|

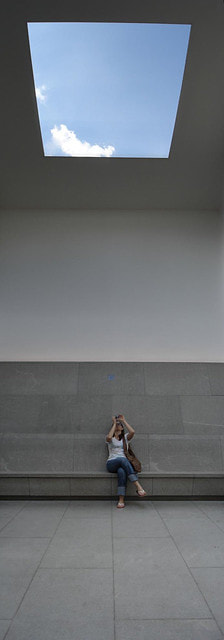

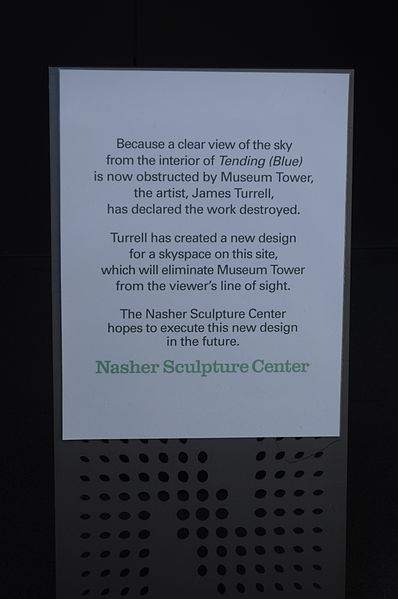

Tending (Blue) Don’t come to Paris, read the message from Henri, and Camille knew that he was no longer hers. Already in her hometown of Dallas for the transatlantic flight—having driven that morning from Waco, where she now lived—she chose to stay so that she could sleep in her childhood bed. The next morning, she sought out the sculpture garden, noting with relief that it was empty of patrons, save for a mother and toddler. Camille pulled her Hermès scarf, a gift from Henri, over her hair, ducked her head, and skulked to the back of the park, toward the dark granite structure of Turrell’s Tending (Blue). Its interior, she knew, was bathed in luminous white, a sensory deprivation tank pierced only by a square of blue above, the sky visible through a window in the ceiling. If no one else was inside, Camille could curl into a fetus in the artwork’s womb, peering from the corner of her eye at the eternal blueness above. But once at the entrance, she saw the doors chained shut; a posted sign declared, Because a clear view of the sky from the interior of Tending (Blue) is now obstructed by Museum Tower, the artist, James Turrell, has declared the work destroyed. Camille confronted the offending condominium—a glass and steel exclamation point newly punctuating the sky—then sank to a bench near Tending (Blue), now a sealed mausoleum. Hepworth’s neighbouring Monolith stood vigil, a tombstone. Beyond, Rodin’s Eve turned away, her right arm curved protectively around her body, her left hand shielding her face from Tending’s chained gates. Even Maillot’s La Nuit slumped, bereft, head buried in arms. Camille sat, irresolute, till strident cries from a blue jay and a splashing noise from a nearby pool pierced her consciousness. Even so, she ignored the noise, instead watching the mother at the garden’s opposite end as she guided her child up the exit stairs. The jay’s shrieks persisted, and now Camille noticed the distressed bird. Its offspring lay in the water just along the pool’s edge. She removed her scarf and scooped up the fledgling, its new feathers heavy with water. She returned to the bench, resting the bird in her lap. She cradled the juvenile jay in the warmth of her scarf, stroking the bird’s still body and murmuring to it softly, “Breathe, breathe.” All along, its mother worried loudly from branches above. Slowly, the baby jay revived. Between her palms, Camille felt its fragile frame—all heartbeat and skeleton—as it twitched. Opening its black eyes, the bird wriggled in surprise, then stilled itself in the scarf’s silk folds. Camille lowered the baby blue jay to the ground, backing away so its mother had wide berth to reclaim her chick. After chiding Camille soundly, mama coaxed baby into nearby ivy, where they disappeared. Camille turned back to Turrell’s locked doors and threaded her scarf amidst their chains, realizing she mourned the loss of Tending (Blue) more than that of Henri. Michelle Kraft Michelle Kraft is an art professor in Texas who has traveled extensively with university students, shuttling them throughout Texas, New Mexico, and Europe so that they can see firsthand the works they would otherwise only study in art history textbooks. While she has several scholarly publications, Michelle is relatively new to creative writing and is especially intrigued by the notion of how place informs experience and identity. Her work can be found in such journals as Visual Arts Research, Visual Culture & Gender, The Bowerbird and The Menteur.

