|

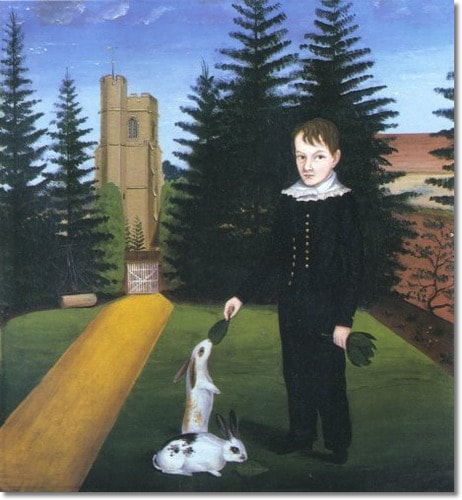

Editor's Note: We had a ridiculous volume of responses to this curious painting. We even had a John Bradley response by someone named...John Bradley! I fell for this strange artwork the moment I first saw it. It was, for me, cute and odd on the surface, in that manner that some folk artworks of the era are, but here the boy's gaze was downright unnerving. I felt so many stories simmer beneath the varnish. Clearly I'm not the only one that sensed a darker vibration bubbling underneath the touching moment, as many of you saw mayhem and murder, too, or at the very least, symbolic reference to the dark heart of humanity. I thank each and every one of you for writing and submitting, whether your work is selected or not. Thank you for participating in this ekphrastic community and the process of discovery of art together. It is a wonderful world of art and poetry, or of ekphrastic flash, that we are building together! love, Lorette The Putney Road Bunnies for Anna, Maria, Pats & Leo The Putney Road (barely suitable for a two-way traffic) defined the thin border between the Freemen’s Common and Nixon Court. And I would find myself violating the said border at least two to three times a day—since my office was situated at the former vicinity and my residence, at the latter. And across from the Welford Road, the University was situated at a short-short distance of < 500 steps. I couldn’t be more grateful for the location and convenience—since the supermarket, odeon, park, pubs, cemetery, et cetera were all within the reach of < 1,000 steps. At the mouth of Nixon Court, sat one of my favourite pubs, The Dry Dock, in the City of Leicester, UK. The said public house offered everything that I cherished—especially, the beer garden, live music, and fish & chips. I frequented the place with my friends & colleagues—at almost every weekend, it was as if our Mecca. … In the Spring of ’06 C.E., Anna, Maria, Pats, Leo & I found ourselves at the said beer garden for lunch—basically, we had come together to celebrate the Spirit of Easter that Sunday. … Almost midway through the lunch, we found an eager brown hare sitting at the foot of our table. But of course, “aww, so cute!” was a natural response from Anna & Maria. But of course, we fed it a couple of lettuce leaves and a few slices of cucumber. After a few of fulfilling nibbles, we saw it running back to the bush—with a leaf of lettuce clutched in the mouth—across the Putney Road. … “‘Alpha Male,’ most probably! Bringing food to the table & providing for his family!” Pats couldn’t help entertaining us with his peculiar sense of sarcasm. … “But, is hermaphroditism also found in rabbits?” Leo couldn’t help boarding the train of inquisitiveness either. … “Rabbit is not a native animal to this Island, did you know? The Normans had brought the mammal with them to Britain back in the 12th century (Common Era). … There’re only three kinds of rabbits found on the Island i.e. the brown, the mountain, and the Irish. … A healthy pair of rabbits can breed and reproduce a litter (6 kittens, on average) at least 10 times a year. … And no, hermaphroditism is a rarity in the rabbit species,” Anna, who was a Zoology candidate at the School of Biological Sciences, added to our knowledge. … On the said Easter Sunday, I got to feed a rabbit for the very first time in my life, too. Also, I coined the title, The Putney Road Bunnies, for our group—in an effort to live up to my reputation for inventing names. Postscriptum As coincidence would have it, I find myself resurrecting this cherished mémoire—one of my favourite souvenirs—during the Easter festivities, too. And this writing prompt at TER couldn’t be more appropriate (coincidental?). But honestly, to my mind, there’re no ‘coincidences’; instead, in the spiderweb-of-multiverse, which part of the string gets plucked when, and which vibrations resonate with whom is what it is! … ‘Easter’, by the way, doesn’t owe its birth to Christianity, but rather its roots are to be found in the ancient pagan traditions, such as, the ancient Sumerian myth of Damuzi (Tammuz) and his spouse named Inanna (Ishtar). … And then, there’s a matter of the ‘Easter Eggs’ in the very Deoxyribonucleic Acid (DNA) of the homo sapiens, too. … As I’ve always maintained: ‘tis only through deconstructing the myth that we can begin to properly comprehend the origins of things. Saad Ali Saad Ali (b. 1980 C.E. in Okara, Pakistan) has been educated and brought up in the United Kingdom (UK) and Pakistan. He holds a BSc and an MSc in Management from the University of Leicester, UK. He is an (existential) philosopher, poet, and translator. Ali has authored five books of poetry. His latest