|

Lady Digby on Her Deathbed "When does grief become wonder?" —Marianne Boruch His dear wife died in the night, so young, so lovely, but the colour gone from her cheeks so they rubbed them to bring it back, and called in his painter friend, who posed her on an angle, one eye slit open, as if still sighted. Her lord never remarried. The painting holds his grief. Van Dyck lives on as well, in shades of cream and white, the soft rose of her lips. Since his object was to console, he stepped back in time to the moment before her death. Being expert with folds and shadow, he opened the purple drapes, the darkness she lies between, and laid gold trim on her blanket, scattered petals on the sheet, the damask blooms she loved, whose sharp cinnamon odor fills the spousal room and pricks our nostrils too, as with barely a hint of a smile she draws her final breath. John Morgan This poem first appeared in Archives of the Air (Salmon Poetry, 2015) John Morgan has published six books of poetry and a collections of essays. His work has appeared in The New Yorker, Poetry, The American Poetry Review, The New Republic, The Paris Review, and many other magazines. He has won the Discovery Award of the New York Poetry Center, and his Collected Poems, 1965-2018 will be coming out next year from Salmon Poetry. Morgan divides his time between Fairbanks, Alaska, and Bellingham, Washington. For more information visit his website: johnmorganpoet.com

0 Comments

Splashed Ink Landscape, by Sesshu (Japan) c. 1495

A quick brush has extracted a foreground tree from a grisaille of mist. Beyond, smooth rocks rise toward Heaven. Rocks of harmony, beauty and repose where a holy hermit like Cold Mountain might live. Many possibilities exist even with grayscale and a playful approach to perspective and proportion. Stop. The painting says none of this. Look, simply look at the picture. Can you? Quick, bolt the door before the mind barges in. Difficult, isn’t it, to simply look, to be right there when brush touches paper? Mike Dillon Mike Dillon lives in Indianola, Washington, a small town on Puget Sound northwest of Seattle. He is the author of four books of poetry and three books of haiku. Several of his haiku were included in Haiku in English: The First Hundred Years, from W.W. Norton (2013). Departures, a book of poetry and prose about the forced removal of Bainbridge Island’s Japanese Americans after Pearl Harbor will be published by Unsolicited Press in April 2019. Sappho

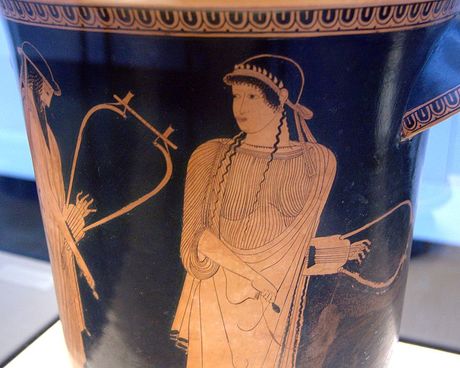

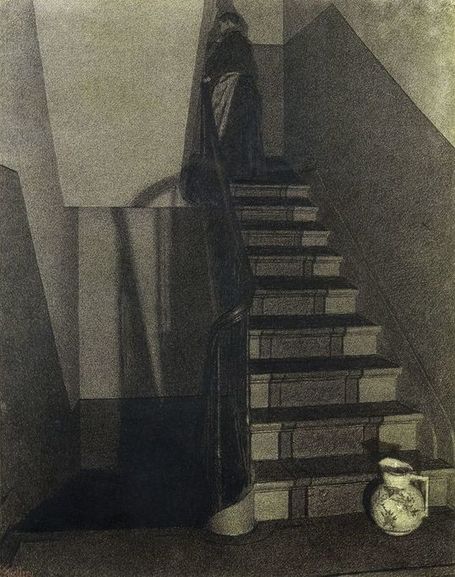

"Someone, I tell you/will remember us./We are oppressed by/fears of oblivion." —a Sappho fragment Two Roman busts have come down to us, both copies of supposed earlier Greek originals, from the 4th. century BC. One has two long stylized hair locks flowing down the bust’s front to where her breasts would be if the modest marble had presented us with such. Her locks flow as multiple stylized curls, crescent-like across her forehead. The second Roman bust, from another lost Hellenistic original, shows Sappho with shorter hair tucked under some kind of band around her forehead—while slipping beneath the band short, slightly curly hair runs along the sides, revealing her ears. Her lips are fuller here and the nose prominently Roman, which has suffered some kind of desecration or damage. Her eyes and slightly tilted head seem pleading, or perhaps only in pondering thought. An early depiction of Sappho also survives on an Attic red-figure kalathos, a kind of ceramic vase in the shape of a household basket.Here she is holding a plectrum and lyre while turning to listen to her contemporary poet-friend Alcaeus, also holding a lyre. Another Greek pottery vessel, used for carrying water, a two-handled kalpis, depicts Sappho on a more common black-figure Greek vase. In both red and the black figure depictions she has long hair either in a bun or cascading double twists of breast-length curls. Little is known about her for certain--although her now mostly lost poetry was well known and much praised through antiquity. Sappho's poet-friend Alcaeus remembers her thus: "Violet-haired, pure, honey-smiling Sappho.” Ed Higgins Ed Higgins' poems and short fiction have appeared in various print and online journals including recently: Sun Journal, CarpeArt Journal, and Tigershark Magazine, among others. He is Professor Emeritus and Writer-in-Residence at George Fox University, south of Portland, OR. He is also Asst. Fiction Editor for Ireland-based Brilliant Flash Fiction. Ed has a small organic farm in Yamhill, OR, raising a menagerie of animals including an alpaca named Machu-Picchu. Melancolie inspired by the statue by Albert György Today, you frame a silver sky, but whatever the weather, as