|

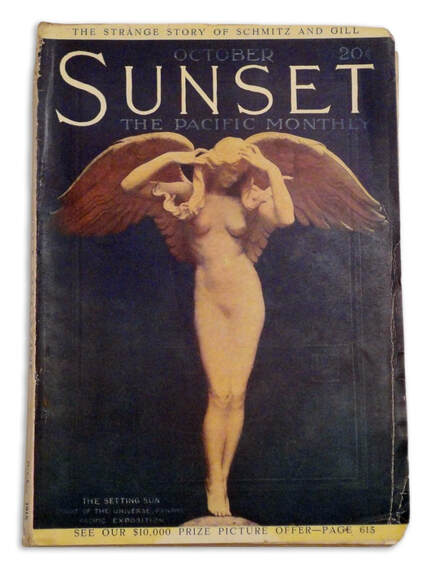

Butterfly/Moth Audrey Munson (1891-1996), the first American supermodel, was the subject of inspiration for the most exceptional artists of her day in works fashioned in oil, bronze, and marble. At age forty, she was institutionalized and spent the next 65 years of her life in one of several asylums. There remains a question about whether psychological incarceration was necessary. St. Lawrence Psychiatric Center Ogdensburg, N.Y. She was no one and once more, no one. Only briefly did she matter, held captive in a hundred poses, limbs frozen in classical form, enduring the mind’s long exercise in being other. The absence she wreathed in memory like the entrance of a seasonal greeting, an entry finding once more the props of her life-- a sparsely furnished studio with its pedestals, drawing table, chisel, knife, hammer, drapery, and all an invitation to art. What of her was caught in the silence of forever, in the eternity of beauty? And what was left? The gypsy’s curse predicted fame and penury. She had lived the prophecy. She struck a pose, transitioning to another, and another: Spring … Star Maiden … and finally … Descending Night … Her life was like Night with wings enfolding dreams, smothering them. Her reflection, hatcheted in a small three-panel mirror, was missing an arm, a leg. She could be sold piecemeal. Lamb chop! Lamb chop! The amber light began to shift. She rearranged her embroidered shawl, sprinkled with flowers, colors dulled by age. At breakfast, she stroked her face with milk, dipping her finger into her bowl of Cheerios. And then again. Her skin must be luminous. This morning she will knock on familiar doors, seek work. Later, she pulled her best frock from the bare closet. The mirror smiled back at her in complicit fun. Ann Power Ann Power is a retired faculty member from The University of Alabama where she worked as coordinator for the Bibliographic Instruction Program, University Libraries. She enjoys writing historical sketches as well as poems based in the kingdoms of magical realism. Her work has appeared in: The Pacific Review (CSU, San Bernardino), The Puckerbrush Review, Limestone, Spillway, The Birmingham Poetry Review, The American Poetry Journal, Dappled Things, Caveat Lector, and elsewhere.