collection of poetry is called Owl Of Pines: Sunyata (AuthorHouse, 2021). He is a regular contributor to The Ekphrastic Review. By profession, he is a Lecturer, Consultant, and Trainer/Mentor. Some of his influences include: Vyasa, Homer, Ovid, Attar, Rumi, Nietzsche, and Tagore. He is fond of the Persian, Chinese, and Greek cuisines. He likes learning different languages, travelling by train, and exploring cities on foot. To learn more about his work, please visit www.saadalipoetry.com, or his Facebook Author Page at www.facebook.com/owlofpines. ** Boy Feeding Rabbits This Boy who's loved and praised by his mother and father, who's coddled by nannies since he was a baby, the Boy has all he could wish for, save for a pale complexion that made him look like a porcelain doll to be handled with velvet-gloved hands, lest it chips or even, God forbid, breaks into a hundred pieces. And because of this perceived frailty, his mother and father cater to his whims, they built him a Tower filled with thickly carpeted rooms, a room for him to wake up in, breakfast on a platter with goat milk, buttered croissant and garden berries, a room for him to read books, not fairytales as they're too dark and violent for his tender mind, a room for him to play with his toy soldiers, a wooden horse for him to ride on, a room for him to rest, a lounge chair next to the carved mahogany desk with a bottom drawer replete with his favourite sweets and savoury snacks, refreshments at the ring of a bell, a room for him to study with the best tutors money could buy for the Boy, for, despite his delicate body, the Boy’s brilliant mind hungered for knowledge, mathematics, mechanics, chemistry, biology, rhetoric, knowledge like possessions nourished his famished mind. In the morning, the Boy would look out to the horizon from one of the rooms on the top floor, imagining the next thing that would satiate him. For his afternoon pause, he would walk on the sprawling property where his mother and father had curated a menagerie for his entertainment, a panda he would kick away if it came to rub itself against his freshly laundered trousers, a ring-tailed lemur he would chase around, throwing rocks at it to make it shriek, a thoroughbred black horse with a blood line as pure as his he would admire from afar, and a pair of rex rabbits he would feed with a leaf of kale, like today. The Boy would grow tall and strong though he will never get rid of his pale complexion which, in time, will serve him well to masquerade his untamable hunger to rise above others he considers less intelligent, less wealthy, less worthy. He would attend the most prestigious universities, land a coveted internship, partly thanks to his father's name, that turned into a senior role though barely in his twenties. He would found his own company, using his wits, trust funds, and knowledge of mechanics and electronics, he would convince the general populace to fall in love with all he would have built, necessary items that didn't exist before people knew they absolutely, desperately needed them. He would grow his company, eat up smaller businesses, pay minimum wages to his workers to maximize profit, send loads of cash overseas. He would amass a fortune even his mother and father never dreamed of, he would continue creating money from money, fly around the world in billion-dollar jets, and have his face slapped on the cover of famed magazines. He would marry a model, the most beautiful woman he could desire, and discard her when he meets the next more beautiful and younger woman, and the next one etc. He would survive gossips, harassment accusations, tax evasions only to gain more fame, make more money, his fortune a far stronger defense than the stone walls of his childhood Tower. He would go on to shake hands with representatives, officials, delegates in the name of charity and the greater good for the lesser people, he would buy our government, chip at our laws, change our policies, seep into our lives and rule over us with a smirk on his pale face. But for now, the Boy is feeding his pet rabbit. A well-fed animal would make a tastier meal. Christine H. Chen Christine H. Chen is a Hong Kong-born, Madagascar-raised, and Boston-based scientist and writer whose fiction work has been published or forthcoming in Tiny Molecules, Gone Lawn, The Pinch, AAWW’s The Margins, CRAFT Literary, Hobart, among others. Her work won an Honorary prize in the 2020 inaugural year of Boston in 100 Wordsand has been shortlisted in the CRAFT Literary 2021 Flash Fiction contest. She occasionally tweets @ChristineHChen1 ** The Majesty of Cabbage He feeds the two rabbits fresh mint stolen just now from mother’s herb garden. He is bored, wicked bored, and