|

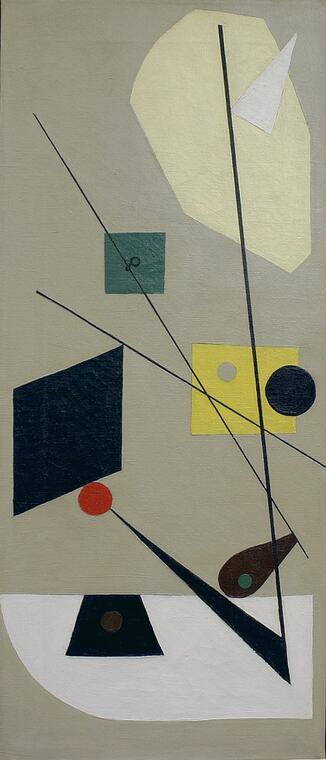

Abstraction with Red Circle I could have been anything-- a cloud of ever-changing form, a loose sparrow feather trembling in the leaves-- that moment of weightlessness, that yearning. I could have been water in a glass, shattering reflection, instead of ice melt pooled on frozen clay. But the rising moon held me till daylight burned me. The sun raised blisters on my skin. You see? This world is not all sweetness. I could have closed my eyes and seen nothing. Siberia or the sand, what called me? The cold. What kept me? A red balloon. What tied me to the earth? The sky, relentless weight of it. Patricia Hale Patricia Hale is a poet and collage-maker. When words won’t come, she tears up things to create something new. She is the author of the poetry collections, Seeing Them with My Eyes Closed, and Composition and Flight. Her prize-winning work appears in many journals and several anthologies, including Forgotten Women, Railonama, Encore 2021 Prize Poems, and Waking Up to the Earth: Connecticut Poets in a Time of Global Climate Crisis. She lives in Connecticut, where she serves on the board of directors for the Riverwood Poetry Series.

0 Comments

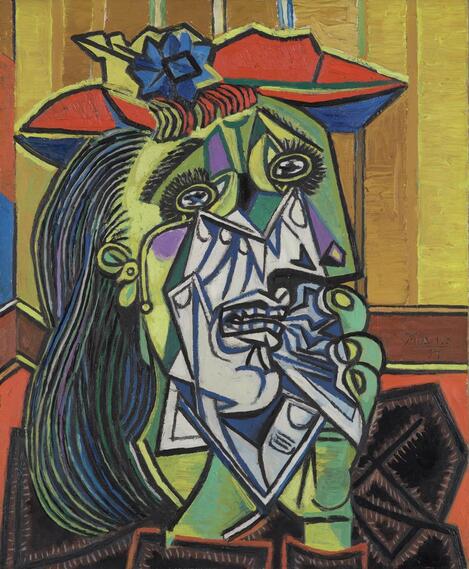

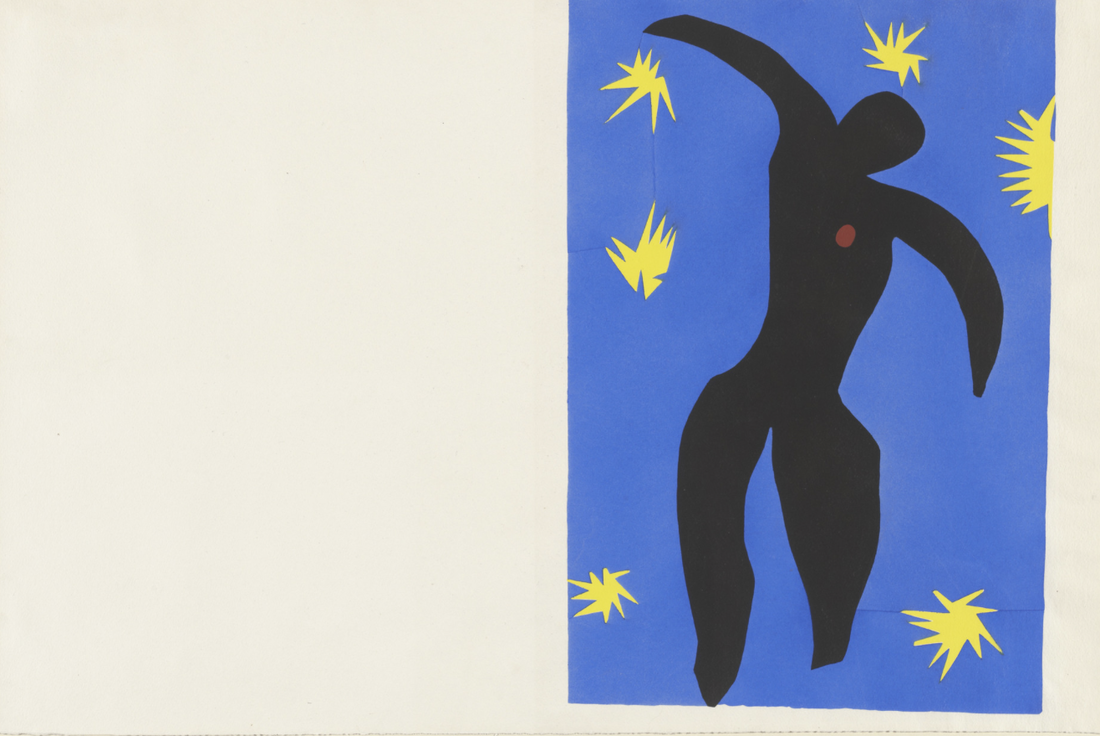

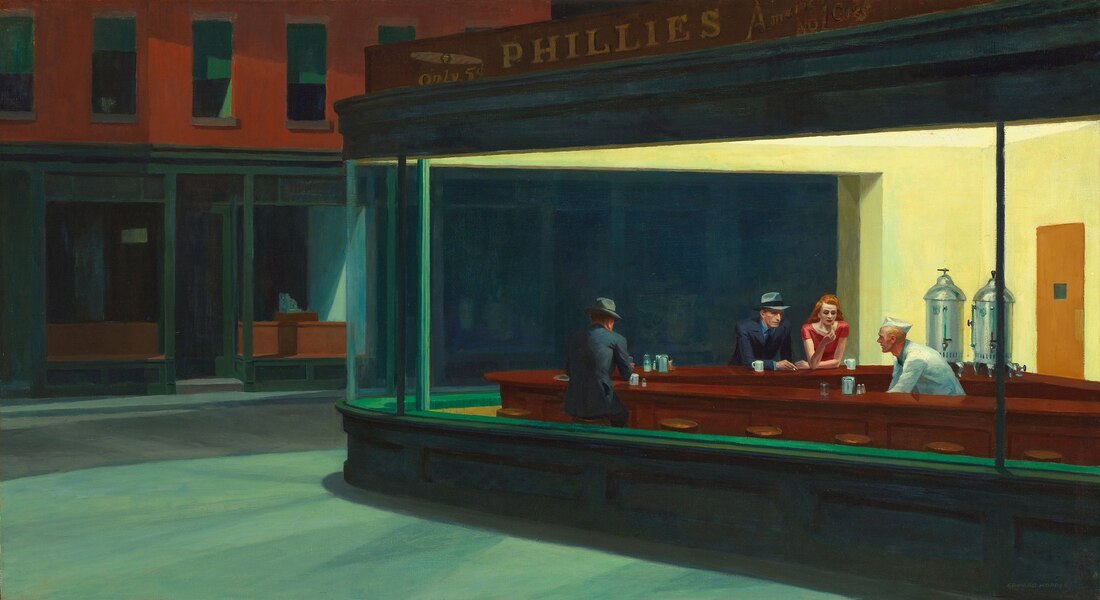

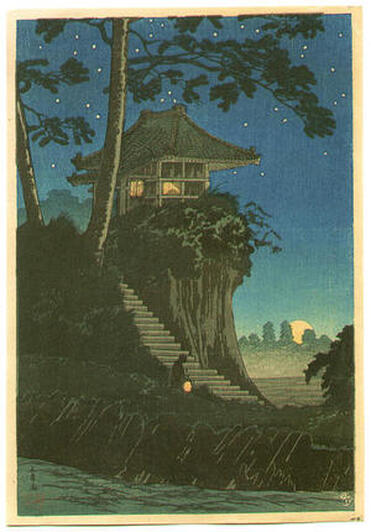

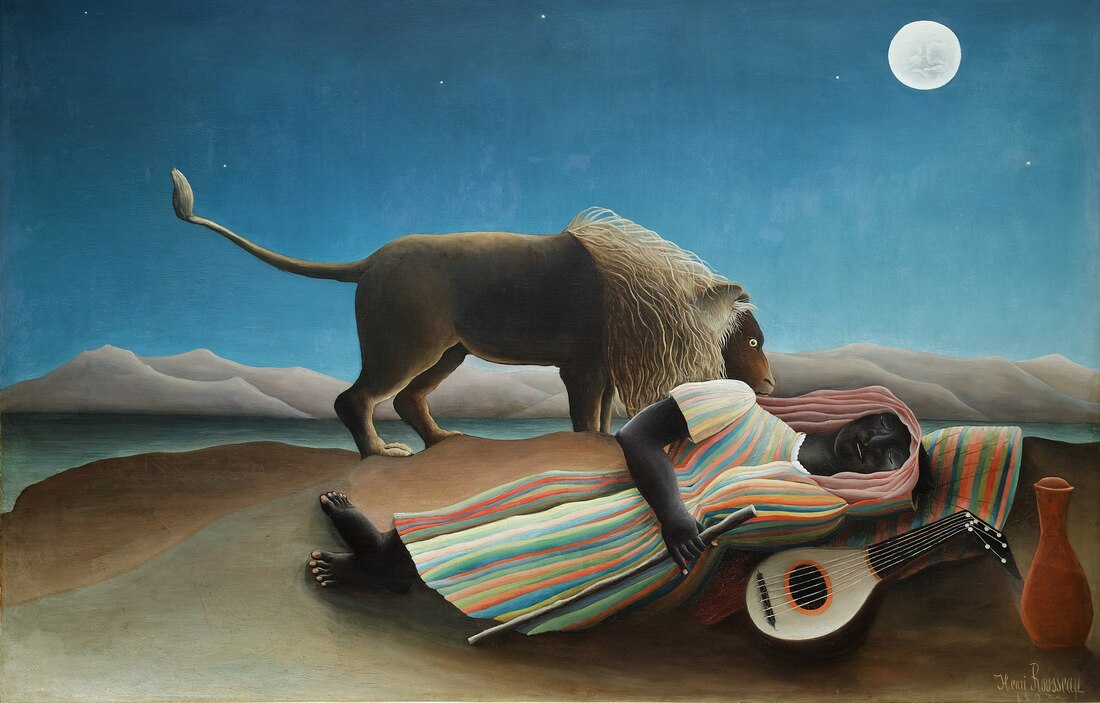

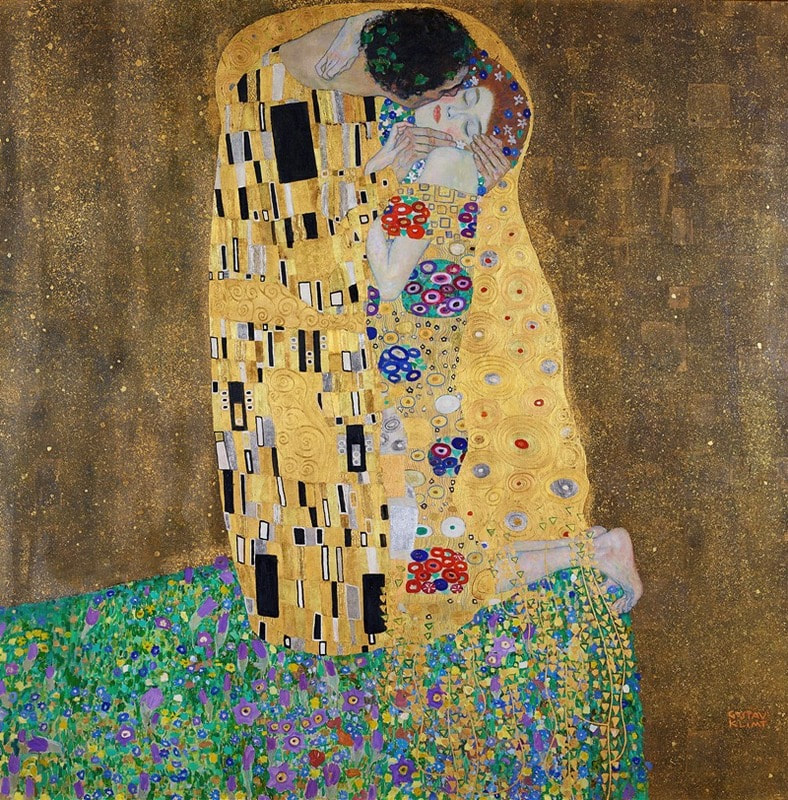

This poem is inspired by Her Room, by Andrew Wyeth (USA) 1963. https://collection.farnsworthmuseum.org/objects/1251/her-room The Artist Has Laid Down His Brush And is Done for Betsy Wyeth The same curtains blowing at the window, the same wallpaper, but peeling a bit now, faded and water-stained. The conch shell, empty as his chair, blows the same sea across the cove of your ear as you lift it to your head like before. Bring home the gulls to your roof with a long low whistle from the conch, bring neighbors with casseroles, bring the dog from his lapping the melt of ice in the dooryard. Bring your same fingers to draw the curtains aside. Step through each room, their creaking floors like old bones, careful and slow. Watch the leaves of his sketchbook ruffle in the breath of the open window as if he’s thumbing them, deciding which drawing or sketch wants paint today. The same scenes are never to be the same without his careful eye. The conch will go silent, the chair unmoved and dusty. Somehow a shaft of sudden sun slanting the floor won’t be the same kind of light he saw. Even the dog will not snore the same. People will call and ask of you now that the artist has laid down his brush and is