|

The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Deijman He peels and peels and unfurls your scalp-skin like an orchid does for a lovestruck bee, except, there is no love here pink watery brain, almost spongey; he holds a thin blade that slices the light and slicks it through your entirety - the part of you that named itself a man watches on, bowl in hand For what? what’s the bowl for? he doesn’t answer just watches - your face, shadowed dived into your dimples, hands positioned like your well rested he points to your medulla and says: see, the soul he points to your hippocampus and says: see, the hunger which is almost true but maybe, this was all for vain who cares what you remembered? the silver-dusted watch you left in Vermont while you undressed to learn love the Bible you got as a kid to learn God, from which you tore out all the pages about hell - what did you need with hell anyway? what was waiting for you at the end was sure to be filled with pearl clusters and grapes filed through your mouth - he pulls your limbs back macabre museum exhibit draws close your scalp and tosses you back into the storage to be pulled out again like a root vegetable to be displayed again later all around us, white light braids into a screen, this, is maybe, heaven, and God watches on, learning anatomy Janiru Liyanage Janiru is a fourteen year old Sri-Lankan/Australian student and poet who lives in Sydney. Aside from poetry, he loves maths and has received numerous awards in both national and international math competitions/olympiads. He is the 2019 junior winner of the national Dorothea Mackellar Poetry Awards and is also a prolific participant and winner of poetry slams. His work is forthcoming or appears in [PANK], The Journal Of Compressed Creative Arts & elsewhere. Having just begun his personal poetic journey, Janiru is eager to find his own voice in his work.

1 Comment

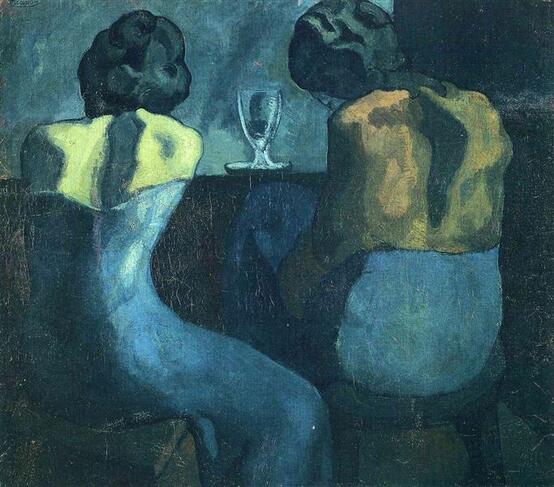

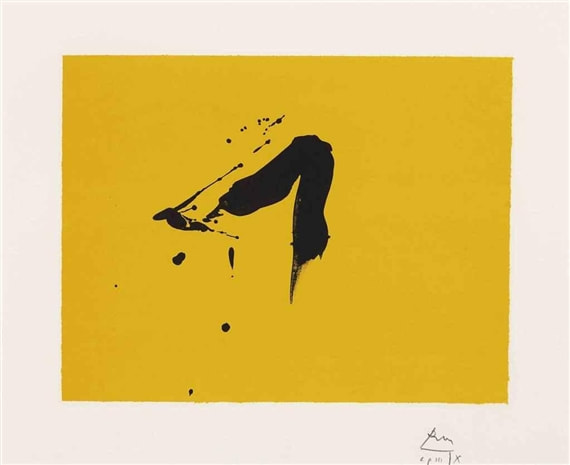

Rothko On A Motherless Night The hollow womb of the universe Pitch black throw back The bitumen graveyard starless Where? Why? Who am I? Help me The tin can witch holds her whip flogging, lashing, whisking the sodium aluminum silicate until the tone is short and buttery Jump, stark naked, through the stone circle Where the wind meets the see the noose ends, free Will it be me, born again? Help me Blanka Pesja Blanka Pesja is a poet and and a painter who designs art education. She teaches pop musicians at the Conservatoire about art, language and image. She produces experimental albums with her DarkEnsemble and promotes a feminist support group of young talented women. She lives north of Amsterdam (The Netherlands) with a cat that seems to hate her. To Dissolve I would sit at a blue bar in a blue century an empty glass and a reflection a tired tilt of the head - blue for blue’s sake, I would sit there in Spanish Celsius, stuck in a shadow while the woman at my side lets the naked narrow of her back unfold mysteries leans like an invertebrate into the blue, into this lonely, stoic blue we’d sink until all we are is a goddamn hue from 1902, dissolved of the duties of this grayscale reality Tristan Franz Tristan is a writer from Brooklyn, NY. His poetry is driven by the power of place and the human need to explore. He is also inspired by full moons, new languages, human kindness and tacos. You can find his work in a variety of online literary magazines. Learning to Fathom They slide past without ever seeing, cackling about the linoleum in their grandmother’s kitchen, their son’s recent finger-painting. I stand and wait for whitecaps to furrow your moss-sea surface, for any disturbance in the colour field. Light transforms two hours: Viridian, artichoke, emerald, forest, sage, juniper, lime, crocodile. You’ve returned from Giverny and gifted us with this green table— much better than any blank slate—where we can inscribe our lives. Thank you, Ellsworth, for losing your hard edge, for inviting us to float on this generous verdant plain, to submerge, to immerse ourselves in prairies of wild celery and meadows of fine eelgrass, to undulate with your undertow, to somersault with your waves. I can plumb your avocado shallows, sound your seaweed depths. I’ve learned how to swim. I’m stretched, flexed, and ready to dive. Jay Jacoby Jay Jacoby: "I am a happily retired English professor having taught for most of my career at the University of North Carolina at Charlotte. I now live in the Western North Carolina mountains and I'm able to focus my energies on creative writing. My writing has appeared in such journals as Asheville Poetry Review, Cold Mountain Review, Meat for Tea, and The Jewish Literary Journal."