0 Comments

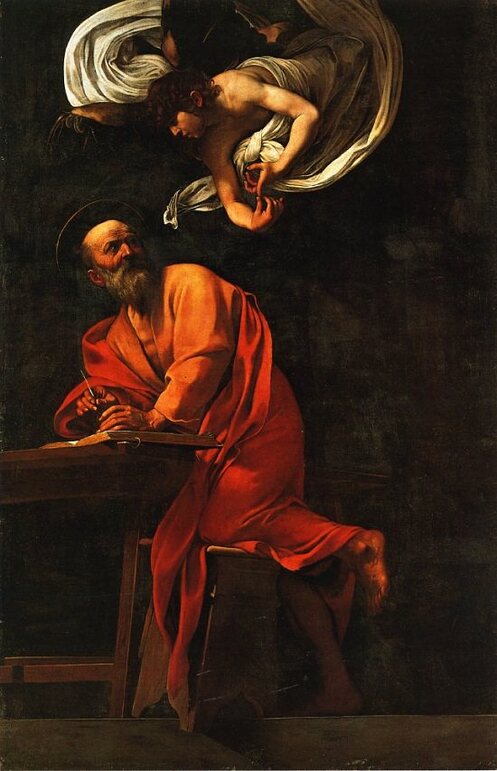

On Caravaggio’s The Inspiration of Saint Matthew Scowl as you may, you only grow more luminous, old man. The bright that covers you from long forehead to round shoulder, that drips beyond your knees and carnadines your toenails, is blood-bright. Above your victim-shaped heart, crimson with fear, there appears not a cherub fling-winged, but a real flesh child swaddled in winding cloths, knotted tight as a grace, coming to count and recount your sins on his forgiving plump fingers. He is whiter than a wax candle in the moonlight and rosy too with a rose you’ll draw from his peasant cheeks. He has flown from the darkest light world of all, come for you, to offer you a reprieve, a release, the turning over of a less livid leaf. Lillo Way Lillo Way's chapbook, Dubious Moon, winner of the Hudson Valley Writers Center’s Slapering Hol Chapbook Contest, was published in March 2018. Her poem, “Offering,” is the winner of the 2018 E.E. Cummings Award. Her work has appeared, or is forthcoming, in RHINO, Poet Lore, North American Review, New Letters, Tampa Review, Poetry East, Louisville Review, among others. Way has received grants from the NEA, NY State Council on the Arts, and the Geraldine R. Dodge Foundation for her choreographic work involving poetry. www.lilloway.com The Agrippine Sibyl siccabitur ut folium She sees what we can’t, her eyes grow dark and mirth leaves her. "We all will dry up. We all are horrible people. Filthy rags." The red of her robe nearly glowed, the color grew closer to crimson, grew closed. "Like a leaf in autumn." She puckers and blows. A wreath of twigs, of barbs, or thorns, and a wooden staff, one a coronet, one a divining tool, she says: "shrivel, wither, fade, wane we are each of us an arid leaf." She puckers her lips and blows. "This is your creation. What you’ve planted in soils can no longer forgive you. What you hold sacred is what you’ve destroyed." DeMisty D. Bellinger DeMisty D. Bellinger's writing has appeared in many places, including including The Rumpus, The Coil, and Necessary Fiction. She is a Pushcart nominated poet and an alumna fellow of Vermont Studio Center. Her short story “The Ballad of Frankie Baker” was selected for Best Small Fictions 2019. Rubbing Elbows, her chapbook, is available from Finishing Line Press. Learn more about DeMisty at demistybellinger.com. Pick up one of these cool journals here and The Ekphrastic Review gets a few bucks!

