|

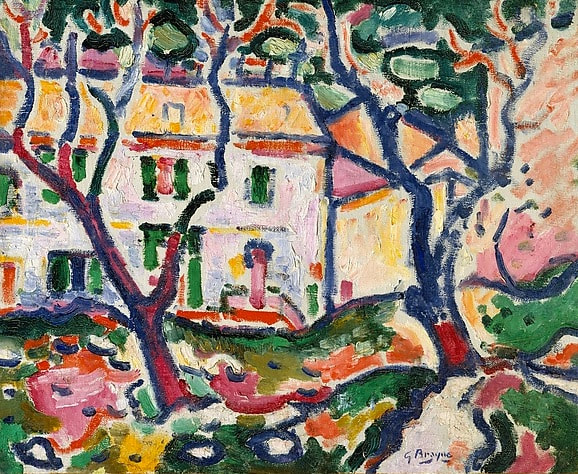

House Behind the Trees, 1906-07 I want to go home my friend’s mother says over and over, even though this is the house she’s lived in for fifty-some years. Alzheimer’s, dementia, same old story: they want to go home. I wish I could send them to this house behind the blue trees, with its solid flattened space, bright primaries outlined in bold strokes of cobalt. The rest of the colours run away with themselves, the spectrum as playground. Wouldn’t we want this, too, a return to childhood’s box of Crayolas, coloring the roof yellow if we felt like it, the sky, sea-green, with clouds swimming by like a school of fish. We could splash pink wherever we wanted, eat marshmallows for dinner, yell oley oley in free as the shadows twist and lengthen. Barbara Crooker This poem was first published in Barbara Crooker's book, Les Fauves (C&R Press, 2017). Barbara Crooker is the author of eight books of poetry; Les Fauves (C&R Press, 2017) is the most recent. Her work has appeared in many anthologies, including The Poetry of Presence and Nasty Women: An Unapologetic Anthology of Subversive Verse, and she has received a number of awards, including the WB Yeats Society of New York Award, the Thomas Merton Poetry of the Sacred Award, and three Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Creative Writing Fellowships. Her website is www.barbaracrooker.com

1 Comment

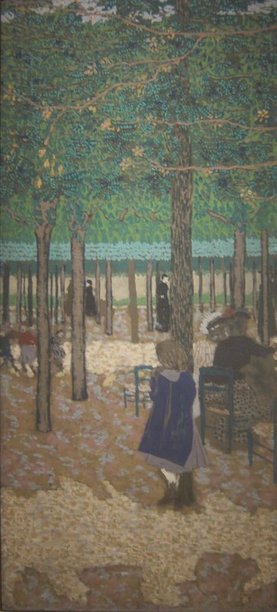

Under the Trees What do trees say when there is no danger and they feel content? This I would love to know. –Peter Wohlleben The girl knows. Leaning against one tree, half hidden, her foot crossed over the other, you might think she is bashful, hiding from the other children blurred in their play or that she spies on them, but she’s listening to the tree, her ear pressed against its bark. Everything in the park is dappled and dabbed, muted beneath mature trees so content and well-behaved they reach decoratively to one another, blooming, sharing a frothy pale blue fringe that rivers above the dark and upright governesses who walk faceless among them. In the dreamy, slow-time under the trees their roots murmur through fungal filigree, mycelium threads they use to converse, confide, deliver food to the dead, unwilling as elephants to abandon their fallen kin. Even giraffes know the wide-crowned acacias whisper to one another, send warnings through the moving air, so the giraffes browse faces to the wind. In forests mother trees recognize and and care for their kind. The girl is searching for a mother tree. Snug against this one she slows her mind, listening, uncertain what she listens for, listening all the same. Marion Starling Boyer Boyer has written three collections of poetry: The Clock of the Long Now Mayapple Press, 2009), Composing the Rain (Grayson Books, 2014), and Green (Finishing Line Press, 2003). Her poetry and essays have appeared in many journals, most recently The Tishman Review and Crab Orchard Press. She has moved this year to the Cleveland, Ohio area from Kalamazoo, Michigan. Arsonist’s Daughter

