|

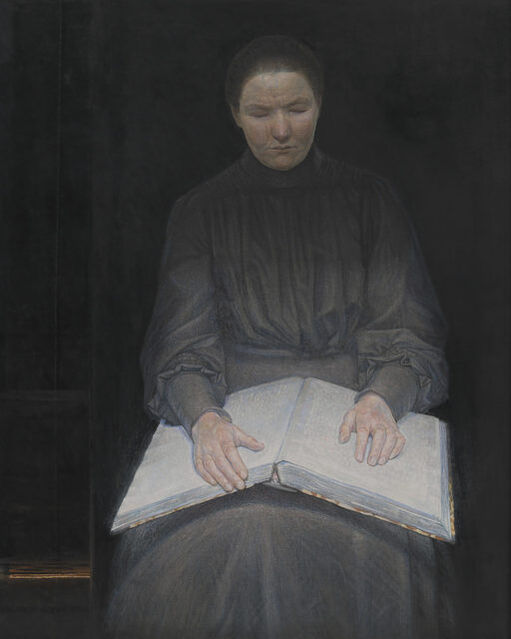

Blind Girl Reading, by Ejnar Nielsen Incidental to the evidence That meaning proves Like a dough, That thoughts do reach out From the page And claim us, knead Us into form, rise - An experience of the word So bodily, eyes In the meeting Of print and finger, Each word A journey your hand Must travel, send postage Until the very shape Becomes an object In itself: Here the delicate curve Of a question The scalding exclamation Here the wood ferns Batting their damp eyelashes Against her legs, The scent of a small happiness And the relentless sound of rain. Jenna K Funkhouser Jenna K Funkhouser is a nonprofit storyteller and author in Portland, Oregon. Her poetry has recently been published by Geez Magazine, As It Ought To Be, and the Saint Katherine Review, and was a runner-up in the National Federation of State Poetry Societies: Poetry Society of Indiana Award. ** Autodidact To find out what your convent school and your parents don’t or won’t tell you, you go to the other bookshop, Hogan’s, (not the one where your aunt works), with the pocket money you’re meant to be saving for the class trip to Lourdes. You saunter along the Classics aisle as if you’re looking for one of those ‘get me a husband’ Jane Austen books your English teacher, Mrs. O’Brien, approves of. You reach the Young Adult section and glance around to check that the sales assistants are preoccupied and that no-one you even remotely recognise, not even the fella who cuts your grass, is on the premises. ‘Delivery!’ a man calls from the doorway, and you exhale as staff surge towards the stack of boxes. Picturing the cover image from the page your best friend, Nessa, had torn out of her older sister’s Just Seventeen magazine, you scan the shelves: A… Alcott no…B…J.M Barrie no… Frank L Baum no…Bl…Bl…Blume, Judy Blume. Yes! There are just two Judy Blumes, so you cross your fingers and hope one is Forever. Oh thank God, you think, as you ease the spine out. Your heart rages in your ribcage: it has never been this agitated since Sebastian, the neighbour’s French exchange student, smiled at you. The book shakes in your hand and you look around once again to make sure no-one is watching. You flick through the pages with your jittering right thumb. Words whizz by: tongue, kiss, fingers, love, fire-side, and Ralph. Who’s Ralph, you wonder. Bayveen O'Connell Bayveen O'Connell has words in Maryland Literary Review, Reckon Review, Fractured Lit, Janus Literary, Bending Genres, The Forge Lit, Splonk, the 2021 Micro Madness National Flash Fiction Day NZ, the 2020 National Flash Fiction Day Anthology, 2019 & 2020 National Flash Fiction Day Flood, and others. She came third in the Janus Literary Spring Story Prize 2021, and received a Best Microfiction nomination in 2019. She lives in Ireland and is inspired by art, travel, myth, history, and folklore. ** Blind Woman Reading Bullets scattershot Austen & Wollstonecraft In tuples of six Across the pages Whispering through your fingertips The feel of blue The voices of women Donna-Lee Smith This is Donna-Lee Smith's first ever poetry submission at the age of 72. ** the seer they think it is dark here because they turned out the lights they think I don’t see because my eyes are closed they think I wear their dowdy dress but I am garbed in stars they think I read their braille bible but I illuminate it with my finger tips and at night, when they sleep I sing the dreams to them that they are blind to in the light of day Dick Westheimer Dick Westheimer has—with his wife Debbie—lives on their plot of land in rural southwest Ohio for over 40 years. He is a Rattle Poetry Prize finalist. In addition to Rattle, His most recent poems have appeared in Pine Mountain Sand and Gravel, Paterson Review, Chautauqua Review, RiseUp Review, and Cutthroat. Much of his work can be found at dickwestheimer.com ** None So Blind as Those Who Will Not See My neighbours hide from me. The moment I step into a store, church hall – even Mama’s parlour, they clam up. No one here. They act like blindness is contagious or an evil curse. I know Mr. Larsen suspects I’m a witch. Just unnatural how she can mosey around town like the rest of us, he says. I overhear conversations, recognize voices. Footfalls, rustling skirts, and body odors complete the picture. From Sue Olsen’s cloying rose water to Larsen’s eau de chicken coop, I can pinpoint them. Nice to see you, Mr. Larsen, I say as he rushes out the door I’m grateful for the little ones – so curious, eager to ask questions, accept new things. Mimi comes up, slips her little hand in mine, Miss Lily, will you read me a story? She loves to watch my fingers dance over Braille. Books are my life. I can ignore the small minded. Alarie Tennille Alarie Tennille was born and raised in Portsmouth, Virginia, and