|

0 Comments

Dear Lily,

a bit hectic of late happens every year fall disappointed many with floods and tornadoes not enough to dispirit our souls the way parisians felt shock waves across the pond wish we assisted more the way lafayette aided our revolution years after pilgrims landed on that rock scraped their knees in humble prayer of gratitude that enough mayflower refugees weathered that harsh first year to carve out a nation and bequeath to us frenzied freedoms of black friday small business saturday cyber monday – I pondered: call you fax or text I felt I needed to keep in touch to keep practicing before cursive, hand-written notes become lost like the ark of the covenant silenced like our liberty bell -- any idea, Lil if signers of our declaration dipped turkey or eagle quills into ink wells any idea whose days were numbered before their blood crimsoned the parchment any idea which ones died before the advent of selective service social security medicare which ones succumbed before age sixty-eight p.s. Lil warmest regards to Ernestine Patrick G. Metoyer Metoyer's first inclination on viewing the painting was to write an early-communications' poem inspired by the black wind- and snow-blown "telephone lines" conjuring Lily Tomlin's “Ernestine-Ma Bell” character dutifully inserting wires into a console to make connections during a storm. Although his poem eventually took a calligraphic turn, Metoyer wanted to pay homage to Tomlin by addressing the letter to her and Ernestine. When he is not engaged in visual arts, Colorado resident Patrick G. Metoyer enjoys reciting and performing his creative writings. His poetry and prose in the past few years have been featured in Grand Valley Magazine. Ups and Downs

We’d snuck into a single malt, a circus of two. His family left for the weekend, while mine had left function behind years ago. I wasn’t missed. It’d begun innocent enough, looking for Trouble, wondering if it’d end in Sorry! I frowned at Life & the boy didn’t have a Clue. I chose Snakes & Ladders. He said, New rules. Land on a viper, more than a token’s goin’ down. Bottle to mouth, I nearly choked on the promise. I upped him, put on a poker face, drawled like I’d done it all before, Let’s do this, strip style. He turns on the stereo, low, lower; Brian Ferry enslaved us as clothes made a grid of the floor. I held my breath with each roll, devilishly, urged him to dash past all virtues, while still so timid of vices. His hand traveled, took the next step. My young heart stopped, slid with his piece. But I gave him an out. He just smiled, said Shh, I won’t bite. Besides, the game's just gettin’ started. And I’ve got all night. Cyndi MacMillan This poem was written for the 20 Poem Challenge. Cyndi MacMillan poetry has recently appeared in Grain Magazine and the Fieldstone Review. Her verse, short fiction and novel-in-progress resentfully compete for her attention. She lives in New Hamburg, Ontario, home to North America’s largest working water wheel. Coffee and family allow ideas to percolate. Passeggiata

Passeggiata noun (Especially in Italy or Italian-speaking areas) a leisurely walk or stroll, especially one taken in the evening O Venice, you forever intoxicate, enfold your love-struck pilgrims in misty indigo -- then reward implied confessions with masquerades and this stirring caligo. Adored, the abiding blur of cobbled salizzade, every potent lamp, bridges below gargoyles, gondolas & their hosts of canals, yet, how regal, even your dampness. O, glass of bride, Palazzo, wicked courtesans revered for likened minds, carnival, Bellini, pretty George Sand, & Vivaldi’s perpetual seasons; all subjects of your realm. Antiquity glazes the commonplace in a princely azure, cloaks the awed in a velvet haze. Behind walls, your citizens dine, while splendor is framed by ancient sills; windows arch towards dreams, cap the night, as dusk refills each starved heart it finds-- O, Ravishing Venice, how do they shut their blinds. Cyndi MacMillan This poem was written for the 20 Poem Challenge. Cyndi MacMillan poetry has recently appeared in Grain Magazine and the Fieldstone Review. Her verse, short fiction and novel-in-progress resentfully compete for her attention. She lives in New Hamburg, Ontario, home to North America’s largest working water wheel. Coffee and family allow ideas to percolate. Fifty Shades of Grey: the Evocative Silence of Vilhelm Hammershoi

