|

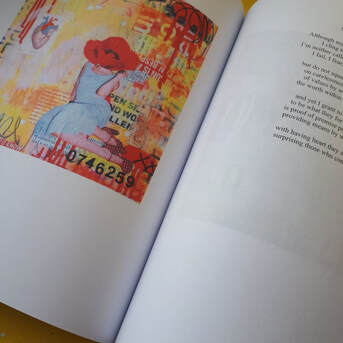

A Lemon Light Embrace We are wired for connection. We walk on living land. Soil in our veins, butterfly wings painting our palms with heart line and life line. The green of every living thing exists in the grass beneath our feet. Life swims to our fingertips. We reach out to touch robin’s egg blue, in love with the energy of air, the pulsing rush of lifeblood that comes with each savored breath. Walk gently in meadows, leave no mark on your life’s hike, wash sorrow from the terrain by removing bottles, wrappers, and the debris of modern living. Cocoon yourself in moments, in the rise and fall of nature’s chest that swells and falls just to release oxygen for us all. Hold close each and every tiny living thing. Offer your hand like a mountain peak, like a tree branch, like a true offering of refuge. Be the safe place for nature to flourish, as you have been nurtured, embraced by a lemon-hued light. Cristina M. R. Norcross Cristina M. R. Norcross lives in Wisconsin with her husband and two sons. She loves to sip and savor nature in her backyard which is home to sandhill cranes and owls. She creates in several different mediums, including wire-wrapped beaded jewelry. Cristina is the editor of Blue Heron Review, author of nine poetry collections, a multiple Pushcart Prize nominee, and an Eric Hoffer Book Award nominee. Her most recent collection is The Sound of a Collective Pulse (Kelsay Books, 2021). Her work appears in numerous journals and anthologies. She facilitates a writing prompt group and hosts open mic readings. www.cristinanorcross.com Danelle Rivas was educated and trained at Pratt Institute and NYU at a master’s level which provided the foundation for her work, but it has been relentless, creative inquiry that has driven her career. Danelle has studied at The Art Students League (NYC), The Brooklyn Museum Art School, and The School of Visual Arts (NYC). She holds an M.A. in Studio Art from NYU and a B.F.A. from Pratt Institute. She is a member of: ABLA (Art by Latina Artists), Art Lanow, Valour Art, DCA Slide Registry, and ArtSlant Worldwide. Her work has been featured in numerous art exhibits.

0 Comments

Deadline for the Art of Tarot contest is in a few days- midnight on November 23, 2022.

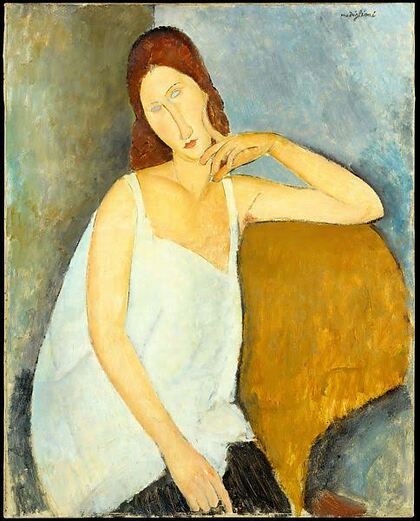

There won't be an extension, so polish up what you've got and get those goodies in to us! Refresh yourself on the rules and instructions, here. Our judges Riham Adly and Roula-Maria Dib are very eager to see what you have conjured. On My Terms I rarely make a sale, but still I strike my mark in artists’ circles. Everyone knows I drink and smoke hashish. Sometimes I like stripping off my clothes at parties. I chose to leave behind my bourgeois youth; the route to real art is disorder and defiance. Although I am unwell and destitute, I seek no help and I reject alliance with any group or style. Still, I’m tied to sweet and gentle Jeanne; she’s expecting soon, and we’re engaged. She’s terrified TB is claiming me. But self-protecting’s not my game. Intense brevity means far more than dull longevity. Barbara Lydecker Crane This poem is from the author's upcoming collection, You Will Remember Me, Able Muse Press. Barbara Lydecker Crane, twice a Rattle Poetry Prize finalist, has received several awards for her sonnets. Her poems have appeared in The Ekphrastic Review, First Things, Light, Measure, THINK, among others. Her fourth collection, You Will Remember Me, sonnets about artists and portrait paintings, will be published by Able Muse Press. More at The Ekphrastic Review by Barbara Lydecker Crane The Blue Hour House of Cards Reflection (nominated for the Pushcart Prize) Girl with Shuttlecock Lately, my mind has been preoccupied with children at play. On my walks in the park, I find myself sitting down to watch the boy sailing his small boat on the pond, the young girl following her hoop, two children touching heads while crouched over their spinning top. There is in their concentration something that I recognize. It reminds me of that stillness, the rapture produced by an object that can be found in a still life. There is no world, there is no observer – only the spinning top, the turning wheel, the running legs... And something else as well – after Marguerite-Agnès’ death – my thoughts and my