|

The Ascension As he said this, he was lifted up while they looked on, and a cloud took him from their sight... The Acts of the Apostles: 1:9 Into ashen sky I rise upward bright as sunshine dazzling from afar; scarred body of flesh evanesces, becoming sparking mist illuminating cloud cover. My mystical farewell overwhelms minds of devoted acolytes-- faithful followers deciphering their heart’s ineffable stirrings. A phantasmagoric metaphysical shift, witnessed in awe by truth seekers unable to fully comprehend my final transformation from man to eternal spirit. Davidson Garrett Davidson Garrett is a native of Louisiana and lives in New York City. He trained for the theatre at The American Academy of Dramatic Arts and graduated from The City College of New York. He is a member of Actors Equity and SAG/AFTRA and worked in television, film, and theatre for many years. His poetry has been published in The New York Times, The Episcopal New Yorker, Sensations Magazine, First Literary Review East, Xavier Review from New Orleans, and in Podium: the online literary journal of the 92nd Street Y. Davidson is the author of the poetry collection, King Lear of the Taxi, and the chapbook, What Happened To The Man Who Taught Me Beowulf? Recent work includes poems in the anthology, Stonewall's Legacy, published by Local Gems Press. He was the curator for the Boog City Poets Theater in 2016, and 2018, in New York's East Village.

4 Comments

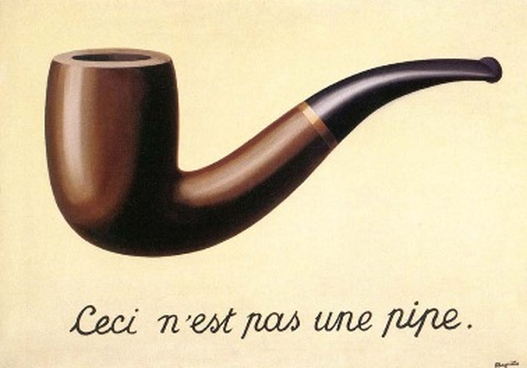

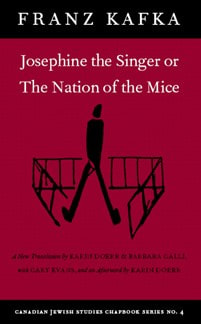

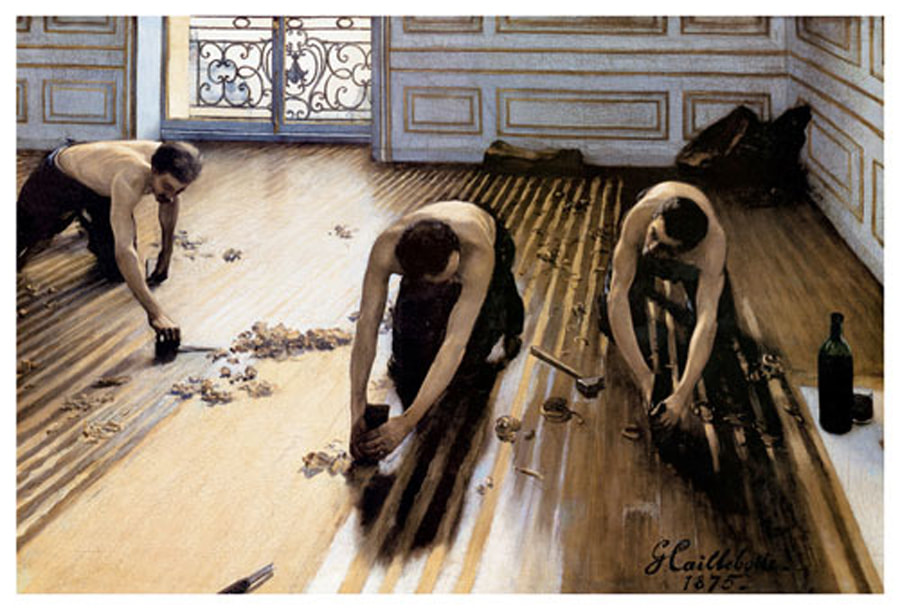

Scavengers It's one thing to mention the exploding population of dead whitetail deer along the shoulders of our Interstate highways, because who doesn't mind seeing a gentle creature like a whitetail---even a dead one, whose crumpled or swollen but still delicate body provides an opportunity to reflect on our common mortality with tenderness and sincerity but without undue regret, assuming, of course, that you didn't wreck your car and were not the guilty driver. But what of the crushed possum with its hairless tail and toothy grin? And what about those turkey vultures who lately seem to be everywhere, soaring in ever-narrowing circles or else spreading their coarse-feathered wings to dry as they perch on a cell tower. After my father died, and they were about to close his coffin, my mother stepped forward at the very last moment to tuck a fifty-dollar bill into the pocket of his shirt. "Because you were always so worried about money," she said, "but everything will be okay now." And frankly, it took an effort of will to stop myself from pulling that fifty bucks out again because I was, after all, his son, but I held myself back, mainly by thinking about the comforting if unlikelypossibility of some sort of afterlife and the reassuring message provided by grave goods, by those elaborate gold masks entombed with Egyptian pharaohs, or by clay jars of spear points buried alongside Cheyenne warriors, or by dried flower petals in Neanderthal mounds. As a poet who teaches Freshman Composition for a living, I occasionally consider gleaning a misplaced or inexact but nevertheless highly-original turn of phrase from an essay that one of my semi-illiterate students has written, but so far I've managed to resist the impulse to plagiarize although each time I fail to do so means those particular words will never get to live again. Once, at eighteen, I brought a new girlfriend home to meet my family, and she walked into a scene that looked like something like the ugliness and squalor that Van Gogh had depicted in his painting, The Potato Eaters, where the weary faces of the peasants clustered