|

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island

In Sunday scene, Seurat with pointillism Created through illusion new impressions; Bent the rules of light as sure as prism, Redefining Art by pure expression. Contemplate the waters sheen eternal. Glimpse a sky obscured, made hard to find. Wonder at attire to our eyes formal, Worn with leisure uppermost in mind. How the shadows render definition To black umbrella, crinoline and skirt! See the skipping girl in fixed position, Monkey in the foreground, pale, inert. Note the rowers bent in their exertion, A cast of people, young, old, rich, and poor; Parasol and picnic in conjunction, Boatman cradling pipe in burly paw. Ponder leaf convergence from a distance, Precisely as Seurat intends you do. Wonder at tree-trunk’s stark insistence Your eyes avert to details meant to view. Why is this a work for admiration, Extending even to the dotted frame? I proffer that purposed pixelation Mimics Life’s perfection much the same. For what are we if not a mass of dots Comprised of DNA uniquely mixed By Master hand with absolutely lots Of palette permutations, never fixed? David Watt David Watt is a poet residing in Canberra, Australia. His poetry has been published on The Society of Classical Poets website, within various themed collections of poetry and prose, and The Empath magazine. He enjoys responding to diverse topics, and always brings focus to the beauty of life.

0 Comments

José of Lisbon In the small hours of the first Leap Day in the Gregorian calendar, José of Lisbon was born. He opened his eyes against the smoky light of the candle, smelled the fish rotting under the piers, and heard the grating mews of the stars moving in the black sky. José cried, hiccupped, and went straight to his mother’s breast. But even that first night the path of stars never let him rest. José’s mother used her breasts to mute the clacks and squeals of the stars for José, but still the baby cried in frustration. By the age of five, José cringed at sunset; the North Star twinkled like a rusted gate creaking back and forth. Never mind the cacophony of screeching and caterwauling of the lesser stars. At night he would fill his ears with straw or wool and bound his head with a cloth. His mother would recite the prayers every good Catholic knew, and José knelt alongside her, hoping God would listen to their pleas. On Sundays they walked to the cathedral and knelt before the statue of Mary. “Please, God,” José prayed. “Let the sun remain in the sky if not for the rest of my days, at least for one. One night’s peace is all I ask for.” When José came of age, he left home to claim his fortune. He walked up the gangplank of a ship bound for the Americas, bowed once to his faithful mother, and prayed the restless sea would be the solution. Surely the lull of the swells, the fury of storms, would drown-out the stars. He sailed for five years and became a rich man; his skin became swarthy and salt-ridden; he grew a beard and tied his hair back with a leather thong. Many men feared his strength and prowess on the ship and in far-away lands. The gold in the ship’s hull gave him security but no peace. At night he prayed like a child in his grand chambers. “Please, God. If you won’t halt the sunset, please stop-up my ears against the stars.” On the seventh Leap Day in José’s life, a rogue wave swept across the Indian Ocean and dashed his ship to pieces. Another wave dumped him on a lonely shore at dawn. He walked inland until he found a group of pilgrims on their way to Mecca. A very old man, with a myriad of wrinkles and yellow fingernails listened to his tales of woe. “Your fortune may be lost,” the ancient said, “but no longer will the stars be an affliction.” Without ceremony the man tapped José on the forehead twice with the knob of his walking staff. “May Allah always be with you,” he proclaimed in a voice of aged authority. “Am I cured?” José asked and took the man’s gnarled hand in gratitude. “No, my son.” The man looked up at José with a toothless grin. “But now, you have two gods to complain to.” Sarah Kilgallon This short story was first published as a chapbook by the Harvard Bookstore. The story was inspired by a character in a story by Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Click here to read "A Very Old Man With Enormous Wings." The painting was selected by The Ekphrastic Review and was not the source of inspiration for the story. Sarah Kilgallon is a Boston writer who studied at Lesley University and the University of Massachusetts. She is also involved in initiatives to help refugees and immigrants. Empyreal Rondeau In ghostly skies a stellar glow from erstwhile stars of long ago that shone with splendor ere they died, perchance were wished on starry-eyed, still haunts in heavens’ spectral show. We gaze with wonder from below, amidst our scurries to and fro, at panoramas mythified in ghostly skies. The winds of fame and fortune blow with sound and fury fiercely, though our life be ebbing like the tide; for death o’er all shall yet preside, unfathomed as the cosmic flow in ghostly skies… Harley White This poem was first published by the Astro Poetry Blog of Astronomers Without Borders. Harley White is a born word-lover and has written works dealing in fairy tales, musical theater, many genres of poetry, and awakenings, as well as a book titled The Autobiography of a Granada Cat – As told to Harley White. For many years, she has been a follower of the Buddhism of Nichiren Daishonin and its practice of Nam Myoho Renge Kyo. http://harleywhite.awardspace.com/ Haywain