done. You won’t answer because you are not the same as you were just yesterday. They will ask for some small memory of your time with him and you will say, the wallpaper holds all his secrets. Carol Willette Bachofner Carol Willette Bachofner is an award-winning poet, memoirist, photographer, and watercolourist. She served as Poet Laureate of Rockland from 2012 -2016. Carol is the author of seven books of poetry, most recently Test Pattern, a Fantod of Prose Poems (Finishing Line Press, 2018). She is at work on a mixed genre memoir, A Life Beset With Words. Her poetry has appeared in numerous journals, such as Prairie Schooner, The Connecticut Review, The Comstock Review, Cream City Review, as well as in the anthology, Dawnland Voices: an Anthology of Writings from Indigenous New England (University of Nebraska Press, 2013). Eve Stands in Front of The Weeping Woman The splitting hurts. She lifts her hands & holds her own face, can almost feel the silvery tears, the edges he's cut, the world of a woman sliced into triangles. Are we all gray inside? & how many sharpened angles unlived? Red hat with a blue bow. Packaged grief, she thinks as she moves closer. Picasso walls her in: a woman weeps, her silenced eyes haunting or haunted. Sarah Dickenson Snyder Sarah Dickenson Snyder carves in stone & rides her bike. Travel opens her eyes. She has four poetry collections, The Human Contract (2017), Notes from a Nomad (nominated for the Massachusetts Book Awards 2018), With a Polaroid Camera (2019), and Now These Three Remain (nominated for the Massachusetts Book Awards 2023). Poems have been nominated for Best of Net and Pushcart Prizes. Work is in Rattle, Verse Daily, and RHINO. sarahdickensonsnyder.com Pentimento Each layer of myself hides beneath a later paint. On the canvas under Picasso’s The Old Guitarist, I’m the old woman with bent head. No, the young woman who nurses a baby. Much is blue. Though even that fades. See the blind musician. His face, thinned-to-skull, still hints of handsome—aquiline nose, lifted cheekbones, ah the lips. Could I have kissed. Like a man I once knew. Our mouths lingered, eager. The slow burn an opal blue. Don’t look away. Boney fingers, the emaciated frame. Death’s pentimento beneath the still alive. Look again. His left hand frets the chords. He tips his head to listen. Joyce Victor Jazz Flag A silhouette swims across the starry night, darkness in a midnight blue backdrop; A splotch of red where the acrobat's heart is, representative of a dozen of the best. And above in the velvet depths of openness, we see those stars Sirius, Vega, Cassiopeia, as well as Parker, Gordon, Davis, Coltrane, Hughes, Kerouac, Ferlinghetti