eyes are drawn all too easily to young girls. Here is the seven-year-old, the twelve-year old that she will never be, that I will never know. Mourning colours my appreciation of childhood’s innocence, its obliviousness of death. Back in my studio I think of the many games of childhood that allow children a reprieve of knowing, that provide provisional shelter from the world of adults. I well remember the pleasure of blowing soap bubbles through a straw, the slight soapiness in the mouth and the delicate interplay of my breath trying to expand the bubble beyond what seems possible. To catch that, the moment just before the bubble bursts, as we know it will, to hold that tension for one more fraction of a second, would be to arrest time. I find myself becoming obsessed with catching something of this on canvas and find, as so often, that one attempt will not do. The concentration of the boy blowing the bubble is not like the one of the boy building the house of cards. He has just put his studies behind him, is still wearing his school uniform, when he pulls out his deck of cards and builds with his mind, his hands and all of his acquired knowledge and skill. Nor is that concentration the same as the inwardness, the self-sufficiency I try to convey of the young girl poised on the threshold between childhood and young womanhood. Here on my canvas, she steps out of the warm brown tones of the background, all gravity and grace. Her dress, an important part of who she is, a foam of opaque white that gathers the light and draws the eye to the white flounce of her sleeve on the velvety brown bodice that gently and with great simplicity underscores her essential innocence. The blue ribbon tied at the waist, as if in haste, holds a pair of scissors and a small red pincushion like a tradesman’s insignia, an emblem of her industry. But now, at this moment, work is forgotten, she is gripping the racket firmly in her right hand, while her left, resting on the wooden finial of the chair, gently holds the shuttlecock. There is a delicate pearl necklace around her throat, a small golden earring in her ear, her hair is tied at the back with a diaphanous yellow ribbon, an embroidered, lace-edged cap sits on her powdered curls. She could be a younger version of the cocottes one sees at court – were it not for her face, the far-off look in her blue eye, its blue matched by one of the feathers of the shuttlecock, and that child-like profile, as yet unaware of its impact on the world. Notice the faint bloom that has risen in her cheeks, as if in anticipation of the game... She has stood patiently for me again and again, portraying in her nature something of what I try to put on the canvas. I feel I need to honour that part of her, her vulnerability and beauty. When finally, all the blues echo each other in deep sympathy, when the delicate pinks take the eye from the back of the feather to the rose shadow on her décolleté to her neck and cheeks, up to the tiny red flowers embroidered on her cap and when the delicate balance of posture and chair form a triangle, I step back. I too want to hold the moment; the moment when in great harmony, subject and painter are one. Barbara Ponomareff This piece is an excerpt from the author's novella, A Minor Genre: A Life of Jean Siméon Chardin, Artichoke, Volume 14 (2) and 14 (3), Summer and Winter 2002. Barbara Ponomareff lives in southern Ontario, Canada. By profession a child psychotherapist, she has been fortunate to be able to pursue her lifelong interest in literature, art and psychology since her retirement. The first of her two novels dealt with a possible life of the painter J. S. Chardin. Her short stories, memoirs and poetry have appeared in Descant, (EX)cite, Precipice and various other literary magazines and anthologies. She has contributed to The Ekphrastic Review on numerous occasions and was delighted to win one of the recent flash story contests. More from Barbara in The Ekphrastic Review: Stepping on the Throat of Their Song (winner in flash fiction category, Birds Contest) In Search of Albrecht Durer (poetry) With Pearls in My Hair (story) Witnesses In this winter of woe, I went looking for hope and found it in the purple pansy’s fight for life, in the maple leaf’s ice crystals, illuminated by the sun. I discovered it in the spider’s long web, the