dripped then mixed into the tomato bisque I’d whipped up for dinner – leaving it unfit, even for the half-starved dogs who prowled our woods. Kari Ann Ebert Kari Ann Ebert is the Poetry & Interview editor for The Broadkill Review and the Project Director of Downtown Dover Poetry Weekend. Winner of the 2020 Sandy Crimmins National Prize in Poetry, the 2019 Crossroads Ekphrastic Writing Contest, and 2018 Gigantic Sequins Poetry Contest, Kari’s work has appeared or is forthcoming in journals such as Mojave River Review, Philadelphia Stories, Main Street Rag, The Ekphrastic Review, and Gargoyle as well as several anthologies. She has been awarded fellowships from Delaware Division of the Arts (2020), The Shipman Agency (2020), BOAAT Press (2020), and Brooklyn Poets (2019). Portrait of My Dead Brother, 1963 Surrealist artist Salvador Dali had a brother who died in infancy nine months before Dali's birth. Dali's parents took their five-year-old son to his brother’s grave and told him he was the reincarnation of his brother. You were first. I followed. I was born from your death, a Phoenix rising from your grave. I picked up where you left off. I am the two of us. I am a broken twin. This canvas is a mirror. It is slowly gathering your forgotten face, the lost parts coming together like a flock of dark seagulls moving into formation. It is my face but strangely different. It is a soft clock with no hands. You are a shattered constellation collecting your own wandering stars. After sixty years I can finally see you. When I die, you shall see me. Then, we will share your constellation. You and I, Gemini, unbroken, healed. Kathryn de Leon Kathryn de Leon is from Los Angeles, California but has been living in England for eleven years. Her poems have appeared in several publications in the US including Aaduna, Calliope and Black Fox, and in several in the UK,including London Grip, The Blue Nib, and The High Window where she was the Featured American Poet. Death and the Miser Consider the banality of choice: the crucifix’s slivered light against a bag of gold Death’s arrow nears to pierce the heart yet even as a demon leers and holds the promise of a cinder’s heat the miser’s hand moves of its own accord to that which cannot follow him And as if memory the miser’s younger self appears to stash another coin inside a bulging sack he locks away and does not see the rat-faced beast that grips the sack in appetite that turns its head against the miser’s fumbled rosary One can not help but wonder at the artist’s mind: the fevered brain that drives a man to see the world as such a dream the hours spent entranced before a sheet of stainless white the images that flittered in the eye but died before they reached the page And more consider all the children screaming at the artist’s feet the open mouths that cried for milk or bread while father bled his mind to find the perfect line to smear So much depends upon so small a cost And yet the man who meets his leaving doesn’t see the beasts that slither on the floor nor does he note the seraphim that spreads its hand toward the lighted crucifix Instead he stares at Death itself as if he’d wished to somehow ward it off as if its flesh- less face was not expected stares in fact as if he hadn’t seen that everything including Death is somehow owed a wage Jon D. Lee Jon D. Lee is the author of three books, including An Epidemic of Rumors: How Stories Shape Our Perceptions of Disease and These Around Us. His poems and essays have appeared or are forthcoming in The Atlantic, Sugar House Review, Sierra Nevada Review, The Writer's Chronicle, One, The Laurel Review, and The Inflectionist Review. He has an MFA in Poetry from Lesley University, and a PhD in Folklore. Lee teaches at Suffolk University. With just a couple of weeks left for our Bird Watching contest many of you have already sent your entries and are ready for another major ekphrastic writing challenge. We have gathered another intriguing collection of artworks, and the theme this time is Women Artists. Artists throughout history in many different cultures faced immense obstacles, and women even more so. Few female painters or sculptors have been acknowledged by history or books, and yet we have a rich legacy of creativity if we dig between the lines to find gold. The subject was so exciting that I got carried away. It was my intention to select 30 to 40 prompts to inspire your ekphrastic writing practice, but ended up with 60. Many more were left on the cutting room floor. I hope each artwork will lead you to study more works by the featured artists, to learn about their lives and work and the worlds they lived in. Use your ebook of 60 artworks as a reference and a book of writing prompts, now and forever. Purchase before the contest deadline also qualifies you to enter up to ten poems or stories. Selected entries will be published in The Ekphrastic Review, in a series of special showcases. We are absolutely delighted to have Alarie Tennille as our guest judge. Alarie is a long-time contributor to the journal, a consultant for our prize nominations, a winner of our Fantastic Ekphrastic Award for her outstanding contributions to the journal and to ekphrastic literature, and a widely published and loved poet. Alarie will choose a first place winner and two runners up from the published selections. The first place entry will receive $100 and each runner up will receive $50. Winners may be flash fiction, creative nonfiction, or poetry. Your purchase of our ebooks has made it possible for us to offer cash prizes in these new contests at The Ekphrastic Review. Your support also helps with the time, maintenance, web and other expenses, and promotion of this journal. We can't thank you enough. RULES 1. Click on button below to get your ebook of sixty prompts by women artists. 