there is nothing else to do, so why not let the rabbits gorge? The painter seems to believe mother will enjoy this dull portrait and brag to guests how her clever son taught the mindless rabbits to obey the painter’s every command through the majesty of cabbage. If only she knew the stillest pose cannot still the wanderings of the brain. How even a tamed rabbit can hear the slow, sleepy breathing of the earth. Can smell the bitter scent of animal glue in the wet paint. John Bradley John Bradley's most recent book is Hotel Montparnasse: Letters to Cesar Vallejo (Dos Madres Press), a verse novel about the afterlife of Vallejo. Currently a poetry editor for Cider House Press, his reviews frequently appear in Rain Taxi. ** Colony He’d run out of people to trust, even himself, a boy moon-pale and skittish, the walls between rooms in their home cut so thin it was like being in a single chamber of circus chaos, calamity and danger, but the rabbits outside, they were trusting sorts, famished for not only food, but any kind of sustenance or attention, and what began as a few spare leaves nibbled down on afternoons turned into a ritual of mutual respect, the boy and these animals, so curious they were with their questions about what it was like to be human and free and so utterly rich without even knowing it, and after some months had passed the boy asked his own questions and the rabbits answered what they could, and when he asked if he could be one of them, the bunnies tittered until they understood he meant it, and the bravest of the colony took the boy’s hand, took him to the opening of the hole out back in the vast meadow, asked, “Can you see yourself down there forever?” and without answering, the boy slid down the hole, his laughter echoing back to them, booming with so much joy that the rabbits began to dance. Len Kuntz Len Kuntz is a writer from Washington State and the author of five books, most recently the personal essay collection, THIS IS ME, BEING BRAVE, out now from Everytime Press. You can find more of his writing at http://lenkuntz.blogspot.com ** Coming Coming Closer to My Unvaccinated Lover Rabbit eats cut lettuce like the way a spruce cuts up the pale silk heaven Hold still the grass where I stand out Another rabbit waits like the way the afternoon castles me White-gate mouth shuts the marigold road I walk into fortune’s mouth buttoned to return as the boy not to lose the lettuce I want to feed again tomorrow and tomorrow I want to come closer to you Rabbit doesn’t eat cut lettuce Behind the tower window I’m on the lookout waiting John Milkereit John Milkereit lives in Houston, Texas working as a mechanical engineer and has completed a M.F.A. in Creative Writing at the Rainier Writing Workshop. His work has appeared in various literary journals including Naugatuck River Review,Panoply, San Pedro River Review, and previously in The Ekphrastic Review. His next full-length collection of poems, A Comfortable Place with Fire, will be published in 2023. ** The Puritan I want to be the glum boy feeding rabbits swaths of pine green lettuce. Or is this from a fairy tale-- Rapunzel’s friend, a kid slumped in his black suit, eyes darkened and glistening from lack of sleep? His collar reminds me of a Pilgrim, maybe Hawthorne’s twin. He’s unaware of the dizzying forests that cut through North America. Malcolm X talking of this violent, wild landscape, but that was later: I love you America, though I’m a spoiled brat, though I’m a Goddamn son of a bitch. Sally Cobau Sally Cobau is a writer and teacher from southwest Montana. She's had work published in The Sun, Ekphrastic Review, Room Magazine, Rattle, and other journals. She is a big fan of The Ekphrastic Review, and has a soft spot for the ekphrastic form. ** So Much to Give, So Long to Grieve Jason poses for his tenth birthday photo the suit is three piece and gray like his dad’s His smile is sweet, permanent teeth still large and far apart. He will grow into them. Off to the right side of the frame, a Norway Pine stands taller than the boy, his birth tree. He loves his kitties, helps feed them kibble, but his heart is with Wolf, his Malamute. On weekends, he shares Wolf’s House, lying inside on the clean straw he refreshes every few days. In back of him, the small white house peeks between the trees, two pear trees and a crab apple. One day too soon, the tree will die, and so the boy goes also, a young man. His faithful dog waits on the hill. Jackie Langetieg Jackie Langetieg has published poems in journals and anthologies and won awards, such as WWA’s Jade Ring contest, Bards Chair, and Wisconsin Academy Poem of the Year. She has also been nominated for a Pushcart Prize. She has written six books of