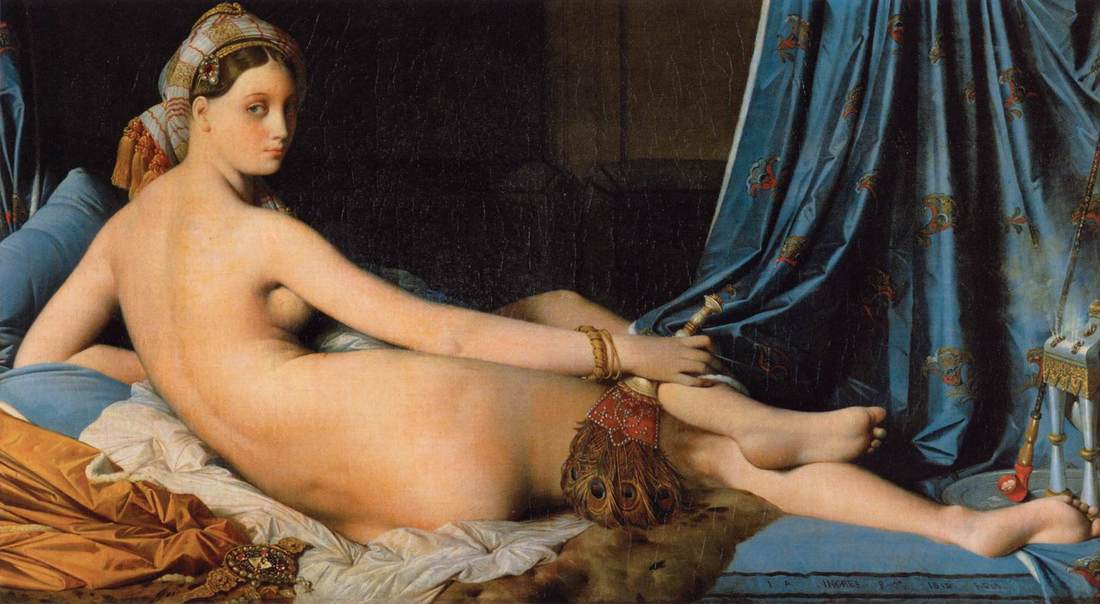

Her milkman Grandad often takes her, his horse, cart and churns on his rounds gifts her a small pony trap and horse. Older she hangs a copy of "The Haywain" above a dark brown oak dining table with its curved back oak chairs lit by white light French windows on to a grey concrete slabbed patio. She knows the smell of worked horse, creak of cart and water's rhythm, much like milk slap and hooves on cobbles. Paul Brookes Paul Brookes was shop assistant, security guard, postman, admin. assistant, lecturer, poetry performer, with "Rats for Love", his work included in "Rats for Love: The Book", Bristol Broadsides, 1990. First chapbook was "The Fabulous Invention Of Barnsley", Dearne Community Arts, 1993. Read his work on BBC Radio Bristol, had a creative writing workshop for sixth formers broadcast on BBC Radio Five Live. Recently published in Clear Poetry, Nixes Mate, Live Nude Poems, The Bezine, The Bees Are Dead and others. Forthcoming this summer is an illustrated chapbook called "The Spermbot Blues" published by OpPRESS, and tentatively in autumn "The Headpoke" illustrated chapbook published by Alien Buddha Press. Sound Madness --After Seeing Ingres’ "La Grande Odalisque" Online I love how O starts low in the belly like Om, arises in the throat with da, and eases past my grinning teeth with ee. These sounds to me are succulent soma, physical drugs, so Odalisque can’t trick in her light manner, staring in the raw all nil. She must lay in sounds we can lick, sounds we can kiss with open mouth. Her hue must not convey or feign in pixel talk, but shout at dilettantes who dare subdue her lines. Her peacock eye, the one that’s blind at night, must not elude one part of you, art lover; it must roil the blood in kind and compel the sound madness of your mind. Gregory Palmerino Gregory Palmerino’s essays and poems have appeared in Explicator, Teaching English in the Two-Year College, College English, Amaze: The Cinquain Journal, International Poetry Review, The Literary Hatchet, The Courtland Review, Shot Glass Journal, The Lyric, the fib review, The Road Not Taken, Autumn Sky Poetry Daily, The Ekphrastic Review, Lighten Up Online, The NewVerse.News and The Asses of Parnassus. He teaches writing at Manchester Community College and writes poetry in Connecticut’s Quiet Corner, where he lives with his wife and three children. La Part du Feu

