|

Velasquez’ Self-Portrait Surrender of Breda I Velasquez painted his self-portrait in Surrender Of Breda just behind a massive horse whose rear And flank dominate the lower right of the canvas. Sporting a light grey hat with white and ruffled plume, Velasquez painted himself with a white-laced scarf Around his neck draped over his light grey coat. His grey coat is softer in palette than the armoured Ambroglio Spínola, Genoese general over the Spanish Army, shown accepting the keys of the city of Breda From Justin of Nassau, the Dutch governor. Elegantly dressed. The painter shaped his own face, hair, Moustache, and grey cloak with a soft roundness Set off from the brown lances pointed skyward And forming a vertical lattice in the right background. II Velasquez painted his face a lightly ruddy glow With a brown goatee and upturned moustache. Velasquez painted his left boot just below and behind The right gold stirrup set below the darker browns Of the horse’s right flank and even darker strands Of its mane. From the edge of the canvas, As if holding the horse at bay, keeping himself In the picture, he eyes the viewer. His self-portrait in the right border mirrors His portrait of a young gun-wielding Dutch soldier Whose black eyes seem even more transfixed On the viewer. III What is the folded white paper Painted in the lower right corner, Lying atop brownish-grey rocks, directly below Velasquez’ light brown boot and the dark brown Hoof of the horse? Why this white paper Where Velasquez might have signed This massive memento of the surrender at Breda? Why left lying on rocks, unsigned, Like the folded blank piece of paper On the bottom left of his Philip IV On Horseback, finished the same year, 1635, 10 years after the Dutch Established Fort Amsterdam as the capitol Of New Netherland, 27 years after Don Pedro de Peralta founded the city of Santa Fe, New Mexico? John Beall John Beall’s first book of poems, Self-Portraits, was published in 2019 by The Finishing Line Press. The poems, “Self-Portraits” and “November 22, 1963,” were awarded the Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Prize in 2016 and 2017. His poems have appeared in The Henry James Review, Slant, MidAmerica, and Poems for Hemingway and Paris. His poem, “View of Mount Atalaya,” appeared in the summer 2021 issue of Slant. His poem, “Goya’s Self-Portrait at the Prado,” is due out next year in the collection: Song Up Out of Spain, to be published by Clemson University Press.

0 Comments

The Banquet of Cleopatra Not another woman in sight, unless you count the hazy onlooker in the balcony. You sit in a world of men, and your pose, despite your delicate fingers as they suspend the pearl above the glass, your hand on hip, limbs akimbo beneath swathes of satin, your pose a military one. Your lover would restrain fire, a man in armour Unmanned by this pseudo-feminine putsch. All men around you. Not one friend. Even the dog, another onlooker, anticipating meat. You play hard, Cleopatra, Daughter of generals tost by the gods to the throne. In this one moment of glory you command and subjugate the men who will soon close in on you, they and their dogs breying and fighting for fresh meat. Anita Jawary This poem was first published at Litterateur RW, 2022. Anita Jawary is a Melbourne artist, writer and poet as well as a volunteer docent at the National Gallery of Victoria. Anita began writing poetry in lockdown 2020 and has published in Be Guided by Art, Songs of Eretz, Poetica Review and Jewish Literary Journal. Her work has also been broadcast on Pier-Glass Poetry and TBI Daily Daven. Her flash fiction series, The Dickensian Challenge with her own art work, has recently appeared in Jewish Women of Words. You can find Anita at www.thedickensianchallenge.com Red Canna The painting is red. And other shades, too—corals, persimmons, rusty yellows, all layered against each other, ripples of colour that bloom out from a cool white vertical centre. But red—crimson—is its predominant mood. Something open and raw, bursting through a seam that reminds me of the sky, of clouds backlit in azure. I eye the print for some time before it occurs to me: it’s a flower. The room is positively overflowing with them. Paintings, prints, and photographs, all in vibrant hues and thick black frames. They hurt my eyes. Small statues or figurines—I don’t know the word—inhabit the room as well, set haphazardly onto tables and little desks; they depict people stretching or dancing, no faces, just