graduated from the University of Virginia in the first class admitting women. Thanks to fellow poets, who generously share the hottest poetry news, Alarie visited The Ekphrastic Review a few months after its birth and decided to move in to stay. She’s been a consultant for prizes, occasional judge, and received one of the first Fantastic Ekphrastic Awards in 2020. Please check out her three poetry collections on the Ekphrastic Bookshelf. ** Blind I wonder how you can be blind to what I am going through Tear tracks form a braille pattern down my cheeks but you refuse to feel it I wonder how you can be blind to what you have become Your mood swings braille along life’s page but you refuse to read it The eyes see it all Something, nothing, everything except themselves Nivedita Karthik Nivedita Karthik is a graduate in Immunology from the University of Oxford. She is an accomplished Bharatanatyam dancer and published poet. She also loves writing stories. Her poetry has appeared in Glomag, The Society of Classical Poets, The Epoch Times, The Poet (Christmas, Childhood, Faith, Friends & Friendship, and Adversity issues), The Ekphrastic Review, Visual Verse, The Bamboo Hut, Eskimopie, The Sequoyah Cherokee River Journal, and Trouvaille Review. Her microfiction has been published by The Potato Soup Literary Journal. She also regularly contributes to the open mics organized by Rattle Poetry. She currently resides in Gurgaon, India, and works as a senior associate editor. Her first book of poetry, She: The reality of womanhood, was recently published by Notion Press (available on Amazon). ** Guide Light pours through my fingers onto the prickled page. Your eyes pour their light onto the skin of my hands, your brush sculpts the contours of my inward face. I read heat through the closed edge of our bedroom door, the oil-lamp trimmed low, waiting to light you to bed. In the pure dark I will be your guide. I will study the vellum of your skin. I will teach you the contours of fire. Monica Corish Monica Corish is an award-winning writer of poetry and fiction, and an Amherst-trained writing group leader. She is currently working on a novel set 6000 years ago in the north-west of Ireland. www.monicacorish.ie ** Retina northern light the colour of ashes leaches from the window in front of her ice has layered gauze strips of great delicacy left a dripping hem of silver globules shimmering across open water formed viscous scars, a mess of threadbare beauty that butts against the bottom frame. Aside from her pale face, her hands and the pages of her book where her seeing left hand unlocks other worlds, letter by letter her world is infused with unadorned shades of grey. Yet down there, like an afterthought – that thin strip of warm light signals belonging from underneath the closed door. Barbara Ponomareff Barbara Ponomareff lives in southern Ontario, Canada. By profession a child psychotherapist, she has been fortunate to be able to pursue her life-long interest in literature, art and psychology since her retirement. The first, of her two published novellas, dealt with a possible life of the painter J.S. Chardin. Her short stories, memoirs and poetry have appeared in Descant, (EX)cite, Precipice and various other literary magazines and anthologies. She has contributed to The Ekphrastic Review on numerous occasions and was delighted to win the recent flash story contest. ** Room Mopes The door allows only a portion of day to enter her room. It peeks inside the way a child seeks his toy under the bed. A book climbs into its owner’s lap as the scent of day breaks upon her. She pays attention to its details, drifts hand to find doors, crossings, places she visits regularly. Behind her the rest of the room shadows in blank desolation. Sana Tamreen Mohammed Sana Tamreen Mohammed is a widely published poet. She co-authored Kleptomaniac’s Book of Unoriginal Poems (BRP, Australia) and edited The Prose and Poetry Anthology. She was also featured in a radio show in India. Her poems have been displayed twice in The Fox Poetry Box in Illinois. ** A Book Rests A book rests Reassuringly on my legs Open at God’s promise Raised dots beneath my fingers Touch an arc of colour Red as a bite of crisp garden apple Orange as marigold scent Yellow as burning noonday sun Green as meadow grasses tickling my legs Blue as earthy peppery cornflowers Indigo as plum juice running down my chin Violet as morning glory petals I know these colours because once You helped me discover them And I wonder What is it like to see a rainbow? A book rests Heavy on my legs Anchoring me to this chair As I feel my way Through water to dry land I look up as an olive branch Taps on my window Feel your eyes upon me Upon my coarse, rough dress Dismal like evening inside I smile, Close my book Hand it to