|

Bonnard in the Alps Dozens of parachutists drift above Mont Blanc, riding updrafts. We're told there is a competition going on: the parachute must come to earth within a given circle, from however many miles away. # We've come around Mont Blanc this morning, crossed from Switzerland into France, on a red train with just two cars. We come as pilgrims, looking for the village church with the Saint Francis painted by Pierre Bonnard. It's the kind of pilgrimage that makes my heart glad: coming through the mountains in the morning, fed on bread and apricot jam, in quest of an almost unknown masterpiece—altarpiece—by the artist whose luminous colour-drenched paintings I have loved most of my life. The Mont Blanc Express is an appropriately pilgrimatic conveyance: quietly jaunty, but well-behaved as all Swiss trains are; short because of the steep uphill pull. For much of the way it acts like a funicular, hauled along on a cable. Everybody else gets off at Chamonix, the car suddenly emptied, spacious, splashed with sun, but we continue on—coming out into the open again with a kind of newborn wonder after having been folded up in the mountains. Now we can see the ranges whole, jagged and white against the sky, immense as portended by their preparatory rise and fall under the climbing train. And then the Icarian parachutists come into focus, higher still. # I ring a bell in the station at Saint-Gervais-les-Bains/Le Fayet to call a man to store our bags while we have lunch and find a hotel. I'm absurdly happy, about to see the seven-foot arched altarpiece Pierre Bonnard painted in 1942 during the war for the church of Notre-Dame-de-Toute-Grâce in the village of Assy looking out toward Mont Blanc—"Saint François de Sales," the sixteenth-century Savoyard saint with the face of Bonnard’s artist friend Vuillard, his friend killed on the road north of Paris a year or two before while fleeing the advancing German army. It's up high, I know, the church with Bonnard's saint, but its exact location is ambiguous. We walk uphill to where the little eglise symbol is on the map, not far from the gare, but as we tentatively push open the nondescript church door and stand in its deserted entry we realize this is a different church. Notre-Dame-des-Alpes. I have confused the Michelin dots. One looks much like another, none of them painted a Bonnard yellow or revelatory violet. There are no other clues to help us find the other Notre Dame on our own. No one around to ask. The streets are deserted too, at this hour. So we walk back downhill past the ornate gates and gardens of a grand old spa like something out of Thomas Mann or Erich Maria Remarque, back down to the station where we started. We ask the only taxi there to take us to the church on the plateau d'Assy. After a moment, when we’ve started to believe it can’t be done, the driver agrees and we set out—across the wide valley, all the way back past the previous train station, and up the mountain opposite. We've been warned that the ride will cost more than our hotel room. # The church astonishes, so high above the world and eye to eye with the Mont Blanc range. It is spectacularly rich in art. The work of fifteen well-known Modernist artists was commissioned for it by the Dominican Father Pierre Marie-Alan Couturier, who’d studied painting with Maurice Denis in Paris, and believed that all great modern art is sacred, the sacrament of our age. We find a vigorously colourful mosaic on its front by Léger; a tiled wall, friezes, and windows by Chagall; a Matisse saint on tile, all willowy black lines . . . and the Bonnard we've come to see, like pilgrims, though not after all on foot—climbing the mountain in our taxi, winding up and up the mountainside of fruit trees and geraniums and old stone. And always the parachutes, pale and distant as moons. # It's dark in Bonnard's corner, and you cry out against that at first. But you just have to let your eyes adjust to it, slowly, the way you quiet yourself and let a place disclose itself to you before trying to take photographs there, or persuade a wild animal to come nearer you. After a time, the colours are some of his richest—pinks and oranges and deep blues and purples and even a couple of highlights of red. There are villages in it (Annecy, it's said, where we will be tomorrow), and at the top, a bird, a purple dove, besides the interestingly colourless supplicants gathered around the vibrantly cloaked saint, blending into the stone and shadows. It's a painting that you have to let come to you, out of the darkness, after you have come to it, humbly as a pilgrim with a heart open to what it has to give you. It's then a communion with well-being, with being as in a deep well—with the intense round of sky above you and the quenching wetness brimming in gray stone. You look at it and feel you have achieved your purpose. Not just in coming here, but in your life. You feel, as Father Couturier intended, “the multiple and living beauty of being.” The presence of the divine. # Our taxi waits for us three-quarters of an hour while we see the church; the driver has gone to see a friend in the village. He tells us it has been mostly sanatoriums there, high on the mountain. The church was built for sanatorium patients. Saint-Gervais itself is a well-known spa town, one of the many where Pierre Bonnard's long-ailing wife Marthe stayed for a cure, and the artist with her. The thermal waters are therapeutic, but in his case nothing short of magical. I think of the blue and gold showers of light he conjured over and over, the famous paintings of Marthe bathing in colour, in radiance purer than life. Danae receiving the god (while her Dachshund dozes untouched on the simple bathmat beside her). # When we get down again, into the valley, feeling we have been much higher and much farther than the winding mile or two of road up, charged with exhilaration, the driver takes us to the place where we can see one of the parachutes just then coming to land: the slow crumpling of red material unerringly into the chalked circle. Christie B. Cochrell Christie B. Cochrell is an ardent lover of the play of light, the journeyings of time, things ephemeral and ancient. Her work has been published by Tin House and The Catamaran Literary Reader, among others. She has won the Dorothy Cappon Prize for the Essay and the Literal Latté Short Short Contest. Once a New Mexico Young Poet of the Year in Santa Fe, she now lives and writes by the ocean in Santa Cruz, California.