grasping limbs. I cross my legs and check the button on my collar; still closed. Could this room really be an office? Overly soft couches, neat little boxes of Kleenex, a plug-in kettle and modest selection of—I roll my eyes—loose-leaf teas. It feels more like a living room than a place of business. But of course, that’s probably the point. Dr. Simons is late. True, I was late myself. I sat outside in the parking lot, looked at the high brick building; fingered my necklace, its golden cross. But now I’m sitting here, on this pillowy yellow couch that wants to swallow me whole, and I’m upset. No—not upset—indignant. Aren’t these places supposed to make you feel at ease? Everything about the office is determined to repel me: uncomfortable seating and incomprehensible art, throwing accusations at me from across the room. And now, a doctor with too little respect to show up on time. God knows it was a challenge enough for me to make this appointment. But Connor insisted. I had to find the right words to Google, and nothing fit. Psychologist is vulgar, sterile, clinical--therapist seems to pathologize me--counsellor feels political, like a person with an agenda. I struggled through the stew of terms and sites, throwing random couplings of words at my tablet until I finally landed on her page: Dr. Stefania Simons, it said in a flowing script font, specializing in women’s individual therapy. Well I certainly didn’t want to talk to a man about this. I just hadn’t expected an office so vivid, so dramatic. I mean sure, I didn’t really expect much of anything—but therapy should be a greyer endeavour, should leave room for the patient to colour things in. The print of the red flower painting, which is the largest in the room, hangs above the opposite couch, right in my line of vision. It reminds me of Connor, of our wedding, of the blush-pink lilies I carried as I stepped gingerly down the aisle, unsteady in my turquoise pumps. Those damn pumps. Mom insisted I needed something blue, that I needed enough height to reach Connor’s towering frame. That night he pulled them off me himself, gentle, and offered to rub my swollen feet, but it only tickled; when he removed my dress I instinctively covered my breasts. It’s okay, he said then. It will get easier. It’s new for us. That was in May, under pinpricks of sparkling starlight that shimmered across the bed in the honeymoon suite; but now, in September, with the sweat and fire of summer behind us, it has been long enough. I touch the golden cross again. Connor gave it to me, two years before the wedding. He was the one who wanted to wait. He presented it to me in a little black box with a coat of arms on the front, shining like polished steel. I wear the necklace every day. I tried to want him, once. It was a productive afternoon—we worked together to clean out the car, dancing to pop music, shrieking as we sprayed each other with the hose. Afterward we went for a drive and found ourselves at a beach, the sea bathed in copper from the low-hanging sun. He laughed as I ran at the waves, jumping them, skipping over a tide that pulled everything forward. It all felt so easy. He looked softer in the fading light—mysterious, vulnerable. I tucked a finger into his beltloops and led him back to the car. When I kissed him, he tasted like salt, a warm, earthy flavour that reached to the back of my neck. I remembered this feeling, remembered Jacob Sawyer in the ninth grade, remembered the shivery sweetness of parting his lips with my own—but then. Dad. The shock in him, the furious revulsion. The memory settled in behind my ears as I stared out the passenger window. Connor’s fingers turned spiderlike, spinning a web on my knee. We got home, knocked the sand from our flip-flops, and I was glass—afraid to shatter. I tap my foot against the ground. The receptionist advised me when I got here that Dr. Simons would be late; she had called to apologize, on her way back from lunch. But that was twenty minutes ago, for goodness’ sake. My resolve is sinking into this couch. How do we even begin this conversation? Will I be expected to start it? Connor was the last one to bring it up—was always the one to bring it up. You just need to try, he keeps saying. Months ago, after the wedding, he wouldn’t say you—he would say I. I’m in no rush, I understand, I’ll be ready when you are. But then, somewhere along the way, it all became you. You aren’t trying enough. You should get over it. Here, do this. I pick up my purse. This is