Slough a leg though he called it a sun <<sol>> as though printed Henry Miller and bathed (see) by Huxley’s title but the leg splashes skin off within this to say what of [flaying] you can call it a death or melancholia ‘how can it be that I abhor her yet am her,’ Julia, and is that your shadow, not skin, and it is true, then make me wrong so the interpretation is consolidated? and we disagree, so how to explain the shadow as I am shallow with depth of the enthusiast <<something about clouds and hands>> tell me of the seeming smear do the dots ray instead of disrupt this water which is sky? and then the question can’t matter since this answer is different even as extension or circumvention different from your answer and I hardly spoke of the yellow Thom Young Thom Young is an artist based in Asheville and Boone, North Carolina. Their work has appeared in a few journals, while their first collection, Bespoke, is forthcoming from Saint Andrews University Press in the Fall of 2019. Pieter Bruegel’s The Harvesters: August The eye must enter this blaze of grain that comes forward out of the frame, a blond forest of ripened light. The fastened sheaves march motionless on their legs of broken gold. They are becoming the reason for this day’s work, its stack and haul, in the ocher glaze of a centuries-old afternoon the wind rises through fresh each time we look. In the distance hills slipcase into hazed air, where always there will be an ocean waiting at horizon’s edge paced by tiny pale silhouettes of ships that come and go in delicate silence. A heedless sleeper with emphatic sprawl makes himself the hub of this wheel of harvest and hungering, the closed eye of this fecund calm. His paused desires are the tight nutmeat in the shell of this moment, secure in the clutch of all that cannot resist the spiral in to sleep. Joseph Stanton This poem was first published in Imaginary Museum: Poems on Art, by Joseph Stanton, Time Being Books, 1999. Read The Ekphrastic Review's interview with Joseph Stanton, here. Joseph Stanton is Professor Emeritus of Art History and American Studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. He has published six books of poems: Moving Pictures, Things Seen, Imaginary Museum: Poems on Art, A Field Guide to the Wildlife of Suburban Oahu, Cardinal Points, and What the Kite Thinks: A Linked Poem (co-authored with Makoto Ooka, Wing Tek Lum, and Jean Toyama). Over 500 of his poems have appeared previously in The Ekphrastic Review, Poetry, Harvard Review, New Letters, Poetry East, Ekphrasis, Image, Antioch Review, Cortland Review, New York Quarterly, and many others. His awards include the Tony Quagliano International Poetry Award, the Ekphrasis Prize, the James Vaughan Poetry Award, the Ka Palapala Pookela Award for Excellence in Literature, and the Cades Award for Literature. Barbara Danin Challenge I thank all the writers who submitted poems to the Danin Challenge. There was something to admire in everyone one of the pieces. The eleven poems I’ve chosen interpret Barbara Danin’s Cadmium Sea with candor, pain, joy, humor—everything I want and need from a poem. I’d like to thank the middle school students from the Rising Leaders Academy in Panama City, Florida, too. Their teacher, Brandi Glover, had approximately 30 young writers enter poems and short stories for the challenge. Danin’s swirling waters inspired narratives about swimming and fishing, friendships, climate crisis, stereotypical ideas of beauty, and what it’s like to be an outsider. I was moved by many of their pieces. Of the students’ work, I’ve chosen two poems: Samia Albibi’s “Free Me,” which floored me with its honesty and resonance—I couldn’t stop thinking about it. I chose Artem Daibarsky’s untitled poem for its humour and musicality. Congratulations to these two young scribes. They—and all the students who shared their writing with me—have bright futures ahead. Tina Barry, guest editor ** Carry Along