cricket’s loud chirp, the bluebell’s sweet swansong. I saw it in the ravens’ twice-daily care package to the prophet of old and in today’s experimental drug designed for disease difficult and rare, rare like the white peacock in the grasslands of Australia. I witnessed it in the rhythm of the rain, in the salmon’s epic journey to spawn and die, in strangers’ fist and elbow bumps, in their good wishes. And I heard it in the instructions at a Bethany burial site over two thousand years ago-- unbind him and let him loose. Jo Taylor Jo Taylor is a retired, 35-year English teacher from Georgia. Her favourite genre to teach high school students was poetry, and today she dedicates more time to writing it. In 2021 she published her first collection of poems, Strange Fire. She enjoys morning walks, playing with her two grandsons, ages four and seven, and collecting and reading cookbooks. THROWBACK THURSDAY: Selections by Alarie Tennille SMALL TASTES THAT WILL MAKE YOU CRAVE MORE Before the meal, fine restaurants often present you with an amuse bouche, French for “mouth amusement.” It’s a small, complimentary appetizer, often just a single bit, so wonderful you want to order everything on the menu…or maybe that’s just me. I delight in short poems. They don’t have to be haiku short, but they always wow me by accomplishing so much with an economy of words. I could read them all day. Here are a few short masterpieces I selected from previous Octobers and Novembers at The Ekphrastic Review. I hope they’ll make you want to look around at your old favorites and keep coming back for more. Bon appetite! I’ll also challenge you with a writing prompt. Revisit a poem or short fiction of your own that’s over 20 lines long and rewrite your thoughts in half the words. Maybe it should start three or four stanzas later. Maybe you tacked on a wrap up that wasn’t needed. Experiment. Revision is one of the best ways to get around writer’s block. ** I am the promise you didn't keep, by Sarah Russell https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/the-persistence-of-memory-by-luis-cuauhtemoc-berriozabal Sarah Russell captures the secret to brevity: not filling in what should be left open. ** Rumblings of the Earth, by Neil Ellman https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/rumblings-of-the-earth-by-neil-ellman Look how much we can learn from the masters. Neil echoes the message of Sarah Russell. We don’t need or shouldn’t need others to tell us what we will become or what our art means. ** The Little Girl in the Painting, by Jean L. Kreiling https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/the-little-girl-in-the-painting-by-jean-l-kreiling It pays to revisit poems you’ve enjoyed from the past. Initially, I enjoyed how Kreiling portrayed the thoughts of a child. Her brevity reflects the little girl’s eagerness to slip away. Only on rereading did I realize this was a rondel, a 13-line French verse form that we don’t come across every day. ** When Alice Became the Rabbit, by Cyndi MacMillan https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/when-alice-became-the-rabbit-by-cyndi-macmillan I laugh at the author’s audacity in contradicting Lewis Carroll. Here’s another good writing exercise: set some well-known story or legend on its head. Since most legends and myths have been passed along by men, it’s easy for a feminist to say, “Now wait a minute!” Editor's Note: This story was nominated for Best Microfiction, and was selected by the Best Microfiction series for publication in their annual award anthology! ** Wind-Swirl, by Joann Grisetti https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/wind-swirl-by-joann-grisetti I suppose it’s obvious by now that I gravitate to the art created by our editor, Lorette C. Luzajic. By using abstractions and leaving empty space, she invites writers to tie a few juicy details from the canvas into their own thoughts. Voilá! A collaboration that is something new. ** The Persistence of Memory, by Luis Cuauhtémoc Berriozábal https://www.ekphrastic.net/the-ekphrastic-review/the-persistence-of-memory-by-luis-cuauhtemoc-berriozabal I love the author’s certainty: Dali knew “Those clocks/ could not tell time at all.” That’s the fun of being an artist or poet. We get to play by our own rules. Call for Throwback Thursday Selections!