ridiculous—I’ve waited long enough. I cross to the other side of the room and put my hand on the doorknob. But before I turn it, the print of the big red flower catches my eye again. It looks different from this angle. It’s not all vibrant, I realize; a charcoal border traces the edge of the petals, the suggestion of a shadow. In the corner I see the name and date of the original painting. Red Canna, 1924, Georgia O’Keeffe. The year surprises me. The roaring twenties, such a quiet flower. The artist’s name means nothing, but I try to picture her anyway: flapper shoes, a short dark bob, a glittery, shapeless dress. She stands before an easel in the dusty light of a speakeasy. People watch, and they drink. In her hand is a brush. She uses slow, careful strokes, red layered on orange layered on incandescent white. I think I can smell the ocean. I think I can feel the tide, pooling around my ankles, poised to run. Nicole Chatelain Nicole Chatelain lives with her husband and two children in Ottawa, Ontario, where she teaches in the Professional Writing program at Algonquin College. She is finishing her undergraduate English degree with Athabasca University. She writes about sex, relationships, motherhood, and rare-disease parenting, and anything and everything else she feels like writing about. The Sign The edges toothed, the wooden board faces us bearing two white squares, angular states, maybe Tennessee, Nevada. They’re mute, the words worn away, and where eyes would be, two nail holes like pupils look out. Fall hasn’t yet browned the pasture beyond, where a mound is barely visible. Ohio is rife with earthworks the Mound Builders left, their giant snake effigy near Chillicothe visible from the air. The sign’s eyes say blind and nail-in-your-eye. Close up the wood grain is linear but wavers at the hairline, gradually slopes down and roils around an empty knot-hole where a mouth might open: Oh, it says, all ardor or surprise, worn and shorn of language’s complexity. The crooked, stiff vines behind, four or five, cut anywhichway, stick out, wiry hairs pulled, quirked: sign of madness or ravishment or martyrdom, since Oh can go so many ways. Maybe the pupils aren’t nailheads but holes invisible bullets riddled the sign with, as they did the first people––Shawnee, Chippewa, Miami–– small pox, the common cold. My eyes ache. I can’t look away. Mary B. Moore *“Invisible bullets” is scholar Stephen Greenblatt’s metaphor for the common cold’s effects on native Americans. Mary B. Moore’s poetry books include Dear If, (forthcoming, Orison Books); Flicker (Dogfish Head Prize, 2016); The Book Of Snow (Cleveland State UP, 1997). Chapbooks, both prize winners, are Amanda and the Man Soul (Emrys 2017) and Eating the Light (Sable Books 2016). Recent poems also appear in Poetry, Prairie Schooner, Birmingham Poetry Review, Gettysburg Review, ekphrastic.net, Nelle, Terrain, Georgia Review, 32 Poems, The Nasty Woman Poet anthology, and more. A retired professor, she lives in Huntington WV. Click on image above for the Starry Night responses, this time in an ebook form- free PDF.

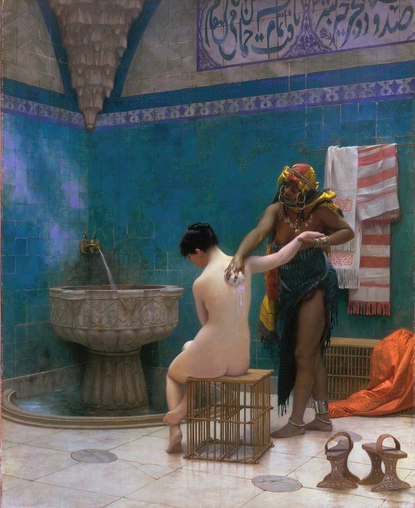

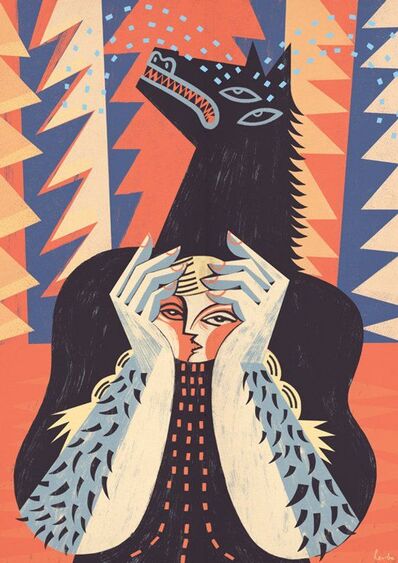

The Naked Storm after Angel No. 4, by Cui Xiuwem (China) 2006 She has to reproduce copies of herself because her baby won’t come full term, turning point in a naked storm where retreat and thunder are the same. Her iterations are calm, every tile, every eyelash, and none of her selves pierced by the roof splitting up, sea rise above the bridge. Many ways to wear white, she says, stomach punched. The government doesn’t allow processions, short skirts. What will you do with us all, no shoes, all the same, short-banged hair, red eyes from long nights with a tall musician and it’s only September a broken gate piercing with the wind how I, like a monster, just on the outside. Laurel Benjamin Laurel Benjamin has poetry forthcoming in Lily Poetry Review, Black Fox, Limit Experience, Word Poppy Press. Find her work in Turning a Train of Thought Upside Down: An Anthology of Women's Poetry, South Florida Poetry Journal, Trouvaille Review, The Ekphrastic Review (challenge finalist), California Quarterly, Midway Journal, MacQueens Quinterly, Wild Roof Journal, Tiny Seed, and more. She is an Oregon Poetry Association honourable mention, and is a Sunspot long lister. Affiliated with the Bay Area Women’s Poetry Salon and the Port Townsend Writers, she holds an MFA from Mills College and lives in the San Francisco Bay