seasons revolve one to the next, beginning, ending only to begin again, what remains, is your embrace of hollowness. Your body, a black outline, emptied, waiting as it holds the light and dark of a day filling you without being part of you-- an outside breathing that cannot touch your inner space. I want to hold your crossed hands-- I want to know their story, how they have become worn. I want to believe in the possibility of their patina polished as if once, touched and loved, touching and loving. I want to believe that in spite of everything, your hands stripped to gloss, are testimony to what makes your head hang so heavy in the emptiness of your wracked arms-- and to that possibility of touch and love. Kitty Jospé Editor's note: The poet was inspired by the sculpture, Melancolie, by Romanian-born sculptor Albert György. The image shown is a placeholder because we were not able to contact the artist. We encourage you to click here to see the image that inspired the poem. Kitty Jospé: "After retiring as French professor, I completed a low-residency MFA at Pacific University in 2009, and teach ekphrastic writing in summer to teens at our local literary centre which is a short walk from the University of Rochester museum, Memorial Art Gallery, where I have been a docent since 1998. I also give lectures on bringing poetry alive by careful study of art."

California Art Collector What I have collected I have collected for you, my love, however, before I die, I wish to bequeath my priceless collection to the poor - whom I love almost as much as I love you. Life happens as a series of epiphanies. For instance, on waking this morning, I knew what I must do. Do something now, I thought, don’t do it for posterity, now is about to happen, now is almost upon us, the immediate future groans imperceptibly, impatiently beckoning us just off the page, live in the moment, your tears belong to the past. I possess treasures that beggar the imagination, stupendous artifacts, all of it quite meaningless until this morning. To spend a lifetime collecting without sharing is nothing less than futile. Come into my house now. Tear down the doors with your bare hands. Take what you will. I am reborn. I feel like Krupskaya feeding the ragged children inside the Winter Palace. I wonder what you will make of my Rothkos and Pollocks, they are yours now, do with them what you will. I always had a sneaking feeling that art belonged to the people. Mark A. Murphy This piece is from the poet's manuscript, Our Little Bit Of Immortality, poems inspired by David Hockney's artwork. Mark A. Murphy was born in West Yorkshire in 1969. He has been published in over 180 journals and ezines. His first collection, Tin Cat Alley was published in 1996. His next collection, Night Wanderer’s Plea is due out this September from Waterloo Press in the UK. Late Turners

Under the weight of a thickly painted moon, keelmen heave their load of coal in the viscous light, bringing it to Newcastle. On the right hand, torches and small fires illuminate their toil, pierce the haze from factories on the shore. The sky’s an argent smear. “Cobalt was good enough for him,” one critic sniffed, not the fancier and more expensive ultramarine. Every age has its critics, n’est-ce pas? They carp and snivel around the edges, fail to see the forest for the brushstrokes, the celestial city in the centrifugal clouds. Later, Turner painted “Peace—Burial at Sea,” which someone snipped could read just as well upside down. He was mourning Scottish painter David Wilkie, and said about the black sails, “I only wish I had any colour to make them blacker.” The dark boat floats on the oily sea, its single sail, a dagger in the chest. He kept on painting, attacking the surface with his palette knife, the swirls getting wilder, the heart’s vortex, dissolving the distinction between water and air, the imprecise measure of fog and smoke and sky. Barbara Crooker This poem was first published in Barbara Crooker's book, More, C&R Press, 2010. Barbara Crooker is the author of eight books of poetry; Les Fauves is the most recent. Her work has appeared in many anthologies, including The Bedford Introduction to Literature, Commonwealth: Contemporary Poets on Pennsylvania, The Poetry of Presence and Nasty Women: An Unapologetic Anthology of Subversive Verse. www.barbaracrooker.com The Angel Gabriel Talks Annunciation to Mary Before he’s said a word, even as he bends the knee and rears his wings in golden branches that wow them every time (the more the little peasant is impressed, the faster this will be) his eye is mournfully absorbed in what he sees. She’s still a child, he can smell honey and dairy on her, and just now she secretly put out a finger in wonder to touch a feather. Gabriel