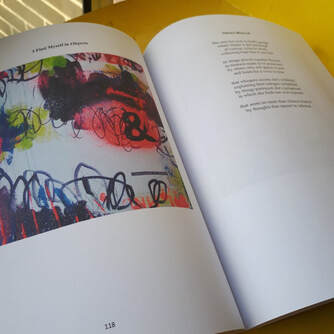

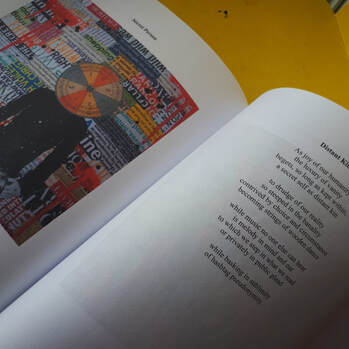

Be a guest editor for a Throwback Thursday! We occasionally post this feature on Thursdays and would love to do so more often. Pick around 10 favourite or random posts from the archives of The Ekphrastic Review. Use the format you see above: title, name of author, a sentence or two about your choice, or a pulled line from the work, and the link. Include a bio and if you wish, a note to readers about the Review, your relationship to the journal, ekphrastic writing in general, or any other relevant subject. Put THROWBACK THURSDAYS in the subject line and send to theekphrasticreview@gmail.com. You sharing your favourites or making a random selection for discovery helps writers get readers. We have over 5000 pieces of ekphrastic literature on this site and at least 1000 different writers. Show us the ones that moved you over the years. Along with your picks, send a vintage photo of yourself, too! Let's have fun with this! On the Aerodynamics of Angels Draped in weighty earth-tones, DaVinci’s Gabriel kneels in this walled garden, casts a deep shadow across the lawn of blooming flowers. Straight from heaven, he delivers his message to Mary, who turns from her book, welcomes him. Not at all the usual floating illumination, this angel is grounded. The scientist, so exact about mechanical workings of everything, leaves his angel’s celestial wings unfit to hoist his heft even an inch into air. Flying, Gabriel is equipped to soar with a single wingstroke, to all places, all at once, but descended to earth, bearing worldly news, he’s unmistakably, at this moment, one of us. Ann Taylor Ann Taylor has written two books on college composition, academic and free-lance essays, and a collection of personal essays, Watching Birds: Reflections on the Wing. Her first poetry book, The River Within, won first prize in the 2011 Cathlamet Poetry competition at Ravenna Press. A chapbook, Bound Each to Each, was published in 2013. Her collection, Héloïse and Abélard: the Exquisite Truth, published in 2018, is based on the twelfth-century story of their lives, and her most recent collection,Sortings, was published by Dos Madres Press, in June of 2020. She is currently at work on a new collection of poems, called Taking Care. Harboured The sloop is moored now, sails down and rippled like the bay, rocking herself to sleep, smelling of fish and salt and musk. Age and good whiskey let you hear the sighs of boats when they’re alone, freed from the clanks and groans of setting sail. Old boats prefer the gentle swells near shore, I think, clouds flirting with the moon, wisps of wind riffling the water. I pat her wooden hull, dull in places, needing varnish. Me too, I say to her. Me too. Sarah Russell Sarah Russell’s poetry and fiction have been published in Rattle, Misfit Magazine, Third Wednesday, The Ekphrastic Review and many other journals and anthologies. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee. She has two poetry collections published by Kelsay Books, I lost summer somewhere and Today and Other Seasons. Her novella The Ballerina Swan Lake Mobile Homes Country Club Motel will be published in Fall, 2022 by Running Wild Press. She blogs at SarahRussellPoetry.net. This past summer, an ekphrastic collaboration between Portly Bard and Lorette C. Luzajic came together as a full colour collection of visual artwork and poetry. The project contains a creative dialogue between them about ekphrasis, art history, and writing; an essay responding to Lorette's body of mixed media works, and over 100 sonnets, responding to Lorette's collage paintings. Below are two interviews between the artists. Lorette C. Luzajic Interviews Portly Bard Lorette C. Luzajic: You have a very broad appreciation for art styles. Even so, since you are a writer who is unusually faithful to traditional forms, your attraction to my raw, urban, surreal, pop and abstract art is a surprise. What happened here? Portly Bard: Truly novel creativity fascinates me, especially when it clearly springs from intensive interest in the tradition it expands. Beneath your aggressive post-modern cultural immediacy, I found ingenious exploration of the human condition and an appealing legacy of influence. And your haunting poet's heart always seemed present. Even where abstraction was dominant, I always sensed intent and meaning lurking -- with assembly required. It was that thoughtfulness, I think, that made me connect so readily with what you do. I actually bumped into your amazing art as I was trying to research your writing to see if my work had any hope of catching your editorial eye at The Ekphrastic Review. As a traditional, mostly short form poet, I was also immediately taken with the very challenging small size of your signature square canvas and what it was forcing my eyes and mind to do while echoes of rumbling meaning got clearer and clearer as I got nearer and nearer. The fact that what seemed like contemporary looking decor from a distance could dissolve, as one approached, into curiously eclectic, cleverly titled contemplative juxtaposition was mind bending. I was hooked. Lorette C. Luzajic: How did it come about that you wrote an entire book’s worth of sonnets about my work? Did this evolve spontaneously? Did you write one and then another, and find yourself at a few dozen? What drove you to keep going and why? Portly Bard: The effort sprang from the success and failure of my early submissions to The Exphrastic Review. For all the selfless effort you were putting in there, I thought more of your work should appear on those pages. I first submitted your stunning, elegantly simple Chrysanthemum Queen. I have long had a passion for the equally simple elegance of the diminished iambic tetrameter couplet sonnet, and it