around a table tell us everything we need to know about their poverty and suffering. In our kitchen, a rusty old refrigerator had been wired to a fixture in the ceiling where a single bare bulb hung down, and the holes in the crumbling plaster were cast into high relief. fingering the pennies he'd saved for years in a pickle jar until they could be counted, stacked, and rolled into paper cones. It was almost too much-- I couldn't have staged it better, because I could somehow feel my girlfriend recoil at the grimness and grit, which was, I realized, exactly why I'd brought her home. This is who I am, I'd wanted to tell her. This is what you're in for. But memory has a way of playing cruel tricks because I probably wasn't half that self-aware back then, and the life we'd go on to lead together wouldn't be nearly as bad as that. For these were simply images I'd later scavenge and hoard against a deathless future, the ridiculous possibility of artistic immortality I once imagined I'd get to live. Michael Colonnese Michael Colonnese lives and works in Fayetteville, NC, where he directs the Creative Writing Program at Methodist University and serves as the managing editor of Longleaf Press. He is the author of a mystery novel, Sex and Death, I Suppose, and of two poetry collections, Temporary Agency and Double Feature. Josephine This is not a pipe. Strunk & White ain’t right about nuthin’. Tell, not show-- My people of the book, of the birdsong, Not the image graven on the silver scream. You want a fetish But my Rose is not a rose. She’s my sister Or the color of your glasses When you think these matter Or the acronym for Renal Oncology Service Enterprises (Where my brother went). This is not a pipe. It is not two orange butterflies—Dryas Heliconian—tangoing in the breeze on Nine Mile Run, the sun scorching their beaten wings But my words, the pages in flames. Our torah burning The Words say: “I am big. It’s the speakers who got small. We’re not an image, but ‘Mama.’ ‘Dada.’” My hands reaching for the unseen, Digits I don’t even know yet but strange lumpy beings. And so begins, Josephine: “The sun through dappled leaves, yellow on green. What words the eyes speak between,” Yet you say no, no, no, no, no! Nothing but things And I say no, nononono I am Not mere taxonomy. You can’t just “write me off” with your zeroes and ones In your virtual ledger of pretty things. I am the still small voice that sings, Josephine. There is no like. A wasp’s nest is not like a grey shrunken head with wisps of dank hair on its skull, its mouth shriveled to a terrible tiny O—note that letter O--where the bugs crawl out. It is not hanging from a branch over us like an innocent man who wants revenge on the absence of language. I am Aleph with my arms raised in victory or despair. I am Bet—not on the ponies—but closed on three sides The first letter of the Pentateuch, the house of creation. I am my brother metastasized, blind to your world of things, gasping “Why mommy?” as he flatlined, Not the squirrel whirling a nut in its furtive paws, Or the deer on Tranquility Trail munching grassy-mouthfuls with that slow slanted chew of ruminants. Jo-el- Josephine. If your heart listens you can hear: I am not a thing. I am the still small voice that sings. I am the still small voice that sings. iamthestillsmallvoicethatsings. Lewis Braham "The inspirations for this poem are Rene Magritte's The Treachery of Images, Kafka's "Josephine the Singer," Kings 19:12 and the death of my brother Joel." Lewis Braham's writing has appeared in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, Barron’s, Tuck, the Wall Street Journal, Reuter’s, Bloomberg and BusinessWeek.

