|

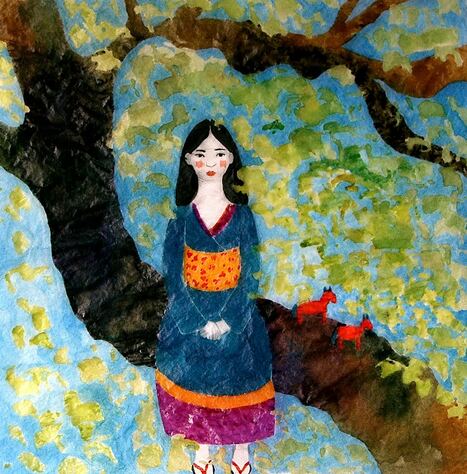

After Paul Delvaux’s The Village of the Mermaids 1942 to weave ocean-coloured gowns from tangled nets took hours, occupational therapy at the mermaid’s retreat. with our hands folded, cabins locked, virtues preserved, the watchman checks on us; our wide-eyed stares belie other lives. he doesn’t know our fins wave wildly as our tresses beyond these civilized walls that shield landlubbers from tsunamis. women imagine they are us, riding waves, free to frolic, but we imagine being mortal, too, belonging somewhere, the sun slicing our days. it’s here we catch our breaths, meditate on salty, fluid blessings, more numerous than seashells on the beach, before merging once again with our deep. Cynthia Gallaher Cynthia Gallaher is a Chicago-based poet and playwright, is author of four poetry collections, including Epicurean Ecstasy: More Poems About Food, Drink, Herbs and Spices (The Poetry Box, Portland, 2019), and three chapbooks, including Drenched (Main Street Rag, Charlotte, N.C., 2018), poems about liquids. She made a 10-city book tour with her nonfiction guide & memoir Frugal Poets' Guide to Life: How to Live a Poetic Life, Even If You Aren’t a Poet, which won a 2017 National Indie Excellence Award.The Chicago Public Library lists her among its “Top Ten Requested Chicago Poets.”

0 Comments

Thank you to The Ekphrastic Review contributor t.m. thomson for sharing this photo of some of her favourite things.

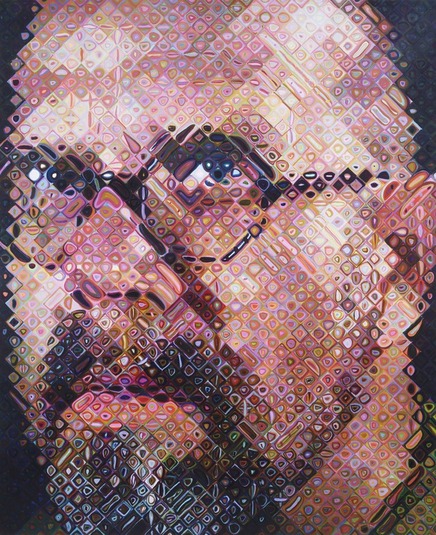

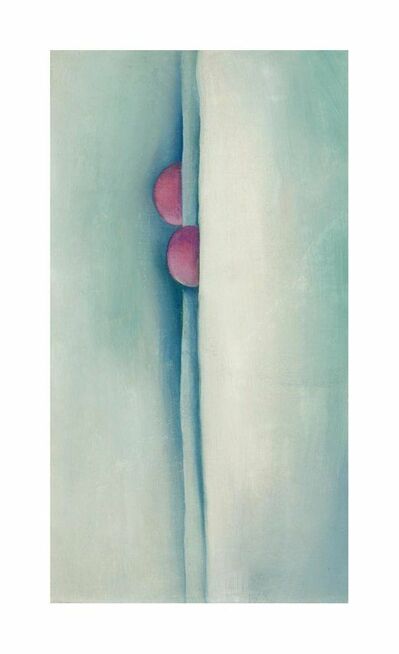

You can also get a spiral notebook or hardbound journal featuring a variety of artwork designs by Ekphrastic editor Lorette C. Luzajic. The journals are perfect for all your future ekphrases, and your purchase supports the maintenance, development, and promotion of The Ekphrastic Review. Thanks to all who have bought theirs already for your help and support. Click here to see them all. Facial Blindness ~for Chuck Close Pencil lines square off A face doomed by a certain blindness Where no paint stroke equals hair and no mouth is yours You—are sienna scumbles vermillion daubs Only a stab at pupils and pores yesterday’s Fu Manchu Perhaps no pigment clinches facial recognition May I present to you lozenges green and umbra Oil mingled in soft dirt not exactly Resemblance more a work-around For prosopagnosia* awareness without emotion The rind-and-peel after-taste of pungent cerulean A wink of capricious colour Shaped like a simile Sidling up to a mirror Susan Cowger *prosopagnosia: the inability to recognize faces of other people or one’s own features in a mirror Susan Cowger’s chapbook, Scarab Hiding, was released December 2006. Her work most recently appeared in Windhover, Adanna, Perspectives, CRUX, and McGuffin. Susan is founder and past editor of Rock & Sling: A Journal of Witness. Total War on the Highway of Death -Highway 80, February 26-27, 1991 Schwarzkopf lied about what was on the road; he tasted smoky ruins, flaming flesh. Like the fraud of the future with his thugs, this ranking swine voodooed his own rapists from butchered people in Toyota vans. * I’m staring out at a November sky. Toys, dolls, hairdryers on Highway 80, and smoke, and incinerated bodies. I imagine this dank November day is brilliant compared to the Mile of Death. * Softest rain through bare November branches whispers an illusion that sounds like peace, as if the Saviors decided to take away everything that wasn’t solemn, leaving us with quiet close to silence. * Desperate for home when the carnage began; overturned cars and trucks, wheels still turning, radios playing, bodies on the road, the ghost infested smoke trying to rise. Soon, redeemers plowed dirt on the living. * Obstacles? Mines, barbed wire, and human, rift sector, great checker of surrender. Someone leapt from a car and tried to run. He was shot, and a bus of children bombed. In total war you leave nothing behind. * Schwarzkopf lied about what was on the road -- Toys, dolls, hairdryers on Highway 80, as if the Saviors decided to take the ghost infested smoke trying to rise? In total war you leave nothing behind. ** Stuck in Traffic on the Highway of Death -Highway 80, February 26-27, 1991 Highway 80, six lanes of death going both