poems, most recently, poetry, Snowfall and a memoir, Filling the Cracks with Gold. www.jackiella.wordpress.com ** Young Heathcliff Young Heathcliff, though young and tender of face but dark and gloomy of mind waits for Catherine while feeding the demons of his heart, by portraying a tender stance, at the helpless and ignorant creatures, knowing not, that the hand, that feeds will soon strangle it for mirth because so has he learnt from life since birth. The brewing hatred and turmoil that he hides in his eyes can burn the Wuthering Heights to ashes bus ‘tis Catherine, his only light, that blinds him binding his soul and enshrouding his mind, leaving him as helpless as the creatures he feeds. He knows that her warmth is a trance as Egdar’s beauty and wealth wraps her heart but her love is like smoke, covering his senses one, he cannot hide or deny, hence, he plans of leaving the estate and returning as an established youth to claim what has always been his own; plotting the future, he looks afar, not knowing that the leaf he feeds to the creature has the essence of a poisoned flower. Aditi Kataria Aditi Kataria, age 25, lives in Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. Her poems are scheduled to feature in The Wise Owl (2022). Her poems have also appeared in Visual Verse (Vol 9, Chapter 5), Ink Babies Llc. (Issue 1, 21), Blydyn Square Review (Fall, 21) and The Criterion (Vol 9, 2018). She considers herself as open, approachable, adaptable, curious and optimistic, with art, literature and culture as few of her sundry arenas of interest. ** Toby Our manor looks sturdy enough. Mayhap it fools the traveler from a distance. Walk the path to the front gate, though, and witness the rusted iron, how it groans and sags when pushed. We tread the steps with care, avoid the listing stone, the cracks that gape, and yet make haste to get inside lest some crumbling gargoyle bloody our heads. Yes, sir, I know. You’ve told it oft. We’ve fallen on hard times. Hunger gnaws at my entrails, fogs my brain, stutters my heart too. But please, sir, let me feed my dear, dear rabbits one time more. Let them gaze on me with affection, and I, them, before they be throttled for our repast. CJ Muchhala CJ Muchhala’s work has appeared in anthologies, print and on-line publications and art / poetry installations. She has been nominated for the Best of the Net award and twice for the Pushcart Prize. She lives in Shorewood, Wisconsin. ** The Peril of Feeding Rabbits The boy was an only child, born into an aristocratic family. Being preoccupied with whatever such families were preoccupied with, his parents appeared disinterested in him. He tried to please them but didn't know how. He spent much of his time with his governess, who was responsible for his education, decorum and manners. She was kind enough but humourless. There was little humour in his life. He was lonely except in the company of rabbits. He was sad but didn't know why. The immaculately manicured garden was the domain of the gardener, Mr. Forsyth, who thought the title horticulturalist more befitting his station and experience. The boy was permitted in the garden but warned not to stray from the path, and to visit only when Mr. Forsyth was at lunch, which occurred at precisely the same time every day. The rabbits did not live in the garden (a wise decision on their part). Hopping through the hedge when the boy appeared, they were eager for treats he procured from the vegetable patch outside the kitchen. Cook selected produce frequently so a few spinach leaves were not missed. He loved the rabbits' loopy ears, the way they sometimes stood upright to take food from his hands. He was amused by how they munched and chewed. He would never be permitted to eat like that. One day while happily feeding the rabbits, the boy heard heavy footsteps and grumbling noises. Returning early from lunch, Mr. Forsyth stopped in his tracks on seeing the boy and stared at him in disbelief. Wondering what fate might befall him, the boy looked anxiously at the gardener. The rabbits continued to munch and chew nonchalantly. Roberta McGill Roberta McGill grew up in Ireland where she loved reciting poetry as a child. She immigrated to Canada with her husband and lives in Orillia, Ontario. Her poetry has won several awards at the annual K. Valerie Connor Memorial Celebration, Orillia and has appeared in several anthologies. She is a member of The Ontario Poetry Society. ** The First of Many From the moment James Williams emerged from his mother’s womb, slick with blood and desperation, everyone knew there was something wrong with him. His mother’s hair laid in clumps on the floor, her scalp raw and exposed from his unforgiving grasp. As he got