lugs the huge gold nugget words Messiah baby into the conversation early, dazzles those big eyes: but he saves the awkward Crucifixion, with its spiky thorns, for later, or never. Also, wrong time to mention five wounds, or drop those bricks lash, wood, nail, storm, tomb. Leave it to life to tell her. After all, he’s not lying: she will bear the main earthman of all time. She’ll lose him, but time chars all our beloveds. Gabriel sighs just once. Then like the whip-length of snake who first sold Eve the apple he fixes Mary with a gaze bright and old as quartz in granite: Have I got a sweet deal for you. Margaret Benbow Editor's note: This poem was written as a meditation on the painting, Annunciation, by contemporary American artist John Collier. We were unable to contact the artist to show his work here, but encourage you to click this link to see the remarkable art that inspired the poet. Margaret Benbow: "I'm a poet and fiction writer. My first collection of poems, Stalking Joy, won the Walt McDonald First Book Award and was published by TTUP press. A collection of stories, Boy Into Panther, recently won the Many Voices Project Award in Fiction and was published earlier this year by New Rivers Press." Aftermath "belt buckle father coming up the stairs" —Henry Crawford, "Forsaken" Smothered weeping of the beaten child, sound she knows well. Will she be allowed in? Did the child lock the door after the father finished? Will she have to turn, descend the stairs, lift the pitcher, proceed with her task? She's smothered the same sound herself, many a time, and the child has come to her door and found it locked. Shirley Glubka Shirley Glubka is a retired psychotherapist, the author of four poetry collections, a mixed genre collection, and two novels. Her latest (just published!) poetry collection is Through the Fracture in the I: Erasure Poetry; her most recent novel: The Bright Logic of Wilma Schuh. Shirley lives in Prospect, Maine with her spouse, Virginia Holmes. Website: http://shirleyglubka.weebly.com/ Online poetry at The Ekphrastic Review here; at 2River View here; at The Ghazal Page here; and at Unlost Journal here and here. Housing Depression Caught between void and abyss, darkness crawls, drapes interior walls; it drags through the cracks of a tenement steeped in despair. Emptiness looms, permeates rooms, it gnaws at the slats of a lusterless flat where sadness consumes. Sorrow calls, thrums down the halls, Why go on drones in tenebrous tones when windows appear. Shadows leave, a welcome reprieve. This tenancy's done, though the countdown's begun; it ticks toward its goal: to hinder light's hold, to room in the gloom, to be the gloom that rooms in this house, never once and for all but forever, where never exists with an ending and never-ending's the mean between void and abyss, between chasm and pit, without end. Jeannie E. Roberts Jeannie E. Roberts lives in an inspiring setting near Chippewa Falls, Wisconsin, where she writes, draws and paints, and often photographs her natural surroundings. She has authored four poetry collections including the most recent The Wingspan of Things (Dancing Girl Press, 2017). She is Poetry Editor of the online literary magazine Halfway Down the Stairs. The Staircase She is shrouded in shadow, prays not to stumble as she wends her way to the top of the stairs. She hums softly day after day, week after week, her nestling voice swallowed by fear, not knowing what waits for her in that tiny room draped in darkness. Maybe her screeches will pierce the silence, maybe nothing. Doesn’t seem to matter anymore. It’s the climb. It’s the knees buckling. It’s knowing she left the water pitcher at the bottom of the steps, and her mother will scold her like a child who treated it as if it were a broken toy. Her mother won’t recall who feeds her, washes her hair brushes her teeth, changes her diaper, bathes her, kisses her gently, listens to her rants, wipes her tears. But her mother will remember the pitcher. Shelly Blankman Shelly Blankman lives in in Columbia, Maryland. She and her husband have two adult sons and now fill their empty nest with three rescue cats and one rescue dog. She has followed a career path in journalism and public relations but her first love has always been poetry. Her work appeared in The Ekphrastic Review as well as other online journals, including Praxis Magazine for Arts and Literature, Visual Verse, Social Justice Poetry, and Poetry Super Highway. Always the Shadow It isn’t the creaking of wood or the musty smell of old oak seeping, rising up that sticks in my throat but the shadow, always the shadow cast on the darkened wall. Each monochrome day I watch her climb those nine wearisome stairs dragging her ragged breath behind her, skirt