I swallowed her, eventually, as I did with everything else of value, for safekeeping. She seemed to understand, brave daughter, as I pressed with my thumbs, as she’d watched me do with my marital rings, her pages of dried flowers, the papers that would surely be taken. I made myself a vault to her treasure, cupping, compressing. Child. Concentrate. Now dense as gold and perfect as a nesting doll, her whole tiny person nestled against my tongue, soundless and prayerful. Or maybe that was me. Kari Nguyen Kari Nguyen’s short fiction appears online and in print, including in five anthologies. Find her: karinguyen.wordpress.com and @knguyenwrites. ** Currents Shadows drop into my hand, the river falling at sundown. Ships' horns wail on currents of muted air over would-be lovers stalled in loneliness. The river caresses its unrequited cargo. Charlotte Hamrick Charlotte Hamrick’s poetry, prose, and photography has been published in numerous online and print journals including Foliate Oak, MORIA, Connotation Press, and The Rumpus. She is a Pushcart Prize nominee and was a finalist for the 15th Glass Woman Prize for her Creative Non-Fiction. She is Creative Nonfiction Editor for Barren Magazine and lives in New Orleans with her husband and a menagerie of rescued pets. Follow her on Twitter @charlotteAsh. Website: Zouxzoux.wordpress.com ** Orpheus in the 21st Century Rivers of milk and blood flowed down from the past into the Age of Reason when the sun fell into the ocean (an elemental Enlightenment) and resources were renamed. Scientists said you came to me in melted snow and blood washed down from battle fields my identity doubled when the aborigines hummed dream songs and women on the river bank changed disguised in the colours of nature widows wore black nights of seduction and storm clouds, the winter when the pipes froze and I ate seeds of springtime in the underground pink and green and raspberry red, fleurs du temps, oceanic blue -- nothing rhymed -- scry bowls, prehistory, the Greeks. My mother wept writing to say I was too young to marry harsh reality and she missed me like sunflowers growing wild in the field where I'd left the others when I heard you singing. They say it was the river nymphs (naiads) who tore your body into pieces and sent your head floating down the river, and there were predictions by poets that your music would flow, forever, under the pens of men, and that was true -- I was your muse, years counted in hundreds while I waited, leaves falling in autumn like withered hands; young again when I write it is you calling me to be with you in the 21st century, in words beautiful and lyrical and strange changing rhythms with spangled starfish and sea urchins marine data, and a river -- the magic of light and a huckleberry moon -- this I remember Mellow Yellow, how love songs are written with broken rules Laurie Newendorp Laurie Newendorp lives and writes in Houston, Texas. Her poem won second place in the Houston Poetry Fest Ekphrastic Poetry Contest, 2018, and her work has appeared in Gulf Coast, Nimrod (runner up for the Pablo Neruda Prize), AIPF, Isotope and Dogwood. A graduate of the University of Houston Creative Writing Department in Poetry, she enjoys reading at Archway Gallery and in various museums and art installations with Words & Art. She is pleased to have discovered the Ekphrastic Challenge (her first online publications) as poetry, art, archaeology, travel, dogs, horses (actually all animals) and family are her passions. She translated ten of Rilke's "Sonnets To Orpheus" in the voice of Eurydice, and he remains another of her passions. ** Cortege & Corsage Lethe sucks my colour off, turns blood cells into silk & thinks to usher me beneath its golden scythe from which cut flower heads float down as prettily as ghostly falling doves, forgetful, blithely pounce. Tom Riordan Tom Riordan lives in Hoboken, New Jersey. ** My Country 'tis of Thee ... listen but see that pretty face drowning in scraps of our flag. That girl's not singing sweet land of liberty, not wishing the blue hobby horse carry her to a white cottage with camellias at the gate. She sees the black edge, knows it exists. This winter after cleaning my car from thick ice, my nose bled for hours, my own Bloody Sunday, not to demean the Irish massacre of 1916 but a reality check on the