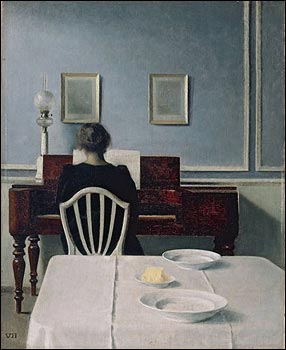

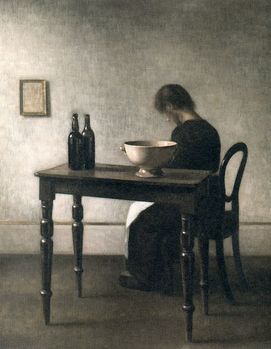

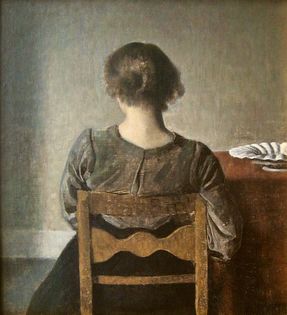

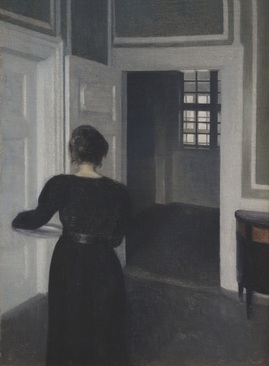

Vilhelm Hammershoi’s curiously withdrawn paintings of muted, spare interiors and a faceless woman in black are most often compared to Jan Vermeer and Edward Hopper. I see the chain of continuity, but Vilhelm’s works also contain an understated current of erotic poetry. There is softness in the hard angles, and a sense of eavesdropping, of happening on a window and looking into someone’s private world. These are not mere depictions of blank walls and pianos and housewives reading letters. They are haunted, too. The grey Dane was a reclusive, elusive man whose art garnered modest recognition in his lifetime. But after his death to cancer, just shy of a century ago, he faded into relative obscurity. There was an important retrospective at the Musee D’Orsay in 1998, and a well-received exhibition at the Met in 2001. Yet Hammershoi remains a cult figure. He is revered by a ragtag assortment of followers intrigued by the unsettling beauty of his images. The works fetch sizeable sums from museums at auction. But, perhaps as he would have wished, he has never found the limelight. By the few accounts we have, we understand Hammershoi was a reticent man, preferring solitude or quiet company. He was described as “taciturn” and shy. He spoke softly, and was painfully sensitive. He had his own kind of closeness with a chosen few, especially his wife Ida, subject of most of his portraits. His paintings reflected the quietude he sought. “Hammershoi’s ‘reality’ is a room devoid of people,” wrote Dr. Kasper Monrad, chief curator at the National Gallery of Denmark. The artist’s legacy was bolstered by a chance encounter with Monty Python’s Michael Palin, who found himself enchanted by the uncluttered, desaturated interiors and the mysterious figure whose back is always turned. Palin said the artist’s grey and sepia paintings stood out from others, “like undertakers at a carnival. These…sparsely furnished rooms, almost stripped of colour, conveying a powerful sense of stillness and silence…there was something about the work that drew me like a magnet. Something beyond appreciation of technique or decorative effect, something deeper and more compulsive, taking me in a direction I'd never been before.” Palin followed his muse to Copenhagen and made a documentary film, thereby dusting off the bygone relic and reviving Vilhelm to a brief vogue. Besides Jan Vermeer and Hopper, there is little to compare to Hammershoi’s work. Alex Colville and Hopper share something of their detachment. They too convey ordinary life scenes with a kind of eeriness that is difficult to pin down. Magritte sometimes used a similar labyrinth of doors and windows to create mystery. And the tonalist artists of Hammershoi’s time certainly influenced his palette with their ranging greys. We know he liked Whistler, for example, because he painted his own version of Arrangement in Grey and Black (Whistler’s Mother). Vermeer’s influence is obvious in Vilhelm’s interior subjects, light, and perspective. Indeed, after the 1998 retrospective, he was dubbed, “the Danish Vermeer.” But Hammershoi distinguished himself from both his teachers and his heirs by stripping colour and detail utterly from his scenes. With all distractions gutted from the narrative, we find in the starkness a stunning, subtle subtext of sensuality. What has been removed, what goes unsaid, what lies beneath, is the real story in these paintings. The shifting light through the window, the people frozen in time. How we are standing at the edge of the painting, looking in, like the artist himself. Hammershoi’s rooms are pared down, and his subjects are oddly unadorned, placing them in a kind of still-life twilight zone. But their quality of isolation does not beg for change. The paintings are evocative vignettes, haikus of sorts to the beauty of the ordinary. One gets the sense that much more would shatter this fragile shelter. He is already overwhelmed. “Each of them looks like the sad home of a recently bereaved widower, whose place has been forcibly tidied up by a cold, hard, bureaucratic, social worker,” writes Christie Davies, who does not see what I see. She chides the artist for having “locked himself into his glum apartment in Copenhagen with his dull…wife and produced dull, glum interiors which he sold to his dentist.” But I think that