Area. Twitter handle: @lbencleo More at https://thebadgerpress.blogspot.com Ekphrasticon, by Ekaterina Dukas: a Review by Colin Pink Ekphrasticon, by Ekaterina Dukas (Europa Ediciones, 2021) (Amazon link) Europe: Europa Ediciones Ekphrasticon is a complete book of ekphrastic poems by the Bulgarian poet Ekaterina Dukas, written in English. Readers of The Ekphrastic Review might be familiar with her work, since several of the poems were first published in the magazine. In common with The Ekphrastic Review, each of the poems in the book is beautifully illustrated with a photograph of the art work in question so that the reader can pick up resonances from the interaction of image and text and see how the one sparks off the other. Dukas is a linguist by training and has a deep knowledge of how different languages function. In her poetry Dukas explores the musicality she finds in the English language in her own distinctive voice. The choice of subjects for the poems is very wide, ranging from the familiar masterpieces of western art such as Manet’s Olympia, Michelangelo’s Holy Family and Van Gogh Starry Night, to Palaeolithic cave art, ancient Thracian artefacts and poems inspired by music. But whatever the subject Dukas approaches it with a passionate engagement with the source material and explores the various resonances that it conjures up in the imagination. In Van Gogh’s Starry Night: His brush swirls in the thick of night a thief’s key in a prison lock to unchain the celestial sea. Blazing blue and liquid gold sea gods lunging headlong In Botticelli’s Primavera Dukas observes that: The three graces have arrived to adorn the soul of rebirth with Joy, Chastity and Beauty clasping hands with sacred grace along the bonding string of all beings, here wiring in their little palms. Handmade holiness. This image contrasts strongly with a much more earthy image of the same subject in a poem based on an ancient Thracian stone relief of the three graces. Here we have a much more authentically pagan vision: We bathed in the nymph’s spring, scented our skin with wild rose petals, draped our scarves over the shoulders and came to the forest for the dance… Here we get a sense of a pagan ritual actually taking place, instead of the balletic tone of Botticelli’s painting, and the urgency and important of this ritual dance, as the poem ends on the lines: You fare well along the weaving trail! We have to move heaven without budging the sky! The sky can also, of course, be the source of menace. In ‘Picasso’s Scream’ Dukas reflects on the enduring power and relevance of Picasso’s famous painting Guernica, with its ferocious condemnation of the violence of aerial warfare tearing innocence civilians limb from limb. At first the poet is reminded of Picasso personal violence in his relationships: “Nobody leaves Picasso” he shouted after his last lover, when she went away forever. Dukas contemplates the painting in the context of a group of school children, their reactions to the violent scene and their attempts to respond to it in their own drawings. Thus the message of violence is passed down through the generations.: …the pain so close, children are multiplying the loss. Some were trying to put on paper what they could see through tears and trembling fingers. One girl pencilled only a cross. Nobody leaves. Everyone remains with a piece of soul – a candle to Picasso’s Guernica of the world. Many of the poems in this book are profoundly meditative, reflecting vividly on our place in an uncertain universe and evoking a spiritual dimension that dwells behind the variety of imagery. This is a thought provoking book with a cornucopia of ekphrastic poetry. Colin Pink Colin Pink’s poems have appeared in a wide range of literary magazines and often in the The Ekphrastic Review. He has published several poetry collections: Acrobats of Sound, 2016 from Poetry Salzburg Press and The Ventriloquist Dummy’s Lament, 2019 from Against the Grain Press, and Typicity, from Dempsey and Windle, 2021. Titian’s Self-Portrait at the Prado Painted in his 70s, Titian’s self-portrait shows Him holding his gold and brown-flecked thin Paintbrush between the index and middle fingers Of his right hand. Turned facing to his right, He paints himself looking away from the viewer. He sets his black skull cap and coat against a dark Brown background. The white ruffle of his shirt And the thin gold double strands of his necklace Pick up the light brown of his right hand and paintbrush. His gold