you Our fingers touching fleetingly And I wonder As our hands explore each other, what colours do you feel? Alison R Reed Alison R Reed has been writing for many years but only recently took up poetry, and even more recently discovered ekphrasis. She has had several poems published in local anthologies, as well as one in The Ekphrastic Review. In 2020 she won the Writers' Bureau poetry competition. She is a long time member of Walsall Writers' Circle. ** Blind Girl Reading We recognize in retrospect she was a medium like “Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante”, a spirit finger from fairy, that land existing in crepuscular and gloaming, a native Spiritualist. Arranged in a dress of gray ruched wool, she poses in a pyramid of illumination. The brilliant book tilted in useless light gives an illusion of floating, as if her hands possessed magnetism. She fetches messages from beyond the visible, a hint of table tipping, séance prive, tarot dealt on tea tables, smart parlor games. Her face is the vanishing point, rendered rough in the Venetian Mannerist style of oil painted miracles. Still, it reveals her class, born to work. Her mouth is closed, trained to withhold words, servile, silent. Intransigent eyelids shut, absolute. The viewer is asked “How?” her right hand learned reading the same way it can cane reeds and rushing--- touching edges. She whispers each word not pretending to understand. She’s offered no district reverie with Wordsworth--- The Book of Common Prayer. The Communion as if faith was a virtue taught by rote. “Let my prayer be set forth in thy sight...” This irony goes unnoticed in the angelic silence of wings lifting her to stand atop the dark work bench of justice--- her book glowing, she points to each act, each name with servant’s precision. D E Zuccone “ Madame Sosostris, famous clairvoyante” T. S. Eliot, The Wasteland. Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc. New York. 1930 “Let my prayer be set forth in thy sight...” The Book of Common Prayer, “Daily Evening Prayer, Rite One”. The Church Corporation of New York. 2007 As D E Zuccone, I am the author of a volume of poetry Vanishes released by 3A:Taos Press, winter 2020. I have published poems in Borderlands, Water Stone, International Review of Poetry, Southern Indiana Review, Schuylkill Review, Hurricane Review, Big River, Apalachee Review, Deep Water Literary Review, Garden Box. My work has been in anthologies from Round Top, Taos Artists, Words& Art, Mutabulis Press, and Big Poetry Review. I have been a featured reader in Houston, Taos, Los Angeles, and a frequent, grateful guest of Archway Gallery. I am a graduate of Vermont College of Fine Arts. ** Blind Girl Reading Who needs the splurge of silver light over the pages of her book? Her face glides in the night, ponders upon us. Her dress is pleated with black cliffs and caverns that hold a multitude of secrets. She needs neither our darkness nor our light, seeing with the patience of Tiresias and the accuracy of Cassandra. Blaga Angelow Blaga Angelow lives in Los Angeles, California. ** Agneta’s Journals “Who needs eyes when you have The Gift?” Mother’s voice, unbidden, courses through her mind. It has taken whole years for Agneta to find comfort in the gift that Mother (dead, now, for two decades,) has given her, as many as it has taken for her to learn the shape of her blindness: something she’d acquired in the depths of childhood. She has learned how to reach through it with her fingertips, her ears, and (on occasion) the senses of her mouth and nose. And like Mother’s occasional, needling questions, the gift that Mother has taught her demands its own price: twinges of guilt whenever Agneta settles into her reading chair to spend time with her journals. She leaves one open each night, its blank pages exposed. She closes it each morning, wracked with guilt for the cruelty she commits. Each night as she sleeps, she leaves her journal open in her reading place. Each night as she sleeps, ants step across the pages and arrange themselves in neat lines of insect braille. They bite into the paper, clenching themselves in place with their jagged, pincer-jaws, and each morning, before breakfast, she closes the heavy tome, smashing the ants, so that she may have a near-permanent record of what they tell her with their bodies. It may take months for their bodies to harden and adhere, whole, to the pages, and there are entire tomes written by martyr ants she has yet to read. Reading those takes a species of bravery she has not yet cultivated. Her cruelty, she thinks, is plaintive and remorseful. A necessity. The ants understand, or so she tells herself. They never complain. And now, after months of waiting, she dares to read news of her absconder of a son. Osvald has always been inscrutable and