world that is. I became only a Nose and you my girl are only a Face. Let's fly off to Russia, visit Gogol's Nose, Kovle, dressed in an officer's uniform, pretention at its best. Leave in a flash, needing to breathe, to abandon fake identity, escape, reject rapture, nobility and fly west to Half Moon Bay, sing to the anemones floating in the sea, reclaim our souls. Next hop a flight to Pawley's Island in the east, spread out our bodies in a gazebo, see red winged blackbirds fly, waves crash up the terrace steps at high tide and watch the sun rise above the clouds, electrifying the sky, but feel the black edge, believe it exists. Mare Leonard Mare Leonard lives and works in the Hudson Valley where she is an Associate of the Institute for Writing and Thinking and the MAT programs at Bard College. Her latest chapbook, The Dark Inside My Hooded Coat, was published in 2018 at Finishing Line Press. Leonard was nominated for a Pushcart Prize for a poem published in The Pickled Body. A narrative poem published in 3Elements will be available in a national anthology in 2019. You can find her on Facebook or www.mareleonard.com. ** The Journal of Regret Even now, after all these years, I still see you float and bob, doll-like, reluctant yet resolved. In the other room, our dog howls your name, though the windows have no answer, and the panes merely tremble in response. I sit on the closet floor, every dresser drawer open, surrounded by coloured hills of worn cotton, your favorite sweater pressed against my breath. Every time I inhale, I smell flowers and dirt, unbreakable clods of regret with nowhere to bloom Len Kuntz Len Kuntz is a writer from Washington State and the author of four books, most recently the story collection, THIS IS WHY I NEED YOU, out now from Ravenna Press. You can find more of his writing at lenkuntz.blogspot.com ** Falling From the Barren River Bridge at dusk you can see the shadows climb out of the phosphorescent sycamore trunks. You think of the happenings described by falling: dusk, night, sleep, love, leaves and rain. Love. Each instance a letting go, finding a door out of the ache. The Barren passes below. What in this suspended state, makes the dark water’s whisper so enticing? Twenty-two a day, you hear. Two you know by name. Donnelly’s note mentioned the rollover, failed attempts to piece the body together, the pills. While Smitty kept his reasons to himself. Each gone and you leaning on cold metal facing it alone. If you were to fall it would be you and gravity, a private rendezvous. But those left behind would search, construct a meaning that made their own crossing possible. You know because you keep coming back Empty-handed. You keep walking, drag your feet on the latticed metal bridge to make the kettle drum sound, the sound that says you’re there in the darkness accompanied by cricket, bullfrogs, a siren wail, tires humming in harmony with asphalt and the song of men, of women, who know someone is at the other end waiting. D.A. Gray D.A. Gray’s poetry collection, Contested Terrain, was recently released by FutureCycle Press. His previous collection, Overwatch, was published by Grey Sparrow Press, 2011. His work has appeared in The Sewanee Review, Appalachian Heritage, The Ekphrastic Review, Rise Up Review, Still: The Journal, and War, Literature and the Arts among many other journals. Gray holds an MFA from The Sewanee School of Letters and an MS from Texas A&M-Central Texas. Retired soldier and veteran, the author writes and lives in Central Texas. ** Cadmium Sea It was the day that mother could not find her car, her memory swimming in red. She could not find her key. Gold is the colour of blood close up. She also could not find her shoes, or her coat. When she is a billionth of a meter will she break apart, abandon skin and bones? It was the day she lost her hat, her management, her sympathy. The day she lost her name, her best bag, half-slip, her powder, her lipstick, her brush, her feather duster. It was the day she lost her bed, her window, her dog, her voice, her footing, and her foot. When she passed the narcissi on the bank, she heard the whispering of Adephagia, more, more, more. She lost her sight, her texture, her tone, her beginning, her middle, her end. Mary Lou Buschi Mary Lou's poems have appeared in Laurel Review, Indiana