Outside the Walls I run down the path, looking for an opening, but the red portal is closed, and the steel doors are bolted. I could climb the ladder into the pink sky, but then I may be seen by a drone or sniper. I run the circumference, hoping for access, hoping to find a sentry who will take me to you. I don't know why I am looking for you. I don't know what I will say to you. Ed Gold Ed Gold is a Charleston, SC poet who has published a chapbook, Owl, and over seventy poems in various journals, including the Cimarron Review, Kansas Quarterly, and Rat's Ass Review. One of his favourite gigs today is running the Skylark Contest for the Poetry Society of South Carolina. He discovered ekphrastic writing in this artist's studio, where he wrote this poem.

Whistler Hits the Motherlode Well before Motherwell After painting The White Girl, the artist began calling his works symphonies, arrangements, harmonies, nocturnes: As music is the poetry of sound, so is painting the poetry of sight. Focused on tone and surface, he laid down a touch-pad for particular textures, dry-brushed the front of his mistress’s dress to let the white underneath show through and render the material gauzy. Her red hair offered perfect contrast to the subtly of the background. Bear-skin rug, blue of the carpet and color of the flowers all offset the woman in white. Her impassive face and limp arms complemented white on white, highlighting color harmony as his only real subject. Is Whistler just whistling Dixie? This is not the painting we created: Start with a full-scale society portrait that’s a Victorian lesson in morality. White tones and the lily imply purity, but the lily is broken and Joanna’s dress and disheveled hair whisper impropriety. Her chastity suppresses the fierce bear whose head is thrust menacingly toward us. Portrait of a bride on the morning after, Lady Macbeth sleepwalking, or the Virgin Mary come to save us from eternal explication. Lee Marc Stein Lee Marc Stein lives in East Setauket, New York. His poems have appeared in Blast Furnace, Blue Lake Review, Message in a Bottle, Miller’s Pond Poetry, Slow Trains Journal, Still Crazy, Subliminal Interiors, Write Place at the Write Time and The Write Room. His first book of poetry, Whispers in the Galleries, features ekphrastic poems. Lee has had short stories published in Bartleby Snopes, nicollsroad, Write Place at the Write Time, and Down in the Dirt. He led workshops at Stony Brook University’s Lifelong Learning program on modern masters of the novel. A poor golfer, he excels at creating excuses for not playing well. Colours after Nuno Júdice If you wish to paint the colour of my heart, start with a palette of your smiles, and soft-brush my face with the marigold sun shining on yours; the meadow green of your eyes for mine. Your lambent blue whispers in my ear burn azure as the sky. But this only colors the blood in my veins. I breathe you in, inhale the scarlet of passion. I quiver incarnadine. Our lips blend together, grisailled with the charcoal of our shadows. Pencil each stroke intensely purple, just as our moans. You will then see the colour of my heart melt in your hands. John C. Mannone This poem was inspired by the painting shown, and by a poem by Nuno Judice. Receita Para Fazer Azul, by Nuno Júdice (Portugal). 1994. (Translated by Richard Zenith.) John C. Mannone has work in/forthcoming in Adanna, Anacua, Number One, Artemis, Poetry South, and others. He won a Jean Ritchie Fellowship in Appalachian literature (2017) and served as the celebrity judge for the National Federation of State Poetry Societies (2018). He’s a retired professor of physics living near Knoxville, TN. http://jcmannone.wordpress.com Join us for biweekly ekphrastic writing challenges. See why so many writers are hooked on ekphrastic! We feature some of the most accomplished influential poets writing today, and we also welcome emerging or first time writers and those who simply want to experience art in a deeper way or try something creative.