A bald cypress, the lone witness: “If it weren’t for Madeline, grown and gone, snorting moonlight’s paragon grooves, mending Dresses hemmed of midnight suns some Oslo summer, we wouldn’t have much to argue in favour,” sips rainwater in windturn. “She is not the daughter, it continues,” dipping its roots. “The father was a timid dolt, graceless and harmless. She is not the daughter; She is not sad laughter. Sparse remnants, dune memory. Resonance of touch.” The neighborhood aches off some mighty fine dead. “She is flames, flames on the side of my face… heaving, breathless… heaving breaths. She is the arsonist.” Past ash’s limit, breaks From the honeybunch tangerine trench to this taut limit limb, past as far as she can go, she does go. Heaving, breathless. Is limitless and conjuring. Andrew K. Peterson Andrew K. Peterson is the author of three poetry books, most recently Anonymous Bouquet (Spuyten Duyvil Press, 2015). His 2017 chapbook The Big Game is Every Night was sent to the White House alongside other chapbooks from Moria Books’ Locofo Chaps series as collective protest. Another chapbook, bonjour meriwether and the rabid maps (Fact-Simile, 2011) was exhibited as part of an installation of poets’ maps at the University of Arizona’s Poetry Center. He is a co-founder and editor of Summer Stock lit journal, and lives in Boston. The Masks

on ancestry-dot-com a collection of well-worn masks can be found it’s all in your genes they say on once-story-dot-com eventually the beach sculpture becomes a faceless dune nobody’s out there to connect the dots. Boris Kokotov Boris Kokotov was born in Moscow, Russia. Currently he lives in Baltimore. He is the author of several poetry collections. He also translated selected poems of German Romantics and contemporary American poets to Russian language. His work appeared in periodicals, most recently in Adelaide, The Bewildering Stories, Boston Poetry Magazine, Chiron Review, Constellations, The Lake, and others. Ophelia Among the Reeds

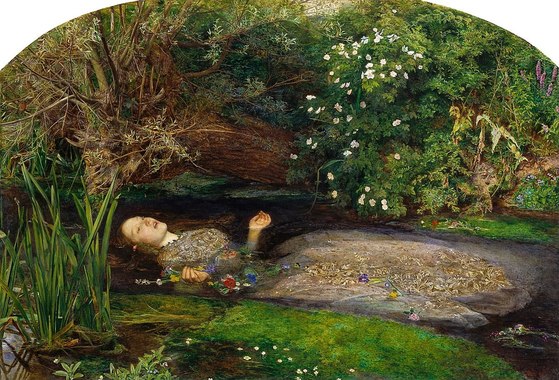

bedded in the stream carried by the current her palms upturned in seeming supplication her lips stopped in mid word her final question left unfinished like the flower chain that will never be a crown Lisa Stice Lisa Stice is a poet/mother/military spouse, the author of Permanent Change of Station (Middle West Press, 2018) and Uniform (Aldrich Press, 2016), and a Pushcart Prize nominee. While it is difficult to say where home is, she currently lives in North Carolina with her husband, daughter and dog. You can learn more about her and her publications at lisastice.wordpress.com and at facebook.com/LisaSticePoet. Bosch Fish