Review, Field, Thrush, Lily Poetry Review, among others. Her books include two chapbooks with Dancing Girl Press, and one full length, Awful Baby, published in 2016 with Red Paint Hill. ** What the Inanimate Knows To you who are not here in an elegant terror of the next Please let us make a deal to meet up at the agreed-on Dawn of a better mythology which I allow you to write As I speculate what the inanimate knows, so gently observant And why the animate busies itself amassing towers so high. Requiring woman and water be spectacle. Sarah Sarai Sarah Sarai’s work is in Barrow Street, Sinister Wisdom, Gone Lawn, Boston Review, Cleaver, and others. Books include That Strapless Bra in Heaven (forthcoming); Geographies of Soul and Taffeta; The Future Is Happy. She lives in N.Y.C. ** Homeopathy Working with cadmium pigments—strong oranges, reds and yellows—an artist can accidentally ingest dangerous, often lethal, amounts of heavy metal poison. Homeopathy: based on the claim that what, for a healthy person, causes symptoms of disease will, in the sick, provide a cure. The premise: dilution increases potency. I wake aware of peril to my soul, my flesh immersed in swathes of orange-red and drapes of sulfurous liquid gold. And yet, my mind remains my own, afloat Ophelia-like, as calm as if begotten for a nunnery. And yet, too pale. Too still. Above me, I sense presences: I’m omened by a spread of blackbirds, shadowed by sleek beasts—or no, by black swans landing softly with a stroke of silky oils, of oily silks. A spill of pigments stains me with forbidden shades fit for a painted lady, wanton and depraved, except my face remains serene and chaste. Thus split, what hope for me? What comes, comes suddenly, comes in the form of a phrase from an earlier life: like cures like. Homeopathy. But is it sin: self curing self? So be it, then. My task, to mix a homeopathic elixir—infinitesimal bits of heavy-metal poisons—cadmium, mercury, arsenic, lead-- infused in water to stir the blood and steer the body back to health. Cadmium seems best: malleable, silver-white, resistant to corrosion. If I dilute the tincture without ceasing, like a prayer, it should reduce to less than undetectable. If so, what’s left will be almost an absence—a state known to the adept as water’s memory. Awake, I’ll retain the traces—an inner sea emblazoned and enflamed, forever lashed with gold. I’ll be invisibly entangled with exotic flowers, companioned by mysterious dark beasts. By day, a paragon saved by grace from any taint of wantonness. By night—twice saved—I’ll float, a water nymph, a liminal creature, laved in the lethal waters of a cadmium sea. Marjorie Stelmach Marjorie Stelmach’s sixth poetry collection, One Chair, One Evening, will be out this year from Ashland Poetry Press. Her work has previously appeared in the Ekphrastic Review, as well as in Arts & Letters, Gettysburg Review, Hudson Review, Image, Prairie Schooner, and others. A sequence of her poems received the 2016 Chad Walsh Poetry Prize from The Beloit Poetry Journal. She lives in St. Louis, Missouri. ** Ocean Crossing perhaps she dreams of flowers, a town with a school her eyes turned toward land and safety her mother’s fingers no longer gripping her arm lost under a child alone in the ocean, a brilliant swirl of red light spilling from the guard boat just behind the child’s head barely above the waterline Siân Killingsworth Siân Killingsworth’s poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Typehouse Literary Journal, Stonecoast Review, Glass: A Journal of Poetry (Poets Resist), Columbia Poetry Review, Mom Egg Review, Oakland Review, and others. She has an MFA in poetry from the New School, where she served on the staff of Lit. She is a current board member of the Marin Poetry Center and recently started writing poetry reviews. Read more about her at www.sianessa.com. ** Free Me America, the land of the free… ehh not so much for me, America is a torturous place. Just because I'm black doesn't mean I'm dangerous or different. My skin colour doesn't define me, I define myself. I have so much more to offer than just pulling out weeds and planting new trees. It's painful to see my friends get shot or whipped to death, and nothing happens. I feel like I'm drowning in their blood, mixed with my tears. Here in America, freedom isn't something I