The prompt this time is Seascape-Jetty, by Henry Ossawa Tanner. Deadline is January 10 2020. The Rules 1. Use this visual art prompt as a springboard for your writing. It can be a poem or short prose (fiction or nonfiction.) You can research the artwork or artist and use your discoveries to fuel your writing, or you can let the image alone provoke your imagination. 2. Write as many poems and stories as you like. Send only your best works or final draft, not everything. (Please note, experimental formats are difficult to publish online. We will consider them but they present technical difficulties with web software that may not be easily resolved.) Please copy and paste your submission into the body of the email, even if you include an attachment such as Word or PDF. 3. Have fun. 4. USE THIS EMAIL ONLY. Send your work to [email protected]. Challenge submissions sent to the other inboxes will most likely be lost as those are read in chronological order of receipt, weeks or longer behind, and are not seen at all by guest editors. They will be discarded. Sorry. 5.Include TANNER WRITING CHALLENGE in the subject line in all caps please. 6. Include your name and a brief bio. If you do not include your bio, it will not be included with your work, if accepted. Even if you have already written for The Ekphrastic Review or submitted other works and your bio is "on file" you must include it in your challenge submission. Do not send it after acceptance or later; it will not be added to your poem. Guest editors may not be familiar with your bio or have access to archives. We are sorry about these technicalities, but have found that following up, requesting, adding, and changing later takes too much time and is very confusing. 7. Late submissions will be discarded. Sorry. 8. Deadline is midnight, January 10, 2020. 9. Please do not send revisions, corrections, or changes to your poetry or your biography after the fact. If it's not ready yet, hang on to it until it is. 10. Selected submissions will be published together, with the prompt, one week after the deadline. 11. Rinse and repeat with upcoming ekphrastic writing challenges! Against the Grain So, Charlotte: finally, I see the completed painting, and I wish you could see it with me. It is larger than I thought, yet looks small in this mausoleum of a building. The doorman’s look of disgust made plain that The Louvre is not for the likes of me. You would hate the cold inside, too, Charlotte, just as you hated winter. The painting is clear as one of these modern-day photographs, in the same grey-brown tones. If only you had lived to see it, my love. Memories weigh my eyes down so heavy I can hardly look. Then, like a shy lover, I can't resist. Look! Look how the light fell through the window and stroked the floorboards. I feel the heat of that summer all over again. Look at the line of my muscles. You always told me I was strong. Now I understand. 'Robert - the light will illuminate the curve of your shoulders - along here,' Monsieur explained, running his finger along my back. I said nothing. How could I speak when it was all I could do not to shiver? The old pain rises in my chest. It’s jealousy – of the love that Monsieur showed to you, and jealousy that I must share this painting with those other men. I am in the background. ‘The viewer’s eye will be drawn to you because of the Golden Section,’ Monsieur told me. Whatever that meant. At least he chose to show more of my body. Perhaps I meant something to him. We three were on our hands and knees, working. Those two whispered, heads together, and I was never a part of it. Except we didn’t work. Really, we posed while Monsieur sketched us. Floor scrapers. Humble workmen, and he painted our picture. We were all stripped to the waist, and Charlotte, it’s my body you see the best in Monsieur’s painting. The heat that summer was intense. Sweat pooled between our shoulder-blades, in the small of our backs, it ran down our faces and dripped from our noses. We wiped them on our shirtsleeves until Pierre swore and stripped off his shirt. We copied him. Only the poor, or the stupid, worked that hot August afternoon in Paris. The heavy air muffled the sound of a carriage from the boulevard outside. Wood-dust hung in shafts of sunlight. It coated our sticky bodies, the insides of our mouths and noses, and blanketed the wooden floor in a thick layer, swept into uneven piles by the shuffle of our trouser knees. We worked in silent rhythm, a soft hissing outbreath escaping from our scrapers as the wood spiralled into curls. Jean-Luc filed the blades of our planes to a tiny burred hook on one side – he had skill in that - so we could shave the thinnest of slivers from the wooden floor. We were not aware of Monsieur watching us, leaning in the door frame. 