0 Comments

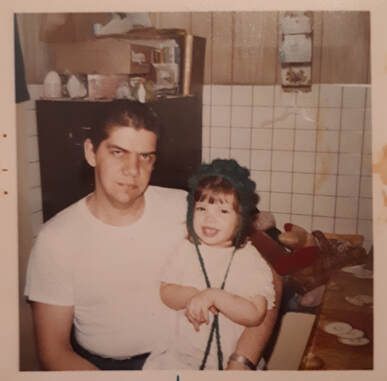

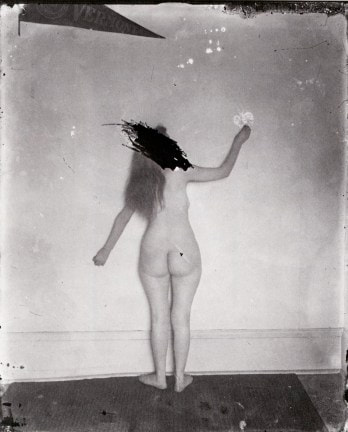

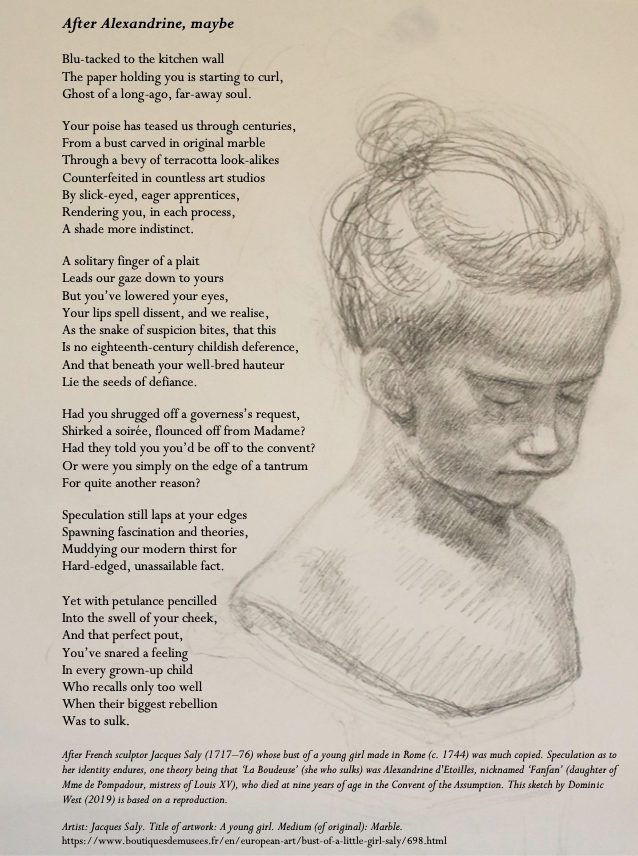

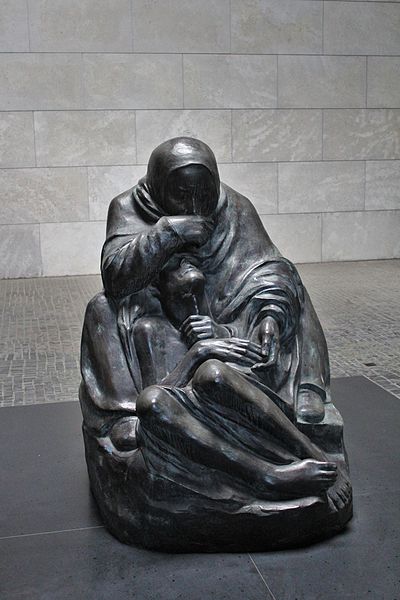

Call for Throwback Thursday selections! Be a guest editor for a Throwback Thursday? Pick around 10 favourite or random posts from the archives of The Ekphrastic Review. Use the format you see below: title, name of author, a sentence or two about your choice, and the link. Include a bio and if you wish, a note to readers about the Review, your relationship to the journal, ekphrastic writing in general, or any other relevant subject. Put THROWBACK THURSDAYS in the subject line and send to [email protected]. Along with your picks, send a vintage photo of yourself, too! ** The Estate of Ideas, by Kurt Cole Eidsvig Eidsvig on Rauschenberg. “There is never enough; there is always too much.” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/the-estate-of-ideas-by-kurt-cole-eidsvig ** You Don’t Have to Like Braque, by Edwin Rozic “When we crouched in the tall grass, feeding/ the pink-tongued, butterscotch foal…” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/you-dont-have-to-like-braque-by-edwin-rozic ** Elegy for the Luminous, by Laura Glenn “Poised leaflike on a stem, the subtle butterfly’s beyond delirium.” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/elegy-for-the-luminous-by-laura-glenn ** The Green Blouse, by Barbara Crooker “…a girl with a blouse the colour of summer…” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/the-green-blouse-1919-by-barbara-crooker ** The Pen of Plenty (or A Portrait of an Artist as the Entire Universe) by Boris Glikman “I was all of thirteen years old when the Hand from Above bestowed the Pen of Plenty upon me.” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/the-pen-of-plenty-or-a-portrait-of-an-artist-as-the-entire-universe-by-boris-glikman ** Ox Carcass, by Colin Pink “…death hangs heavier than we pretended…” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/ox-carcass-by-colin-pink ** Forest Song 2, by Pitambar Naik “…the forest songs of hope…” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/forest-song-2-by-pitambar-naik ** You Gotta have Heart, by Deborah Guzzi “…we came into the light, of knowing, of naming…” https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/you-gotta-have-heart-by-deborah-guzzi ** Ekphrastic Writing Responses: Henry Darger Laurie Newendorp, Sandi Stromberg, Janette Schafer, Kerfe Roig and more respond to the world of Henry Darger. https://www.ekphrastic.net/ekphrastic-journal/ekphrastic-writing-responses-henry-darger Psyche of Storyville Naked, nameless, face erased, she draws a butterfly to lift her up,up, up above the slate-gray roofs of Storyville, above the Blue Book beauties in white-lace slips and gartered stockings, lips rouged red for more than kisses, above madam’s silk and feathers, pimp in fly fedora, folding razor in his shiny, high-top boot, above the taunts and slaps, the blackened eyes, the burns of cigarettes, the hazy lies of opium, above the “slavish trade of mortal life” she sees the chariot swing low and hears the trumpets blare, somewhere above her shame, above her pain, above the camera’s leering eye Brian Kates Brian Kates, a longtime newspaper man, holds a Pulitzer Prize, George Polk Award for editorial writing and Daniel Pearl Award for investigative reporting. His book, The Murder of a Shopping Bag Lady, was a finalist for Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Allan Poe Award in non-fiction. Two of his poems were