ways, Clusters of Rockeyes blind to what the loathsome weigh. A-6 Intruders bombarded the head and tail of the vast column; brimstone blew all oaths away. 2000 vehicles and more bodies than that -- though many escaped across Euphrates’ ghost quay. If, on the Mile of Death, you survived the sky’s rage, you were taken on the ground, corpses smoked away. Vehicles and soldiers smoldered in the hot sand. Nighttime bombs lit you up; charred, you were shoved away. The Battle of Rumaila, or the turkey shoot - - Battle of the Junkyard. Battle of the Causeway. Saddam’s 8,000 men and his 200 tanks. Rancor in sweat down their faces – they’d live this way. I saw them, small silhouettes on the TV screen. In backyards here children played the I give up game. It’s the race to a new life, the let’s start again. Many times, John, the shrapnel brightly heaved away. John L. Stanizzi These poems are from the author's collection in progress, Feathers and Bones. John L. Stanizzi is author of the full-length collections – Ecstasy Among Ghosts, Sleepwalking, Dance Against the Wall, After the Bell, Hallelujah Time!, High Tide – Ebb Tide, Four Bits – Fifty 50-Word Pieces, and Chants. His poems have appeared in American Life in Poetry, Prairie Schooner, The New York Quarterly, Paterson Literary Review, The Cortland Review, Rattle, Tar River Poetry, Rust & Moth, Connecticut River Review, Hawk & Handsaw, and many others. The Closet

Most of the time Ellen dreamed, she dreamed of lovers who moved on, who once celebrated her in poems, or songs, or brought her gems or flowers or joy or promises but in the dream are completely indifferent, stoic, a boy-man presence who was there solely to remind her that she simply wasn’t enough. Lately, when Ellen dreamed, she dreamed of closets: her parents’ walk-in closet with the spilled light on the floor and her mother’s ironed shirts and her father’s rifles under glass; her childhood room closet with a sliding wood door that once unveiled a performance of vibrant, animated puppets inspired by scarlet fever; her ex-boyfriend’s closet where he kept his pants rolled up like torpedoes. The only closet in her recent apartment had a well-made door that was painted a dozen or so times throughout the centuries and now matched the linen white of the McIntire trim. On the door hung a framed print of Lydia Cassatt, Leaning On Her Arms that gave off an aura in the dark, and Ellen often stared at that print thinking of her father and how that was the last thing he carried from his truck before the cancer took him. Lately, she had heard tussling in the closet, just before falling asleep, at the portal of a dream. Too drowsy to get out of bed, she reasoned that it was a mouse; the apartment in which she lived was part of a ship captain’s home, built in the seventeen hundreds (before Lydia’s time) and had its generations of mice (she had caught several in a have-a-heart trap.) It was not logically possible for a mouse to make such a ruckus, but the near-dreaming mind is not a reasoning entity. Most nights, sleep came swiftly, surreptitiously stealing consciousness as Ellen read or watched the evening news. Her days keeping teenagers on task, grading papers, planning lessons, braving cafeteria duty and spit balls, not-so-clandestine note passing and insufferable parents made sleep seem like a refuge. But on one particular night, there was a loud bang and she sat up. She turned on the light. Outside there was a voice, someone—her neighbour Joscelyn—smoking a cigarette and talking to her friend on the phone. Ellen and Joscelyn weren’t particularly close, but they shared a certain loneliness known only to single women in their twenties and were often company for one another on a Friday night when neither had any plans. Ellen smelled the smoke from below, carried by a warm late spring breeze, and felt comforted that Joscelyn was there, nearby, within calling distance, just as her father was nearby when he was mowing the lawn on a summer evening and her mother put her to bed while there was still light. She was lulled back to sleep by Joscelyn’s conversation, and dreamed of an ex-lover; he was working in a coffee shop as a baker. When she visited with a friend—a dream friend, no one she had ever known or