'Would you care for wine?' His voice was the caress of a brush on canvas. Pierre jumped to his feet and grabbed his shirt. 'No, no. Not on my account - it's too hot. Keep your shirts off.' Monsieur brought us a bottle and three glasses himself. We sipped a little, but, with his eyes still on us, we returned to work, crawling up and down the floorboards like black beetles, along the grain, our scrapers rasping the floor. His followed our bodies like wood dust stuck to our sweat, yet I could not look at him. I wanted him to watch me, but did not understand why. I scratched at this new thought in my mind: scraped the layers away, until I dug against the grain into the floorboard with my scraper and I knew I must concentrate harder. 'Call me Gustave,' said Monsieur. As if I, or Jean-Luc, or Pierre, could ever call him anything other than Monsieur. 'I am an artist,' he said, 'and this room is my studio.' This room - this huge room - bigger than all our rooms put together with the neighbours, Charlotte! I thought an artist would have wild hair and beard, and be spattered with paint. This man was neat and small with a narrow, unexceptional face and he wore his grizzled hair cropped short. ‘Whoever heard of working men having their picture painted?’ Pierre grunted, later, after Monsieur asked to paint us. ‘He’s paying us well,’ said Jean-Luc. ‘Are you in or out, Robert?’ ‘In,’ I said, my tongue thick. I wanted so much to be watched by this artist, this Gustave. ‘Me and Charlotte need extra money,’ I added. ‘I’d give Charlotte extra’ said Pierre, and I laughed so he did not despise me, but I felt sickened by his talk. And, next morning, when we arrived in the Rue Meromesnil apartment, a fresh bottle of wine and three glasses waited on the tray. Monsieur arrived too, and stood in the doorway watching. My heart hammered in my ears. I lowered my eyes and stayed silent of course. Such a fire burnt inside me that a single spark could have caused a blaze in the wood shavings. Monsieur scrutinised us from behind an easel set by the door. We crept up and down between the lines like caged animals. I would have roared for him. He came into the room and reached towards me. ‘Stretch out your right arm, Robert, if you please,’ he said, and smiled. His smile was so large, it was like the sun shone out from his face. ‘Now press down… to define the muscle.’ He took my hand and moved it over the wood. I shivered, despite the heat, despite my best intentions. ‘Of course, you’re tiring,’ said Monsieur, crouching behind me and reaching his arm across my back. ‘You’re not used to modelling for an artist. Breathe easy. Now roll your arm out from the wrist a little. Take more weight onto your left arm. Now keep still.’ The next day Monsieur asked me to stay behind after the others left. My longing blazed on my cheeks. Monsieur positioned me on the floor, on hands and knees like in the painting. His hand lingered on the nape of my neck. 'Don't move,' he said, breath warm on my ear. He moved away to his easel and seconds passed, maybe minutes, maybe hours. Pins and needles prickled in my hands and arms. Monsieur had finished, he said. I was frozen in the heat. Stuck, like an old man. He helped me to my feet, his hands either side of my body. I longed for him to put his arms around me, and burnt with shame that I should crave such a thing. He held me firm by my shoulders, smiled his big smile and I fell into the intense blue of his eyes. 'You are perhaps dizzy, Robert? Sit here awhile.' He led me to a chair and handed me my shirt. I could barely button it up. Sitting beside me, he took my hands. I concentrated on keeping still, on keeping my breathing steady. He lifted each of my fingers in turn - to get the details right, he said. My hands were grimy and brown, calloused and larger than his, with ugly chewed nails. I was felt ashamed of my workman’s hands. Monsieur asked where I lived, said he’d have someone bring me my payment. That evening, Charlotte, though I never said, I was not surprised when he delivered my money himself. Neither was I surprised that you read my mind and invited him in for wine, though you had never asked in my friends before. We three sat at our rough wooden table, in our tiny room, Monsieur with the one good glass and you and I with mismatched ones. We turned the chipped edges away from him, without need for words. He was polite and kind, putting us at ease with his wide smile and sparkling eyes. We both drank our wine too quickly, but Monsieur hardly touched his – too coarse, I suppose. He talked, with wit and gentleness, looking first at me, then at you, Charlotte, drawing us in to him with his words, hypnotising us. I dragged my eyes away from him and looked at you. You glittered like sun on running