|

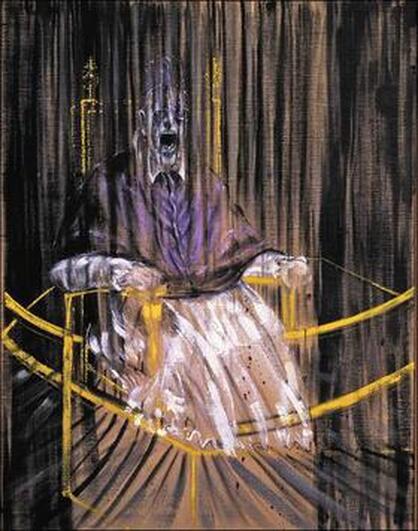

Francis Bacon, Study After Velásquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X That papal scream, mute, horror-shadowed. Prisoner of infallible goodness. The unheard urge to desecration, foulness. Innocence? Hardly, rather the howl of flesh. Go back to Velásquez, to his Pope’s giver of writ. Knowing of office, ceremony, decree. Document to hand, trim of beard, alert. Due etiquette of power, Vatican red and white. Compare Bacon, the iconoclast’s purple. Caged, fist-curled, venting mouth. Hidden eyes, exposed teeth, the ghost of himself. A Dorian, ecclesiastical Hyde, the Opera’s phantom. And those vertical paint-lines, tunneled bars. They hold their pontiff inside his cylinder. Cowl, collar, mitre, white robe, the parodies of command. Peter’s heir a shouting inmate, a hidden masquerader. Look to Bacon’s other popes, other heads. Their Eisenstein scream, their Picasso deliquescence. And Innocent’s utterance, to be seen as heard. Convex, dysmorphic, the painting eye’s distortion. A. Robert Lee This poem first appeared in Imaginarium: Sightings, Galleries, Sightlines, 2Leaf Press, 2013. A. Robert Lee was Professor in the English department at Nihon University Tokyo, 1997-2011. British-born, he previously taught at the University of Kent, UK. His creative work includes Japan Textures: Sight and Word, with Mark Gresham (2007), Tokyo Commute: Japanese Customs and Way of Life Viewed from the Odakyu Line (2011), and the collections Ars Geographica: Maps and Compasses (2012), Portrait and Landscape: Further Geographies (2013), Imaginarium: Sightings, Galleries, Sightlines (2013), Off Course: Roundabouts and Deviations (2016), Passsword: A Book of Locks and Keys (2016), Written Eye: Visuals/Verse (2017), Alunizaje/Lunar Landings, with Blas Miras (2019), Writer Directory: A Book of Encounters (2019) and Suspicious Circumstances. What? (2020). Among his academic publications are Multicultural American Literature: Comparative Black, Native, Latino/a and Asian American Fictions (2003), which won the American Book Award in 2004, Modern American Counter Writing: Beats Outriders, Ethnics (2010) and The Beats: Authorships, Legacies (2019). Currently he lives in Murcia, Spain.