aloof—distant and unreachable, even in the same room. There has always been trouble between him and Ulf: arguments…quiet, smoldering threats of pitiless, passive violence. Father and Son were too much alike to get along, and too different to reach an understanding of one another. She’s asked about Osvald, and her ants have sent her query from colony to colony—from ants she’s known to those she’s never spoken to. After months of searching, some six-legged stranger had found her son in a sprawling, foreign city, on the southwestern shore of a vast, alien lake. The air in that city—so the ants say—smells of poison, bravado, and strange electric aethers. It’s all here, beneath her fingertips, all here in the book-flattened husks of self-sacrificed messengers, showing her the life of her son in the orthography of their corpses: of Osvald at home, so far away; Osvald asleep in the arms of his Friend, the dark-skinned one he has mentioned in terse letters to her and Ulf. She’s always known of Osvald’s profound and exacting difference from his father, his cousins, and most other men. Now, as her fingertips caress the cadavers of ants, she has confirmation of Osvald’s honest and inscrutable life…. It is both familiar and alien, clogged with proceedings and passions she dares not consider, even as they’re defined and limned with inscrutable emotion on the pages beneath her fingertips. Now-- —the quiet tread of footsteps draws her from her reverie. Ulf’s familiar scent—like wood and like hair—touches her nostrils and his voice nestles in her ears. Softly. “It’s late.” “I’m finished,” she says, pulling her fingertips from the narrative beneath them. “You’re pale!” “I’m fine. Just a bit tired,” she says, closing the journal and leaving it beneath her chair. Ulf says pointedly inconsequential things as they prepare for bed—redirecting his thoughts, she knows, talking himself out of the questions that he has for her. After a while, and nestled in bed with Ulf beside her, Agneta listens to crickets beyond the bedroom window. An indolent breeze rustles the foliage outside, and there’s tension in the room, as if thunderclouds gather in corners and beneath the bed. She can hear twitchy uncertainty in Ulf’s silence. He knows her habits as well as his own, and she knows that he’s seen her close the journal rather than leave it open. He’s seen her leave it under her chair, and not on the small stand beneath the parlor window. She knows his habits equally well. She touches her fingertips to one another, rubbing them in silence, as if to find some remnant of what she’s read-- …an ant’s account of Osvald and his demi-African friend, nestled together, flagrantly naked, as they slept that night. They were, as the ants have described, an entanglement of intimate limbs. An erogenous scent enveloped them. From the ant’s jarring narrative, Osvald is as tall, as pale, and as skinny as he’s always been. From the ant’s account, his feet poked from beneath the sheet and moonlight slathered his soles. His feet, the ants have told her, were scented with kisses. The floor, the ants have reported, tasted of footsteps, of dancing and of play… —but all she can feel are her fingertips, stroking one another, now. Ulf shifts beside her. His arm touches hers, and he pulls away with a soft jolt, before touching her again. He is awake. She can tell by his breathing. He is curious, she knows, of everything she dares not tell him. “Is there a moon?” she asks. “Yes,” Ulf tells her, softly. “And clouds too.” She wants to tell him that Osvald is okay—not entirely prosperous, but living well enough in an overseas city, knotted with busy streets. She wants to tell him that Osvald is in love and loved in ways at odds with accepted tradition, and that there are geraniums on his windowsill. Instead she presses her arm to Ulf’s, and listens to the sound of his breathing as he drifts, slowly, into sleep. “Will it rain?” she asks, as if she hasn’t heard the weather reports for herself. “Maybe,” Ulf answers, quietly. “But not tonight.” James C. Howell James C. Howell is a fiction writer from Chicago, with a pronounced interest in non-typical, often surreal fiction. Previous works have appeared (under the pen name, "J.C. Howell" in Cafe Irreal, Five:2:One Magazine, One For a Thousand, and other print and online publications. He currently resides in Chicago, for the time being. ** Blind Girl Reading The village children made fun of her as she entered the library with her faltering steps, wearing her usual solemn gray dress, her face devoid of emotion, hair pulled tightly back into a severe bun, her world seemingly empty of joy or imagination.. The children called her stupid and dumb to her face and wondered what kind of idiot she was to even believe that she belonged in a room of books. They followed her