as loose as her tongue cursing, ranting at shadows, always the dusty shadow cast on the wall. The time for weeping is past but she visits him often believing him to be there at the top of that ninth stair door ajar, jug at the foot a vessel poised to clean grief and wash the shadow, always that deep stained shadow from the wall. Kate Young Kate Young has been passionate about poetry since childhood. She lives with her husband in Kent and having recently retired from infant teaching she has returned to writing. She had some success with poems published in magazines when she was active in Strood poetry group. She now enjoys meeting members from The Poetry Society at her local Stanza group and sharing work with them. Alongside poetry, Kate enjoys art, dance and playing the guitar and her growing collection of ukuleles! The Servant Stairs Up these narrow stairs – the only way servants could rise above the master. No servants here now. The mansion demoted to a boarding house worn to shabby chic – elegant bedrooms, mahogany mantels, outdated plumbing. My view of the back lawn sold me. I went upstairs on moving day – just empty attic rooms with suitcases and Christmas ornaments – but coming down I fought the urge to take the steps two at a time. Now I know why. Every night I hear soft footfalls on the landing, heading up, up, up, then padding back and forth across my ceiling for hours. That first night I peeked out, saw nothing, not even the wash pitcher I tripped over before breakfast. I imagine the ghost of a young scullery maid accustomed to working late. I wish she and I could both get some rest. Alarie Tennille Alarie’s latest poetry book, Waking on the Moon, contains many poems first published by The Ekphrastic Review. Please visit her at alariepoet.com. Up and Down Even with a moment to rest on the landing, Leda needs to take a deep breath. Carrying that heavy ceramic washbasin, even unfilled must be accomplished with care. Mistress loves it. Leda also loves to admire swans swimming in a lake bounded by rose bushes. Often, after she has place bowl on wooden oak stand, after she has set the matching pitcher inside or beside it, laid fresh soap and an ironed linen towel beside it, she imagines she can smell those painted roses, that the swans will come and eat dried bread from her hand. Leda carefully mounts each step and when she has so very carefully and quietly placed that empty bowl, she will dance quickly down the steps to pluck up the pitcher, heavy with cool well water making all ready for her lady’s morning ablutions once that lady chooses to respond to sun’s signal. Tho the bowl and pitcher are works of art, Leda cannot help but wonder as she treks up and down the backstairs in day’s predawn grey, might it not be easier if mistress did as she, Leda did, washing face and hands at the well with two quick pulls of the handle, up and down. Joan Leotta Joan Leotta is storyteller on page and stage. When she is not writing she is often walking the southeastern North Carolina beach--weather permitting. The Staircase First there were the whispers. The clacking of small shoes on wood, occasional sighs. A staircase full of disappointment and teases. The swish of petticoats, muted giggles. Later there were sobs and the sound of skin slapping skin, hate a thick broth of unbreatheable air, cold reaching out to embrace the unwary. No respite, never peace, its need immense. The staircase kept its secrets, barely, until it was loved into forgetting. Rose Mary Boehm A German-born UK national, Rose Mary Boehm lives and works in Lima, Peru. Author of Tangents, a poetry collection published in the UK in 2010/2011, her work has been widely published in US poetry journals (online and print). She was three times winner of the Goodreads monthly competition, a new poetry collection (From the Ruhr to Somewhere Near Dresden 1939-1949 : A Child’s Journey) has been published by Aldrich Press in May 2016, and a new collection (Peru Blues or Lady Gaga Won’t Be Back) has been published (January 2018) by Kelsay Books. What You Leave Awaits You What do you leave at the base of the stairs too heavy or odious to lift? A full chamber pot? The stale water from yesterday’s ewer? Or the nothing that never became anything more? You trudge to your garret to weather the long night. Should dawn come, faithful as any draft horse to duty, you will descend and once more take your burden up. Again to the well—the slosh, the murk, the running clear. You toy with abandonment, but set the jug carefully down. One never knows what one will hanker for. Better something than nothing— even if what awaits is inanimate. Devon Balwit Devon Balwit teaches in Portland, OR. She has seven chapbooks and three collections out or forthcoming, among