0 Comments

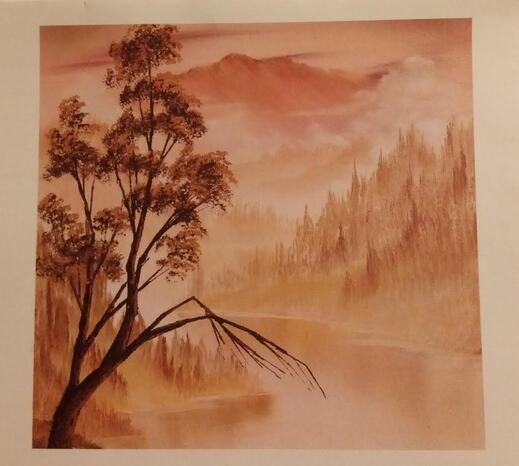

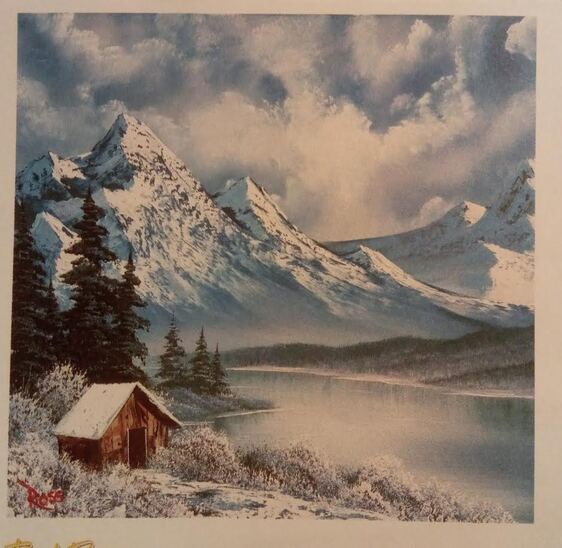

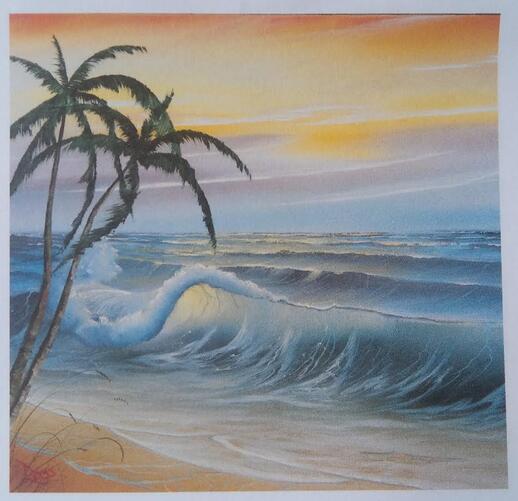

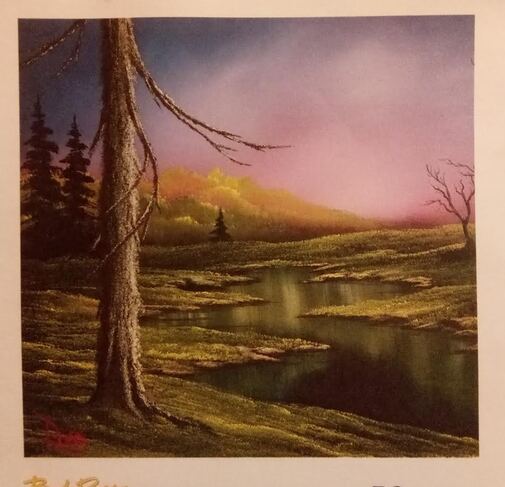

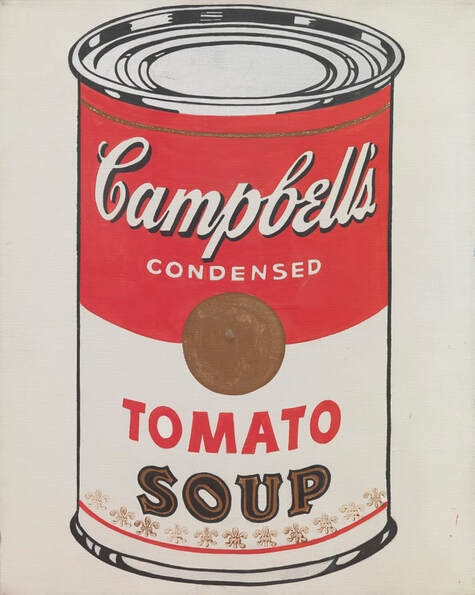

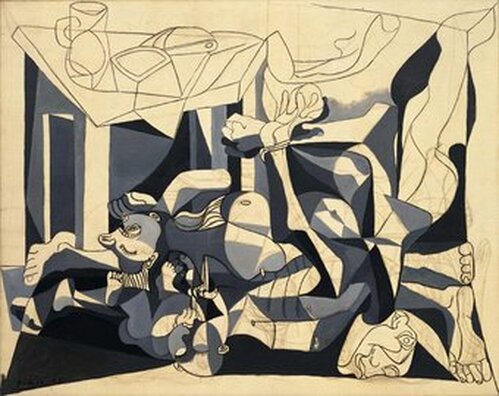

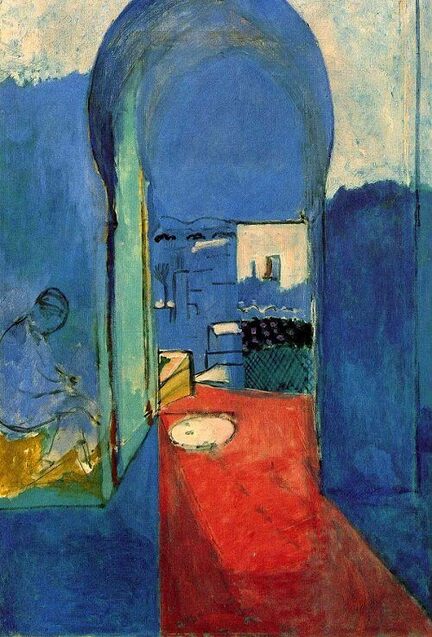

Far Away Straight stem spine reaches up the dark mother watches over the lake her high leaves shower in majestic light as black twigs sway above the serene surface. All over the hillscape behind golden needles spike through the mist. Far behind the eternal rock pushes aside the clouds and the early sun paints it in warm orange as it glances satisfied over the peaceful scene. Leaning Peaks With serene indifference the white peaks lean against a heap of restless clouds sprinkles of green are brushed over the smaller ridges in front. A few needled giants spike proudly above the snow-coated bushes nearby on the shore of the frozen lake in the centre its surface a mirror that calmly reflects softened shades of blue and grey putting the troubled sky to rest. Seaside Curious stems sway over the sand underneath the wooden twins that caress the breeze with sturdy palm leaves. The golden light above recedes into copper breathing glow onto the waters of an endless wavescape flowing from the horizon pulsing towards the land the shimmering waves burst rhythmically into white greeting the twins with joy. Nightfall Distant violet announces dusk final glimmers of orange fade from the summer green that covers remote hills. Lonely pines stand strong mossy meadow carpeting the scene overlooked by the old father settled near the pond thick bark white wisdom overseeing the water blending with the dark green of the meadow as the distant violet fades. Martin Breul Martin Breul is a graduate of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Glasgow, Scotland. He spent one year studying in Toronto, Canada, where he began to write fiction and poetry. Ever since, he is determined to spend time in coffee shops surrounded with books and paper, pretending to be a writer, until his fellow caffeine-addicts believe that he is one. His poetry appeared previously in Half A Grapefruit Magazine and his academic work has been published in [X]position. He is currently pursuing a MA at McGill University. Join us for biweekly ekphrastic writing challenges. See why so many writers are hooked on ekphrastic! We feature some of the most accomplished, influential poets writing today, and we also welcome emerging or first time writers and those who simply want to experience art in a deeper way or try something creative. The prompt this time is Tomato Soup, by Andy Warhol. Deadline is November 13, 2020. We encourage submissions of flash fiction or creative nonfiction! Poetry is always welcome- we love poetry! We are simply hoping to attract more fiction writers and fiction readers. Please keep submissions under 1000 words. The Rules 1. Use this visual art prompt as a springboard for your writing. It can be a poem or short prose (fiction or nonfiction.) You can research the artwork or artist and use your discoveries to fuel your writing, or you can let the image alone provoke your imagination. 2. Write as many poems and stories as you like. Send only your best works or final draft, not everything you wrote down. (Please note, experimental formats are difficult to publish online. We will consider them but they present technical difficulties with web software that may not be easily resolved.) Please copy and paste your submission into the body of the email, even if you include an attachment such as Word or PDF. 3. Have fun. 4. USE THIS EMAIL ONLY. Send your work to [email protected]. Challenge submissions sent to the other inboxes will most likely be lost as those are read in chronological order of receipt, weeks or longer behind, and are not seen at all by guest editors. They will be discarded. Sorry. 