2. Write from any or all of the artwork prompts. You may submit up to ten pieces. 3. Please submit all of your entries in one email. Wait until you have your complete entry to send. 4. You may write poetry, flash fiction, or creative nonfiction, or a combination, up to 1000 words each. 5. Deadline is July 7, 2021. 6. Send your entry to theekphrasticreview@gmail.com. In subject line, put WOMEN ARTISTS CONTEST. 7. We hate to censor your creativity and will try to accommodate experimental formatting, but be aware that flush left formats work best for the web. Complicated formats or spacing is difficult or impossible to reproduce faithfully. 8. Your work must be inspired by the prompts in the book. They can incorporate a description of the art or connect to the artwork's history or subject matter, or to the artist biography, or they can use the art as a point of departure for imagination, memory, correlation, etc. In other words, the writing can be about the art or about anything else the art triggers you to dream up. 9. The Ekphrastic Review will publish selected works in special showcases from the entries. Of these selections, guest judge Alarie Tennille will choose her favourites. The judge's decisions are final. 10. The winners will receive $100 CAD for first place and $50 each of two runners up. Winners will be paid by PayPal. 11. Winners will be chosen and announced by the end of July 2021. 12. Please include a third person biography up to 100 words. 13. Please use copy and paste in body of email, or a word document. You may include a PDF to show formatting and italics, but please include it in addition to your copy and paste or word document. 13. Good luck and have fun! Dear Ekphrasists, Welcome to the forth installment of the Ekphrastic Writer’s column. As the author of the first comprehensive guidebook on multi-genre ekphrasis, The Ekphrastic Writer, I’ll be posting monthly musings, fielding your questions on ekphrasis (and beyond), and fostering a conversation on contemporary practices in visual-art-influenced creative writing. Happy National Poetry Writing Month! Before I respond to a couple of letters, I want to share a tribute. Late last year I had written a letter to the wife-husband editorial team of the first journal dedicated to ekphrasis: Ekphrasis—A Poetry Journal. The year was 1997. The World Wide Web was in its infancy and the term “ekphrasis” was foreign to everyone but a few literary scholars. Carol and Laverne Frith created a small, loose-leaf journal which they secured with staples. If you were writing poems influenced by the visual arts back in the late nineties and early aughts, you dreamed of placing your poems in Ekphrasis. Back then, physical dictionaries did not include “ekphrasis” and the word was not Internet-searchable until around 2004. While I myself knew the types of poems the highly discerning Friths where seeking, I assumed that the journal’s title was just a unique name with no grand meaning. As a young writer, Ekphrasis was the first place that I could actually read poems by poets who engaged with the visual arts, such as Peter Cooley, Grace Bauer, Jeffery Levine, and David Wright. Back to my letter. My guidebook on ekphrasis had been released and I wondered about the Friths’ journal and succession planning. I’d sent several emails that had gone unanswered, so I composed a handwritten letter and sent it to California. “I’m so grateful to you both for the work you’ve done for the world of ekphrasis,” I began. However, months later a terrible thing happened, which I shared in a desperate post on Facebook: “Writer friends, please help. A letter I wrote to Laverne and Carol Frith was returned with the word “deceased” scrawled across the envelope.” Once I received confirmation, I wrote this next post: “My heart is heavy as I announce that Ekphrasis—A Poetry Journal has folded (and the website scrubbed from the Internet) after nearly a quarter century. Founders Carol and Laverne Frith both passed away, in May 2020 and December 2020 respectively. Today I celebrate the Friths having championed ekphrastic poetry at the dawn of the ekphrastic movement. While journals that tout ekphrasis will continue to come and go, theirs was the first. Thank you for paving the way, Ekphrasis editors.” Here are excerpts from some letters that I received in March: Dear E.W., My question is....what ekphrastic poems about music rather than visual art can you recommend? Signed, Seth C. Dear Seth C., The grandfather of ekphrastic scholarship (insofar as “ekphrasis” is a subgenre of creative writing), James A. W. Heffernan, defined the term thusly: “verbal representation of visual representation.” So, the term