necklace is the chain of a Knight of a Golden Spur Granted by Charles V. The number 695 Is painted in red as if a ring on his right little finger. His eyes shine black; his beard, a whitish grey; his Skin, wrinkled with age. Rubens owned this unsigned Self-portrait of the artist. John Beall John Beall’s first book of poems, Self-Portraits, was published in 2019 by The Finishing Line Press. The poems, “Self-Portraits” and “November 22, 1963,” were awarded the Gwendolyn Brooks Poetry Prize in 2016 and 2017. His poems have appeared in The Henry James Review, Slant, MidAmerica, and Poems for Hemingway and Paris. His poem, “View of Mount Atalaya,” appeared in the summer 2021 issue of Slant. His poem, “Goya’s Self-Portrait at the Prado,” is due out next year in the collection: Song Up Out of Spain, to be published by Clemson University Press. Le Bain So hot my orange gown peels from my skin, so good to leave chattering birds, screeching monkeys, swirling red dust, only the soft trickle of the water fountain here amid the call to prayer, my soles cry out from the heat of the tiles, for my sandals. When I rub her pink skin with black soap she becomes black , like me. I rub it all over her, in every curve and crevice, circling, I take my time. She becomes like a doll to me, before I rinse her white again. My blue haven, this blue tomb. Her touch is sure, deft, sometimes she is rough. She pounds sea salt onto my skin, sometimes she rubs me red raw, sometimes I let her. One gasp from me she stops. He bought me at fourteen. Gold earrings, bangles, anklets hung on me, my skin burnished with cocoa butter, he checked my eyes, ears, mouth, that I was cut. Four sons I have given him, two nights in seven he comes to me, I am Umm Walad, the Mother of his sons. If I could just sit here, touching the hard wood of this cage, my toes burning, warm balm of her palms, sounds of her rubbing, breathing, scrubbing filling this chamber, before she drapes me in towels, dries me, dresses me, brings me to him. Some nights I am back in Ujiji, Mama is there and my brothers. I am ten, my face painted red and white, I am naked, wrist bound, waiting to be sold. I dream still, of the long walks,the beatings, the souk, the men. I am Umm Walad, I curse her Ger Duffy Ger Duffy lives in Co Waterford, Ireland. Her poetry has been published by Slow Dancer Press (UK), In the Gold of the Flesh Anthology (UK), Voxgalvia (Irl), The Waxed Lemon (Irl), Cathal Bui selected Anthology 2021, Drawn to the Light Press (Pushcart nominee 2021), Southword (Irl) and Local Wonders Anthology, Dedalus Press (Irl). Her poem “My Fathers’ Hands” won 2nd Prize at the Goldsmiths Poetry Competition 2021, her poem “She asks for Mercy” was highly recommended in the Westival International Poetry Competition 2020. In 2021 she received a mentorship in poetry from The Munster Literature Centre (Irl). When I married you, I didn't know you were a werewolf. On their wedding day, his side of the aisles were wolves and her side of the aisles were children. Her children. Many from a soldier who never returned from war. The children tried to pet the wolves and lost their arms. The children made weapons of defense. The mother did not notice. She was in love. That night, their first together, the werewolf said to never note his wolf, and if I leave at night, he said, do not follow. He swallowed the wine at once. She was lovedrunk. and when she woke in the middle of the moon, her children swooning dreamtops, limbless gleeful kids, stalks of whisk and feather, she ran to the woods in search of her new husband and her new husband had changed, rearranged his fur to show more fang, rearranged his tux for a luxury of mane, re-feathered, a car backfiring in exchange for a howl. How? she wondered. He was melting a gun. The handle was nearing the melt. Nearing drops of lava near the cavernous welt. It was heavy, the gun. She reached to hold it, to hold him, to beg him, and fell into the flame. He returned to disastered man with the tragedy of the magical moon. Sadly the gun was still there. Sadly the lava was not gone. His grief was a puddle on fire. An unmelted weapon. A hum. Benjamin Niespodziany Benjamin Niespodziany's writing has appeared in the Wigleaf Top 50, Fence, Salt Hill, The Indianapolis Review, Peach Mag, and elsewhere. He has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize, Best Microfiction, and Best of the Net. He works nights in a library in Chicago |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|