5.Include WARHOL WRITING CHALLENGE in the subject line. 6. Include your name and a brief bio. If you do not include your bio, it will not be included with your work, if accepted. Even if you have already written for The Ekphrastic Review or submitted other works and your bio is "on file" you must include it in your challenge submission. Do not send it after acceptance or later; it will not be added to your poem. Guest editors may not be familiar with your bio or have access to archives. We are sorry about these technicalities, but have found that following up, requesting, adding, and changing later takes too much time and is very confusing. 7. Late submissions will be discarded. Sorry. 8. Deadline is midnight, November 13, 2020. 9. Please do not send revisions, corrections, or changes to your poetry or your biography after the fact. If it's not ready yet, hang on to it until it is. 10. Selected submissions will be published together, with the prompt, one week after the deadline. 11. Rinse and repeat with upcoming ekphrastic writing challenges! 12. Please share this prompt with your writing groups, Facebook groups, social media circles, and anywhere else you can. The simple act of sharing brings readers to The Ekphrastic Review, and that is the best way to support the poets and writers on our pages! The Charnel House Oliver didn’t think about art, not that he had anything against it. It was just something he had never paid attention to while growing up. His mother painted watercolours, but he never considered her paintings art. Painting was simply what she did in her spare time. It was a hobby. Once when he was seven his aunt took him to see a Van Gogh exhibit. She told him that Van Gogh had a mental illness that accentuated his creativity, but she didn’t explain why anyone would be interested in seeing the paintings of a mentally ill person. It was the same with Picasso. Everyone said he was great, but no one explained why. When Emily, a friend from work, asked if he wanted to come with her to see a Picasso exhibit, he wasn’t sure what to say. Two weeks before, he and Emily had gone to lunch at a café in the Mission District. He found her attractive, interesting. She talked about art, music, and nature, plus she was funny, and seemingly passionate about everything. When she asked about going to the exhibit, he admitted he knew nothing about art. But the more she talked about it, the more he wondered if he could learn what made Picasso great. But more importantly, he wanted to spend time with her. The exhibit was called Picasso and the War Years, a collection of paintings produced before and during the Second World War. As the two of them walked from one room to another in the museum, Oliver found the paintings confusing and disturbing. He saw a grotesque dancer with distorted limbs holding a tambourine. He saw squiggly lines that suggested a bird from one perspective and a three-eyed woman from another. Another painting showed a bizarre looking female with an ear where her nose should be and a nose stuck to the side of her face. And skulls. There were human skulls, sheep skulls, and cow skulls. What was the point? he wondered. Oliver glossed over the exhibit brochure and read that Picasso was the greatest artist of the 20th century. He assumed the museum people must know something, but nothing in the exhibit looked remotely familiar. There were no trees or mountains or cows in a field or portraits of normal looking people. The paintings seemed to have come from the mind of a madman. No other explanation made sense. He was clearly out of his element and began