and Corso. Like officers of the line, those heroic artists just kept on fighting this society's emptiness by endless improvisation—all emanating from a red splotch of the acrobat's heart. Each session—a variation on the ordinary, but at the same time something new, and we raise this flag just after sunset and listen to changes that are always true. DH Jenkins DH Jenkins' poems have appeared in Jerry Jazz Musician, The Tiger Moth Review, The Global South, Bellowing Ark and The Wave. For many years he was a professor of Speech and Writing for UMUC-Asia, living and working in Japan and Korea. He now lives in New Zealand and enjoys hiking in the Southern Alps as well as scuba diving and snorkeling in the Pacific Islands. Still, Life: 1950s What can be said to the perfect mother sitting stone still in the 1950s living room where you never really lived? Poised, not reading words you cannot say, syllables that might crack the stone sitting room? Still in the 1950s, she smiles beautifully but doesn’t hear words you cannot say, syllables that might crack the polished stairway you creep down. Comfort? There is none. She smiles but doesn’t hear grief, pain, anything slightly unpleasant. Still, you seek comfort, creep down the polished stairway. Maybe this time she will turn her head, believe your grief, pain. Instead, anything slightly unpleasant goes unsaid. You protect her, this beautiful sculpture, who might, this time, believe you, turn her head and feel your scowl. It could destroy her, this beautiful sculpture. The unsaid? The child protects the mother, who sits stone still in her 1950s living room. Don’t allow her to feel the scowl that would destroy her. You cannot say the words that might crack syllables, alter the 1950s room, her life. She sits still as stone. What can be said to the perfect mother? Your syllables might crack her. Your child words could destroy her poise, uncover where you really live. What can be said to the perfect mother? Poised, she smiles beautifully but doesn’t hear. Why destroy both child and mother? You’ve never lived outside cracked words you cannot say. Silent, still. ** This poem was first published in Shiuli. Poppies and the Cedar Tree What else could they be but planets and sun, coral glow of bloom tattered against dusk’s uneven waves of bark, slowly peeling to reveal the underneath? Tangled temporarily in brittle twigs, they do not die but transform: bright miracles of surprise orbiting, cedar’s ashen fingerbones that release and heal with orange what rises and descends, what keeps circling in this sphere of sky, of us. Two Poppies and the Fence The best of neighbours, they