them: We are Procession, Seismograph (Nixes Mate Books), Risk Being/Complicated (a collaboration with Canadian artist Lorette C. Luzajic); Where You Were Going Never Was (Grey Borders); and Motes at Play in the Halls of Light (Kelsay Books). Her individual poems can be found in The Cincinnati Review, The Carolina Quarterly, The Aeolian Harp Folio, The Free State Review, Rattle, and more. Dawn Treaders Reminders of what’s gone before, each growing shadow seeks the floor like echoes of the previous day; they cling to ceilings, misty-gray, then sliding downward in the hall the balustrades soon reach the wall, continuing, while she’s begun to start a task that’s never done. Though weary, she will start the morn refreshed, because a new day’s born. Each day begins before it starts with those who play these lonely parts. They carry linens to and fro-- the fresh delivered, old ones go-- as dust and cobwebs disappear, the floors well-swept; the corners clear. Disarray’s arrayed again, washbasins filled so all the men and women can resume their day refreshed, and soon be on their way. They wind the clocks so Earth will spin; clean windows, letting sunshine in and us peer out—not seeing them, not noticing each gent or femme who plays their role to keep us whole-- obscure, although that’s not their goal. Integrity and inner strength raise character to fullest length and we’ll see work comes from their soul in moments saved by artist’s coal. Ken Gosse Ken Gosse uses simple language, traditional meter, rhyme, whimsy, and humour in much his poetry. First published in The First Literary Review–East, November, 2016, his poems are also in The Offbeat, Pure Slush, Parody, The Ekphrastic Review, and other publications. Raised in the Chicago suburbs, he and his wife have lived in Arizona over twenty years, always with a herd of cats and dogs underfoot. Mistress of the House She’s tired—this her third trip up the stairs to his sick bed. The pitcher of clean water yet to fetch. Where are his children, his family to take care of him? Do they even know he’s dying? She has yet to make supper for her other boarders. White apron now soiled with his sickness. She will have to go downstairs once more to change, then the kitchen and the heavy pots, the leg of lamb, vegetables to be scrubbed and chucked into the pot. But he will cry out again and up the stairs she must go. She feels like she will go mad half way up, one hand on the rail feet aching and sorrow for him in her soul. Jackie Langetieg Jackie Langetieg is retired and lives in Verona Wisconsin and secretly wishes it were Verona Italy. She lives with her son and two kitties. She is a regular contributor to the Wisconsin Poets’ Calendar, has published poems in small presses such as Bramble, Verse Wisconsin, Wis. Academy of Sciences, Arts, and Letters, and has published two chapbooks and two collections of poetry. She currently is working on a series of stories for a memoir. Dreamwork The mind's backstairs dim and underlit dusty and neglected the servant's way from cellar to attic in an old house The maid in her gray dress no more than a shadow in the background carrying coal and trays of food dusting and polishing everything that shows keeping things neat and presentable- a hinge in the gate between daylight and darkness listening-listening at the master's door for secrets only she will use or keep. Mary McCarthy Mary McCarthy has always been a writer though she spent most of her working life as a Registered Nurse. Her work has appeared in many online and print journals, and she has an e-chapbook, Things I Was Told Not to Think About, available as a free download from Praxis Magazine. Expectant She ascends the stairs To clean, perhaps To offer a bath. But first she knocks Is the lodger within? The hallways Though shadowed Render order Stabilized by unknown Source of light The shining ceramic On the stair below Brings beauty to the scene The ewer sits expectant So much of what we hope for Seems contained therein. Carole Mertz Carole Mertz, an advance reader of prose and poetry at Mom Egg Review, enjoys 20th C. and contemporary visual arts. (She is a proud sister to two visual artists.) Carole has poems and essays at Arc (online), Eclectica, Indiana Voice Journal, Prairie Light Review, Pyrokinection, Quill & Parchment, Voices on the Wind, World Literature Today, and elsewhere. She resides with her husband in Parma, Ohio. Your Ewer on the Landing Left... Your ewer on the landing left reminds us not that we're bereft but rather of how often filled our hearts have been with love instilled by work to which you humbly bent as we were blessed by your ascent to heaven's realm by servitude you selflessly so long pursued. From shadowed harp on rising walls your muted song