seemed to be perfect for my notion that you had inadvertently done self portraiture. When you agreed to publish the resulting "Self Portrait Seen in Floral Queen," and when it drew surprisingly positive reaction, I thought I might be on to something. I responded by trying to push my luck with your One Apple on Top, another very simple but very powerful image. When you also agreed to publish "You're the Apple of My Eyes," I began thinking your art could perhaps become a very regular feature on your site or perhaps have its own permanent place there. But when that image and verse got almost no reaction from readers and fellow poets, I realized that my first effort was a rare exception. Continuing to submit such work for publication was clearly not going to help your cause appreciably. Fascination with your small works still constantly nagged me, but by that time, I had also become intrigued with the TER biweekly challenges and I was trying to tackle regular submissions based on other artists. I kept wondering, though, whether I could handle your more complex works in the same diminished sonnet form. And since you personally seemed to enjoy both of the first two efforts, I began to think a publish-me-not bouquet, maybe a dozen or so of such verses, would be the perfect way to thank you for all you were doing with The Ekphrastic Review, which I thought was remarkably adventurous and advantageous to so many. The challenge of reducing your work to my beloved single thought form was daunting, and that kept me chipping away at it. I soon had about a dozen and a half drafts, and I began to believe the gift idea was actually going to be worthy. Yet it seemed like even a dozen finished works would no longer be nearly enough. I thought if I just kept going, the muse would let me know when the collection was big enough -- and good enough -- to send it to you. When it began to look like I was going to get to at least fifty, though, I started thinking that binding them into a book might be a way my gift could actually serve a useful purpose in your journey. My objective then became something akin to portraiture -- a representative, revealing sample of your signature works, a "gallery" big enough for people to lose themselves -- and find themselves -- in. And that also meant trying to keep it as current as I could with your ongoing production until it became actionable. It just felt to me as time went on that a useful book was going to need at least a hundred images if the muse could sustain my momentum. When I simply could not fit some of the verses into my form of choice, I realized that more like a hundred and twenty drafts would have to be the goal. And when we finally went to a layout that could also accept the non-conforming verses, that's about how many I had done. Even so, though, I never did get to the truly representative sample I had envisioned. And that troubled me, but I was satisfied that we had enough to make going to press viable. The similarity I saw in the constraints we each took on and the sheer joy of our very rare ekphrastic juxtaposition kept me at the grindstone. It was certainly not effortless, but each of the images led io a verse that was rewarding in its own way. The richness of your work took me as far as I got for the book, and I'm still going. Most of my more revent effort, however, has been more focused on your equally intriguing larger works. Lorette C. Luzajic: What attracts you to traditional poetry? Do you ever experiment with other traditional forms or modern forms? How did you choose the sonnet, and why did you stay with it? Portly Bard: I was raised on traditional poetry and its song lyric equivalent. I was schooled in it by amazing teachers and professors. I came to understand that poetry was poetry because it made the meaningful memorable or the memorable meaningful. I was taught to respect form, metre, and rhyme as poetry's oral tradition roots and as the strengths of its performance potential. I knew the meaningful and memorable criteria could cerainly be met without form, metre, and rhyme elements, but I also knew the task became extremely difficult. Yet I knew as well that those three requirements would tend to compel my creativity, not constrain it, very much like the four small equal sides of your signature art canvas. And they would naturally move me toward meaningfulness and memorableness. They wouldn't necessarily guarantee getting there, but the better they were used, the closer a clever idea would get. My allegiance to form, metre, and rhyme therefore became unwaivering. I have, though, also dabbled in traditional Haiku, which involves form but requires neither metre nor rhyme. Flash fiction in its briefest forms also tempts me, but time is difficult to find for strengthening the mindset and the tools it requires. All that said, well done ekphrastic writing of all sorts appeals to me as a reader, whether I consider it poetry or not. I have always loved the iambic tetrameter couplet sonnet because it seems to be the upper limit of deliberately small form and length in which a single, truly memorable and meaningful point can be made and supported. When you write them you can recite them That's poetry's acid test. And it's what your signature works seem to demand. I in fact use that form for nearly all of my ekphrasis. I try to make a single, powerful point that is dependent on seeing the art first. And one that sends the reader back to the art immediately for a closer look. Expression limited to 112 syllables was simply as close as I could reasonably come to matching the visual challenge of your often complexly executed twelve inch square canvas. But occasionally, it just didn't work well enough, and I opted for a slightly different form or a somewhat longer one. My first allegiance is to the art, not the poetic