water. You leant forward, chin on hands, elbows on the table. Your eyes were locked onto his, and you were imprisoned in a mutual smile. Your brown curls waterfall down your shoulders and candlelight danced in your dark eyes. Your delicate white hand drifted up to your mouth, as if your happiness was more than could be contained in your face and it spilled over. Monsieur leant on his elbow and smiled too, that smile which transformed his face into handsomeness, an upturned curve such as a child might draw. And you, Charlotte, you basked in its warmth, your face tipped up the way you lifted your face to the sunshine after winter. And then, it came to me with painful certainty, that for you both, I was not present. You had not read my mind, after all. It came to me that Monsieur’s big smile was for you alone. That this entrancing murmur was for you, he had already forgotten me. I gulped the dregs and banged my glass onto the table, but neither of you noticed. In that moment, I lost what might have been for the first time, and the shadow of that loss resides in me still. Monsieur never painted you, Charlotte. Always me. I learned never to ask where you’d been and when you were coming home. You were still my best friend; my wife, the only one who understood how my truest feelings went against the grain. I comforted you at his passing, and we cared for each other all those years after he was gone. And now you’re gone too, Charlotte, and all that’s left of we three is hidden in this painting, in this cold room. And outside, a fresh layer of snow hides the icy boulevard. Helen Chambers Helen Chambers has been published widely, including in the Citron Review, Spelk, The Drabble, and Potato Soup Journal. https://helenchamberswriter.wordpress.com/writing/ Young Gloria Swanson as the Lion's Bride Mister DeMille is flabbergasted by this gutty nobody with her damn-your-eyes blue stare. She insists she wants to be in the Lion Pit scene with a real lion. Demands it. Says her pride as an artiste is involved. It's her time, that time when starlets cringe back and stars stride forth. He's afraid the beast will fall on her like she's made out of ham. He'd like to strangle that milky neck, and says so, but all the while his movie gut fiercely craves that lovely freak face with its goddess bones, which he knows could be successfully shot from any angle. His life will never meet such a face again. Finally she batters him down. She's adorned, perfumed, clad in dancing pants and basic breastplates. He directs with a revolver in his hand. Shooting begins. She creeps into the musky pit, turns, she and the brute lock eyes. Action commences so terrifying that DeMille later tells intimates he almost defaced his pearly jodphurs. After a complex and seductive pursuit, monstrous claws weaving after trembling brocades, Swanson swoons to the rock floor. The lion puts his heavy paw on her naked back and hotly breathes up and down her spine. Sixty years later she would remember how every hair on her body stood up. The trainer lashes the beast away with his whip. One take. A star shakes free from the red choke of mane. Two weeks later DeMille and Swanson learn the lion has flayed his trainer to the bone. Margaret Benbow The poem was originally published in The Georgia Review. Margaret Benbow is a poet and fiction writer whose poems and stories have been widely published. A collection of poems, Stalking Joy, won the Walt McDonald First Book Award. A collection of fiction, Boy Into Panther and Other Stories, won the Many Voices Project Award and was published in 2018 by New Rivers Press. Supplication The specter blazed and found her at the well. Blinded, she fled, darted down an alley, stumbled, water sloshing from the urn. The angel overtook her, uttered sweet verse into her small, curvature of ear; and Mary grasped what he meant to say, nodded, and returned to the well, anew. O specter, muse, come dazzle me with other-worldly light. Trip me, knock me down, dump my pan of dishwater words; open my fleshy lobes to your whisper, pure and piercing as a flute, so that I might hear and comprehend your dispatch, and begin again. Teresa H. Janssen This poem first appeared at Cathexis Northwest Press. Teresa H. Janssen has an M.A. in Linguistics from the University of Washington. She was a finalist in Bellingham Review's Annie Dillard creative nonfiction contest and her essay, 'My Fifth Sense', was named a notable American essay for 2018 (Solnit & Atwan). Her prose and poetry have appeared in Anchor Magazine, Zyzzyva, Tiferet, Lunch Ticket, Dos Gatos Press and Cathexis Northwest Press, among other publications. She can be found online at: www.teresahjanssen.com. Teresa is presently living in Kampala, Uganda. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|