published in The Ekphrastic Review in 2019. Other poetry has appeared in Third Wednesday, Common Ground Review, Poem, Red River Review, Modern Haiku, Frogpond, bottle rockets and cattails. He lives with his wife in a house in the woods in the lower Hudson Valley. The Day They Sold Deucey Henry’s eyes cavern dark in disbelief, his smile shades a faded frown. His white five-and-dime t-shirt mucked down to his groin from where he cuddled Deucey, his muddy goat-hug an apology, until father told him “let her go.” His knees knock together like a pair of chickens that back away from danger. He won’t say cheese. Kaye stands tall as two fenceposts, proud to pose. Shoulders taut from raking steer manure, like her father taught her, leaving traces on her face and hands. Her hair plaited in two blond braids skinny as sticks, then pinned over her head like a cock’s comb. A princess’s crown, her mother corrects her curtly. She clutches the thighs of her overalls, stretches their sides to curtsy. Pantleg slits like the holes in hens where the eggs emerge, spilling into the nest, or breaking on the ground if they’re unlucky. The hens peck away at the shell and muck, unaware the egg was once their chick. Jill Witty After 15 years in startups, Jill Witty decamped to Florence, Italy, where she is writing her first novel. Her short fiction has appeared in Atlas & Alice, Defenestration, Reflex, and Flash Fiction, among others. Connect with her at jillwitty.com or on Twitter @jwitty. horrible decree Brian A. Salmons Brian A. Salmons is a writer and translator from Orlando, Florida. His work has appeared or is forthcoming in Eyedrum Periodically, Arkansas International, Levee Magazine, Mantis, NonBinary Review, Memoir Mixtapes, Sunlight Press, Poets Reading the News, O:JA&L, The Light Ekphrastic, Eratio, and others, including anthologies from YellowJacket Press and TL;DR Press. He also hosts The Ekphrastic Review's podcast, TERcets. Beyond the Window Panes I eat plums by moonlight, wearing a tulip vase crown. We haven’t left the house in days. Outings are for bread and milk during this time of quarantine. Every room becomes a scene from a painting, an imagined destination. I move about for the self-created surprise of a change of landscape. The kitchen becomes a noisy café, where I eavesdrop on lovers sharing a slice of cake. The sitting room becomes an art museum gallery. I sit on a bench, gazing at the walls, seeing framed oils of sun-blazed fields and reclining women on velvet. Every window is a passageway. The outside looks in and I reach out to touch the towering trees with longing eyes. Walks are allowed. I can’t get very far. So I take long strides, journeying in the mind down a highway that leads from coast to coast. My feet become wheels. I drop the plums, increase my speed, feel the wind in my hair. I am finally beyond the window panes. Cristina M. R. Norcross Cristina M. R. Norcross lives in Wisconsin, is the author of 8 poetry collections and was the editor of Blue Heron Review (2013-2020). Her latest book is Beauty in the Broken Places (Kelsay Books, 2019). Cristina’s poems have been published, or are forthcoming, in: Visual Verse, Your Daily Poem, Right Hand Pointing, Verse-Virtual, The Ekphrastic Review, and Pirene’s Fountain, among others. Her work also appears in numerous print anthologies. She has helped organize community art and poetry projects, has led workshops, and has also hosted many open mic poetry readings. Cristina is the co-founder of Random Acts of Poetry and Art Day. Find out more: www.cristinanorcross.com Denise O’Hagan

