|

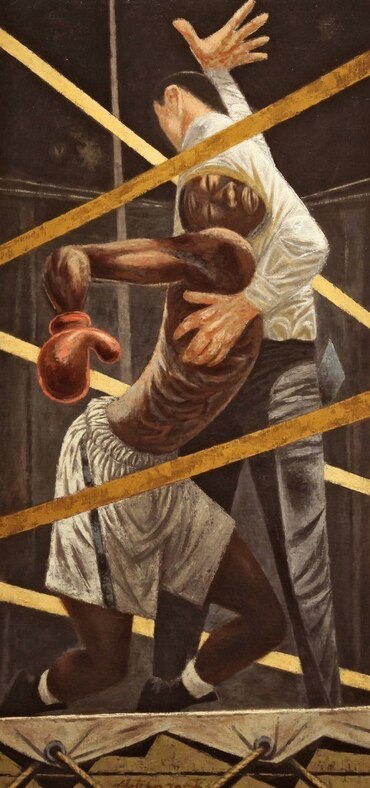

The Undefeated: Homage to Jersey Joe Walcott I In the painting The Undefeated by Fletcher Martin (1948) the all but unconscious Jersey Joe Walcott —born, Arnold Raymond Cream—flows down the chest of the white referee like a waterfall of black water. With his right hand raised the ref signals he’s called the fight. With the left arm around the boxer’s waist he attempts to hold back the flow of water —Joe Louis, the victor “unusually”, as the notation at the side of the painting mentions, is not depicted. Walcott, continues boxing, nevertheless, defeating Ezzard Charles to become the oldest heavyweight champion up till then. It is his second attempt. He is thirty-seven. It is 1951. In the earliest fight I can remember, I am a child sitting at the side of my father. I am in pajamas; my father’s in boxer shorts and t-shirt (he is a shoemaker). It is 1952. Rocky Marciano has just won the heavyweight championship of the world, defeating Jersey Joe Walcott. I have little memory of the bout: the fanfare, the expectation as the ringside announcer introduces the boxers, has them shake hands, turn to their corners as they wait for the bell… even of Marciano—a persistent though clumsy boxer… a slugger…but Jersey Joe Walcott, remains with me: the great mass of the man crumbled on the canvas, the accumulation of years of boxing weighing him down as the force of gravity sucks him toward its infinite center. I remember the flash of the right cross to the chin. Boxing experts calculate it was one of the hardest punches ever thrown. II The rage of Florida’s summer sun at midday fills the halls of the museum with refugees. I stand facing the Fletcher Martin. I arrive from a connecting room where Shiva dances the world into destruction. He holds one arm upward, palm turned to us—a gesture of peace: “Do not fear” Parvati will simultaneously make new what her consort has destroyed: out of one is born the other: Where does one divinity end and the other begin? Buddha—a new acquisition from the nearly destroyed Cambodia—sits lotus fashion, palm turned toward us. I seem to remember an illustration from my childhood catechism book: Christ is walking with children. The colors are bright, children’s colours. It is a Christ depicted for children. He holds a palm up extended toward the child reader. A young mother whisks her two children from the Eastern Divinity hall into this one in which I am standing. I cannot hear what she tells them, but the children seem to listen …for the moment. They pass from painting to painting Two young women, maybe on a high school assignment, sit before an abstract…the artist, a contemporary of Martin’s. They take notes. One rests her head on the other’s shoulder. The rage of the Florida sun has brought us here. III Jersey Joe, you drop out of school at fifteen to take on the burden your father leaves at his passing: mother, siblings—eleven: Your father was born in St. Thomas; mother, from, Pennsauken, New Jersey, corruption of a Lenape word, reminder of history’s entwinement of souls. But where does it begin? How does it matter? Somewhere on both sides —mother’s, father’s—treads the Middle Passage, silent, perhaps, but there, a thread in the weave of the soul. Passage between all that will be—must be-- forgotten and all that must follow. Many survive. Many do not. The sea knows their numbers. No one else. Auction block, fields of cane, tobacco, scars the wads of cotton cut into the palm of the hand. Something must be born of it all, must weave itself into the soul’s—not the body’s—DNA: amorphous yet hard, almost diamond-like yet dark, a darkness that supersedes the darkness of a ships dank hull, confines it to shadows, transcends the odor of flesh rotting on the bone. Not of the body but of the soul, the pull and tug of life—wordless, passed on to the children of the children through the darkness that lights the eyes, a gesture of the hand. IV Arnold Raymond Cream, you take the name “Joe Walcott” to honour a former champion. To which you add “Jersey.” Is it only to distinguish yourself from an old idol and the name “Jersey” is handy…your home? Or is there more? Is it that even the Middle Passage must have end, a place you stake out as yours and it is much later that you become the land’s, not by enslaving the soil but through that feeling on a Sunday Morning, after the brawls and ravages of a Saturday Night? A lone tree survives at the end of a garbage strewn street. A blanket is laid on the grass of a minute park the chaos leaves untouched. And what survives in the soul (molecule or molecules added to the soul’s DNA) of those who have made the Middle Passage comes alive. Your eyes open to the things of this world as if—or through—a seedling of love, and what you love becomes a part of your name, and you a part of a place. Is there another way? In that bout, in that memory of you that never leaves me, as the memory of my father beside me never leaves me, Rocky Marciano may be waiting in a neutral corner for, after all, he was always a clean boxer. And yet I do not see him. The mass of yourself lies crumbled on the canvas. Will you ever get up? How can you not? Vincent Spina Vincent Spina is from Brooklyn, NY. He is a retired Associate Professor of Spanish Language and South American Literature. Spina has published three books of poetry: OUTER BOROUGH: Pecan Grove Press, 2008; DIALOGUE: The Poet’s Press, 2015; THE SUMPTUOUS HILLS OF GULFPORT: Lamar University Literary Press, 2017. Recent poems have appeared In VOX POPULI, an online journal, VEXT, also online and THE BRIDGE LITERARY ARTS JOURNAL.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|