ekphrasis as set forth by scholars limits “ekphrastic poems” to those that concern only visual representation. Hence, while there are indeed music-influenced poems, it’d be antithetical to the literal definition of “ekphrasis” to label them as ekphrastic. Furthermore, it’s worthwhile to note that when writers call their poems “ekphrastic,” they are choosing to inform their readership of the genesis of their inspiration. In every one of my ekphrastic poems, for example, I both use the artworks’ titles as the poems’ titles and I include citation epigraphs. While it’s possible that we’ve all read music-influenced poems, if the writer chose not to indicate to the readers that specific fact, then the poems cannot be categorized. The readers’ curiosity about the poems’ origin, as it were, remains a question. It is interesting to note the inherent transparency in “ekphrastic” poems’ influence, as compared with non-ekphrastic poems in which we cannot know, and perhaps are happily ignorant, to their origins. (By the by, it’s not the poets’ responsibility to offer any caveat to their readers. Poems should stand on their own.) Yet, if one simply embraces “ekphrasis” as synonymous with “description” (as in the Greek term, “ekphrasis”) in the spirit of naming music-influenced creative writing, it’d be wise to offer a prefix byway of specifying a musical relationship. In my guidebook on ekphrasis, I coined “phonoekphrasis” to specify verbal representation of sound elements of artwork (which could include other disciplines besides the visual arts, I suppose). So, to answer your question, I recall poems by Langston Hughes which evoke what were then called Negro hymns and spirituals, as well as the prose of Gregory Spatz, who’s also a gifted violinist and thus writes poignantly of playing music. On the Poetry Foundation website, you can search “poems about music” for an exhaustive display of both poems and prose that, in some way, treat music. As an ekphrastic practitioner, what I also find fascinating is the ways in which the visual arts have been informative to composers. For example, a musical composition influenced by artwork, and aptly called, “Pictures at an Exhibition,” is a suite of ten pieces composed for piano in 1874 by Russian composer Modest Mussorgsky. Also, I recommend Siglind Bruhn’s 2000 nonfiction book, Musical Ekphrasis: Composers Responding to Poetry and Painting. Dear E.W., A friend of mine, after reading something I wrote about a historical character, suggested there was too much of myself in the poem. And I thought, isn’t that the point? If there is nothing of us in what we write, then it has no emotional core; it’s flat prose, not poetry. Signed, David B. Dear David B., I can think of very few things more injurious to a writer than an indelicate reader. Readers who know us personally are perhaps the worst providers of feedback, for they lack objectivity and they’re offended by the notion that they’re interlopers to our creative process. I implore everyone: If you chose to share your work with people close to you, ask them to do one of two things: “Please just read this for enjoyment, as I require no feedback.” Or, “please read this and indicate to me the places in which you were confused.” Most people have fine intentions, but it’s your job to direct them to a response that supports your creative process. Instead, allow only your instructors, workshop members, and editors to provide you with critical assessments. Last December I attended a virtual event hosted by Middlebury College which featured Julia Alvarez (poet, novelist, and essayist). During her talk, Alvarez offered this brilliant articulation of the creative writing/creative writer relationship: “Every novel is emotionally autobiographical,” she opined. Remember the adage, “writers don’t write about feelings, they write with feelings”? What we feel is highly specific and autobiographical. If what we’re writing has been enlivened by deep imagery and particularities, we are necessarily writing from the wellspring of truth. Not truth in terms of verifiable facts about our lives, but the emotional and bodily truths. In other words, if you (the writer) believe it (can imagine it), then you can embody it, which can result in a sense of truth-telling for your readers. If you wish to join the conversation, send your letters to E.W. at ekphrasticwriter(at)gmail.com. Ekphrastically Yours, E.W. Post Script—Biographical Note: E.W. (Janée J. Baugher) is the author of The Ekphrastic Writer: Creating Art-Influence Poetry, Fiction and Nonfiction, as well as the ekphrastic poetry collections, The Body’s Physics and Coördinates of Yes. Recent work has appeared in Saturday Evening Post, Tin House, The Southern Review, The American Journal of Poetry, and Nimrod. Her writing has been adapted for the stage and set to music at venues such as University of Cincinnati, Interlochen Center for the Arts, Dance Now! Ensemble in Florida, University of North Carolina-Pembroke, and Otterbein University, and she’s performed at the Library of Congress. Currently, she teaches in Seattle and is an assistant editor at Boulevard magazine. www.JaneeBaugher.com. Follow her on Instagram: @ekphrastic_writer. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|