|

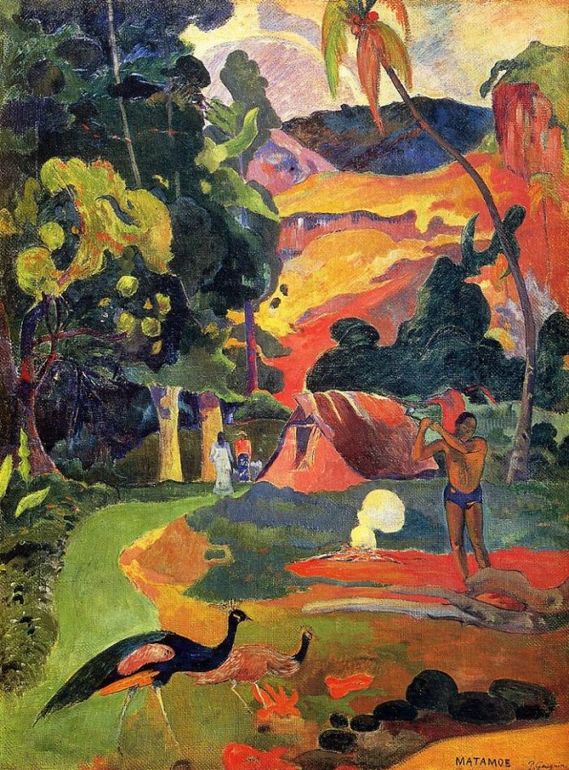

You Cannot Imagine What is Before You It is a curious fact that when something lodges in your mind and will not go away you come across it everywhere. Take the colour red for example. One day I picked up a second hand paperback copy of Joseph Conrad’s first novel, Almayer’s Folly, somewhere, I forget where now. It was an Everyman edition that used Paul Gauguin’s painting Landscape with Peacocks as a cover illustration. Since becoming aware of his work many years ago his bold use of primary colours has been an abiding pleasure to look at, both his Pont-Aven school Breton pieces through to the later Tahiti ones. Reading the first few chapters of the novel I could see why this illustration had been chosen even although the novel is set in Borneo rather than Tahiti, and peacocks are never mentioned that I could see, unless they become symbolic of the ‘folly’ in the book’s title. The editor of this edition tells us that Conrad revised the novel for the collected edition of his novels and excised many phrases and images. Perhaps he was interested in the more sombre vicissitudes that aim for posterity. For example, Conrad took out a philosophical phrase spoken by Almayer: “You cannot imagine what is before you.” It carries a neat ambiguity. Does it mean what is physically before you, or what your future is to be? Luckily this edition of the book follows the text of the first edition and retains such gems. Where has red got to, you ask? Also excised in the early chapters of later editions are references to Almayer’s estranged Malay wife spitting out betel nut juice onto the earth floor of their dilapidated house and making red splash marks. The Sumatran servant has the same habit. Betel nut juice also stains the mouth, tongue and lips; the nut is chewed as a mild intoxicant. Around the feet of the peacocks in the Gauguin picture are splashes of red, perhaps they are exotic flowers, again they could be juice spat from someone’s mouth. This is impossible to judge. A yellow path winds up towards two female figures in the mid-distance that stand side by side beside a small native house. One figure is dressed in white, the other in red. The former could represent Almayer’s beloved daughter Nina and the latter the deranged wife and mother of the girl. The house has a reddish orange glow and a fire burns in the foreground with the same colour and a puff of white smoke. It is difficult also to judge what time of day is being depicted as off to the left is dark green jungle. In the top right hand corner is a weaving block of red and orange that could be sky at dawn or dusk. Much of the action in the novel takes place in the short dawns and dusks of the tropics. The final red in this short novel is: “a long strip of faded red silk with some Chinese letters on it.” This, in the closing pages of the novel has been hung up in Almayer’s house by Jim-Eng, an old Chinese friend and opium smoker, who moves in after Nina departs with her lover and mad mother. Almayer dies; we don’t learn the true cause just that he has been “delivered from the trammels of his earthly folly.” The last owner of this particular copy of the book had left two airline boarding passes tucked between the last page and back cover. They belonged to a Mrs Patricia Salvi, whose name is on them. Both flights were taken about six weeks between each. The first was a domestic flight in Portugal from Lisbon to Porto with Portugalia Airlines on 1st March. The second was an international flight with Philippine Airlines to who knows where and marked by a red immigration departure stamp; this journey taken on 24th April. I could see from the stamp that the flight was in the year 2000. I noticed, almost in passing, that the logos of both airlines contain the colour red. I assumed that this novel of Conrad’s was in-flight reading for the lady; an interesting choice, as the Philippines is geographically close to Borneo. And why take the same book on two separate flights? Conrad is never the lightest of reads, even in this his first novel that was directed at an audience attracted to ‘romance’ and life in far-off places. Perhaps she is a lecturer with a specialist interest in Conrad’s work. If so I would have expected underlining and margin comments in pencil. I guess there are many reasons why somebody should pick up a book and read it. Personally I had always found Conrad’s prose a little difficult, having to concentrate carefully with writing by a Polish born writer who found success writing in his third language. So, I finished the sad tale of Almayer, congratulating myself I had done so and making