seen in her waking life—he talked only to the friend and passed her his number on a paper napkin, the creases of his palm caked in flour. The next night, after reading a paragraph from a novel and then drifting off, she heard knocking. She thought it was coming from her dream where her father was moving her furniture. Her eyes snapped open. She sat up, turned on the light, kicked the covers, stood up, walked over to the closet. She stared at Lydia in her haze of chartreuse and waited, noting the romance of the chandelier—Lydia must have been at a theater. Was she with a gentleman? Ellen grabbed the doorknob, turned it, and flung Lydia aside to witness her calm and composed clothing, her imperturbable shoes. Ellen went to the mirror and examined her face; she looked ill. She felt a panic start to rise up. This closet bullshit was causing her to have interrupted sleep; often she stayed up for hours thinking about lesson plans or parent calls before she could drift off again. She could get into an accident after all, swerve off the road, half asleep. She took a pill, went to bed, and slept soundly, woke up without irritability, without the hollow yearning that comes from witnessing an ex-lover’s stoic and discriminatory behavior or the maneuverings of a ghost. It was early Sunday morning when she saw the light coming from under the closet door. It matched the light coming from the window—the diffused light of approaching summer that held within it the titillating notion of possibility. The closet door slowly creaked open and a figure stood before her. The figure told her not to be afraid; it—he—she interpreted it as a he—was full of love. Ellen felt as if she were in a warm swathe and was comforted, despite the fact that the figure had no recognizable face and seemed only to be mimicking a male human form. He communicated without words, wanted to embrace her. Ellen was hesitant. There was the question of trust. But the heart part of her, the part that was eternally hopeful, inspired her to rise from the bed in a celestial leap and land in the figure’s would-be arms. She leaned in and kissed him, as she did that night he made her dinner, under the stars in the skylight and the moon, and he welcomed her embrace and she was filled with ecstasy, every bone, every cell, ecstatic. Her mind rewound to: No. He had driven away, left her on the sidewalk, despite running his hands over her leather jacket moments before and telling her they should keep in touch. She pulled, coaxed her spirit with visions of movement, of memory, of standing, of walking, even dancing, but her soul could only stretch the chord so far. Eventually the light moved on, became less brilliant, and Ellen returned to the body, to all that is laden and foreseeable. Laurette Folk Laurette Folk‘s fiction, essays, and poems have been published in upstreet, Waxwing, Literary Mama, Flash Fiction Magazine, pacificREVIEW, Boston Globe Magazine, among others. Her novel, A Portal to Vibrancy, was published by Big Table in June 2014 and won the Independent Press Award for New Adult Fiction. Totem Beasts, her collection of poetry and flash fiction, was published by Big Table in May 2017. She is a Best of the Net and Best Small Fictions nominee and graduate of the Vermont College MFA in Writing program. www.laurettefolk.com Corollary There are mornings, more mornings now, when I try to separate love from myself. I describe my face to the silence as a stranger would, to another, after a brief encounter. I describe my love to the mirror as a bird would explain light to another, in the dark. I describe our time together as a fish would talk of wetness to another, not knowing. Your fingers comb through the lines, trying to distinguish reason from craft. But a poem is only a corollary. A consequence that has subsumed its cause. The glass in our window is neither inside nor out. The sky becomes a sky only when we look up. You describe distance to me as a road would to another, as a beginning or ending. Rajani Radhakrishnan Rajani Radhakrishnan is from Bangalore, India. She posts her work on thotpurge.wordpress.com. Her poems have recently appeared in the Parentheses Journal, the Poetry Annals Anthology –Anatomy of Desire, The American Poetry Journal and