to a chair in a darkened corner of the library where she was seated with an open book in her hands and a soft smile upon her face. The children began to whisper about the light that seemed to be shining from eyes that could not see. They watched as she moved her hand across the page, fingers lightly scratching like the sound of the library mice scurrying to and fro. She heard them gasp as if startled as she began to read to them. She described the air smelling like a blend of cinnamon and the promise of rain and how the words felt like honey on her fingers, her senses on full alert, helping her piece together the details in the story that were missing, painting a picture for the children to imagine. Left to right, her fingers connecting the dots, she captured them and they realized then that it was they who were blind, not her. She taught them to see with new eyes and to hear with their hearts. She showed them the magic in a blind girl reading. Karen A VandenBos Once upon a time, Karen A VandenBos was born on a warm July morn in Kalamazoo, MI. Her youth was nourished with books and her writing. When adulthood opened the door, she was detoured to working in health care for 30+ years and obtained her PhD in Holistic Health. She tumbled into the realm of retirement landing on her feet and was reunited with her creative spark. She can now be found contributing to two online writing groups, unleashing her imagination and trusting her pen to take her where she needs to go. Also on occasion she has had a few of her photographs published in Blue Heron Review. ** Blind Woman Reading Bleak House She is my friend, so I asked her once if her sightless eyes enclose her in black, because black was the blankest slate my seeing mind could grasp. No, she said, there is nothing, and I struggled to understand a world of sounds and sensations-- the cool smoothness of the arm of my chair, the car I heard passing on Winton Road, tea so hot that it burned my mouth-- I tried to imagine a world without light, a world with no colour, no black. Now, as evening dims the room, she opens the Braille book on her lap. Her moving fingers take her to London, where November fills the streets with mud and smoke from chimneys coalesces into a soft, sooty rain. Like every reader, she takes it on faith that shadows of clouds glide over moss, portraits of the dead glare out from frames, and the moon offers a cold, dark stare Catherine Reef Catherine Reef's poetry has appeared in The Moving Force, Visions International, and The Ekphrastic Review. She is a poet and an award-winning biographer, whose most recent book is Sarah Bernhardt: The Divine and Dazzling Life of the World's First Superstar. Catherine Reef lives and writes in Rochester, New York. ** A Blind Girl Reading 1905 The blind girl. You could not leave her alone, could you? One rendering, not enough. One painterly elucidation, not enough. Seven years later you’ve returned, your intent now honed, sharp as a blade. Yet, Ejnar, I am puzzled. I ask, was my puzzlement your intent? That I should sit on the edge of that blade? I look. I gaze. A blind girl reading. My eye wanders over the paint laden surface as over a barren field: the stiffened grey folds of her dress, the pallid skin, the heavy tome upon her lap. I am torn between ascending that deftly obscured ladder over there on the left or lingering in this claustrophobic crypt in order to cull, from your chiselled image, meaning. For you – symbolist poet of paint – you are nothing if not a painter of meaning. But let us go back to that other painting. Your first. You are 26. You place your sightless subject in a landscape somewhere near Gjern. A river coils through meadows, sheep graze, the sky is ablaze with light. You mesh the dark slate dress of the blind girl with the hue of surrounding hills to tell us: she is one with nature. She is not apart. And her hands; her hands are elegant. Her elongated fingers tenderly stroke the pale blossom of a dandelion – most plebian of flowers. Her head tilts, acquisitive, as if to listen to her own touch, sensing the world through fingers that gift her the world her eyes cannot. Your symbolism clear. Your image uplifting, redemptive. But here! Here is another story. Blind girl reading. We are entombed in a darkened vault. You invited us down the ladder. Closed the hatch. And, now, how precisely you choose your inscrutable pigments: raw smoky umbers, liminal greys, soot blacks, the most anemic hues of flesh. Did you weep over the paucity of your palette – grasping in your soul the tragedy of a colourless world? This second painting – hanging now in the museum with the first – garnered rave reviews, soaring accolades: your poignant use of light as metaphor; light cascading over the blind girl’s head, her hands and upon the open book