Vilhelm understands that he has all he needs, even if he seldom leaves his house. Christie minces no words in expressing her repugnance towards the “bleak houses” and bare walls and the “total absence of cheerful, welcoming clutter.” But I find each quiet conundrum to be like the moment of a sharp intake of breath. In their very stillness one can hear the heart beating wildly. Christie finds the Danes’ unusual claim to fame as top producers of hard-core pornography unsurprising in light of such art history. “Perhaps it is necessary to arouse them from their dreadful ennui…Better they add lithium, for their souls are eaten away by spiritual caries…We can see from Hammershoi's work that the Danish sky is an endless undifferentiated grey and there are no hills.” Perhaps. Vilhelm and his wife really did live in the kind of minimalism he portrays, with walls and furniture they painted white themselves. We are painfully intimate to the artist’s awkward reservation. There is the sense of existing apart from the routine clatter and upheaval of life. Indeed, This indicates to me someone who was extremely sensitive and easily overwhelmed. Many said the painter had neurasthenia. This was a popular but vague diagnosis in his time, pointing to a variety of nervous conditions from dyspepsia to chronic fatigue to depression. But I feel there is an attentiveness to beauty, even if it is redefined by minimalism. There is a sense of awe rather than alienation. There is a reverence towards mystery. It’s as if Hammershoi found solace, and soul, in his unique relationship to the world and to Ida. To some degree, he understood or made peace with his own limitations, and he accepted those of his wife. Maybe Vilhelm did not require bright colours and rolling hills for a deeply sensual experience of life. In my study of art, I return time and time again to the writings of Thomas Moore. Moore writes more about music, psychology, God, and even golf than he writes about art, but as an especially gifted observer, he shows me how to see. A recurring theme throughout his work is that real depth of experience comes from entering fully into life’s mysteries, including the painful ones. Instead of viewing every uncertainty, imperfection, quirk, or heartbreak as a pathology that needs to be tidied up and fixed, we can open ourselves to what it reveals about our soul. It’s not that we should never strive for better; rather, Moore acknowledges that both the hands we are dealt and the choices we make lead us into a range of encounters that deepen our very humanity. My sexy has been filled with tumultuous highs and nightmare fall outs, and looks nothing like the serene and vacant world of the Hammershois. Its excesses and lackings have been messy and fraught with dramatics, inconsistent and embarrassing. “Colourful” is a fitting, if polite, description. In contrast, what we can see of Hammershoi’s is reserved, restrained, almost elegant, in fifty shades of grey. So very, very naked. Art allows us to conjure the lives of others. The fact of fiction gives us access to other realities. In speculating on the private world that Hammershoi has revealed publicly through his art, I can’t help but thinking about Moore’s insights on love and sexuality in his books Soul Mates and The Soul of Sex. The paradox of finding such intense sensuality in the chaste, introverted renderings of this painter makes sense through Moore’s lense. That Vilhelm paints interiors with such sensuousness is even more interesting in light of Moore’s observation that, “The word ‘intimacy’ means ‘profoundly interior.’ It comes from the superlative form of the Latin word ‘inter,’ meaning ‘within.’ It could be translated… ‘most within.’ In our intimate relationships, the ‘most within’ dimensions of ourselves and the other are engaged.’ There is a heartbreaking dispassion in Vilhelm’s artworks, rendered in the almost obsessive neutrality of his depictions. Yet the artist remains focused on his wife, allowing all of us to share his preoccupation. His idea of beauty is unadorned, to be certain, but there’s a sense of complete surrender to the terms of the relationship. There’s a tenderness sometimes absent in more raucous, racy, noisy ways of desire. There is an exquisite intimacy within the seeming aloofness. Look at the rapt attention he pays to the naked curve of her slender neck. The few mussed tendrils against the bare skin are almost a fixation. Ida is a geisha. The nape, which the Japanese once saw as a woman’s most erotic aspect, is vulnerable and exposed. Whatever the dynamics of their marriage, there is an understanding between them. There is no tension in the air, and the melancholy is balanced by some kind of reverence. “It isn’t easy to expose your soul to another, to risk such vulnerability, hoping that the other person will be able to tolerate your own irrationality,” Moore continues. “It may also be difficult…to be receptive as another reveals her soul to you. “ Such mutual vulnerability is “one of the great gifts of love.” The gaze of the artist is almost fetishistic, and once you notice it, all the pretenses in the paintings and in your mind begin to unravel. You have a hundred questions. Is the woman waiting in vain to be touched by a man who is too tentative or tepid? Is she playing a losing game of temptation with a husband who is really married to his nervous disorders, or to his paintings? Was this as far as he could go, in his imagination? Or, is this all that she will show him? Is this what she has had to become, for him? The couple had no children. Is the barrenness of these pictures a more literal key? These tantalizing scenarios toy with my inner voyeur, but I keep coming back to the lack of desperation in their distance. There is a comfortable certainty between them. Was the artist so reclusive that he found it safer just to look? Or was Ida the one who was aloof? That she never returns his gaze seems a reasonable clue. Perhaps he cannot bear for her to return his gaze. He is safe where he is. Perhaps she can only bear to be seen, not touched. There is no sex in these paintings, and yet, I feel, that sex is part of their subject. It’s there right away, in our uneasiness when we first find ourselves inside of them. Sex is many things, gorgeous, topsy-turvy, sacred, complicated, ugly, absent. Sex is a shape shifter. Whenever we thing we’ve got the hang of it, figured it all out, come to terms with whatever it is we need to address or accept or change, it reinvents itself and takes us for another sort of ride. We may find our ravenous curiousity about who is doing what to whom shameful and pathetic, but it’s rooted in more than lasciviousness. We are constantly trying to place ourselves and our shoulds and woulds and wouldn’ts on the human spectrum, and it’s a never-ending puzzle because where we find ourselves keeps changing. Every relationship and every unrequited desire changes the dynamic, exposing more of our interior world to ourselves and to others. Sexuality is the theatre in which our most intense fears and weaknesses and our most painful wounds show themselves. Whatever our particular darkness, it rears its ugly head in our sexual dramas. It is where we enact our unresolved rage, losses, regrets, and betrayals. In it, our obsessions and compulsions are manifest. Conversely, it is also where our highest traits are brought to light. It is where we overcome our selfishness and heal deep-seated hurts. It is where we practice generosity, love, fearlessness, courage, openness, commitment, nurture, or self-control. Hammershoi’s paintings are erotic hauntings. More frank treatments of sexuality, or vulgar ones, are in no short supply, and there are pragmatic perspectives and funny, bawdy ones, too. There are spellbinding explicit paeans to desire. But Vilhelm’s paintings remind us that sex is hidden. No matter how many times we have it, or don’t have it, analyze it, moralize it, medicalize it, avoid it, or confront it, there is still more mystery to fathom. In the deepest recesses of our psyches and our bodies is this mystery, the literal meaning of life, which we can never wholly grasp or catch up to. It is obscured even if we are addressing it directly, or doing it, for that matter. We return to it, over and over. We have all of us evolved various defenses and compulsions in response to the heaven and hell or Eros. Vilhelm’s paintings of empty rooms and his evocative portrayals of his most intimate relationship reveal some of his. They are open-ended questions, with a silence that is all at once patient, reverent, despondent, and poetic. He is on the outside looking in, while she is on the inside, looking away. Lorette C. Luzajic Lorette C. Luzajic is the editor of Ekphrastic, an artist, and the author of over fifteen books, including the poetry volumes, Solace, and The Astronaut's Wife. This piece originally appeared in her current book, Truck, and Other Thoughts on Art. Dry Chips