older, his fists grew in unison with his rage. The violent waltz between James and his parents left holes in the sturdy castle walls that could not be fixed. When they tried to feed him his morning porridge, the walls ended up splattered in lumpy mush. His appetite begged for juicy, expensive meats, like an insatiable wolf. By the time he turned ten, he had seen just shy of seven different physicians who all told his mother the same thing, “You shouldn’t worry about a thing, Mrs. Williams. All young boys go through a period of aggression. Plus, there’s nothing wrong with getting plenty of iron!” But Mrs. Williams’ vivid dreams of carnage and massacre left her restless each night. On a late May afternoon, James went outside to play in the garden. His mother could not ignore the ache in her stomach and the thumping inside her chest. She sat at the kitchen table with the taste of metal bombarding her dry tongue. The chamomile tea beside her grew cold before she finally went outside. Smoky skies replaced the spring sun, robbing the courtyard of its usual lively spirit. As she walked the marathon toward the garden, her feet heavy with unease, tiny drizzles cascaded onto her cheeks from above. She turned the tree just before the garden and was greeted with the sweet symphony of her boy’s laughter. Two white rabbits munched quietly by his feet while he fed them bunches of basil. The sinking in her belly shape shifted into flutters of adoration. Mrs. Williams started her way back to the castle when two ear-splitting cracks resonated from the garden. She sprinted back toward the gate, the sinister snickers of her precious angel engulfing her eardrums. With his back facing her, James stood proudly, his hands dripping with crimson and ivory. Mrs. Williams never found their heads. Sarah Mengel Sarah Mengel is an emerging writer from Pennsylvania. She is currently in her junior year of college, majoring in English and minoring in Professional Writing. Her pieces vary in genre, but she enjoys writing poetry, flash fiction, and short stories about many different topics. ** Window View The tower window behind which I stand is rusted shut. Yet there is a pane of glass missing, providing me a narrow view of the scene below. From my vantage point, I can only see my son's back, for he is looking at Mr. Bradley and, I assume, frowning, as is his way. He had wanted no part of this endeavor from the outset when I first broached the idea for the painting and had sighed exasperatedly, oh mother, what a waste of time and money. Which made me laugh, for it sounded so like his father, gone astray these many years. But I insisted, and this morning I laid out his best pearl-buttoned suit with its white cravat, combed his flyaway hair into tidy pomaded waves, and sent him down the spiral staircase to the garden beyond the gate. Lettuce had been plucked by the gardener early that morning, and the rabbits freed from their hutches. I had arranged for a log to be stationed just inside the garden gate, where I had hoped I might sit and watch the proceedings up close, but my son had protested so adamantly I did not force the issue. And so it is I remain up here to look down from afar. One of the rabbits just now raised up on its hind legs to nibble at the food. How dear a scene! But I know my son would not be amused. He is serious by nature and tolerates no frivolity, much like his father in that regard, who had abandoned us to go back to the old world and leave us stranded in this new country with its odd ways. Margaret Ryan Margaret Ryan became interested in ekphrastic writing after taking an Ekphrastic Review workshop online and a university-sponsored art appreciation class. Her poem, Vermeer Reimagined, was recently featured on olliconnects.org, the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute's blog at the University of South Florida. She lives in Florida where she writes and paints. ** They Won't Make Me I know how to do it, but if I say I don’t know, they won’t make me. They will sigh and curse and call me names. But they won’t make me do it. They will shove me, cuff me, pull my hair. But they won’t make me do it. They will say I’m stupid, I’m lazy, I’m no good. They will sigh loudly, shake their heads, raise their arms in despair. But they won’t make me do it. I don’t care. I don’t want to do it. It’s boring. I want them to leave me alone, so that I can play games by myself. I know what they say about me. I know what they want. They want me to be like them, all day, walking, back and forward, their steps an echo through a warren of bustling self-importance. Everybody walking where they ought, with their reasons and their tasks. I don’t like this lacy collar. It itches. The