heralding, symbolizing, celebrating imagination, words, language. And thus meaning! Which this blind girl grasps by pressing the soft pads of her fingers over the raised matrix of dots. Coded shapes felt and the world opens! But where, then, the joy upon her face? Where the lips slightly turned upward, as if to say, ‘Ah, yes, I understand?” No, her illumined face floats, a beheaded mask hung upon a curtain. Awkward siren of interiority, draped in grey, shorn of adornment. Mouth pursed tight, eyes cast down. And where the transparent blue of veins throbbing under the skin, the caressing fingers, the soft pink flesh stroking the brailled page like a love letter? Nothing. Listless phalanged limbs. Stones upon paper. And the book strewn across her lap, the lifeless weight of it. And the ladder. Only the lowest rung lit. Could she make her way out, this blind girl, with this dearth of light from above – not the merest glimmer? You and I, we will not stumble. We will manoeuvre nimbly through the dark. But her? Blind girl reading? She is trapped in your shadowed lair. But why linger on darkness you ask, when you have bathed the blind girl in translucent light? Do I not understand the metaphor? Do I not grasp your intent? No, I do not. And you know the saying, Ejnar: we paint only ourselves. You have anchored down this base note metaphor of interiority before which I stand as before a closed curtain. Did you hope to convey the inner joy of reflection, the solace of imagination, the blind girl’s redemption? Or perchance your own? No. This cell is barren. This blind girl, bereft. But then, you will accuse me: “You paint only yourself!” And so, we are abandoned in this liminal place. Between conscious intent and hidden desire. An edge. Sharp as a blade. Victoria LeBlanc As artist, writer and curator, Victoria LeBlanc has worked in the cultural community for almost four decades. She has contributed to over 50 publications on contemporary Canadian artists. As a visual artist, she has participated in solo and group exhibitions across Canada. Her creative practice is inflected by an ekphrastic impulse, a dialogue between drawing/painting and writing. In 2019, she published her first collection of poems, Hold. Forthcoming, Mudlark, a series of meditations in paint and words on a ‘path by a river’. ** Ignite Every day I feel my way beyond lock, door, key, window shut on advancing cold. Out of loneliness I reach. You urge me to try Kindle. Flutter bookmarks to the floor. Let a tablet float on a surprised chest .I can’t. My fingers need paper, words that float on inked arcs. Today it was the Swedish mystery of a murder on water, a motorboat, chains, and skerries. Tomorrow the dressage horse of a little girl’s dream. I cannot fall into a screen. I’m papered with fictions. I love being papered thusly with memories beholding to a shelf. However plain I am, however homespun, I turn a key, burst through in sunlight with women playing violins, kneading bread dough into pretzels for sale at the fair, admiring snow sparkle on pine. This, the diary mind that learns the difference between caiman and alligator. Fingertips afire with discerning. Tricia Knoll Tricia Knoll is a Vermont poet with a large collection of books of poetry alphabetized on shelves, reading for plucking out to read. Her two recent collections include Checkered Mates (how relationships go well or sometimes not so well) out from Kelsay Books in 2021 and Let's Hear It for the Horses from The Poetry Box in February, 2022. Website: ** Missing Lola Elong (Grandmother Consuelo) I wish I had held your seeing hands stretched ahead of you, feeling the wall as your feet glided toward the stairs, as you gripped the handrail with two fists, landed one foot on a step then waited for the other to join the first, carefully, confidently, step by step until you reached the bottom cement floor. You inched forward, left palm reaching, brushing the wall until it found the door. You stepped out, arrived at your chair by the kamias tree, sat in the sun. I wish I had listened to your stories of planting trees--kamias, santol, manga, buko--how before you became blind you used kamias fruits to sour the broth of sinigang with shrimp or fish, garnished with tender leaves of kangkong or sweet potato (so delicious on boiled rice dabbed with fish sauce and chili), or prepared kamias chutney. I tried to make the fruits chewy by soaking in apog solution prepared from wood ash, mixed with water, filtered; mistaking apog (limestone) with abo (ash). My experiment failed; the chutney was inedible, ugly. I wish I could have spoken to you en Español, like my brother who had you as Spanish-language partner. Your words clear and resonant, spoken like the queen I imagined you to be when you combed your hair, waist long but thinning at the bottom. After