Abridged. The moon had chased the sun that day* until there were two there, two spheres leaning in to each other two halves bisecting the clouds and waves to take me off into a new world, a different sea of blue with peach, with orange hues of loosened slopes, no longer darkened lines or alarming truths of empty space. Or was it the moon that dimmed the hour as I lay on that air of clouds, without weight, without sate of soul in the wait of full light, in the wish for a sign of star, a future shine to brighten my sky, my foreboding day? Judith Brice *After Georgia O’Keeffe's Green Lines and Pink, as viewed, inadvertently, horizontally. Judith Alexander Brice is a retired Pittsburgh psychiatrist whose love of nature, experiences with illness, and outrage over political issues has informed much of her work. Her over 50 published poems have appeared previously in The Paterson Literary Review, The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Vox Populi, Versewrights, The Magnolia Review and Light, a Journal of Photography and Poetry, and more. One poem, "Questions of Betrayal," is part of the permanent collection of the Holocaust Memorial Center in Farmington Hills, MI. Dr. Brice’s first book of collected poems, Renditions in a Palette, was published in 2013 by David Robert Books. Overhead From Longing, her second book, also by David Robert Books (Wordtech Communications), was published in August, 2018. One of the poems, "Mourning Calls" has been set to music by Michigan composer, Tony Manfredonia. Its performance, (Pittsburgh, PA, December, 2017 by Tuesday Musical Club) can be found at https://soundcloud.com/tony-manfredonia/sets/mourning-calls. Judy divides her time between Pittsburgh, PA and Petoskey, MI and delights in her life with her husband, poet Charles W. Brice, their substandard-standard poodle and two cats The Noble Working Men: the Navvies Prologue The navvies are resident in a still life, shovel, dig and mix without a stop, spades and picks unzip the road in Heath Street, Hampstead, London, where they prop and shape a gaping hole in the busy road, dig water trenches for the powerful and rich though the poor still carry pails to their abodes from wells or pumps on cobbled streets, which one day, perhaps may change for their houses. The navvies are fenced in and passers-by are kept behind the barriers – the work arouses indifference, theirs not to question why. The navvies are hot. The sun shines on their faces a canopy of sky squeezes between the spaces – a canopy of sky squeezes between the spaces, of leaning trees. The navvies are scrutinised for ever. We see but do not hear the commotion, the scrapes of shovels against the scarp, how the men never cease their idle chatter or pearls of laughter. We don’t hear the peals of bells, the insincere threats and barks and growls of the dogs who loiter. We see, but do not smell the scent of sweat, sodden shirts and kerchiefs, faces burnt from working in the heat of summer sun as they strain and stretch and are subservient until the end of day when work is done. The painter doesn’t consider them to be too vulgar for his art for everyone to see – Adonis Adonis is not too vulgar for all to see, our painter’s enamoured by his theatrical stance, he is the centre piece, his poise carefree, his gaze fills the central space, a glance towards the artist, mocking, a rose clamped between his lips, improbable in real life – brought to mock the painter? Will it be stamped on, as in an opera? Petals shred with his knife? He stands in a pose of perfect equipoise clean-shaven, striped kerchief, a length of white shirt over his brown corduroys held up by a wide red sash. His strength is limned, his portrait painted, his destiny is set down by our painter for posterity – set down by our painter for posterity, then a scintillation of light illumes him. He stands on a raised platform above the other men. He piles up the earth, the quicklime and the sand. What is he thinking up there in the limelight? Is he waiting for the day’s work to be done to go with his pals to the tavern, eat a bite of food before returning to a wife, mother or none of these? His has become a rifled life but it is doubtful he knows the ancient myth of Adonis, the epitome of beauty, the