ignore boundaries, inquisitive countenance peering over into what we claim as ours—rectangle of land, sky delineating what is paid for and possessed, which is why, at day’s end and beginning, we need them, each wide eye and petaled chin trespassing on morning coffee, on evening strolls around the cloistered yard that need their joy, their bright exuberance of orange, unsolicited and bold. Hope Is the Thing with Feathers (after Emily Dickinson) The curlew is the thing with feathers, is the beak wildly waving wide ribbons that hold back the strands of storm. That’s the thing about curlews, about hope. Red sky in the morning....Warning and delight intersecting, flag-like ribbons curling into another day maybe. The curlew is the thing. Even in the middle of a hurricane, even on a fragile bough while earth’s vast tornado of despair keeps widening, widening, the curlew is the thing with feathers, is the beak wildly waving its frayed but flapping ribbons of persistence, of hope. Red sky at night, sailor’s delight. Sky widening, widening into curlews, into hope. That’s the thing. ** This poem was first published in Valiant Scribe. The Witnesses after the 2018 wildfire in Curlew, Washington Near the confluence of Long Alec Creek and the Kettle River, the curlew watches its namesake-- town of one hundred-- as residents stare toward the west, inhale fear. Smoke rewrites the sky where the curlew once flew. Flames attack its map and habitat. Ridgelines pulse with what is singed: feathers, pines, mountains, horizon streaked with regret and the burnt promises of those not there to witness, the incineration of branch, the contagion of spark, the long, slow burn of loss. O Curlew and curlews, obscure enough to hide once within these safe acres, even you Grief has found, even you. ** Marjorie Maddox ** This poem was first published in Valiant Scribe. ** Professor of English and Creative Writing at Lock Haven University, Marjorie Maddox has published 14 collections of poetry—most recently Begin with a Question and the ekphrastic collections Heart Speaks, Is Spoken For (with Karen Elias) and In the Museum of Her Daughter’s Mind, a collaboration with her artist daughter, Anna Lee Hafer (www.hafer.work), and others. She also has published the story collection What She Was Saying and four children’s books. Two new collections of poetry are forthcoming in 2024. Please see www.marjoriemaddox.com Dr. Karen Elias, who taught college English for 40 years, is an artist/activist, using photography to raise awareness about climate change. Her award-winning work appears in private collections and galleries. She serves as board member of the Clinton