Art by Lorette C. Luzajic. Sylvia Plath and Philip Larkin. There are lots of other designs too, if you want to pen your ekphrastic notes with Wonder Woman or something urban and abstract! You Don’t Have To Like Braque I see how he treats you, leaves you dis jointed, un hinged Frowning, perhaps, though your white lips are cleft by planes, and It is hard to tell how you feel. You don’t have to like Braque Really, you don’t. I know What a mandolin looks like and It don’t look like that! I too find no joy in his browncollegeofdifficulty hisbroke nneckof perspec Tive, the knives and live fruit a throat swallowing nowhere. His love is cold thesis, a dialectic of grays, collapsing and folding, unfolding, confining you to his crumpled surfaces, bending your arms in impossible angles. He has placed you, parched, beside an undrinkable cup. “Why not that time in Kentucky?” I hear you say. “When we crouched in the tall grass, feeding the pink-tongued, butterscotch foal through the slats in the fence? Breathing the wet, green summer air that curled down from the white house, Sloped up to the blue sky, and you said that there were stars, Even now, behind that luminous screen. That was a pretty picture. Why not paint that?” I am here for you somewhere, a bright-eyed brown fish. I am Emergent, if you look for me behind those rusting pipes. I will Play this fractured instrument for you. For you, I have a simple cup that is not flat, that is not broken. We can fill it with cold water. We can drink. Edwin Rozic Edwin Rozic received his M.A. in English Literature from DePaul University. He teaches English to people who already speak English and lives in Chicago with his wife and son and a menagerie of furry and scaled beasts. His work has been published in McSweeney's, Glimmer Train, The Matador Review, SalonZine, and after hours. At the Movies with Monet (I, Claude Monet at the Tivoli) Naturally, we go to an art house. Monet remembers the first movies by the Lumière brothers. I assure him his art will be shown in full colour. It’s almost dark, nearly quiet fifteen minutes before the show. Few couples chat, preferring to sit side-by-side staring at their private mini-screens. No one notices Monet. He jiggles my seat, nervous without a smoke. Mon dieu! he says. Relax, you’ll be great, I promise. Pffew! he adds. I despise the opinions of the press and the so-called critics. I tell him he coined the motto of our times. A loud ringtone at the end of our aisle makes him jump. Sacré bleu! he explodes. When a woman’s voice over speaker phone tells us she’s had an upsetting day, Claude leaps to his feet. I tug hard on his famous tweed jacket, make him sit. We’re both relieved when Bergman’s Death appears on screen in his black cloak, warning us to turn off cell phones. A few minutes into the film, Claude pulls out his handkerchief. It’s him, all him in his own words, voiced by an actor who gradually shifts his voice to the crackle of an old man. I don’t sound that old, Claude grumbles. First we see the caricatures he was selling at age fifteen when he met Boudin. He watched the well-known painter at work, capturing the dazzling sunlight on women with parasols and frothy dresses enjoying a day at the beach. Magnifique, Claude whispers. Remembering the man who inspired him to paint outdoors for the rest of his life, he wipes his eyes. Alarie Tennille Alarie Tennille graduated from the University of Virginia in the first class admitting women. She’s now lived more than half her life in Kansas City, where she serves on the Emeritus Board of The Writers Place. Her latest poetry book, Waking on the Moon, contains many poems first published by The Ekphrastic Review. Please visit her at alariepoet.com.

