|

Self-Portrait

Eighty you are, Alice, planted in a blue-striped chair, more naked than nude. In one hand you hold a brush like a baton, as if conducting your life, in the other, a rag for wiping out mistakes. Your breasts, like mine, droop over an abdomen poured like a land slump onto plump thighs. Pizza, pregnancies, peanut butter, whiskey, long sweet afternoons in the studio instead of in the gym. Turkey neck, jowls, marriage, divorce, paint under the fingernails. I see myself with the same down-turned mouth, the same skeptical stare and wonder how we got our bodies through it all. You used to say an empty chair by the window would be your only self portrait. Save that chair for me, Alice. I’m drawing close. Tell me how to come ashore. Ruth Bavetta This poem was first published in Ruth Bavetta's book, Fugitive Pigments (FutureCycle Press) and by Silver Birch Press. Ruth Bavetta’s poems have been published in Rattle, Nimrod, North American Review, Slant, Tar River Poetry, Spillway, Hanging Loose, Poetry East and many others. She has four books, Embers on the Stairs (Moon Tide Press,) Fugitive Pigments (FutureCycle Press,) Flour Water Salt (Futurecycle Press) and No Longer at This Address (Aldrich Press.) She writes at a messy desk overlooking the Pacific Ocean.

7 Comments

What Lies Beneath

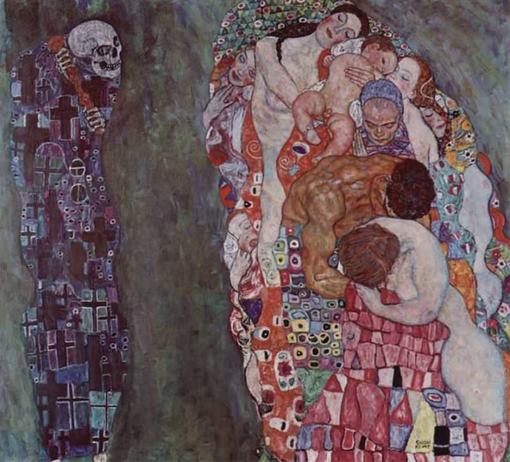

Entwined bodies wrapped in multi-coloured quilts of geometric shapes pieced together, bare limbs—hands & feet, legs & thighs, breasts & tiny penis, muscled shoulders & smooth flanks, young & old, calm smiles, some faces buried in their own arms, some nestle another’s shoulder or neck, skin alabaster & mahogany, all sleeping, except one woman—eyes wide open, staring from beneath the tangle. Quilts and bodies illuminate the darkness. Beyond the cast of light, a shade, wrapped in darker quilts of blue and purple, black crucifixes and circles, outlined in white, —a grim voyeur-- skull gazes from empty eye sockets, grin, more than skin deep, two skeletal hands grasp an object-- scepter for ruling the night? sword for battling the light? or a scythe for reaping? What lies beyond this waking dream of life & love age & youth wrapped in colour and diversity? What is the destination of this journey, this walk toward what we do not know-- this transformation this passage through the earth this rendering into most basic elements this crossing over? Reaper waits, sleepers dream. We all look the same when flesh is gone, when we open our eyes in that new darkness. Janet Ruth Janet Ruth is an emeritus research ornithologist living in New Mexico. Much of her writing focuses on connections to the natural world, but she is also an artist (pen-and-ink and watercolor), and so is inspired by the work of other artists to reflect on life. She has poems in Bird's Thumb, Santa Fe Literary Review, previously in The Ekphrastic Review, as well as in three volumes of Poets Speak Anthology - HERS, WATER, and WALLS, and Weaving the Terrain: 100-Word Southwestern Poems. She is finalizing the manuscript for her first book - Feathered Dreams: celebrating birds in poems, stories & images. https://redstartsandravens.com/janets-poetry/ Saddle Tramp

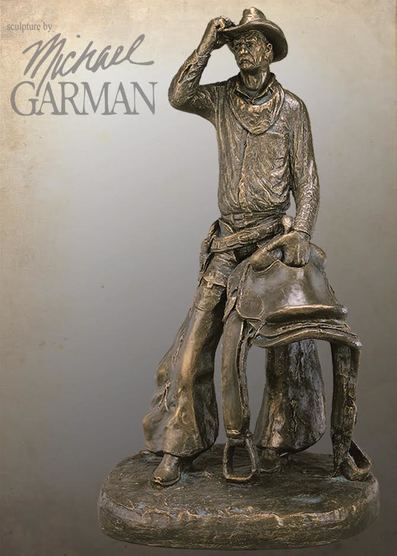

—like his saddle, spurs, and hat The horn, by years of lariat notched deep, holding a lassoed calf in summersault, the cantle low to speed the sideways leap, cinch wet with sweat, horse sliding to a halt —no conchos on this cowboy’s working saddle, host to stray calves, bedrolls, and dry canteens, borne aside lame mounts far from a stable, baptized in thunderstorms, immersed in streams; his hat a wrinkled map, sun, snow, and rain —Montana, Arizona, south to Mexico, mountains, great seas of grass, an open range— his hat a brand: the “saddle tramp,” “cowpoke”; spurs: to guide not goad, to say hello, —a pair of melancholy timbrels. Leland James Leland James is the author of seven books of poetry and a book on poetry craft. He has published over 200 poems worldwide, including The Lyric,Aesthetica, Rattle, The South Carolina Review, The Spoon River Poetry Review, New Millennium Writings, HQ The Haiku Quarterly, and London Magazine. He was the winner of an Atlanta Review International Publication Prize and the UK’s Aesthetica Creative Writing Award, and has won or received honors in many other competitions. in the USA, Canada, and Europe. Leland has been featured in Ted Koozer’s American Life in Poetry and was recently nominated for a Push Cart Prize. www.lelandjamespoet.com