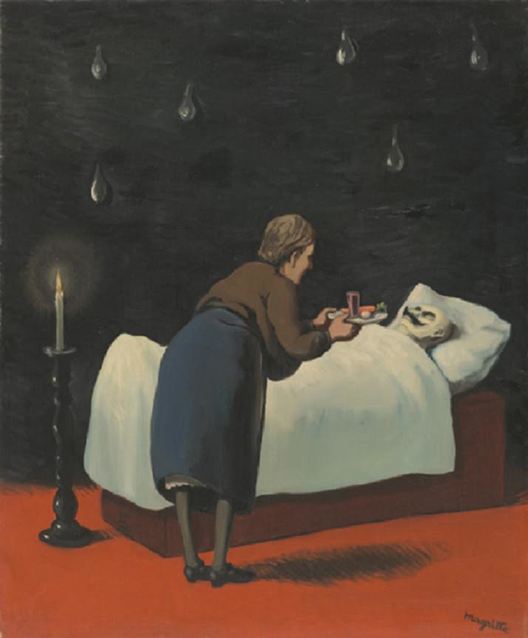

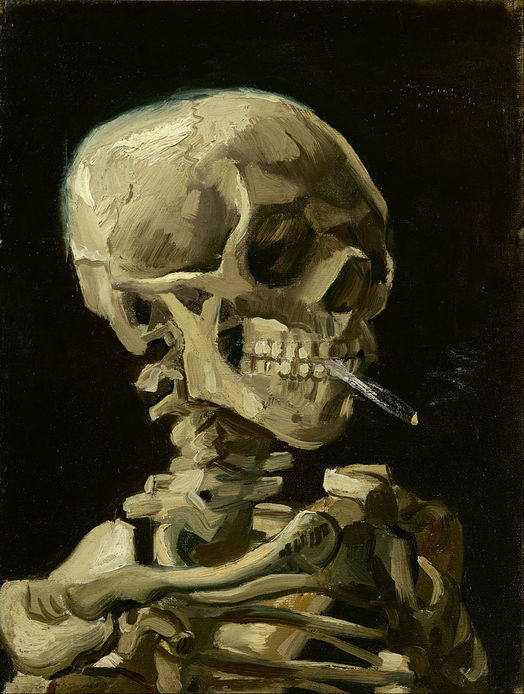

In no particular order, the clues are a carrot, an egg, & a glass of some un- known liquid, vin or vinegar, it's not clear. In no particular order, raindrops keep falling from the ceil- ing, a candle halos but provides no light — though an external light source casts a compressed shadow of the housekeeper on to the carpet. In no part- icular order, Hercule Poirot, as played by David Suchet —who isn't — is dead, the housekeeper main- tains not a vigil but a pretense of life within the room, hard to tell if the egg is hard-boiled, easy to see the detective isn't. Mark Young This poem is from a dedicated website, mark young's Series Magritte : https://seriesmagritte.blogspot.com/ Mark Young lives in a small town in North Queensland in Australia, & has been publishing poetry for almost sixty years. He is the author of over forty books, primarily text poetry but also including speculative fiction, vispo, & art history. His work has been widely anthologized, & his essays & poetry translated into a number of languages. His most recent books are Ley Lines & bricolage, both from gradient books of Finland, The Chorus of the Sphinxes, from Moria Books in Chicago, & some more strange meteorites, from Meritage & i.e. Press, California / New York. Earlier poems from the series have been collected in three print collections — from Series Magritte, More from Series Magritte, & The Chorus of the Sphinxes — all also available as pdf downloads from Moria Books (http://www.moriapoetry.com/ebooks.html). Manzanita Leaves bursting like blossoms, Sprung from the first Good rain In seven years, Grace a thousand slender fingers. Those emerald wreathed fingers Weave morning light into life, And stretch toward a new moon Fleeing west - A crescent cup Holding its stolen treasure Of lucid sky. Robert Walton Robert Walton is an experienced writer with several dozen poems published. His novel Dawn Drums was awarded first place in the 2014 Arizona Authors Association’s literary contest and also won the 2014 Tony Hillerman Best Fiction Award. He is a retired teacher and a life-long rock climber. 1886 Smoking death through a cigarette, he passed the time- his eyes: glazed over with the look of the dead; his cheeks: the hollow worm meat long vanished from the sordid frame of his chiseled face. He was once so great, but I cannot remember what he did and now nobody would answer to his name, also forgotten, apart from existing, inked, on the slowly burning carcass in between his bony, blackened lips. He had written it there before, when capable, and now it burnt like his life before his glassy eyes, twisting and screeching, in agony at the horrors that were seen and the nothing he was to be. He was not yet put to rest, the dagger remained tattooed in his shrivelled veins; the day had not yet terminated but hung like loose threads before his head and fluttered in the wind, tormenting him in the everlasting light and the evanescence of before’s and again’s which now forgot to haunt him in his dazed state in which he remained, until the rain came down and covered his bones in mud and darkness, stamping out his smoky friend forever. He was left tearless in his grave of faeces and mud to spend eternity being the food for plants. Jasmin Deans Jasmin Deans has been writing for three years now. She is eighteen. She has recently moved to Dubai but will be attending university in the UK next year to complete an undergraduate degree in English Literature. She has previously been published in Rat's Ass Review. City Interior