a mental note to try some of Conrad’s later work sometime. The book went on a bookshelf as I dislike letting books go even if they are never read again. That should have been the end of my association with Almayer’s Folly as it gathered dust on a shelf complete with Patricia Salvi’s two boarding passes between its covers. One day, a while later, I forget how long since reading the book, my doorbell rang. I went and opened the door. A woman stood just away from the doorstep. She seemed to lean back a little with her right knee and foreleg bent forward. She was clearly striking a pose. I guessed she was in her forties, dressed in a dark blue jacket and skirt business outfit with a white blouse, black shoulder bag and shoes. The most striking features in her ensemble were a red silk scarf tied loosely round her neck and bright red lipstick. Long dark hair, brown eyes and olive complexion completed her appearance. As I opened the door she broke into a broad smile like a stage curtain opening on a beautiful scene, for she was indeed beautiful. “Hello, James, I’m Patricia Salvi, I’ve come to pick up my book,” she said in a friendly and melodious voice. There were three questions I could have asked and asked only one: “What book is that?” “Oh, come on now, James,” she began in a teasing tone. “You know, Almayer’s Folly. I need it back now. I could come in and wait a little while you look.” Her voice was mid-Atlantic with a tang of what I took to be Spanish, maybe Portuguese. Somebody well-travelled, at ease in many countries. I was confused by what she said and the half-demand to come in. My wits kicked in a few seconds later, some synaptic processes having made a decision. “No, it’s OK. I know where the book is. I’ll get it for you.” With that I shut the door on her still smiling face. Why I shut the door I don’t know, it was a reflex, some sixth sense that all was not what it should be. I went to the bookshelf, pulled out the book like an automaton and returned to the door, pausing before opening again. When I did open the door again I found her in exactly the same position. The book was given to her without ceremony or any chatty exchanges. Our fingers touched briefly; hers were cold. “Thank you, James. See you again sometime soon.” With this, the smile too, she turned and glided off more than walked. Afterwards I felt shaken by this strange visit and had a stiff drink, a nice malt whisky that slipped down easily. I had another one. Then I asked myself the other questions. How did she know my name? How did she know where to find me? Another question was: How could she even know I had the book? I decided to stay home for a few days and on the third a red envelope dropped through the letterbox. Inside was one of those greetings cards that are blank so you can write your own message. The picture on the front was the Gauguin, and I saw for the first time that the Almayer’s Folly publishers had only used a detail for the cover. To the right of the painting is a man chopping wood. I really couldn’t work out the significance of this figure. The card was signed ‘P’, nothing else. Inside the card were two airline tickets, dated for the middle of May around about my birthday. The first was a Delta flight from Los Angeles to Jakarta, capital of Indonesia. I noted the red part of the airline logo. The second ticket was a domestic flight with Lion Air, with an all red logo, from Jakarta to the city of Balkpapun in East Kalimatan, part of Indonesia on the island of Borneo, where Conrad's book was set. I have written all this to try and explain everything to myself. It is now barely two weeks to flight time. Another red envelope dropped through the letterbox this morning. I assume it will say how I get to Los Angeles. I reach for the malt and pour a good measure. James Bell James Bell is originally from Scotland and now lives in France where he contributes photography and non-fiction to an English language journal. Also a poet he has published two collections to date and continues to publish work online and terrestrially. He was highly commended in the 2016 Tears In The Fence Flash Fiction competition. Recent poetry can be found in the 2017 ebook anthology Flowers In The Machine from Poetry Kit, available as a free download.

1 Comment

Amy

7/30/2017 12:49:14 pm

Interesting read with a twisty addition in the middle. I can imagine the writer's internal debate while sipping his malt. Nice thoughts on use of the Gaugin on the cover of the Conrad book and discussion of his work. Enjoyed the thoughts and inclusion of the colour red in the piece.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|