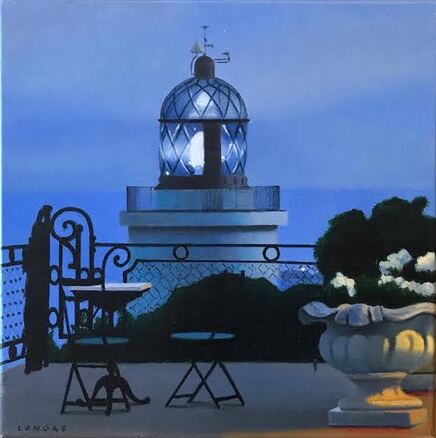

Denise O’Hagan was born in Rome and lives in Sydney. She has a background in commercial book publishing, manages her own imprint BlackQuill Press, and is Poetry Editor for Australia/New Zealand for Irish literary journal The Blue Nib. Her poetry is published widely and has received numerous awards, most recently the Dalkey Poetry Prize 2020. Her debut poetry collection, The Beating Heart, is published by Ginninderra Press (2020). https://denise-ohagan.com El Far (The Lighthouse) There’s a woman inside the lantern room. Her hair blinks whitely. She has lived inside the glass for decades on air on light on visions of clouds banking the horizon. She has nothing to do with what happens at the small table and two chairs behind her in the dusk which lasts for hours in summer in this latitude. She’s aligned with the meeting place of air and ocean, doesn’t care about the ghosts of dark green plants, didn’t see the man and woman who went in to throw off their white robes. A ship’s light rides too close to where her spectral locks give warning, but she can’t help what self-destructs behind her or below. Penelope Moffet Penelope Moffet’s most recent chapbook is It Isn’t That They Mean to Kill You (Arroyo Seco Press, 2018). Her poems have been published in Natural Bridge,Permafrost, Pearl, The Rise Up Review, The Sow’s Ear Poetry Review, The Ekphrastic Review, Verse-Virtual, The Missouri Review and other literary journals, as well as in a number of anthologies. She lives in Los Angeles and works as a legal secretary. The Kiss His arms support her in the black-and-white world of a February Paris morning. She leans back but not completely. She still does not know how strong he is, how far to trust him. Not too far. While his right arm pulls her back, while he plants a kiss on her face, his left hand clutches the leather bag, ready to move forward toward the train. Maybe to work. Maybe away, just away. To create distance from the sheets that swaddled them. To inhale the perfume -- still too fresh -- on morning secretaries and the scent of cigarettes. I am in the shadows behind his left shoulder. I woke early to come here, slipped out of a bed that still smells of him, although the sheets have been washed weekly for months. My father said, “Don't go. Don't tell him,” and I am still deciding when I see him reel her in for one last kiss. Don't trust him. Don't lean too far back, I want to whisper. He'll drop you, and the ground is hard. Part of me wants to see her fall. I know what is in the bag. He never leaves anything, not a toothbrush, not a comb. Nothing that lasts. Do I stop him? Do I tell him? How sweet to foil his perfect record! But the ground is cold and always hard. I don't want to rip my skirt if I tumble. I could just sit down and tell him. What a sight: me, sitting on the ground of a Paris metro, saying, “Look down here. This woman, on the floor like a child, once loved you. Do you remember her?” Quickly people are moving, pushing. I hold onto the railing so they won't carry me with them. I wish I had worn gloves. “I'll see you at six,” he says and squeezes her hand, but the bag is already on the train, and he follows it as he always has. I tried to keep it once. “We are having dinner tonight,” I told him. “How silly to take it with you!” All he said was, “Life is full of surprises.” The door closes, and the train strains down the track. An older man looks sadly after it. He will have to walk. She moves toward the stairs and looks suddenly drained, black and white, like too much sun causes too much shadow. He has that effect on people. His mother once told me he leaves her in joyous exhaustion when he calls. My joy is tired. Too much life without rest can age you. And still I walk a block behind her, studying her back for a burden I lost and still miss. I want to say, sister, take warning. But she is not my sister, and life is full of surprises. After all, the bag could stay one day. Not in the morning. It is easy to have him in the morning. Only when he stays for lunch will he be home. She steps into a brown brick building, and I must return. I am sculpting today. A man riding a leather bag down a hill. At the top is a castle. The carved edges will play shadow and light. It will be small enough for a child to reach. Deborah Edler Brown Deborah Edler Brown is an award-winning poet, writer, journalist, and author. Her work has appeared in Nimrod, So Luminous the Wildflowers, poeticdiversity, Altered Lanes, Blue Arc West, and Sisters Singing: Blessings, Prayers, Art, Songs, Poetry & Sacred Stories by Women. Her poem “Cubism” won Kalliope’s Sue Saniel Elkind Poetry Prize, and her fiction has been twice nominated for the Pushcart Prize. Deborah was born in Brazil and raised in Pittsburgh. She resides in Los Angeles, where she is busy building communities among characters and readers. Throbbing with Life "For me, time stood still during the war. It would not fit in to anything earthly. She hovered. I wanted to reproduce something of this feeling in this figure of fate floating in emptiness.” Ernst Barlach Three years earlier, I had been one of a set of American graduate students invited to teach English to future high school teachers in the former East Germany. While there, I