have. So next time you think America the land of the free, think about me. Samia Albibi 12-year-old Samia Albibi is in the seventh grade at the Rising Leaders Academy in Panama City, Fla. ** Untitled Welcome to the sea, would you Like to hop right in? if you go there in the right time you will find 29 reasons why you should not swim like it's a dream but some will pull you in. Just don't open your mouth or something might come in make sure to wear some goggles or you will have some struggles. Don't pay attention to the weird birds, they don't bite, but the fish might. Artem Daibarsky Artem Daibarsky is a sixth-grader who speaks five languages and is learning a sixth. He is a YouTuber who enjoys the martial arts. His favorite colour is neon yellow. Banquet Forensics This is not like any still life I’ve been shown before. No piles of fruit. No flowers. The beautiful dishes are there, but the food is gnawed, and crumbs, rinds, peels, shells, and crusts lie abandoned on the table. The room is dim. A shaft of light illuminates the wall and glints on the silver and swims in the greenish Roemer glass on the table. I expect to see the light quiver in the pale wine or beer the feaster left behind. The table is the foundation. Upon it, a heavy, dark cloth with tasseled edges, skewed to reveal the bare wood. A shimmery white tablecloth, embroidered edge and creases apparent, would have made an elegant backdrop for a banquet, but instead of lying smooth over the surface, it’s crumpled and wadded in the middle of the rest of the chaotic refuse as if someone wiped their lips with edge and pushed it away. A tumulus of oyster shells covers the half-bare, half-crowded table. The eye is drawn from item to item—each exquisite in isolation, in situ, they’re a Baroque trash heap. What happened here? Am I witness to the remains of a hedonistic feast, or is it something else? The eye wants to follow the painting, but my mind wants to reconstruct the scene. This table belongs to a wealthy Dutch merchant, but he’s away on business. This meal is for his wife. It’s a servant who sets the table. There is only one servant, for the lady of the house must keep up the appearance of piety and humility. The maid spreads a dark, heavy cloth over the wood to protect it from the abuse of heavy dishes. With the green runner in place, she reaches for another folded cloth. She pinches the embroidered corners of the linen satin tablecloth, then flings it into the air, guiding it through the beam of light from the window to land on the almost-black brocade. She bustles around the table, straightening the cloths and arranging them just so. She squints when the sunlight from the window gets in her eyes, but she completes the task by touch. The tasseled edging shows around the linen hem when she’s done smoothing the creases as best she can. From the sideboard, she retrieves the silver ewer, heavy and half full of water, and crowns the table with it. She uses a corner of her rough linen apron to wipe her handprint off its cold, silver belly. Next is the mustard pot and the salt cellar. She stirs the mustard with its long spoon, then settles the handle back into its slot in the lid. When she removes the cover for the pillar-like salt cellar, she sees that the salt has settled. She glances around to make sure she’s not being watched, then she pinches it into an attractive heap. Another glance and she licks a few clinging crystals from her fingertips. She sets the table with a polished pewter plate, then begins the task of arranging and filling cups and glasses. She selects a high flute glass for bubbling wine from Bordeaux, a green Roemer for pale gold wine—expensive, from Germany— a tankard for beer, and a squat beaker for blood-dark wine—cheap, from Italy. What a clutter of cups, but the maid knows that the lady of the house will require all of them, even if she doesn’t drink from all. The lady won’t want a fork—the new dining fads irritate her husband, so this household, despite adopting the use of white table linen, relies on tradition. Above the pewter plate, she places the lady’s favorite eating knife—the one with an ironwood handle hiding inside its black lacquer and filigree case, which the maid will use to cut her mistress’s meat and bread. As a companion to the knife, she chooses the Delftware finger bowl