to think he’d made a mistake. Emily marveled at paintings he couldn’t possibly comprehend. Clearly it had been a bad idea to go with her to a museum. A woman like her would never be interested in someone like him. Oliver was anxious to get through the exhibit as quickly as possible. Emily wanted to take her time and study each piece. They agreed to meet later in the bookstore. Oliver walked quickly through the next room glancing at portraits of strange, hideous figures. Dark, unexpected colors on contorted faces, many of whom appeared to be weeping. One figure was painted green. Several were little more than unorganized scribbles. One showed a nun in black with an exposed breast and her arms raised. Another depicted a screaming woman holding a dead child. The only concession Oliver could make was that the subjects and colors were bold. He stepped into a room with a full-sized reproduction of Picasso’s most famous painting. The sweep of Guernica captured him. He stopped to take it in. A horse in agony. Dead and dying people. A ghostly figure coming into the house holding a lamp. A bull with demonic eyes. Oliver didn’t know what the painting represented other than a depiction of war. He took a deep breath and moved to the last room of the exhibit. This room was dominated by a single painting more disturbing than the others. He stepped close to read the label – The Charnel House – then stepped back. It was gray and black with exposed, raw, yellowed canvas. The painting appeared like an open window, as though he was looking through onto a horrific pyramid of broken bodies, including that of a small child. They reminded him of overripe, rotting fruit, discarded refuse. In the lower part of the painting the light was dying, falling to angular pools among the bodies, into blackness at the edges. The drawn and painted figures were stripped, tortured, and bound. He noticed erasures of earlier, forgotten deaths. These figures, he realized, were the victims of every war, buried under a table of undeniable abundance with a pitcher, probably of wine, and a loaf of bread. The label stated that Picasso had intentionally left the painting unfinished, since the brutality and senselessness of war hadn’t ended when Picasso stepped away from it. Oliver found that he couldn’t take his eyes from it, especially the large unpainted areas of the canvas. Perhaps because there was less brutality in the empty spaces. Perhaps because he felt safe resting his eyes there. Perhaps because they reminded him of the same soft yellow of the mud house outside of Kandahar, the one he had entered minutes ahead of his team members. Oliver walked slowly through a courtyard surrounded by mud walls. A dawn rocket attack had destroyed most of the village. It was believed that the houses had been abandoned and insurgents were using them to store weapons. This house was one of the few still standing, although its wooden door had been blown in. As he approached, he heard the sound of someone crying. Oliver knew only a few phrases in Pashto. He called out tas-leem saa, the phrase for “surrender.” No one answered. He said it again. When there was no response, he called out in English, “come out.” Still nothing. He stepped to one side of the opening and shined a light into the room. The crying sounded like that of a child. Slowly, he stepped through the door and swung the barrel of his rifle across the room. He stopped at the sight of a small child, a girl, sitting on the floor next to a dead woman, probably the child’s mother. The woman was lying contorted on the floor in a pool of drying blood. As the other team members entered, Oliver turned and ran out of the house. He turned away from the painting and closed his eyes, but the crying didn’t stop. He found