County Arts Council, as membership chair, and as curator of the annual juried photography exhibit. In addition to Heart Speaks, Is Spoken For, collaborations with Maddox have appeared in such literary, arts, or medical humanities journals as About Place, Cold Mountain Review, The Ekphrastic Review, The Other Journal, Glint, Ekstasis, and Ars Medica. Elias, also a playwright, has had work chosen by the Climate Change Theatre Action and performed in eight countries. Rothko No. 5 / No. 22 “Close your eyes and you'll see” The heat-haze Off the red-hot highway That grows across this Painted desert Like a blood-soaked bed of Leafless roses In a sea of light that Shimmers And a box of sand that Swelters “Yes, I see, I said” Combustible pools of Oil and turpentine Chasing Sunburnt turf “I sense your anger, but you are not mad” No one could destroy such Magnificence No one, not even he, wields Such powers Under layer upon painstaking layer An ocean roils Obscured By gleaming gold and sand “A-wash this desert,” I cry “Oh, please wash it clean!” And above the horizon A gate opens With a single stroke "Mine eyes have seen" "Still gazing inward," he replies When the desert floods Is it providential precipitation Or human tears and blood The year was 1950 We’re still counting and Watching the gate A madman’s mushroom cloud And when the shockwave crosses The highway centerline Razing everything in its path “Promise me I'll be gone I have no heir, no next of kin You cannot hurt me then” Steen W. Rasmussen Steen W. Rasmussen is a native of Denmark and lives in New York City. His interest in writing is rooted in many years of songwriting. His poems have been published by Sparks of Calliope, Lothlorien, Dadakuku, and Voices of Poetry. Nighthawks More coffee, ma’am? No thanks. Why do you keep looking at that thing? What do you care? It’s just something to remember it by. Yeah, I’d like to forget about it. A little more water, please. Sure thing, Mac. Awfully damn quiet tonight. ‘Cept for your yakking. Come on, Jimmy. You said we was going to have a nice night. Well it’s after midnight, so the night’s over. (Cough.) Got an ashtray? Let me wash one out for you. So you think we’ll get into a war? Gloria, Roosevelt says we gotta be prepared and learn to live with lights off in case of attack. I hope you don’t get drafted, Jimmy. Me neither. Moonrise at Tokumochi My master is late. I am waiting for his return. The lantern burns low. A thousand stars decorate the night sky as the moon peaks through the trees. Inside the house the low light beckons you home. Hot tea and a bowl of rice to welcome you. The Boulevard Montmartre at Night Grand Hôtel