over the genuine china, because already, the Roemer has lost a mate and the high flute is the last one in the house. The lady is hard on dishes and a china finger bowl is more dear than an entire set of green glassware. The maid pours a little water from the ewer’s graceful spout and spills a drop on the cloth, turning it transparent and green like the dark brocade underneath. She moves the bowl to cover the spot, then polishes the ewer once more. Her tray on the sideboard is empty, so now she hurries to the kitchen to fetch the food. When she comes back, laden with a heavy platter of oysters, a hock of cured ham, bread and sundries, the lady is already pacing and has already been drinking. The carefully-arranged cloths are crumpled, and the naked table is exposed. There’s no chair at this table—it stands like an island in the middle of the room, so the lady can pace. The simple place setting is already ruined and the maid freezes. She can’t reorganize the chaotic table unless she sets the trays and platters down, but the sideboard is too small for her load and if she sets everything down on the table, she can’t fix the tablecloth! Her muscles burn and she worries she’ll drop something if she has to hold the trays much longer. The lady makes the decision for her--Put it down and get out! The maid flinches and the oysters nearly tip to the floor, but she saves them with a rattle of tableware and rough half-shells. The master of the house has been gone a long time, so she forgives the lady for her tone and her impious drinking. The ugly feeling of the platter sliding on the wood makes her glad she always uses extra beeswax to polish and protect the table. Relieved of her burdens, her arms feel like jelly. Where’s the pepper? And lemon—don’t tell me you forgot the lemon! She didn’t. She slips the spice out of her pocket, folded and twisted inside the pages of an old almanac, just as the lady’s husband had it delivered. The lady imagines that he measures it out himself, and she likes to unwrap the little cones when he’s gone for too long—the lady told her once when she was very drunk— so the maid never serves it out of silver or stoneware, but leaves it in the little twists of paper as she wouldn’t dare if the master of the house was present. The lemon follows the pepper, and the maid silently opens the knife’s polished case. Delicately and without separating a slice, the maid cuts the end of the lemon, then spirals the blade around the fruit and parts the peel from the flesh. The sharp scent of citrus fills the room and settles over the cold meal. Her hands will smell of citrus for the entire day if she doesn’t do any heavy work for the rest of the afternoon. She slices the ham and bread, laying neat fans of both on the plate for her mistress, but before she’s done, the lady dismisses her from the room. She’ll cut her own meat and tear her own bread if the three slices and the oysters aren’t enough. The next time the maid sees the table, the slant of light has aged by an afternoon and slid up the wall. The table is a disaster. The ewer, its base surrounded by oyster shells, and thus clearly unmoved from where it was set at the beginning of the meal, stands open. The lady must have felt the need to peer inside, perhaps hoping to find something stronger than water. The mustard pot looks like a gaping frog, its hinged lid propped open by the carelessly-placed spoon. Vinegar and pepper rime the finger bowl, which stands at a jaunty angle atop oyster shells, empty platters, and the sheath of the eating knife. The cap of the knife case hangs by its cord. The curling spiral of lemon peel dangles off the table. The lady only used a single slice. The silver tankard lies on another empty pewter plate, collapsed like a drunk in a ditch. The glassware has survived. The maid sighs and flicks the mustard spoon back into its slot, causing the lid to clash shut. Perhaps that isn’t what this painting is, but it could be. Marie Skinner Marie Skinner is a student of writing and Classics. She has been published in the 2019 writing contest issue of Sink Hollow, an undergraduate literary magazine at Utah State University. Art is her cipher for understanding herself and her life. Detta Maddalena The breeze of Galilee closed Mary's eyes, her Lord's auburn tresses waved as the troubled sea, cradling