3 Comments

Charlotte Berney

5/10/2019 02:05:37 pm

I love this! I feel I went on a small journey of exploration. Lovely writing. Thanks, Christie!

Reply

Carole Mertz

11/13/2019 10:42:55 am

I don't know if you'll ever read this, Christie, but I have to tell you how much I enjoyed reading of your rewarding pilgrimage to see Bonnard's Saint François de Sales. And the parachutists add such a wonderful touch!

Reply

Joseph Egan

7/20/2021 03:05:10 am

Hi Christie,

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

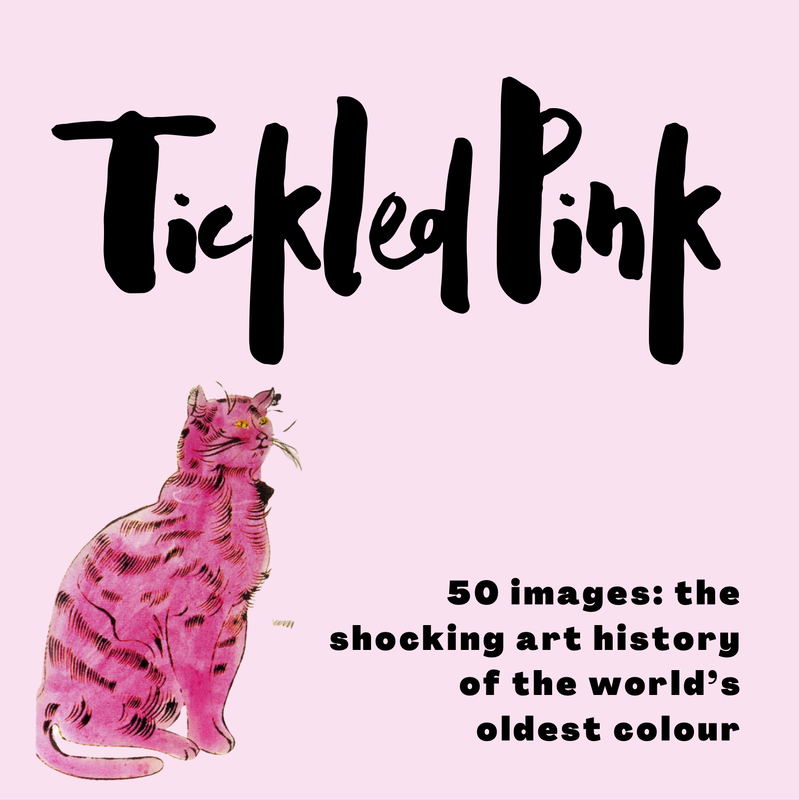

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|