hot prickle of the barbed linen, a dry scratchy hold on my throat. I can hear it every time I move, every time I breath. They want me to feed the rabbits; hot, furry, moving things. They take the rabbits from the hutch; a hobbling, lumpy chase on the lawn, a slow farce. The rabbits huddle together, frightened of the too big space. I watch, but I don’t help them. I’m a boy who is going to be in a painting. Jessica McCarthy Jessica McCarthy is a high school English teacher from Adelaide, South Australia. She has a Master’s Degree in Writing and Literature, specializing in Children’s Literature, and enjoys finding new ways to inspire her students to read widely and write creatively. ** Yon Frederick Yon Frederick has a sly and shifty look. Beware the boy who dons lace collar with no complaint. Would he were a stable boy, fresh from mucking stalls. While Sister reads The Aeneid, under watchful governess eye, yon Frederick slips rhubarb leaves to bunnies most beloved. He will watch with hooded eyes Sister’s rabbits die in agony (a hollow victory, to be sure). Elizabeth Gauffreau Elizabeth Gauffreau has published fiction and poetry in numerous literary magazines, including DASH, Natural Bridge, and Woven Tale Press, in addition to a novel, Telling Sonny, and a poetry collection, Grief Songs: Poems of Love & Remembrance. She lives in Nottingham, New Hampshire. Learn more about her work at http://lizgauffreau.com. ** The Rabbit Whisperer of Oz Stranded beside the yellow brick road, and coming to the end of the soft green leaves torn from the tower walls, the ones the rabbits like best, the ones that allow them to speak for three minutes, the boy listens to their soft urgent voices telling him of the race through the fields of poppies, to the land of chipped china figures, the well filled with ink, their voices fading faster and faster all the way to wordless depths. What will he do when the leaves are too new to harvest? Who will skip all the way up to the gate while he waits for the rabbit's soft words to return? What stories will the travelers sing, so long as they can sing without a diet of leaves? Will their songs fade too, while they grow greener and greener dancing into the distance? Sarah Ann Winn Sarah Ann Winn’s Alma Almanac (Barrow Street, 2017), won the Barrow Street Poetry Prize. She’s also the author of five chapbooks, most recently, Ever After the End Matter (Porkbelly, 2019). Her work has appeared in Five Points, Smartish Pace and Journal of Compressed Creative Arts, and elsewhere. ** Acres of Loneliness Some called me lucky, for I had a castle, a palatial place for a boy to roam. I called it a prison, with its drafts and dark hallways, rooms that formed imagined cells. There were no locks. There were no guards. There was no one. In the distance, I heard children’s laughter, young souls joined to find joy. My sliver of joy, was the animals in the field, creatures with kind tongues. They did not mock me. They did not scold dirty collars. They did not forget dinner. Some were sneaky, as children should be, mouths stealing gloves like leaves. I took their lashes, willing to protect them, shelter that should have been mine. From the ones who vowed to care. From the ones who trained a dutiful master. From the ones who now hide in the trees and weep for their castle has holes. Corrie Pappas Corrie Pappas is a small business owner living in New England. She self-published the children’s book, Come Along and Dream, several years ago and has written poetry since childhood. ** Ghost Boy My husband wanted a child, so I divorced him—left him for a ghost. A real ghost, I’m not being metaphoric. The ghost scared me one Halloween—flew out of the bushes on my walk from the bus stop. Haunted me all the way home. I screamed, then fell in love. It’s surprising how similar being scared is to being in love. Both leave you breathless. And full of oxytocin. You know what else is surprising? Ghost fertility. I did not think birth control would be required. My mother called it a miracle. She was so desperate for a grandchild she did not care that he was half-ghost. I did. The pregnancy was sobering. I was not the kind of woman that mingled with the paranormal. I didn’t even like astrology! The ghost was a mistake. A secret to go to the grave. He begged to marry. To be an active father to his son. I said no. I would raise the boy alone. I never wanted to be a mother, but it was too late, the boy was here. I would give him a good life. The ghost had done enough. The boy was strange. My mother said I was being paranoid. She said he was the same as any other child, but I saw it. There was a quality. He loved rabbits. His first word was rabbit. He must have been a magician in