form. And that's been the case with all my ekphrasis. If the small sonnet just doesn't work, I opt for rhyme and metre form that is appropriately longer or shorter. And far more rarely, Haiku seems ideal, but I have yet to use it for your works. I enjoy the lower limits of small, single thought expression too. Though extremely challenging, ekphrasis in couplet, quattrain, and particularly limerick forms can also be very powerful. Though I have not used it much for ekphrasis yet, the limerick form (with all its metrical variations) is also one of my passions. It can become the perfect miniature factoid, story, humorous bit, truism, or classic ode. And it can be seamlessly linked in an expository or narrative chain. But your work, far more often than not, is simply ideally suited to the compact sonnet. Lorette C. Luzajic: Tell us about your interests in art history and your literary tastes. When and how did you discover joy in reading or writing ekphrastic works? Portly Bard: As a very long ago liberal arts student, I was compelled to appreciate art history and the philosophy of art -- but neither required coercion. So I was forcibly but blissfully blessed with a "big picture" understanding of visual art's cultural and philosophical evolution. And I have since developed a reasonable grasp of its global market and vertical national industry traditions. I am not, however, an avid student of any particular place, period, or school of thought. I enjoy researching individual works and artists that evoke my muse, so the last four years of investigating your bi-weekly ekphrastic challenges have been an enormous joy to me. And so has reading The Ekphrastic Review every day and following major art news stories on the Internet. When it comes to visual art, I am most intrigued by unique craftsmanship, preservation of history, and poetically evoked thought. As for writing, I appreciate good work of all sorts but I was never much of a novel reader once I put the obligatory classics behind me. Classic short stories, however, still fascinate me, and I like to read the sort of poetry I write, both returning to the masters and exploring the work of fellow pupils. Unfortunately, writing and keeping up with the world leave little time and inclination to savor modern literature. But I do enjoy reading ekphrastic work of all sorts, especially your challenges where the observation, thought, and technique of multiple writers take on the same storied object. I was first exposed to ekpkrastic writing in that now very distant seeming pursuit of my liberal arts education, and I actually dabbled in it on rare occasions thereafter, but I owe the passion I have developed for it to your journal, The Ekphrastic Review. Four years ago, your flagship instantly made ekphrasis an enduring fascination. Lorette C. Luzajic: What are your hopes for this particular project? How have your intentions, hopes, and expectations for this project evolved? What do you want people to take away from your poetry in response to my visual artwork? Portly Bard: I hope we have created something that will serve your journey well. I want people to appreciate all you do, and I want that to make good things happen for you. I want our readers to look at your work again as soon as the last line of my verse rolls past them. I want them seeing far more clearly the thought, the ingenuity, the human sensitivity, the cultural urgency, and the respected influence of your craft's history that you so carefully layer. I want them to keep looking until their own thoughts strike them. I want those thoughts to make them realize they ought to know more about you. And that they ought to come back to your work again and again. That's what truly appreciating it requires. I originally imagined the book would be a simple, speaks-for-itself ekphrastic gallery of your signature square works. Then, for a fleeting moment, I envisioned it morphing into an ekphrastic textbook of sorts by incorporating an essay I have long pondered publishing. Ultimately, though, I dismissed that idea, realizing the book needed instead to incorporate your voice and emulate your art, to engage our curious juxtaposition in a layered set of conversations ending in the art-to-art gallery. The insights into you, under the banner of our title, would be many, varied, and spread throughout those conversations, requiring precisely the same sort of attention to detail your art requires. I like to think of the book now as an assembly-required portrait. In addition to incorpoating your voice, you wound up doing two things that made our emulation very special. First, you found time to reverse the ekphrasis process by visually interpreting two of my works, including the title (and final) verse in the gallery. Then -- at the eleventh hour -- you added the ingenious front and back covers that literally turned the book into art on the shelf. That was a remarkable touch. As the book evolved, I kept wanting it to be a way I could say thank you for all the ways you have found to touch people's lives -- as an artist, a writer, an editor, an educator, a colleague, a mentor, and a sweat equity philanthropist. In my wildest dreams, I wanted it to generate money to support The Ephrastic Review and to heighten awareness of visual art as a global cultural legacy precariously supported by very hard working talented people, often at great personal sacrifice. More realistically, though, I simply hoped the original intent would be served, that it would indeed become a useful resource for you. I hope it helps convince people to comission your work, to acquire your art, to license the use of your art, to invite you to teach, to invite you to be a symposium voice, to participate in your workshops, to buy the ekphrastic resources you have curated, and to submit work and comments to