lavishing the tresses with fragrant oil—prepared by evaporating coconut cream then separating the clear liquid from the mouth-watering latik--you moved your antique comb from forehead to hair tip, starting on your left, collecting the hair snagged in the comb in a pouch to make into a hair piece, adding volume to the neat bun on your nape put in place by your seeing fingers expertly manipulating hairpins. I wish I had sat down with you, recorded your stories of Spanish-speaking Filipino households, life at the turn of the twentieth century, Americans replacing Spanish colonizers, the second World War, my distinguished ancestors; your sister whom I wish I could have known, who died young, long before I was born, whose daughter was my Mom, whose youngest son was the uncle who took care of toddler me, who, until he died, teased me—threatening to hang me upside down from the ceiling when I was stubborn—then laughed and gave me a hug. I wish I had answered whenever you called out, “Who’s there?” I was hoping you wouldn’t hear me, avoiding your incessant questions, hurrying to do whatever, just not to get stuck with you. I was a foolish teenager, unaware of the gem that you were. I wish I had known you when I was old enough to appreciate you. Ann Maureen Rouhi is Filipino by birth, Iranian by marriage, and American by choice. She is a reluctant writer but tries nevertheless because she has stories to tell. ** In the Theatre Behind Her Eyes (Summer With Her Roses) "Autumn with her lamb, spring with her blossom, Winter with her bundles of holly, summer with her roses..." Kerry Greenwood Her fingers tracing lines with symbols she read inside in winter, waiting for warmth in the garden when the sun was real to everyone in the house -- flames of light at a magic hour when, she'd read, transformation was possible. She listened to the voices of the children playing near the barn their laughter outside the door; and inside, the animals she loved waiting for her to come, for her fingers to understand them. She was older now, a young woman when the artist asked her to sit for a portrait -- a serious picture, someone commented later, all in grey tones the way he must have thought her world looked defined by blindness. He had been patient, at first, as with a child, having her feel the brushes; was surprised when she said her father had put braille wrappers on colored sticks and held her hand so she could draw. It was their game, matching colors to his words, stories happening on paper. She preferred fairy tales, The Little Match Girl by Hans Christian Andersen. She imagined that child, dressed in rags, freezing on a corner near Staerekassen as well-dressed people left the theatre after the sun had fallen through the snow, into darkness no different from the day as she knew it. "Does the world change at twilight?" she had asked and the artist had answered, saying it was a time, like sunrise that showed the colors hidden in the sky... "Like what I can see behind my eyes! How I see the garden! I'd wear a flower crown there, on May Day and touch the leaves -- new leaves -- so tender if I rub one with my thumb I can smell the springtime. Why do people who can see with their eyes ignore so very many details? When I was younger, my brother put me up on his saddle and described everything in the landscape my fingers find in Braille. My hands say my sisters are pretty, and I have felt all of my features asking myself if I am ugly because my eyes can never open. Then I remember how my sister tied a thick string to me when we played Blind Man's Bluff. She put a scented handkerchief over my blind eyes so I'd be like the others and whispered we would hide in the very best place so no one could find us, and we would win; the string just in case I was misplaced in the woods. It was summer with her roses (fall coming soon, with her lamb) and I'd been allowed to read outside when I heard my sister laughing, picking roses so she could shake petals all over me -- the family's Ugly Duckling. Behind my eyes, river water filled with white birds and I could smell the horses, with the boys, always running and riding; and the roses; how the air whispered night was coming, real and all the swans were swimming." Laurie Newendorp Laurie Newendorp, honored many times by The Ekphrastic Review's Challenge including being nominated for Best of The Net, lives and writes in Houston where she received second place in The Houston Poetry Fest's Ekphrastic Contest. Her recent book, When Dreams Were Poems, 2020, explores the relationship of art to poetry. Writing about Nielsen's Blind Girl Reading (he later painted the interior of Staerekassen and flower crowns) brought to mind the magical reality of Jorge Luis Borges, a writer whose imagination wasn't impaired by the fact that he was blind.