a past life. It didn’t come from me. I am not an animal person. He asked for a rabbit for his first birthday. I said no. Then my mother bought him two. This made me very upset. I cannot care for a child, and pets, I said. They are for the boy, my mother said. He will take care of them. And the boy agreed. He was twelve months old, but mature. An old soul. Like his father, I guess. The ghost was seven hundred and ninety-three years old. I saw his birth date at his gravesite on our first date. A picnic. We ate sandwiches with brie. I told the boy his father was dead. This was not a lie. The ghost flickered the lights to object. Turned the television on when I went to bed. The ghost whispered: It is not something you can hide, you know—the truth of who you are. Don’t even think about haunting this house, I said. I am not like the other children at school, the boy told his rabbits, when he was five. He fed them leaves in the backyard. The white rabbit with the brown patch over his eye chewed on a stem. How so? he said. They are so happy, said the boy. It disgusts me. The other rabbit, also white, but with a black patch over her eye, laughed. I know exactly what you mean, she said. The boy looked at me with disdain. He did not like it when I watched him through the window. I couldn’t help it. I was always staring. Waiting. He should be practicing transparency by now, said the ghost. His face flashed like a hologram in my hallway mirror. I jumped, spilling my tea. He hadn’t been around in a while. He’s five, said the ghost. I was a master of invisibility by four! I waved my hand. No, I said. The boy is a human. The ghost turned my tea cold. You cannot keep me from my son, he said. I put the mug in the microwave. Don’t make me call an exorcist, I said. The boy was miserable. I was a failure of a mother. I tried everything to make him happy. I bought him milkshakes. I filled his room with chocolates and cake. He just complained about the ants. When he turned six, he disinvited the children from his birthday party. Canceled the clown. Would not even open his presents. I give up! I said to my mother, I can’t do this anymore. This boy is not a boy, he’s a demon! He heard me. It was not my intention for him to hear. I’m sorry, I said. The boy disappeared. I called out to the ghost for help, but he didn’t answer. Wouldn’t even respond to the Ouija. I kept the rabbits. I named them Allan and Frida. I fed them leaves in the backyard. He never pandered, I said. Never tried to fit in. Allan nodded in agreement. I ate one of the leaves, just to try it. I tried to make him someone else, and I failed us all. Frida looked to my left. The wind made a rustling sound in the grass. Aileen O’Dowd Aileen O’Dowd lives in Toronto. Her fiction has appeared in the Berkeley Fiction Review, Monkeybicycle, and Flash Fiction Magazine. ** Prodigal Musings They prefer my dew-soaked greens. I prefer the spoils of their fecundity. Let them destroy the exotic plants. They can pillage the gardens, too. I like that. I like to keep the game alive. The gardener exhausts himself: traps and cats and vegetable cages while wild ones dart in every which way. We have wool coats buttoned to the neck A castle erect. My room is empty and cold. They warm together in the dark of their caves. Wrassle in the dirt and dried leaves. These rabbits keep coming and coming, bring cousins and predators in an orgy of play. Let them take from me these tender leaves Let them be brutal in beguiling ways. Emily Fernandez Emily Fernandez is an assistant professor at Pasadena City College where she teaches composition, creative writing, and poetry. She received her MA in English and American Literature from New York University. Her poems and/or art have been published in Pangyrus, The Dewdrop, Angel City Review, and several others. Her poetry chapbook, Procession of Martyrs, was published in 2018. She was selected to be a 2020 Moving Arts MADlab playwright, and her play Cage and Lung was professionally performed online in October 2020. She also enjoys open water swimming, gardening, and photography. She lives in El Sereno. https://emily-fernandez.weebly.com Contact: [email protected] ** Absent Prince Wisps of cloud above an embattled tower; behind the window sits, one could wish, Rapunzel, tresses ready to be unfurled; a golden pathway, sans perspective, rises to a shut gate, while all around firs taper skywards. And the prince stands on the lawn absently feeding rabbits, blank faced, as if the artist’s easel in fact supported a barely nascent, yet-to-be light box, its shutter open too long for revelation. Something about this prince, his back turned, undoes adventure, appetite, appeal—no heed does he give to: the critter at