de Russie 13 February 1897 Dear Lucien, I have painted the boulevard in snow, rain, fog, mist and sunlight, in the morning, afternoon, and at sunset. The other night, I wanted to capture the new artificial street-lights reflected on wet pavement. I used clear Yellow for the old gaslights and in shop windows and the oil-burner lamps on cabs… then Cool White for the new electric street-lamps lighting carriages, buses and people and shops. It’s tricky to capture the new lights, but these are a wonder, illuminating and awaking Paris from its sleepy nights alive with energy and life. (Not unlike the noisy couple cavorting in the room next door!) Papa Fishermen at Sea Dylan! Haul in the nets, lad. Bring the lamp closer so I can see what we’ve caught. Cod or flounder? Watch the rocks! It’s not called the Needles for naught. Looks like a bit of both. Thank the Lord we’ve got the meager moonlight to see some money tonight. Pull with me, Connah! I canna bring in the net alone. Ah, it’s a night for rollers it is. That Mervyn’s boat afar? I canna barely see you, Dylan, but it looks like his dory. I’m sure he’s left some fish for us. He’s the laziest lembo in all of Wales. The Sleeping Gypsy The Lion Smells like meat. Asleep. Not dead. Looks like stripes. Watch for stick. Tail up. Stay back. The Gypsy I am dreaming of walking across the sands carrying a song in my mandolin for my love who makes me smile in the morning with all the colours of my djellaba. Starry Night Whorls of stars and planets spin around in my head lighting the sky while the little town sleeps the good doctor has let me out in the field behind the asylum to capture the panoply of the heaven whooshing above me and the one dead cypress Larry Oakner During the two years of the pandemic, he led a group of "Senior Poets" in a poetry Zoom, and self-published another chapbook entitled, Unwinding The Words last year. He has also had poems published in other online sites. Recent and upcoming publications include Blood & Bourbon, Burningwood Literary Journal, Nassau County Voice in Verse, Ghost City Review, and Red Wolf Press. Gold Call us debris, the whorls of a kiss. There’s no verbatim for this lit, shared space. Maybe we were each a TESS in orbit, trailing the universe for inhabitable bodies beyond our own. A brave science, mining for glimmers in the dark. How many hours have we sat and mapped it out, nattering on sweet trajectories under night confetti? With golden nothings scribbling by the fence – chestnut-brown anemones erupted on the bed. Vines in the crimson dusk kinked on our naked feet. Do you see the flowers sprouting from our crowns? Before you, wise ones bade