strife that surrounds his newly-given name, the acroliths built to worship his fame. Adonis in the flesh knows nothing of this – a common working wretch – he knows nothing of this – a common working wretch, a lowly born man, but worthy of his depiction as he tears a hole in the street, carrying and fetch- ing, symbolically ripping society’s fiction – disrupting the social hierarchy by chance. He watches the ragamuffins play nearby calls to his mates, casts an occasional glance at our painter, and the people passing by. Adonis a sobriquet, not his real name, he is a Bill or Fred or possibly a Jack not a god, but a worker – just the same as the other men. Our painter attacks – believes that idleness is the devil’s chicanery but favours the navvies with great integrity– The Shoveller our painter endows navvies with integrity– he has given the shoveller some sense of style a red and yellow cap, though bowed in servility, as he bends over double, shovelling, to pile the rocks and earth, sieving the quicklime, the powder accumulating on his left unaware of the problems that ticking time could bestow on him, leave his wife bereft if he develops breathing difficulties later on or be unable to stand up straight and tall. He leans on his spade in languor, wanton, a hint of smug, certainly not in thrall to Adonis. His cement-spattered boots a token by the painter, the worker’s status is unspoken The Ale Drinker to the painter, the worker’s status is unspoken, though the hefty navvy, the thirsty ale drinker at the apex of the painting, his thirst now broken is a follower of Dionysus and no great thinker, just shoulders his hod, a big beefy man from the back of beyond. He’s a translation from the rural economy, needed by the urban to ply his particular trade. His identification – his rural smock, a tie around his neck, loose white shirt, greying from the dust a yellow cap aslant upon his head. He checks his way is clear to start the downward thrust into the hole made for the sake of others but not for his kin – parents, sisters, brothers – The Hod Carrier not for his kin – parents, sisters, brothers does the red-bearded navvie plunge into the hole but for the nobility, the bourgeoisie and others. The Hodsman’s Heaven or Drink for Thirsty Souls is the title of the Puritan woman’s tract. He rudely brushes off the scourge of her tongue scours away the words, tries not to react. He’s like a dwarf entering a cave, his long flowing beard catches the light, then he’s gone to build the walls, forgets her warning words that in this darkened place are dead and done. He’ll continue with his drinking undeterred, the tract won’t save him, he’s no need of piety, our painter has charged him with immortality – The Pipe Smoker our painter has charged him with immortality though eclipsed in the shade of overhanging trees the Paddy, pipe in mouth, lures our sympathy as he’s travelled a long way from over the sea. Concentrating, gripping a larry in one hand he sweeps with the other. Is worthy of the powers of an English painter, who wants him to stand and sweep and pose for hour after hour. A trilby throws shadows on his half-hidden face a green hessian shirt marks him out from away, a stranger sleeping rough as is often the case but eager for the labour is this émigré. Far from his homeland in his work’s forward motion he’s an enigma of an indescribable emotion – The Ginger Haired Navvy he’s an enigma of an indescribable emotion, bearing a heavy bucket of water, to mix with quicklime – a mortar of a sticky volition he gives to the hod man and builders to fix the walls below ground for the supply of water. Red curly hair, a smile brightening his face the youngest of all causing roars of laughter as he cavorts around, teases the dogs, chases the ragamuffins, the women with the tracts, the man that sells ale, even the chickweed-seller who glares from under the brim of his hat. Women repulse him with gloves and umbrellas. Our painter respects the noble working men – he will want to depict them again and again. Epilogue Our painter respects the noble working men – will want to depict them again and again, believes that idleness is the devil’s chicanery but favours the navvies with great integrity– the painter does not consider