it difficult to breathe. He looked behind him, saw a long wooden bench, and sat down. Then he glanced around the room. There were no children in the room, just an elderly woman sitting on the far end of the bench. He turned toward her. “Do you hear someone crying?” The woman looked at him, shook her head, and turned back to the painting. Oliver didn’t understand what was happening. The sound was so clear. Was it coming from the painting? He looked again at it and wondered if the canvas, paint, and imagery had entered his head. He felt a flash of anger at Picasso, as if the artist had used his brush as a weapon and Oliver himself had become the target. The crying seemed to grow louder. “Oliver?” He jumped at hearing his name. It was Emily. He stood quickly and smiled an embarrassed smile. “Are you alright?” she asked. “Fine, fine,” he said, rushing his words. “It’s... a remarkable exhibit. I’ll wait for you outside if that’s alright.” “Sure,” she said, puzzled by his abrupt behavior. She watched as he quickly left the room. Then she turned and looked at the painting. She wondered why Picasso had left it unfinished. Jim Woessner Jim Woessner is a visual artist and writer living on the water in Sausalito, California. He has an MFA from Bennington College and has had poetry and prose published in numerous online and print magazines, including the Blue Collar Review, California Quarterly, and Close to the Bone. Additionally, two of his plays have been produced in community theatre. Ghazal as a Translated Conversation Between Two Women at the Side of the Kasbah (“As-salamu alaykum, sister.” “Wa alaykum as-salam.”) They both walk along the outer wall of the citadel, resting on the side, Streets blue-heavy / mirror sky / sun rose in the east this morning, now shining on the north side. One woman has blue shoes to match. She looks at the other: “How are you in this soft midday?” “Alhamdulillah, and you?” “Alhamdulillah. My niece was born yesterday, in the countryside.” “Mashallah, sister’s daughter?” She nods. “Will you be visiting her?” “Soon. There is still much to do here. Sister has asked me to give her daughter a name, and pluck it from the coastside where our mother found hers.” “Has she given you any options?” “Three handfuls; each one not enough for her daughter but too perfect to let fall away. It is too much to decide.” “My mother did not name me after I was born. You only name the daughter if you want to see her again. But I knew she had something to call me by, while the world turned nightside. That girl is dead now. She could’ve been called Rabia or Jasma, and maybe she would’ve loved the springtime a little more, but it doesn’t matter. My mother only whispered it to her bedside.” The two women look down and let the sun move further west / still above them for a while longer / silent / setting. “But what is your name, sister?” “Iqra. Iqra Syed.” “Cleaved from the spine of a book.” Iqra smiles. The woman with the blue shoes looks up at her as they enter the kasbah / mirror sky / mirror smile / the land is less steep on this hillside. In time, they will find new words to call each other by. For now, Iqra’s name will be plucked / placed on the newborn’s bedside. Munira Tabassum Ahmed Munira Tabassum Ahmed is a 15 year old Bangladeshi-Australian writer and creative. Her work has been recognized by the Australian Poetry Slam, Sydney Writers' Festival, Express Media, UN Youth, AELA and Australia Remade. She has received national honours and international publication for her poetry, which is published or forthcoming in Voiceworks, The Lifted Brow, the Sonora Review and elsewhere. To everyone who has purchased The Ekphrastic World big book of prompts, thank you so much for supporting this tremendous journal.