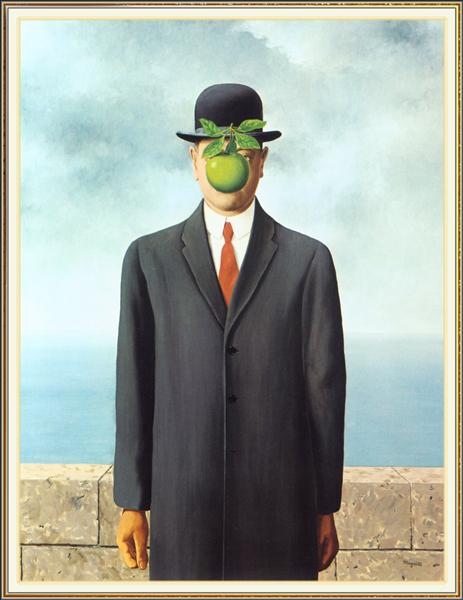

Apocalypse John the Revelator transcribes the language of an angel. His prose so elevated, so spidery and crabbed, that no one’s managed to distinguish whether it portends the fall of Rome or future end times, antiquated figures or some ensorcelled crystal ball which any fool could read into. In Bosch’s canvas, the usual menagerie of lepers, wraiths, skullduggery, lechers, bats, and beasts are nowhere to be seen for once—except in the corner lurks one bedeviled critter… An ordinary day, devoid of danger. John dips his pen and turns back to the angel. A ship, like history, burns upon the river. Will Cordeiro Will Cordeiro has work appearing or forthcoming in Best New Poets, The Cincinnati Review, Copper Nickel, DIAGRAM, Poetry Northwest, Sycamore Review, Tinderbox Poetry Journal, Threepenny Review, and elsewhere. He co-edits the small press Eggtooth Editions. He is grateful for a grant from the Arizona Commission on the Arts, a scholarship from Sewanee Writers’ Conference, and a Truman Capote Writer’s Fellowship, as well as residencies from ART 342, Blue Mountain Center, Ora Lerman Trust, Petrified Forest National Park, and Risley Residential College. He received his MFA and Ph.D. from Cornell University. Will currently lives in Guadalajara, Mexico. Recurring Dream: Visible But Hidden “Everything we see hides another thing, we always want to see what is hidden by what we see. There is an interest in that which is hidden and which the visible does not show us. This interest can take the form of a quite intense feeling, a sort of conflict, one might say, between the visible that is hidden and the visible that is present.” -Rene Magritte The flat blue sea meets a pale horizon. A turmoil of gray clouds moans at my back. I stand, impassive as the low wall behind me, bare hands rigid at my side. White shirt, red tie, black topcoat and, incongruously, a bowler hat, as if posing for Magritte. But where Magritte might have placed a luscious, leafy, sin-soaked apple, is a door: Thick timbered, rough-hewn. Hand-wrought hinges. Sturdy latch. Locked. Brain in nocturnal overcrank, my hand rises in slo-mo and knocks upon the door. A tentative tap, tap, tap. Then, balled into a fist, it pounds. Harder, louder. At last, an answer comes, through the clouds, beyond the sea: “Who’s there?” Brian Kates Brian Kates won a Pulitzer Prize and George Polk Award for editorial writing and a Daniel Pearl Award for investigative reporting as a reporter and editor at the New York Daily News. His book, The Murder of a Shopping Bag Lady, was a finalist for Mystery Writers of America’s Edgar Allan Poe Award in non-fiction. Recent poetry has appeared in Poem and Red River Review. He lives with his wife in a house in the woods in the lower Hudson Valley. Thomas Hart Benton Shows Me Where to Stand at the Edge of the Field Notice, first, the cut down ones, The broken shaft, supplicant head bent, Abundant bundles waving gold, The sun behind bakes repeating lines, Careful harvest cutting lines in the field. Notice, then, the green sprouting wild, Interruption weaving from the shadow. Then, the uneven heads of them. Then, the ominous lean of them. Even tight cuts of the shorn ones. Rows already down, and carried away. Consider, finally, breaking bread alone, Later, in the car or the museum café, The implication of bread. From what angle Might we see the man, just out of frame? & whose hands cut them down? & where The mill which churned them? The absent hand palming and hallow, kneading? Sara Judy Sara Judy is from the prairie. She is currently an English PhD and poetry MFA student at the University of Notre Dame, where she studies twentieth and twenty-first century poetry and poetics. Her creative work has recently appeared in Proximity Magazine, The Midwest Review, and Bluestem. Sara also serves as an assistant book editor for Religion & Literature, and as an editorial assistant for the Notre Dame Review. Ekphrastic Writing Challenge: Mark Rothko

Join us for biweekly ekphrastic writing challenges. See why so many writers are hooked on ekphrastic! We feature some of the most accomplished influential poets writing today, and we also welcome emerging or first time writers and those who simply want to experience art in a deeper way or try something creative. The prompt this time is Untitled, by Mark Rothko. Deadline is August 9, 2019. The Rules 1. Use this visual art prompt as a springboard for your writing. It can be a poem or short prose (fiction or nonfiction.) You can research the artwork or artist and use your discoveries to fuel your writing, or you can let the image alone provoke your imagination. 2. Write as many poems and stories as you like. Send only your best works or final draft, not everything. Please copy and paste your submission into the body of the email, even if you include an attachment such as Word or PDF. 3. Have fun. 4. USE THIS EMAIL ONLY. Send your work to [email protected]. Challenge submissions sent to the other inboxes will most likely be lost as those are read in chronological order of receipt, weeks or longer behind, and are not seen at all by guest editors. They will be discarded. Sorry. 5.Include MARK ROTHKO WRITING CHALLENGE in the subject line in all caps please. 6. Include your name and a brief bio. If you do not include your bio, it will not be included with your work, if accepted. Even if you have already written for The Ekphrastic Review or submitted other works and your bio is "on file" you must include it in your challenge submission. Do not send it after acceptance or later; it will not be added to your poem. Guest editors may not be familiar with your bio or have access to archives. We are sorry about these technicalities, but have found that following up, requesting, adding, and changing later takes too much time and is very confusing. 7. Late submissions will be discarded. Sorry. 8. Deadline is midnight, August 9, 2019. 9. Please do not send revisions, corrections, or changes to your poetry or your biography after the fact. If it's not ready yet, hang on to it until it is. 10. Selected submissions will be published together, with the prompt, one week after the deadline. 11. Rinse and repeat with upcoming ekphrastic writing challenges! |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|