with her fingertips the air in anticipation of His beard curls. Bathing her lips with saliva that healed the blind, a gospel whispered only to her with pungent breath that made man; psalmic pulsations wounding her flesh-- seven demons each possessed by seventy, skin paving the road to Gehenna, in which He was Satan-- when He burdened her with the knowledge of redemptive poison He carried in His veins. In all the power He possessed and all the love she promised, He couldn’t mute the voice of God or His will to be spilled, anointing the cross’s every grain and gnarl-- precious blood condemned before He floated still in His mother’s womb-- to crucify her desires for God to come into her. The life that He saved with His words and changed with His love, God had tarnished with His quest making her sacrifice His body and forcing His disciple to live without a soul, to love without a heart, speak without words, and lie by His side without a body: like Him, to live to die to live reborn. The Father was testing her too: she didn’t want to learn about her soul, but how to wrangle its desires while He held her hand and looked into her eyes, heavy with the sins of the world. They would nail her heart next to His beating in His frigid cuddle-- between her empty breasts-- tears of wine after He'd resurrected, ascended to be one flesh with eternity, and saw as the world courted sin anew. When the crown of thorns hung over her bed trickling red rain for days and weeks after He was gone, she’d wish to be born in a world void of mercy in which she didn’t love Him or wanted all of the things He couldn't give her: not salvation, desire; not the Gospel of Truth, the profane. to die for His pain and eat the sin hanging on His bones. God chose Him, but why did He choose her if all He’d give her was sorrow; if He knew that He would never be His own or his mother’s, let alone hers? If He was not willing to live for her, then she didn’t want Him to die for her. What good was His blood on dead wood coated with the rotted flesh of other messiahs if not to warm her hands in His on a long night after the fire died by the shore of Magdala, while the one burning in His heart dwindled as He gazed toward Gethsemane? Jose Oseguera Jose Oseguera is an LA-based writer of poetry, short fiction and literary nonfiction. Having grown up in a primarily immigrant, urban environment, Jose has always been interested in the people and places around him, and the stories that each of these has to share. His writing has been featured in The Esthetic Apostle, McNeese Review, and The Main Street Rag. His work has also been nominated for the Best of the Net award (2018 and 2019) and the Pushcart Prize. He is the author of the forthcoming poetry collection The Milk of Your Blood. Jenny Hears the Train The thrum of the diesel in the distance and the sound of wheels on rails, steel to steel, makes me want to go, to get out of town, to leave the life I have and try for something new. I hear the train while I am fixing breakfast, its sound coming over the houses and in my open window, pitch rising as it picks up speed, and I imagine myself lifting off, like a bird you know, and following it. It would be a long fat worm from my vantage. Sometimes, dreaming like that, I let the eggs go from over easy to solid through and the biscuits go brown and dry and hard and then I hear the sounds of complaint, dissatisfaction-- not words usually but descending sighs and maybe groans like a train approaching, slowing. That's pretty much all I get, sorry silent disapproval whenever he's here. Of course, it could be way worse, he could be a hitter like my own daddy was, and I'll take this cold hell to the hot hell my mama lived. I guess til I grow wings I'll have to live this life I chose when I was 16 and afraid I'd have no life. Cecil Morris Cecil Morris retired after 37 years of teaching high school English in California. Now he tries writing himself what he spent so many years teaching others to understand and enjoy. In his newly abundant spare time, he has been reading Sharon Olds, Tony Hoagland, Naomi Shihab Nye, and Morgan Parker. He has had a handful of poems published in English Journal, The 2River Review, Poem, Dime Show Review, The American Scholar, and other literary magazines. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|