the navvies to be too vulgar for his art for all to see. Their dirty, cement-spattered boots a token by the painter, the worker’s status is unspoken. Far from their homes in their work’s forward motion they are an enigma of an indescribable emotion. Limned, their portraits painted, their destiny is set down by our painter for posterity. The tracts won’t save them, they’ve no need of piety our painter has charged them with immortality. Wendy Holborow This poem won the Pre-Raphaelite Poetry Competition in 2016 and was published in the Pre-Raphaelite Review. Wendy Holborow, born in South Wales, lived in Greece for 14 years where she edited Poetry Greece. Her poetry has been published internationally and placed in competitions. She recently gained a Master’s in Creative Writing at Swansea University. Collections include: After the Silent Phone Call (Poetry Salzburg 2015) Work’s Forward Motion (2016) An Italian Afternoon (Indigo Dreams 2017) which was a Poetry Book Society Pamphlet Choice Winter 2017/18 and her most recent collection Janky Tuk Tuks (The High Window Press 2018) The Lovelorn Trees of Cozumel The Mayan Dryad, a distant cousin of the Saguaro Nymph, is an exemplar of adaptive evolution. A forest of photosynthetic sunbathers along the beaches of Cozumel take root in loamy homes and practice their supine stretches and come-hither eyerolls. Meanwhile, mainland Homo sapiens get SPFed and sunblistered. Like the Yucatecan Melipona, whose meanderings and sugar cravings gave us vanilla pods, the Mayan Dryad symbiotizes with the flora and fauna of the island: lonely crustaceans scuttling across the bottom of the bright blue Gulf; verdant chains of besotted kelp (Laminaria tantalus) that eternally reach for chlorophylled legs; boatsful of well oiled, libidinous tourists; and a somber sun that glowers over the shores of reproductive isolation. According to unpopular myth, Mayan Dryads are the wayward offspring of Hun Hunahpu, who showered all his affection on the Maize Sprites of Chiapas. The god's rationed attention fomented rebellion in his beachbound children, thus they don't grow crops, don't go to school, and spend their days surfing, while their nights are passed making angels out of anguish. Edwin Alanís-García Edwin Alanís-García is the author of the chapbook Galería (Ugly Duckling Presse, 2019). His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in The Acentos Review, The Kenyon Review, Periphery, and Tupelo Quarterly. He received an MFA in Creative Writing from New York University and is currently a graduate student in Philosophy of Religion at Harvard Divinity School. Portrait Let's run through it again. Complexion—geisha white. Cheeks—deep pink (too deep). Hands—closed petals in her lap. The young lady is sitting in ...call it an elm. Two blood-red horses share her limb. They're screamingly small and seem to be blind. Nothing will come of this, she muttered in Finnish. Don't worry, he whispered, apart from the pink all is utterly perfect. She looked aside. The sky wilted for an instant. Come my dear, we're nearly there. She lifted her eyes. The look was ancient. It pierced the canvas and went on forever. Scott Elder This poem first appeared in Nimrod International. Scott Elder’s poems have been appeared in numerous magazines including The New Welsh Review, Southword (forthcoming), Orbis, The Moth, Poetry Salzburg, Cyphers, Cake, Nimrod International, The Antigonish Review, The French Literary Review, Crannog and The Journal. He was a runner-up in the Troubadour International Poetry Prize 2016 and among the winners of The Guernsey International Poetry Competition 2018 and Southport Writer’s Circle Competition 2017. His work has been highly commended in the Bristol Poetry Prize 2018,Poetry on the Lake International Competition 2018, Buzzwords Poetry Competition 2018, the Segora Poetry Competition 2015 the Brian Dempsey Memorial Competition 2017, and shortlisted in both the Fish Poetry Prize 2017 and the Plough Prize 2016 and 2017. His debut pamphlet, 'Breaking Away' 2015 was published by Poetry Salzburg and a first collection 'Part of the Dark' 2017 was published by Dempsey & Windle. Poetry sites: https://www.scottelder.co.uk/ |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|