still heard recalls the smile of your heroic face that greeted death with stoic grace as if so clearly then discerned to be reward so rightly earned. Portly Bard Portly Bard: "Old man. Ekphrasis fan." Just One More Step One more step. That’s it. One more step... ...and I’ll be rid of all filial obligations. Took your extra night-nights like an obedient burden--no resistance. But a schedule relies on clockwork. A 2 a.m. voiding of the bladder is necessary for dry dreams--for maintaining what little respect I have left for your still-inhaling husk. So, why couldn’t you wait? I’m two minutes late and your dignity takes flight--left to strip your bed, and your shivering carcass in the middle of the night. Again. I don’t even mind the fetid laundry, or sponging off what remains of your modest manhood. It’s the broken sleep. The persistent fuzziness--being woken at random hours every evening. My own children barely grown, I am now caretaker to a toddler who once raised me. One step, Dad. That’s it. I forgot to bring the clean chamber pot up from downstairs. Just one more step. Jordan Trethewey Jordan Trethewey is a writer and editor living in Fredericton, New Brunswick, Canada. His work has been featured in many online and print publications, and has been translated in Vietnamese and Farsi. Stairs When you were a wee lass, the three flights of wooden stairs were nothing. You flew down, impatient to be outside. You scampered two at a time up to tell your mam what you’d seen, what the biddies at the market said. The stairs, already old when you were young, wore down. The edges were raw and soft splinters rolled off until one day it was refinished, leaving scoops and dents and pockets. They still creak and crack, the inside edge of the second step of the second floor loudest and weakest of all. Always use the far side of the step, to be safe. By then, your da had long gone, your mam was ill, and you had raised two brothers and three sisters. The youngest brother, married, with children, living with his wife’s parents. Same with your sister Jane. The one closest to your age, Mary, died as a child. Anne, the middle one, lives with you at home with you and your brother Ned, helping care for your mam and taking in laundry and sewing. Anne had a husband too. Worked in the coal mines. Had carrot orange hair, dark circles under his eyes, spoke with a lisp. A narrow, thin frame. Not thin enough to save him being crushed by minecarts when the engine failed and the brakes failed and four carts raced backward into the depths, coal returning to its source. Killed five men, none of whom had seen their twentieth birthday. The light in Anne’s soul went dark. Your man, Leonard, was different. A student at the college, son of a barrister, he had no black stains under his nails or in the creases of his hands. In his turned up trousers, fine waistcoat, and navy-blue blazer he would smoke cigarettes and talk of wondrous peoples and places, of Nietzsche and Russell, India and Asia. He filled your head with words and thoughts and images and stories. Until you told him you were with child. The child, fortunately, never took a breath. A soft, lifeless lump that Leonard never saw, him having been recalled to York by his father. Like your da, you never saw Leonard again, save in your dreams, where he shows you the colours and people of those mysterious places where you will never be. Your brother Ned has less discord with his lot. His world is uncomplicated, he is easy to please. Twelve hour days in the mine aren’t a strain. He accepts what life gives him, sips a pint with the lads on the way home, smiles when you remove his dust caked trousers and boots in the evening. He’s earned this respect, his place as the primary wage earner for the household. But he coughs, like any miner who has lived past thirty years. And though you never spent a day in the mines you have the cough too, or something like it. It is difficult for you to catch your breath. Halfway through each load of laundry you pant shallowly, resting on locked elbows, staring at the soapy washboard, inhaling the steaming lye. Anne refuses to meet your eye. Even now, she pretends you don’t exist, resentful, having to assume your share of the work. The pick ups and returns and all the carrying of the laundry up and down the stairs she must do alone. Standing over the washbasin is all you can do. Ned is more sympathetic, if only because he understands the future less. This is the cough that took your mam to bed, that rendered her incapable of washing, of cooking, of caring for her children. But it’s having its way with you faster. Walking from one room to another is all you can manage. It took years to reduce your mam to a bedridden shell; you are getting there in months. At