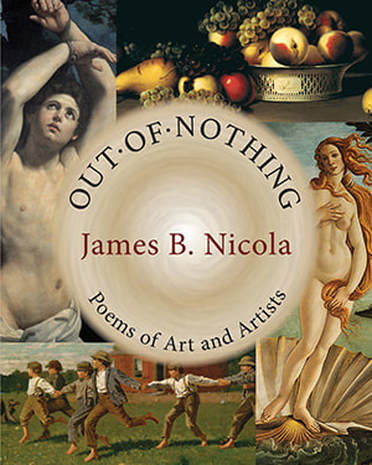

This is unnatural absurd. I don’t want wings it’s an abomination to fly like a bird. I don’t wish to be ridden like a work horse either. All I want is to swim swim in iridescent waters innocent of crimes fins and gills mine. But I am painted with this brush by Bosch who called fish liars who lies sleeping in his stony pious grave while I must always fly with sinners on my back no water only sky. Tricia Marcella Cimera Tricia Marcella Cimera will forever be an obsessed reader and lover of words. Look for her work in these diverse places: Buddhist Poetry Review, The Ekphrastic Review, Foliate Oak, Fox Adoption, Hedgerow, I Am Not A Silent Poet, Mad Swirl, Silver Birch Press, Stepping Stones, Yellow Chair Review, and elsewhere. She has a micro collection of water-themed poems called THE SEA AND A RIVER on the Origami Poems Project website. Tricia believes there’s no place like her own backyard and has traveled the world (including Graceland). She lives with her husband and family of animals in Illinois / in a town called St. Charles / by a river named Fox. The Ekphrastic Review Talks with James B. Nicola on Out of Nothing: Poems of Art and Artists5/25/2018 The Ekphrastic Review Talks with James B. Nicola on Out of Nothing: Poems of Art and Artists Tell us about how this book came into being. How did the idea come to you, and how did it evolve? What changed along the way? As the number of poems I had written (or was working on) grew, I began keeping them in separate files organized by theme. New York poems turned into my first collection, Manhattan Plaza; those about the theatre and performing arts, Stage to Page, my second collection; those about loss, longing, and the queasy feeling in the hollow of your gut that accompanies them, Wind in the Cave. The file that I had once called “On Art” has finally turned into a collection with illustrations: Out of Nothing. After Shanti Arts accepted it for publication, publisher Christine Brooks Cote and I began to discuss which images to use along with the poems. Only a few of the pieces are ekphrastic per se: Some poems called for several images; others, an image only indirectly, or tangentially, related to the text; still others, no image at all. Meanwhile, I revisited the flow of poems to fashion Out of Nothing as a single work of art in its own right, like a long poem or three-movement symphony, with several interwoven journeys: Chaos to Cosmos, ancient to post-post-modern, unborn to everlasting. You’ll notice, for example, that the prologue opens the book with the birth of Beauty, while the last word of the last poem is “stars.” How is writing ekphrastic poetry similar and/or different from writing from other sources of inspiration? Today, one can open a book or click on a website to see a piece of architecture or art, or its facsimile. So for my money, we need not spend so much time describing, which ekphrastic poetry did in classical Greece. Artwork for me has served as prompts to the poetic process, then, rather than simply as subject matter. Still, while I might like to go wherever inspiration, passion, and caprice take me, there is that other soul in the room—no, not the audience, who is always there-and-not-there (viz. my first book, Playing the Audience: The Practical Actor’s Guide to Live Performance). I mean the artist. In the same way you are never alone “When you read” (the title of one of the poems in Out of Nothing), so several souls are always involved when you experience art. Ekphrastic poetry—what with reader, artist, and poet in tow—cannot help but be communal. Has writing poetry from paintings changed the way you look at and respond to art? When I go to a museum or gallery, there’s now a strange, inscrutable whisper deep in my gut telling me that my silent reactions do not have to stay silent. The humility of subjecting oneself to something greater, ironically, can turn into an arrogant expression of that very act of “subjection!” What’s more, once I’ve written a poem about a work of art, it is nearly impossible to see the artwork again without recalling that poem. The first time cannot be repeated. You write about a wide variety of styles of art. Did you always have a wide appreciation for art, or did writing ekphrastic poetry broaden your horizons? I still remember as a little kid the first time I saw the Worcester Art Museum’s El Greco, with its eerie lighting and other-worldliness. When I was in third grade, a fellow student (a recent transplant from New York City, no less, whose mom had met mine through the museum guild) painted a very funny series of overlapping shapes in various colours—squares, triangles, circles, and so forth—while the rest of us were painting trees, hills, beaches, houses and whatnot. That was the day I first heard the term “pop art” —from that fellow student. So on my next trip to the museum, there was a lot to explore. My mom even took my brothers and me there for Saturday art lessons for a couple years. So I am not sure if writing ekphrastic poetry “broadened my horizons” as such, but the fact that I loved and appreciated art on my own long before taking an academic course in it meant that I automatically knew to experience the thing personally first, before letting anyone tell me about genre or style or “ism.” To this day, at an exhibit, I will read a curator’s caption only after first engaging with the work of art directly. This independent, intrepid attitude has helped me to see what is there rather than what someone says I am seeing, and kept me open to new experiences, exotic cultures, and innovative visions. What are some of your favourite poems in the book? Tell us why, or what they mean to you, or how they happened. Poems are so like progeny, so asking for favourites is like asking a parent to pick a favourite child—I simply can’t do it. But I can mention some poems that have been particularly satisfying to perform lately. I often start a set with “Where does art/start?” which is at the beginning of the book. I performed it as the NY Poetry Festival back in 2016, by the way, and a young poet wrote a pastiche of it which got published in a British Poetry Journal on-line, citing Out of Nothing as its source—long before my poem was published elsewhere! As a closer of a set, it’s fun to perform “Tower,” the last poem in the book, with its concise cosmic twist. A couple of the narrative poems have been quite fun for audiences: “Water Lilies,” which is not just about Monet’s painting glazed on a coffee mug, but ultimately about the beginning of everything; and “Yesterday’s Rains,” where the point of a certain arts & crafts festival sort of sneaks up on the listener, as does the point of the poem—and of art. * Out of Nothing: Poems of Art and Artists, James B. Nicola, Shanti Arts, May 2018 Click here to learn more about or purchase Out of Nothing by James B. Nicola at Shanti Arts. Visit James B. Nicola's website, or order an autographed copy, by clicking here. Raven at the Crossing