staid corners stilled lives depth, lost in gray- blood's beat lulled, jaded smudged edges surface chilled soundless sitters, shelved displays laboured ponderings disembark a study interned in thought unmoved aged, lost lust, smoked, dry, tasting of endings Deborah Guzzi This poem was written for the 20 Poem Challenge. Deborah Guzzi's poetry appears in Magazines: Existere - Journal of Arts and Literature in Canada, Tincture in Australia, Cha: Asian Literary Review, Hong Kong, China, Eunoia in Singapore, Latchkey Tales in New Zealand, Vine Leaves Literary Journal in Greece, mgv2>publishing in France, RedLeaf Poetry, India and Travel by the Book, Ribbons: Tanka Society of America Journal, Sounding Review, Kyso Flash, The Aurorean, Crack the Spine Literary Magazine, Liquid Imagination, Poetry Quarterly, Page & Spine, Ekphrastic: Writing & Art on Writing and others in the USA. Her new book The Hurricane is available now through Prolific Press. Sidhe

As a kid, you wanted to be a juggler. Even now you hope that one of the balls that Dana, a white bull and wonderful mother, tosses up is a star that bolts from her chest-- she doesn’t drop a single one. You could stay here all night, but you’ve imposed long enough. You leave a gift, songs made from blue delphiniums. Kenneth Pobo Kenneth Pobo has a new book out from Blue Light Press called Bend of Quiet. His work has appeared in: Hawaii Review, Mudfish, Nimrod, Weber: The Contemporary West, and elsewhere. Twitter: @KenPobo. Waterloo Bridge

In London fog, the river stills. In silver sleep, it cools and fills with cobalt mist as dawn unfolds; above the Thames, the sun bleeds gold. Into the haze, it pours and pools like melting opal, liquid jewels until the brume of morning fades to prune the sky with unseen blades that slice the flaming clouds in two to frame a glimpse of Waterloo. Heather Ober This poem first appeared in Poetry Soup, an online forum. Heather Ober is an aspiring poet living in Canada's national capital region. Recess

Free time in the magician’s workshop and all the elementals dance with joy escaping the alembics lamps and holding spells to rise like festive helium balloons to spin and bow and pirouette- as snakes and ladders tilt and slide as jacks jump out of boxes and acrobats leap arms reaching for the next catch across this animated space full of riotous cacophony threatening to blow itself out of the window up to the moon Mary C. McCarthy Mary McCarthy has always been a writer, but spent most of her working life as a Registered Nurse. She has had many publications in journals, including Earth's Daughters, Caketrain, and The Evening Street Review, among others. She has only recently discovered the vibrant poetry communities on the internet, where there is so much to explore and enjoy. This poem was written as part of the ekphrastic 20 Poem Challenge. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|