this rate, join her as an invalid soon you will, then beat her to the finish too, as you did racing her up the stairs as a lass. Old, and worn, chipped, broken and patched, the stairs will live on without you. Glenn Mori Glenn Mori reads and writes prose across as many genres as he can, though he admits to finding some more challenging than others. He is a member of local and online writing groups and is an Editorial Assistant for the online magazine Every Day Fiction, where his fiction was first published. Recently, he was shortlisted for the Federation of BC Writers Literary Award, and Lycan Valley Press Publications will include one of Glenn’s stories in an upcoming anthology. Glenn is still working at transposing his education in music composition into fiction writing. Ceramics The body is a handled cup, a depression with a loop, a donut waking up slut lip shut to topological this/that/want, sweet tea sweet meat sweet me. The body creates lumpnut dip, milk for the limpdick skin of ceramic permanence - spade scrapes shard from earthen comfort. Dilation and curettage change nothing. Essential mapping morphs dust to dust - even porcelain crumbles thus. So I-we-you-they, once patterned he/she in floral cobalt at the rim of some longing gone to whim of cream in a sea of tea, go the way of rough surf in the death of wind. One surface bends to form again, spun loving up from what's left of us. Ferral Willcox Ferral Willcox is a U.S. born poet currently living in Pokhara, Nepal. Ferral's work can be found in Per Contra, Peacock Journal, concis, Calamaro, and elsewhere. She was a featured performer in the Philadelphia Fringe Festival, and is a regular contributor to the Plath Poetry Project. The Old Woman She slowly climbs the stairs, leaving the pitcher behind, her arms piled with fresh linens, washed in the wringer, dried in the sun’s clear gaze, then pressed. They smell like summer though it is November. She turns up the narrow staircase to the tiny apartment where her children and grandchildren sleep during rare visits. It was once a choir balcony--- another apartment matching this across the way, rented out for additional retirement pay. But this is special, her son’s family driving from the city for Thanksgiving. The old woman prepares each bed with hospital corners, bounces a quarter off each before she is satisfied. Then she covers them with chenille bedspreads, bleached so white each bed looks like a drifting snowbank. There are two double beds in the living room and another tucked away beneath the dormer, a tiny bedroom that also holds a white dresser. She will go back downstairs to pick up the pitcher, the one that belonged to her mother, to hold water for the family, so they can wash in the morning. She loves it so. And she shares its small beauty with this distant family, the granddaughters she barely knows, but loves anyway, the pull of her body aching and tired. It is a lot of work, a lot of preparation---cooking, cleaning, ironing. But she does it all without criticism of her alcoholic daughter-in-law, of the bitter son she no longer easily recognizes. That is the way they live, and she will make the best of it. Carefully she pats her twisted bun, pushing tendrils of hair from her face. She will remove her apron and settle downstairs in her apartment, dinner cooking in the oven, her knitting calling her attention. When they arrive at last, she will wake her husband from his nap, lead the family upstairs, careful that her feet fall on the carpeted runner protecting the finish of the many steps it takes to climb to the loft. Virginia Chase Sutton Virginia Chase Sutton's chapbook, Down River, was published last fall. Her second book, What Brings You to Del Amo, was the winner of the Samuel French Morse Poetry Prize, and is being re-issued by Doubleback Books. Embellishments was her first book and Of a Transient Nature was her third. Seven times nominated for the Pushcart Prize, her poems have won the Untermeyer Scholarship in Poetry from Bread Loaf, the Allen Ginsberg Poetry Award, and the National Poet Hunt. Poems have appeared in The Paris Review, Ploughshares, Poet Lore, Comstock Review, and the Peacock Journal, among many literary publications, journals, and anthologies. She lives in Tempe, Arizona with her husband. What Goes Around Comes Around You perch on high but nine steps away. Look me in the eye. Make me shiver cold like water in the ewer. I taste your silence screaming through the ether resonating, reverberating against the false ceiling open to the elements. You beckon me to join by the lisp of your tongue step after step closer to your door nearer to my death. Each step my admission of some heinous crime against society on earth each nearer to purgatory each hotter