the daily page, the challenges, and the contests of The Ekphrastic Review. Your journal has become a remarkable gallery of global art history and contemporary artistic aspiration. It is a particularly stunning tribute to the long but little known history of female visual artists. And it is a creative writing resource like no other. Portly Bard interviews Lorette C. Luzajic Portly Bard: For the front cover of the book, we originally planned to use our last image, your visual interpretation of my final (and title) poem. As we were finalizing the manuscript for publication, however, you decided instead to borrow a bit from that image digitally and essentially go about proving that someone could indeed very well tell our book by its cover. The ingenious result speaks magically to my experience with your art and to the very thoughtful character of your creativity that can often seem deceptively spontaneous. What was the thought process that got you to the idea for the front-to-back cover at the eleventh hour and then through the iterations required to be satisfied with your work? Lorette C. Luzajic: My work is often as spontaneous and impulsive as it seems, Portly. I appreciate that you enjoy the cover so much, but the transformation is simply a result of a problem- the square shape of the image did not work to my aesthetic satisfaction in the profile rectangle of a book cover. Perhaps what they say about necessity being the mother of invention is often behind improvisation that leads someplace interesting. In working on the cover design, I simply felt at the final hour that I didn’t care for the design using the artwork as a square. But changing the imagery to something else was not suitable- the image was important to the cover because it was symbolic of the project as a whole. So I just started playing around with the elements inside the artwork, freeing them from the constraint of the square. I moved them around until I felt that it worked. Portly Bard: Coming from someone who describes her philosophical inclination as "post, post, post modern," your tolerance of my brief, traditional poetry teeters on the brink of unbelievable. Your willingness to do reverse ekphrasis on my verses is even more stunning. You did two for the book. The one that appears in our "primer" seemed to come very easily, but our title (and final) image required a number of iterations. How did "imagizing" my work, particularly the title verse, affect your creative approach to the task? Lorette C. Luzajic: My weakness and my strength has always been that I am interested in everything. My tastes are exponential. Some may be surprised to learn that I love 17th century Netherlandish still life as much as I love neoexpressionist art like Jean Michel Basquiat, but it becomes very apparent quickly that my work, whether written or visual, is a result of consuming voraciously from many tables. If once upon a time, I was hoping for a place to land, now I embrace my disparate passions and try to infect everyone else through my art, editorial persuasion, and teaching. It has always been this way inside my psyche. My palate longs for the whole world as much as does my palette! I adore Korean and Ethiopian cuisine as much as Italian or Greek. In music, I find transcendence in electronic trance music, in delta blues, in classical, in pop music, and in old time rock n roll. Collage is a place where I can gleefully display the deliciousness I find in contrasts, in juxtaposing parts that supposedly don’t go together. I take absolute delight in unexpected contrasts and juxtapositions. Your work is astonishing to a person who is all over the map. The focus and constraint that a sonnet practice demands is something I envy. Approaching your poetry with my art was a very similar process for me to the way I approach art with my poetry. I spend some time with it, procrastinate a lot and do other tasks or projects instead, all the while consciously and unconsciously incubating impressions, gathering elements, then something comes together in a burst of sorts. If it works, I leave some space and revisit it for balance and breadth. If it doesn’t work, I pull it out time to time, then put it away, then do it again until I give up, or find the spark that pulls it into place. I work very much at impulse and intuition and follow any idea or image where it leads me. Sometimes the finished result has very little to do with the original inspiration, and sometimes it is profoundly intertwined. Portly Bard: If we had bound our handsome hardcover version with a bookmark ribbon, where would it be placed in your personal copy and why? Lorette C. Luzajic: As much as I admire this impressive body of poetry, each one a window into my own imagination, through my artwork, as well as a window into your own heart and mind, the opening essay is my treasure from you. It blows me away that someone could see through the wild barrage of imagery I produce, and find the words I don’t have myself to explain what it’s all about. If I had to pick a favourite poem, perhaps it would be “Keep Going,” inspired by the piece When You’re Going Through Hell, Keep Going. In this work, my borrowed muse was Sir Winston Churchill. This complex, larger than life character who was so pivotal in the freedom we enjoy also blundered terribly and was privately plagued by every error. He didn’t let his anxieties and missteps imprison him. Instead, he studied voraciously, wrote ten million words of history (give or take), and took up painting to manage his mercurial moods. And a little bit of whiskey. I love how your poetry boils this all down into a few words, to the essence of what it means to keep going. Portly Bard: You have recently launched a Tarot ekphrastic prompt booklet and contest, and you have often shared the tale of cementing your