naively let my student post an article on the bulletin board about “Good Girls in the Soviet Union.” Sarcastic criticism of such girls for believing what the government said did not go down well with the authorities. Despite my pedagogical faux pas, I was invited back in 1988 to teach master’s students at the University of Rostock, then named for the Communist hero Wilhelm Pieck. My handler was in charge of entertaining me and to make sure I didn’t bring down the regime—or the English Department at any rate. So that first night, he asked me if I’d like to meet his friend Bernhard the next day. The nearby coastal resort had a sauna and wave machine. Sure. I’m up for anything. Why not? That Sunday, we take the S-Bahn and stroll through picturesque Warnemünde to the Hotel Neptune. In the lobby, my handler makes introductions. “Bernhard, Susan. Susan, Bernhard.” We shake hands politely, as all good Germans do. Three minutes later we are all stark naked. Families and friends walk unselfconsciously around with children playing and enjoying themselves. No shame in this northern European haven of extreme temperatures and casual nudity. As the warm mist billows around us, Bernhard and I become quite friendly, given our penchant for standing up to one another’s opinions and enjoying disputation. He wants to leave East Germany to be a business man in South Africa. “South Africa is a wonderful place where a man can make his own way in the world.” “If he’s white,” I point out. This romanticization of political oppression, of a different sort than in his native German Democratic Republic, infuriates me. His not being bothered at all by apartheid would have gotten me hot under the collar, if I’d had one on in that sweltering sauna. I want to convert him to my political views. Sheltered as he is, where the only people of colour he sees are Angolans or Cubans on the S-Bahn on their way to factory jobs, it is hard going. That eventually Bernhard would come to the United States to study engineering, only to court and then marry a woman from South America, is impossible to predict as we sit on fragrant spruce benches, stripped bare to the skin. It is also impossible to imagine that I would one day read a copy of my own secret police file, which neglects to mention my exposed dishabille in a steamy sauna. One day, Bernhard and I take a train to Güstrow. There, we visit the home and atelier of the Expressionist artist, Ernst Barlach. The orangey-red local brick of the chapel-like building is typical of Mecklenburg in northeastern Germany. For this fan of South Africa, Bernhard spouts forth harshly about Nazi persecution. “They called Barlach degenerate. Because he was anti-war.” Ugly-beautiful figures shimmer in his atelier. The beggar with crutches. The laughing old man. The cruciform pietà, with the mother embracing her helmeted son. I have never seen art like this before. Gothic but Expressionist. Ancient anguish at the terror of war with twentieth-century gas masks. Harsh but exquisite. At the nearby cathedral, likewise of brick, the stark Lutheran heritage perfectly frames one of Barlach’s most famous achievements, called The Hovering Angel or The Floating One. I gaze at her face: eyes closed, mouth turned down. Is she sad? Beatific with her arms crossed against her breasts, she transcends sex. The pleated gown gathered about her feet lends modesty and dignity. She soars above us, serenely. Bernhard, a true son of the area, proudly explains. “One of the castings was hidden during the war. Another was destroyed in a bomb attack in Berlin.” The plaque states that the face resembles that of Barlach’s friend, his fellow artist and pacifist, Käthe Kollwitz. Her own anti-war art brought her to the attention of the National Socialists. Threatened by the Gestapo, she was protected only by her fame. Barlach is said to have only realized it resembled Kollwitz once he was finished fashioning it: “Had I wanted something like that, I would probably have failed.” As we leave, I see the floating figure out of the corner of my eye, protecting me. That night, Bernhard and I feast on venison and buttermilk potatoes at a local Schloss, washing them down with a foamy Rostocker Pils. Years after the Berlin Wall is breached, Kollwitz’s peace memorial replaces the eternal light at the Neue Wache. It sits on Unter den Linden in the reunited Germany’s newly designated capital. Buried there are an unknown soldier and a concentration camp victim. While before there had been goosestepping for citizens and tourists, now the mourning mother sits, cradling her son home dead from the trenches. Rain swoops south from the Baltic, dripping through the oculus above her in chilly Brandenburg. Could it be a tear glistens on her cheek? Does she lift her head to gaze into my eyes, holding them still, entranced with her profound grief? Everything throbs with life in Berlin, even the departed. Susan Signe Morrison Susan Signe Morrison, a professor of medieval literature at Texas State University, has published scholarly books, a novel, and poetry. Having taught in the former East Germany in the 1980s, she is currently working on a book about her Stasi (secret police) file which has some unusual—and false—assertions. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|