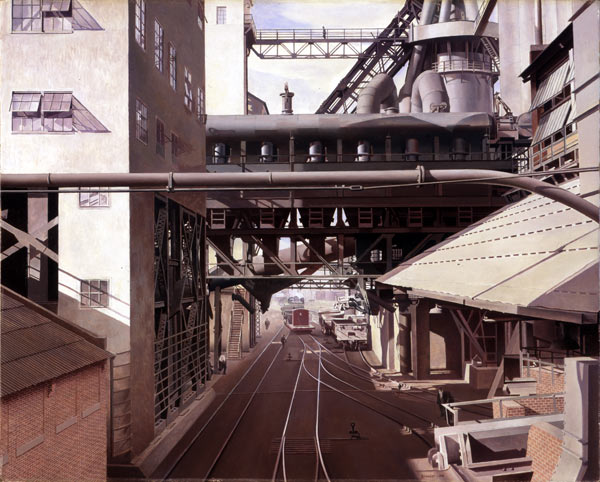

The painting is precise, photographic. It features industrial buildings with paned windows, a few propped open to release fetid air. It shows aluminium pipes and rivets, steel cables and junctions. The brickwork is meticulous. The perspective is definitive: five railroad tracks converge a third of the way up the picture - linking the world outside this painting to the dead centre of the canvas - and then they slip away into the bright indistinctness of the distance. This is a street in the heart of Detroit depicted in grey and sepia. The people in the painting are almost invisible by virtue of both size and colour. One by one they emerge, three men heading away along the front of the building on the left hand side, two men lower down to the right - a white man glancing back at an African American man. Starting a conversation? Ending one? Staring blankly through him? And then there’s the man anyone would miss, high overhead in the centre of the painting, walking across a gantry. The hatching on one of the steel cross members is detailed, the shadow of a window intricate, yet the people are indistinct pokes of a brush, almost incidental. This is the 1930s when Ford’s mechanisation of manufacture is king and men are ten a cent. While agricultural land decays into dust, this street in Detroit is pristine. Imagine a woman coming into the bottom right hand of this picture, an African American woman in a place where even the men barely belong. Perhaps she is heading towards the African American man - his wife or sister? But she ignores him, as though he is invisible, and steps over each of the tracks with a flick of her heel. And just as we think she is going to speak to the man in white shirt, we are startled to discover a seventh man, one with only one leg and one arm protruding from behind a vertical iron girder, his face barely visible under the peak of his cap. He is painted from the same blend of grey oils as the girder he is half-concealed by, and now we have seen him we wonder how we could ever have missed him, for it is this man that the woman is staring at as she purposefully crosses from right to left. “Frank.” The woman calls the name that she has used ever since the days when he delivered blocks of ice cut in winter from the great lakes and transported south by cart, by wagon, by train till they finally reached Plainfield. On the back stoop of Mrs Kennedy’s house she waited to watch as he took a saw to the dripping giant on the back of his truck, resting the off-cut on the wet piece of sackcloth slung over the shoulder of his leather vest. “Hoo-whee,” he said. “It’s a hot one.” And he raised a hand to his forehead, pretending to let the ice block slip, winking as she reached forward to prevent the contrived catastrophe. “Would you like me to set this in the ice box for you, Hattie?” In the painting the man doesn’t so much as smile, he glances around to see if any of the other men have noticed a woman in their midst, an African American woman at that, one who is now talking to him. He puffs out and then says, “Why you here?” “Sorry, Mister Finch.” She shouldn’t have called him Frank just now. She realises that in this formal city the codes that were bent on a back stoop are as absolute as the iron work surrounding them. She knows how the rules of this painting work. She adjusts her glove, hoping he won’t notice where the thumb and forefinger have worn through, and whispers, “It’s concerning your brother, Mister Finch.” And she searches the grey face shaded by the cap for a reaction, remembering when that face was sun-reddened, when the eyes reflected the blue sky and the cheek bones the