me only kiss where butterflies throb. This! Generations of ranunculi made the pattern in our kiss. So lush, almost obscene. Do the neighbours glimpse our quilted pornography? What about these stars, once silvery, set high? Now they’re honey-smattered low around our gamut-of-yellow sheen. Linda Kohler Linda Kohler lives and writes in Kaurna Country, South Australia, with her three people and a lorikeet. You can find her at lindakohler.com. Snowscapes Yesterday’s filigree branches and low, grey clouds promised this… …I wrote a haiku A near whiteout …I wished My fondness for how falling snow… Tamps down the city’s jangling distractions Fond even of how it can render me invisible to everything on the other side of my window… Or am I? Most of all how snow lends plot, vivacity to the view… The snow-spangled roof across the street puts me in mind of Hiroshige… Hiroshige, Master of Rain and Snow I could be Hiroshige’s cat gazing out another window overlooking the rice fields of Asakusa Better still, his fine eagle swooping and diving over the marshes of Edo Bay To be a bird right now would suit me fine…soaring above this conglomerate of rooftops, circling spires, dodging towers, scoping gorges For a glimpse at the ripples of sidewalk life… Best of all to touch down on a lightly-dusted ledge or shoulder of a gargoyle… Watch the tiny crystals emerge from a snow cloud Float, twist, turn, collide, tumble and take shape, facet after facet, branch after branch into six-pointed star-ness… Or melt. These would not be Hiroshige’s snowflakes… His dot the sky like constellations, eliding the details; more intent on the aerodynamics of imagination. Almost without notice, the squall beyond this window has subsided—the atmosphere no longer in motion… The roof across the street does not evoke Edo. I am not cat or bird… In the blink of an eye I have been jolted from one dream world back to this one, Fitful, yet poised as always to drift ever so easily into the next… the next… and the next… . Kay S. Lindsey Originally a visual artist, latterly, a poet, Kay S. Lindsey enjoys collaborating with creatives in variety of disciplines, most recently, a cellist. In 2001, her poem, “The Origin of Applause,” written in collaboration with a visual artist, was transformed into a public art work and permanently installed at the Cannon Center for the Performing Arts, Memphis, TN. Her work has appeared in journals, several anthologies and chapbooks, online and performed. A Washington, DC native, she’s called Philadelphia, NYC, L.A., Sacramento, Hawaii, San Antonio, Memphis and now Hyattsville, Maryland, home. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|