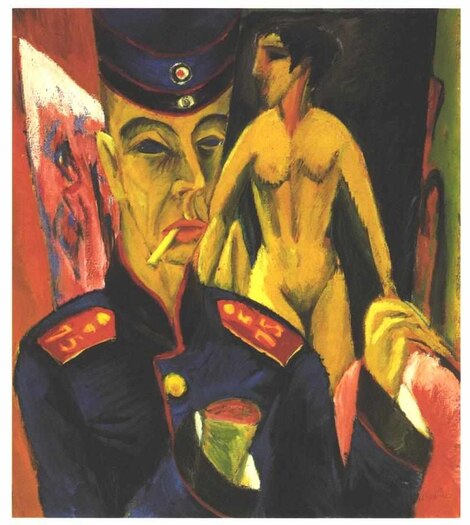

Just a reminder that your poetry and prose submissions from the selection of prompts are due on November 1. I am very excited about reading everyone's work and putting together an amazing anthology! Thanks so much! Fatherland "...the goal of my work has always been to dissolve myself completely into the sensations of the surroundings…" Ernst Ludwig Kirchner I. I was labeled Degenerate because of how my palette changed from lush blue-grays and velvet greens and plush maroons before the war, to flesh pink, blood red, shit brown, piss yellow, and death black after I came back from months in the trenches. The war took more than my colours. II. Every face I fathered after the war mirrored my face: ghastly, haunted, ghostly. Jaundiced eyes stared accusingly into my eyes as I painted one suicide, then another, and another. I would never be satisfied until my face became Death’s face. III. Safely back home, I hacked my own hand from the thin branch of my arm. Exactly how many hands, legs, and heads did I see needlessly liberated from the torsos of my fellow brothers in arms? I knew how sharp my brush could be. The least I could do was give them some part of me. But in the end I owed the dead more than just my hand. Kip Knott Kip Knott’s writing and photography have recently appeared or are forthcoming in Cathexis Northwest Press, La Piccioletta Barca, perhappened, Third Wednesday, and Versification. His debut full-length collection of poetry--Tragedy, Ecstasy, Doom, and so on—is available from Kelsay Books. More of his work may be accessed at kipknott.com. First View- Chicago Lakes Sleet needles past my fastened collar as we rise into the house of rain. Mr. Byers of the Denver News has horsed us up this flyspeck path with avowals of Alpine views but now is silent. I think he has missed the spur trail. My blood is gelid, fingers numb beyond recovery. Clouds tickle and drip and when we crest this timbered ridge I must ask that—Oh! Sublime cirque! The Alps surpassed again! Stay the mules—I must—I need my paints, stool. Fifteen minutes, please you; see how the near lake mirrors the breaking storm with light fine as milkweed fluff, that one pearled peak soft as the edge of heaven! Kenneth Chamlee Kenneth Chamlee is Emeritus Professor of English at Brevard College in North Carolina. His poems have appeared in The North Carolina Literary Review, Cold Mountain Review, Ekphrasis, and many others. He won ByLine Magazine's National Poetry Chapbook Competition (Absolute Faith, 1999), and the Longleaf Press Poetry Chapbook Competition (Logic of the Lost, 2001). His poems have appeared in six editions of Kakalak: An Anthology of Carolina Poets. He is currently working on a poetic biography of painter Albert Bierstadt. Learn more at www.kennethchamlee.com. Theory of Relativity There is a flurry of wind as the world becomes a metaphor. Are you listening? The way the sky slopes in, waiting for its breaking point. Chalk leather seat, static fuel blooming in the valley. All that time, I was imagining the fracturing feathering of a heart detached from gravity. I knew back then—how Earth’s acerbic thrum rocks an engine; how weathered glass arches against my fingertips like flame in a tornado. Here’s a secret: we don’t know silence until it’s injected into the void, choked and gasping. It’s lonely here, like my room, gaping and stickered with stars. How ten thousand miles an hour feels like nothing. How thirty years feels like nothing. Life flashes before my eyes in the vortex between dreams and reality. Pressure plasters my chest like a slab. This rocket punctures the clouds like a bullet, salient enough to leave an exit wound. It’s a precarious peace: synchronously racing and loitering. A precarious peace: this barren home. Emma Miao Emma Miao is a Chinese-Canadian poet from Vancouver, BC. Her poems appear in Cosmonauts Avenue, Glass: A Journal of Poetry, The Emerson Review, Rising Phoenix Review, and Up the Staircase Quarterly, among others. The winner of the F(r)iction Poetry Contest 2020, Emma is a Commended Foyle Young Poet 2019, a COUNTERCLOCK Arts Collective Fellow, and an alumna of the Iowa Young Writers' Studio. Her poetry and piano album, Oscillation, is forthcoming this winter. Find her at emmamiao.weebly.com. Regarding the Portrait of Antonietta Gonzalez The little girl, since she must pose, looks straight at her beholder—first the woman who dares paint, then anyone who might equate a syndrome with a character. A slew of such wrong-headed theories ran throughout each court she came to—by another’s power-- to be gawked at, examined, talked about as if a beast. No longer would she cower before such brutes. Instead she holds a page-- unfolded—telling how her father had been found, shown, shared; herself as well. The age was mad to see a hairy creature clad in rich brocade, the offspring of a wild man (mother not worth mentioning). Some child! Jane Blanchard This sonnet first appeared in The French Literary Review. This sonnet, first published in The French Literary Review, is the work of Jane Blanchard, who lives and writes in Georgia (USA). Jane’s fourth collection with Kelsay Books is In or Out of Season (2020). |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|