** Blind Date The book is open, but the eyes are closed - Nielsen’s somber symbolism here cannot, in all mimetic justice, sign a verbatim schism from this crying realism; yet, in perspective, either way, she appears a live study of a Cappadocian cave church murals, where the images live in allegoric night having suffered a chiseled destitution of sight. 1. Her jet black dress is the insignia of the laps. The tome’s luster overwhelms her charcoal lap: will she find her way in this cul-de-sac ploy? Upon her ebony silhouette the folios dawn as rays-seeded realm, designed faithfully to nurse the pilgrimage of her hand. Her deductive mind is a novice scout in the lines, fully immersed, following the patterned route, as the Camino gathers pace. 2. Alas, a Checkpoint Charlie for aspirants – facing the emotional churning of the ocean – under the eyes’ eclipsed sun, in the eye of the storm of lines, riving wave after wave of signs to un-tag the energy from the matter and cohere the zeal of the salt – mighty! Nielsen’s mastery here hangs on the artless gravity of the pale-shy hands-on act, he so gracefully set, like a lover caressing the beloved but aiming to embrace the apparition of spirit streaming through the blinding stained glass window of loving. 3. The pilgrimage enters the Mecca of comprehension. A communion vibe stirs between finger and brain, propels along the leaves’ patterned terrain, pulls promptly the perceptual trend welds the throbs of the cryptic formations and at the luminous altar of the mind derives the connotation. This blind date takes a flash of reality, an eon of symbolic parity. They are forever congregated in this Nielsen-Braille temple to celebrate the birth of each word and in the conversion of symbol to meaning may fathom the inner witness of their kindred beginning, which, the seeing readers can’t obtain, but can know how much we don’t know. Ekaterina Dukas Ekaterina Dukas studied and taught linguistics and culture at Universities of Sofia, Delhi and London and authored a British Library publication on Mediaeval art. She writes poems as a pilgrimage to the meaning and a number of them appeared in Ekphrastic Review, Ekphrastic Writing Challenge, Poetrywivenhoe, Beckindale journal. Her poetry collection EKPHRASTICON is published by Europa Edizioni, 2021. ** I Want to Go Home As the evening chills rise And the darkness grows. My fingers breathing the way Through the maze, a game that I played Of guiding little bunnies find the carrots, The mice their cheese and A spider her cobweb. I rise to the sky Painting it piece by piece, Red, blue, black and white. I ride into the woods tearing the breeze, Birds singing, each becoming a friend Leading to the world inside of me. Dreams welling with each touch Building a new story altogether As the evening falls and the darkness grows. I hear the cars go past taking the riders home. The quivers numbing my fingers, slowing their pace Feeling the pain between the words. Abha Das Sarma An engineer and management consultant by profession, Abha Das Sarma enjoys writing the most. Besides having a blog of over 200 poems (http://dassarmafamily.blogspot.com), her poems have appeared in Muddy River Poetry Review, Spillwords, Verse-Virtual, Visual Verse, Sparks of Calliope, Trouvaille Review, here and elsewhere. Having spent her growing up years in small towns of northern India, she currently lives in Bengaluru.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Challenges

|