his feet, up on its haunches, striving; what’s there to be grasped; a song floating by. Alan Girling Alan Girling writes poetry, mainly. His work has been seen in print, heard on the radio, and viewed in shop windows. Such venues include Panoply, Hobart, The MacGuffin, Smokelong Quarterly, FreeFall, Galleon, Blue Skies, The Ekphrastic Review, CBC Radio and the streets of New Westminster, BC. He is happy to have had poems win or place in local poetry contests and to have had a play produced for the Walking Fish Festival in Vancouver, B.C. ** Winston’s Rabbits Against his father’s advice, young Winston developed a close attachment to his pet rabbits. His father said that he should be out in the fields shooting rabbits rather than petting them. Caring for animals, particularly pets, in the early 19th century was considered “girls work.” According to his strict father, such work was demeaning and unmanly for a boy. But Winston persisted. Risking ostracization, he continued raising and petting rabbits well into his adulthood. Many years later, after graduating from Harvard and becoming the renowned zoologist who developed the first working prosthetic for severed rabbit’s feet, Doctor Winston Lippman told those who gathered at one of his many award acceptance speeches a story that had profoundly altered his life’s trajectory. One evening at the family dinner, he began, he realized that what was being served didn’t look like what had been advertised. “This doesn’t look like chicken,” the boy exclaimed. “It is chicken,” his father retorted, without making eye contact with the boy. “It’s not,” the boy shouted. At that, his father broke into hysterical laughter, and Winston stormed out of the room, knowing that he was leaving behind one of Flopsy’s or Mopsy’s hind legs on his dinner plate. Jim Woessner Jim Woessner works as a visual artist and writer living on the water in Sausalito, California. He has an MFA in Creative Writing from Bennington College. His publishing credits include The Daily Drunk, Flash Fiction Magazine, Close to the Bone, Adelaide Magazine, Potato Soup Journal, The Sea Letter, and others. ** Rhymes and Reasons Oh, where have you been, Billy Boy, Billy Boy, Oh, where have you been, charming Billy? The song ends abruptly. In a sudden reversal, the blue sky turns black, riven with thundering arrows of fire. The tower, struck, cracks and falls burning though the gate, consuming the carefully manicured lawn, the path, the ivy covered walls, the buildings, releasing the demons that have been hidden for generations behind flat painted masks. Everything empties, exposed, cast into ruins. The meticulously curated order turns inside out, becomes a massive upheaval of smoke mirrored as dust. How do you do? And how do you do? And how do you do again? The boy has vanished. Two rabbits hover above the debris, their wings unfolding in the shifting landscape. The vacated space formerly occupied by the tower exhales, released of its burdens. Ancient spirits realign. Ashes! Ashes! We all fall down Kerfe Roig Kerfe Roig lives and works in New York City. ** The Velveteen Boy (after Margery Williams) When all is moon and shadow, when white moths flutter in velvet blackness, when, for a few scarlet drops of blood, raspberry canes offer fistfuls of fruit, the Boy lives his Real life. Forgotten: bland foods, sponge baths, windows pulled against deadly drafts, mustard gargles for his throat. Loneliness beyond quarantine and convalescence. Vigilant adults. When all is moon and shadow, the Boy flees shorn lawns, gated gardens, steals into forbidden, whispery woods. His rabbits slip their belled collars. He sheds his own stiff lace, regiment of buttons and boots. Such gloriously silky, perilous night air! He tiptoes through thickets where birds dream, sips shivery dew from moonflowers, curls deep into burrows when swooping talons wing past. Trembles at a sudden cut-off scream. In the moonlight, in the long grass, his rabbits dance with the wild hares. The Boy dances, too. Leaps. Spins. A creeping warmth flushes his wan skin, streaks his lank hair with faintest gold. The sky pales. Time to return to his pretend-life. But, the Fairy has promised. Soon, he will be Real “for always.” Mary Rohrer-Dann Mary Rohrer-Dann, author of Taking the Long Way Home, (Kelsay Books 2021), and La Scaffetta (Tempest Productions) also has work in Orca, Clackamas Review, Ekphrastic Review, Philadelphia Stories, Panoply, Third Wednesday. A “graduated” educator, she paints, hikes, gardens, and volunteers at Rising Hope Therapeutic Stables, Big Brothers/Big Sisters, and Ridgelines Language Arts. She hates trying to write a sexy bio.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Challenges

|