than fire. You magnetise my soul, my heart, my mind drawing me up closer with nowhere else to go. Nothing else matters. How I long to be the child free of incumbence devoid of my trespass unattached to guilt unable to condemn. You grasp me in your vice as you disappear off through the ethereal taking me in my sorrow of decades long ago. I cry for those I have missed, not even seen. Those who are not born and those who I took for vengeance post-pain. You perch on high but nine lives away. Take me in the heart. Make me shiver cold coming around too late. Alun Robert Born in Scotland of Irish lineage, Alun Robert is a prolific creator of lyrical verse achieving success in poetry competitions in Europe and America. He has featured in international literary magazines, anthologies and on the web. His ekphrastic poems have appeared in The Ekphrastic Review and Nine Muses Poetry. Mark Rothko Poem

Such things are cakes or confectionary. Lozenges leave me marooned in magenta and maroon. The smell of this white cube, smell of the cerebellum too. Light subdued makes the heart sound, go Stendhal all of a sudden. To me this canvas is a Vimto ice-cube. I catch puce. The blurb’s seen on the back of a can. If licked that surface would taste of sugar, strips of colour or cakes (they recur) as if placed in Patisserie Valerie. Iphones click while I contemplate as if culture is a thing to consume. The French mill around me. I can’t speak Italian. They wear backpacks or look smart in suits and ties. Faces aghast, stupefied. Slowed attention spans. Or lovers immersed, hand-in-hand. Nine canvases in total. The four seasons. The Seagram murals hang like meat or beef hangs on hooks. A perimeter fence stops me from seeing the paint too close. I cross the line. Alarms go off. Rothko himself would disapprove. Everything made dim and church-like. The artist was against graven images. Seeing the paintings like this it’s the scale that surprises. The girl I’m with wanders off to muse a Bridget Riley. I refer to her in terms of gran mal seizures. For now I gorge on these. And this bloodless surface too clean would taste of germalene. As foreign tongues guzzle the spectacle, I go to a truffle. I go further. If these are windows they’re windows on the hereafter. Though so much is unflashing photography. Are these suicide notes? I have an urge to steal one and hide it under a massive coat. Or I want to unleash on this surface a machete. I want the aura to be cut through. There are no signs of Mary. This isn’t a nave. And again I crave a knife and a cake. Patrick Wright Patrick Wright has a poetry pamphlet, Nullaby, and forthcoming collection published by Eyewear. His poems have appeared in several magazines, including Agenda, Wasafiri, The Reader, London Magazine, Poetry Quarterly, Ink, Sweat and Tears,and Iota. His poem ‘The End’ was recently included in The Best New British and Irish Poets Anthology 2018, judged by Maggie Smith. He has also been shortlisted for the Bridport Prize. He is studying towards a PhD on ekphrastic responses to dark or near-black paintings, and he works as a Lecturer at The Open University where he teaches Creative Writing. Dry Grass The dry grass smells like baked bread in the sun. The mountains have snow, also pine, and sagebrush. Clouds purple the ground in shadow, and sage brushes my arm. Does the moment stop thoughts? I remember walking through Idaho and Eastern Oregon, or even in the low chaparral at the base of Mt. Diablo in childhood, seeing or smelling distant snow and the moment could stop thoughts. The sun hurts my eyes, and the soil is gritty and rhythmic to walk on. I remember walking through sage brush, and the gristly scratch of nettle, and trying to make my thoughts stop. The openness of the land and the beauty of distant snow, the sun on my back. I remember walking through a farm in Idaho and watching lightening clouds gather over the foothills, hearing crickets, and then the thunder came and crickets stopped. The rain started, and the smell of dry sandy soil and wet sage. I remember the rain on my face, and the coolness of rain soothed the mosquito bites covering my legs and arms. I worked with horses in Idaho, clicking my tongue and offering rewards for wanted behaviour. I remember the smell of horses, horse cookies, soaked beet pulp, bean soup from a can for me, the sound of rain on the barn roof and the flies even seemed to get still and listen. The horses breathed and stomped. I remember walking through sage brush leading a horse, the flick of his tail, the heavy saddle groaning like an old house. I remember how my thoughts could stop and rise by the power of longing, and how much I looked for that feeling in dry open places. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|