|

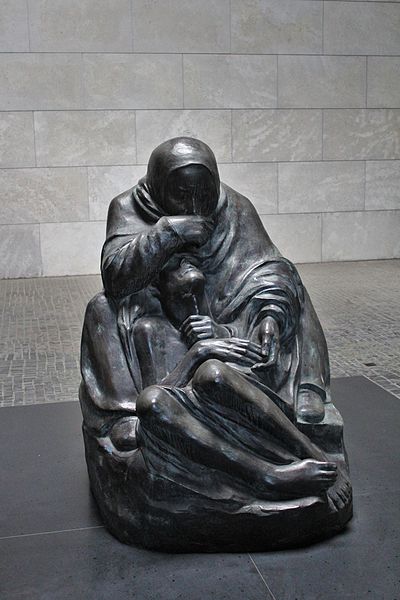

Throbbing with Life "For me, time stood still during the war. It would not fit in to anything earthly. She hovered. I wanted to reproduce something of this feeling in this figure of fate floating in emptiness.” Ernst Barlach Three years earlier, I had been one of a set of American graduate students invited to teach English to future high school teachers in the former East Germany. While there, I naively let my student post an article on the bulletin board about “Good Girls in the Soviet Union.” Sarcastic criticism of such girls for believing what the government said did not go down well with the authorities. Despite my pedagogical faux pas, I was invited back in 1988 to teach master’s students at the University of Rostock, then named for the Communist hero Wilhelm Pieck. My handler was in charge of entertaining me and to make sure I didn’t bring down the regime—or the English Department at any rate. So that first night, he asked me if I’d like to meet his friend Bernhard the next day. The nearby coastal resort had a sauna and wave machine. Sure. I’m up for anything. Why not? That Sunday, we take the S-Bahn and stroll through picturesque Warnemünde to the Hotel Neptune. In the lobby, my handler makes introductions. “Bernhard, Susan. Susan, Bernhard.” We shake hands politely, as all good Germans do. Three minutes later we are all stark naked. Families and friends walk unselfconsciously around with children playing and enjoying themselves. No shame in this northern European haven of extreme temperatures and casual nudity. As the warm mist billows around us, Bernhard and I become quite friendly, given our penchant for standing up to one another’s opinions and enjoying disputation. He wants to leave East Germany to be a business man in South Africa. “South Africa is a wonderful place where a man can make his own way in the world.” “If he’s white,” I point out. This romanticization of political oppression, of a different sort than in his native German Democratic Republic, infuriates me. His not being bothered at all by apartheid would have gotten me hot under the collar, if I’d had one on in that sweltering sauna. I want to convert him to my political views. Sheltered as he is, where the only people of colour he sees are Angolans or Cubans on the S-Bahn on their way to factory jobs, it is hard going. That eventually Bernhard would come to the United States to study engineering, only to court and then marry a woman from South America, is impossible to predict as we sit on fragrant spruce benches, stripped bare to the skin. It is also impossible to imagine that I would one day read a copy of my own secret police file, which neglects to mention my exposed dishabille in a steamy sauna. One day, Bernhard and I take a train to Güstrow. There, we visit the home and atelier of the Expressionist artist, Ernst Barlach. The orangey-red local brick of the chapel-like building is typical of Mecklenburg in northeastern Germany. For this fan of South Africa, Bernhard spouts forth harshly about Nazi persecution. “They called Barlach degenerate. Because he was anti-war.” Ugly-beautiful figures shimmer in his atelier. The beggar with crutches. The laughing old man. The cruciform pietà, with the mother embracing her helmeted son. I have never seen art like this before. Gothic but Expressionist. Ancient anguish at the terror of war with twentieth-century gas masks. Harsh but exquisite. At the nearby cathedral, likewise of brick, the stark Lutheran heritage perfectly frames one of Barlach’s most famous achievements, called The Hovering Angel or The Floating One. I gaze at her face: eyes closed, mouth turned down. Is she sad? Beatific with her arms crossed against her breasts, she transcends sex. The pleated gown gathered about her feet lends modesty and dignity. She soars above us, serenely. Bernhard, a true son of the area, proudly explains. “One of the castings was hidden during the war. Another was destroyed in a bomb attack in Berlin.” The plaque states that the face resembles that of Barlach’s friend, his fellow artist and pacifist, Käthe Kollwitz. Her own anti-war art brought her to the attention of the National Socialists. Threatened by the Gestapo, she was protected only by her fame. Barlach is said to have only realized it resembled Kollwitz once he was finished fashioning it: “Had I wanted something like that, I would probably have failed.” As we leave, I see the floating figure out of the corner of my eye, protecting me. That night, Bernhard and I feast on venison and buttermilk potatoes at a local Schloss, washing them down with a foamy Rostocker Pils. Years after the Berlin Wall is breached, Kollwitz’s peace memorial replaces the eternal light at the Neue Wache. It sits on Unter den Linden in the reunited Germany’s newly designated capital. Buried there are an unknown soldier and a concentration camp victim. While before there had been goosestepping for citizens and tourists, now the mourning mother sits, cradling her son home dead from the trenches. Rain swoops south from the Baltic, dripping through the oculus above her in chilly Brandenburg. Could it be a tear glistens on her cheek? Does she lift her head to gaze into my eyes, holding them still, entranced with her profound grief? Everything throbs with life in Berlin, even the departed. Susan Signe Morrison Susan Signe Morrison, a professor of medieval literature at Texas State University, has published scholarly books, a novel, and poetry. Having taught in the former East Germany in the 1980s, she is currently working on a book about her Stasi (secret police) file which has some unusual—and false—assertions.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|