white sun. She remembers the time before refrigerators reached Plainfield when ice came with a kiss and a tingle, when hands were held out of sight, the time when people had food in their ice boxes and stomachs. But the man won’t look at her. “Ain’t he dead?” he says. Hattie twitches her elbows to her sides, holding her purse firmly in her gloved hands, and notices the indent of a bristle across his forehead which speaks of guilt. He hasn’t written to his family back in Plainfield, not since who knows when. Now Hattie is here she partly understands why. Things are different here. There can’t be much to say about attaching fenders to automobiles, about precision. She’s got plenty she could tell this Mister Finch about Plainfield if he wanted to know, how the store’s closed down, how the cattle are all gone, how Mrs Kennedy moved to live with her sister somewhere in this city. “No, sir,” she tells him. “He ain’t dead.” The man straightens, but still remains in the shadow where he has been painted. His brother isn’t dead. All is well. No need to talk to her any more. He stares over her hat and Hattie is caught between one leg and the other, not comfortable on either. Not happy at being here in this painting at all. “He, Mister Finch, the other Mister Finch.” Hattie pauses. “It’s my sister Minny. You remember her, sir?” He nods. “Mister Finch, well he’s gone and, and now Mrs Gregory has let her go and she can’t feed herself let alone a baby. She gonna starve, Mister Finch, and he, the other Mister Finch, he don’t wanna know nothing at all. So I was wondering, whether you could see your way to giving her a dollar or two, just a bit, to keep her, for a little, till the baby comes.” The man pushes tightly to the girder. The man in the white shirt moves on obliviously, permanently in half-step, and the man on the gantry looks down on the scene, tapping the ash of a Marlboro. He doesn’t really have a role to play, just stuck up there by the painter to break the skyline. “I thought you might, you know, after, well,” she looks down. She wouldn’t be asking at all if it weren’t Minny, barely grown up enough to work let alone anything else, all skin and bones as it is. “Nooo,” he says slowly, shaking his head. Plainfield is as far away as the other side of the gallery. What happened back there, back then, means nothing, not here. “She’s carrying your blood,” Hattie says. He shifts, as though deciding on something. “I’ve got me a plan you see, Hattie,” he says. “Get me a tyre shop, make a little money. Need every cent I earn for my plan, I do. Can’t go sending none to Plainfield.” He settles back. He belongs here now, this is his world. “Could have been us,” she says, wishing she didn’t have to say it out loud, even if her voice is no more than a gallery whisper. “I could tell them that.” The man shakes his head. “Makes no odds to me,” he says. Hattie looks around at the scene depicted in this barely more than monochrome painting. The almost incidental people pictured are here for good, stuck together for ever, each alone. Who here cares about anything beyond the frame? And even though he is the man and she is the woman, he is white and she is African American, he has money and she has none, she feels sorry for the half-man the ice man has become. Ruth Brandt Ruth Brandt’s short stories have appeared in anthologies and magazines, including Aesthetica Creative Writing Annual 2017, Bristol Short Story Prize Vol 4, Litro, and Neon, nominated for prizes including the Pushcart Prize 2016, read at festivals and performed. She lives in Woking, England and has two delightful sons. www.RuthBrandt.co.uk |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|