self-confident artistic ambition by successfully piecing together Tarot card archetypes as a college student. I allude to that pivotal event at your work in "Fortune Teller." How would you react to a biographer suggesting your "signature squares" are the iconic remnants of that seminal moment? Lorette C. Luzajic: As my Dad taught me, God has many ways of showing up. School was all about getting organized and getting my life together, but I was floundering badly. In those years, I was in the deep end, running from trauma and dealing with profound mental illness without any understanding of it yet. The gravity of graduating, which for me at the time was incredibly difficult and exhausting, and knowing I could not do the work I had taken out a lifetime of loans to learn to do, was monumental. Although things didn’t get better anytime soon, my path changed direction and that would ultimately be important. I took a rest in hopes of getting a grip, and during that time decided to learn about Tarot art and symbolism. The best way to do that was to make my own cards, I thought, and immersed myself in a stack of magazines with scissors. I became intimate with the archetypes, symbolism, psychology, and imagery of Tarot, but I also created a cohesive body of collage works, all 78 cards. I discovered there was enormous release as well as learning involved in creating artwork, and I also found a language of symbols that would prove helpful in my journey. Although I was dazzled at the time by hope of magic, it was the psychological tool of symbolism and the chance at organizing and expressing my ideas that later proved most valuable. It was also about my own lifelong passion for art history finding a way that would come together- the Tarot collages were a portal to how collage would eventually bring everything disparate into my hands. I never stopped creating art from that moment. I let the momentum build. It took me through some wild rides, through life and death and unimaginable chaos. I kept writing, I kept making art, and slowly but surely, everything else fell away. Portly Bard: I have hoped from the beginning of our effort that the book would become a useful resource for your creative journey. You invested a great deal of time and energy in our effort knowing that such books tend to generate very little revenue. How will you put what we have done to use and what do you expect the dividends to be? Lorette C. Luzajic: I learned a long time ago that the things that bring me the most profound pleasure and meaning will bring the same to a few others, and that is the end of it. If I required a massive audience or millions, playing the lottery would be a better game plan, among others. I had to come to terms with that once upon a time, but because my love of art and literature was so intense so early on, it was always more important than numbers. I deeply desire that the writers I work with and the artists I am moved by find a wide audience, so that the important witness and mystery they ponder and reveal can impact more people. I believe quite literally that the arts are where we can understand what it means to be created in the image of God. Creating is a divine gift. Our imaginations are limitless, but they actually serve to play out all the possibilities and work to impart our experiences and ideas to the future and connect with people from the past. Cats and giraffes have no way of understanding the experiences of their ancestors or recording their thoughts. When we consider this fact, art indeed makes us magicians, and the more we can see, hear, absorb, consume, and share, the bigger, wider and richer life is. I hope millions of people discover our humble, heartfelt, magical collaboration. But if in this busy world and crowded marketplace, there are only a handful, then they are lucky and so are we. I am blessed beyond all measure to have this unexpected friendship with another artist arise, and to have created this beautiful project together. I hope it will bless others, too. Click here to get a copy on Amazon. Purchase an ebook copy below. If you would like a free digital copy, email theekphrasticreview@gmail.com with THINKING INSIDE THE BOX in the subject line. Thinking Inside the Box- the Undrawn Art of Poet's Heart

CA$10.00

Thinking Inside the Box- the Undrawn Art of Poet's Heart is a collaboration of words by Portly Bard inspired by the 12x12" signature square artworks of Lorette C. Luzajic. It is a full colour file featuring the art, the poetry, as well as a dialogue between Portly Bard and Lorette on ekphrasis, writing, and looking at art. What Brueghel Might Have Painted But Did Not In the courtyard, men are unloading wagons, and there’s A horse waiting to have his saddle removed, to be Rubbed down and given oats or autumn hay. One merchant talks to another, perhaps his partner. They wear thick wool cloaks, and their gloves are soft leather. They do not notice the horse or the men in the courtyard. They’re concerned with important things: how to get a load Of lumber to Antwerp, what it means to have such an early Snowfall, the Baltic amber someone is offering for sale. The silversmith at the inn kept talking about it. He’d had Too much to drink, but still…. On their shoulders, You can see white specks of snow starting to melt. The horse paws at the paving stones, untended. George Franklin George Franklin practices law in Miami and teaches poetry workshops in Florida prisons. He has a new collection of poems, Remote Cities, coming out later this year from Sheila-Na-Gig Editions, and he and Ximena Gómez have a new jointly written and translated dual-language collection, Conversaciones / Conversations, also scheduled for later this year from Katakana Editores. His website is https://gsfranklin.com/. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|