Do you seek a pattern in all this whiteness, asks the woman dressed as a raven. Or is she a raven, cloaking a woman in feathers and wool? You’ve tramped through new-fallen snow to this edge where land dissolves into not-frozen water, where fog is indistinguishable from water, sky inseparable from fog. Woman-Raven, Raven-Woman—her blackness is a bridge between these white strata: snow-covered scrub, water, fog, sky. Her curtsey drags the hem of her cloak in the drifts, bows her long cardboard beak toward the water. If this is a gate, she is its keeper. Where her corvid mask points, you see a distant line of grey figures. Snow-covered trees, most likely. Or ghosts. Another land at another water’s edge. Would you go, if a boat waited? There is no boat. There is only a raven dressed as a woman in a raven costume. A bare branch overhead hints at an invisible forest. Red and white beads hold feathers to her cloak. The beads rattle like icicles falling into each other. Red is the world’s only colour, the only sound in the silence. Hannah Silverstein Hannah Silverstein lives in Vermont. Her writing has appeared in Si Señor, The New Guard, and SWWIM Every Day. Margins

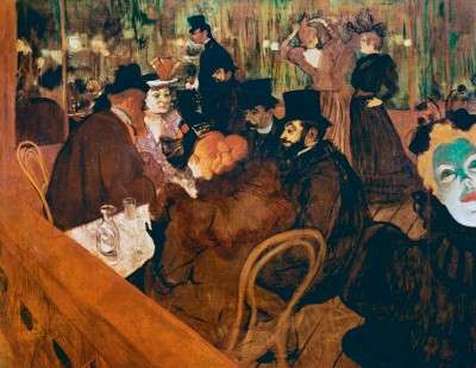

There will be time, there will be time To prepare a face to meet the faces that you meet; There will be time to murder and create, And time for all the works and days of hands That lift and drop a question on your plate; Time for you and time for me, And time yet for a hundred indecisions, And for a hundred visions and revisions, Before the taking of a toast and tea. --T.S. Eliott With the precision of a surgeon, he spliced your canvas-- lacerated the fibres and dismembered your vision, assured that his recension would temper provocations, the suggestion of swinging calves, shaking rumps and switching skirts, stirring the yearning of outcasts who gathered in bar chairs on balconies and poised tenuously on stairs-- They emptied their cups to numb the absence. You sat among them, filled your glass to the brim and above the brim another round that burned down until the green fairy's swirled apparitions, acidic and swift, appeared in darkened corners, unnoticed like loose strings in the fringes of bar-rooms You disappeared with your musings, in your muses, you painted yourself into the foreground, the background, the periphery where you belonged. In shadows, you conjured her, with skin acerbic, her caustic gaze, Her face--fantastic--detaches from her frame and swallows yours whole. There’s a fissure in the skin of the canvas. Set like a limb reattached, She leans into the break to gaze--a spurned lover cast aside to survive only in brush-strokes of alleyways--drown in oceans of arsenic. She reminds us to listen for the ghosts in shavings of erasers, to see yet what lingers in the margins-- their hauntings in wasted papers. Erin Holtz Poet's note: "This past spring, I took my two little girls to The Art Institute in Chicago. As usual, we stopped to see Toulouse-Lautrec's At the Moulin Rouge. I crouched down to talk with my youngest about the 'green lady' in the painting, and it was the first time I saw a suture in the canvas--it was cut by an art dealer who believed the inclusion of the 'green lady,' May Milton, decreased the painting's value. It was later reattached. (It astonishes me how we can see art so differently from various angles and points of view.) From that visit, I knew I wanted to tie together the idea of creation and revision in an ekphrastic poem, a marriage of TS Eliot's relationship with Ezra Pound and posthumous splicing of Toulouse-Lautrec's painting by an art dealer." Erin Holtz teaches English and Creative Writing in the Chicagoland suburbs and writes poetry late at night. She has been published in Mothers Always Write and in Lament for the Dead. Exhale “I think everything in this room is about residential schools,” Alice says. I turn and take in the four black walls And sink a little into the ground. Oh. Exhale. When we reach the painting on the back wall My eyes go straight to the middle Where a woman Is being torn away from her child. The mother’s expression-- Defiant, Desperate, Terrified. The child’s-- Gone. “I am having a hard time facing this one,” I say. Exhale. Feeling a compression stretch Across my chest I think I have nothing left To breathe out But then, I look up. Empty Baby carriers And Missing ones Outlined in chalk. Clarissa Mae de Leon Clarissa Mae de Leon is a PhD student at the Queen’s University Faculty of Education where she researches curriculum theory and multiliteracies. She lives in Kingston, Canada with her greyhound, Emilio. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|