Editor's note:

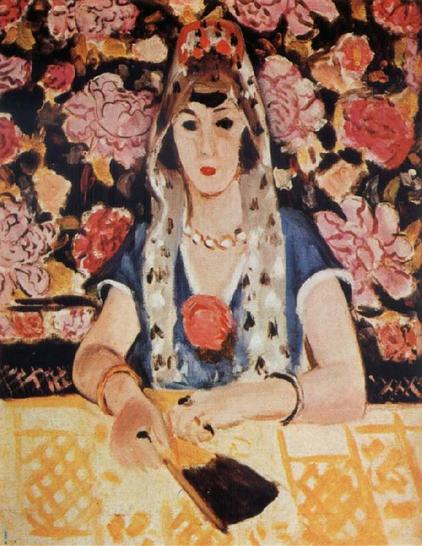

At long last, I'm finally starting my artist newsletter and mailing list. Those of you who enjoy following my visual art as well as reading The Ekphrastic Review are invited to subscribe. To be clear, this is Lorette's Art newsletter, not a Review update. (You can subscribe to the Review, too, top right of this page.) You will not be inundated with a thousand ad emails: I'm aiming for one to two mailouts per month updating you on my work and shows and special promotions. Thanks so much. Espagnole: Harmonie en Blue, 1923

Why shouldn’t the dead go on speaking? Here is a woman in a lace mantilla, black fan snapped shut, bangles on her wrists, arm resting on a table. Around her neck, a choker of pearls. She looks in my eyes straight as a shot of Cognac. Her mouth parts slightly. What is she trying to say? I have been listening, hoping to hear my own dead friends: Clare, Michèle, Adrianne. Snippets come to me in birdsong, in gesture, in the dark wing of a stranger’s hair. But it’s like deciphering code, or reading through water. The dead have their own language. Are they restless, do they long to come back, smell peonies in spring? Or is being dead enough, the end of the story, the book gently closing, and the conversation over? Barbara Crooker This poem was first published in Barbara Crooker's book, Les Fauves (C&R Press, 2017). Barbara Crooker is the author of eight books of poetry; Les Fauves (C&R Press, 2017) is the most recent. Her work has appeared in many anthologies, including The Poetry of Presence and Nasty Women: An Unapologetic Anthology of Subversive Verse, and she has received a number of awards, including the WB Yeats Society of New York Award, the Thomas Merton Poetry of the Sacred Award, and three Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Creative Writing Fellowships. Her website is www.barbaracrooker.com To Possess the Desert

The desert is an animal. It comes at you in layers. Just as you feel you have captured one element, it slips away and you are struggling to understand another. Soon enough it surrounds you, and your senses are immersed in the cicadas buzzing, the terracotta-colored soil, the potent chamisa and the dry, heavy air. Whatever you do will never be quite enough to fully contain the overwhelming emotion in the desert. You feel you want to possess it but you know you will never get there. The only way to capture it is to impose some sort of order. Agnes Martin’s works inspired by New Mexico make an attempt to organize the entropy of the desert. The pastel colored layers are as a close to an approximation of the entropy of the desert as I have ever seen. The washes blend into each other, as senses will fade, one into another, when you are amongst the cacti and soil. The layers are still there though, reflecting the endless noises, colors, scents and feelings of the dry land. I live away from the desert now , but I still want to dive into the noisiness, the smells, the heavy heat, the assault on my senses. When I want to go there, I look at Agnes Martin’s work, dive into it and let the desert wash over me. Molly Nelson Regan Molly Nelson Regan currently lives in New England and has worked at design, photography and writing roles and museums for the past several years. She uses her background in anthropology to write witty tweets about art. Outside of work, you will find her hanging out with dogs, skiing or doing anything ocean- or mountain-centric. With Pearls in My Hair One of the windows must be open; I feel a small breeze, almost a draft. It is practically impossible to get rid of the damp; the dark prints of mildew show everywhere. I find it is easier to remain motionless when I pay attention to the small things – trying to make sense of the faint household sounds from below, the indistinct voices, the, at times, hurried steps, and that final-sounding thud of the front door. At other times, I try to distinguish between the different kinds of bells tolling from the many church towers surrounding us. Right now, there is the unmistakable sound of water being sloshed on the cobblestones below; I keep listening, even while I watch the shimmering rectangle of light gaining purchase on the room. Sitting still like this for any length of time, while Rembrandt works in virtual silence, felt strange at first. I remember how uncomfortable I used to be under his gaze. I know his work, and know how it speaks of an eye that sees more than most. Just take his latest portraits, or his many self-portraits! Fine details are what he loves, small values in lines, the offset of shadow and light, and their dissolving into half tones... while I do not understand most of what he explains to me, I do know that he catches the essence of a person better than most, and often, better than one would like. The very first time he drew me could hardly have been called a sitting. It was on the third day after our betrothal, we were out in the country visiting my sister, when he called out to me, “Just stay like that, Saskia!” while he opened his sketchbook and started drawing. Watching him draw I was amused, and later on when he gave me the finished drawing, enchanted. This incident has remained one of my favourite memories of that outing. In the finished sketch I am wearing my much-loved, generously brimmed straw hat and I am holding an already wilting flower that I could not help picking while we ambled in the garden. Looking at the drawing now, I am amazed at the innocence and vulnerability of my expression. Today, Rembrandt asked me to arrange my hair using my long string of pearls; he suggested I wind it through my swept up hair. I had to rearrange my hair several times before he was satisfied and just the right number of stray curls framed my face. I’m also wearing my double strand of pearls and the pearl earrings that go with it. The dress he chose for me is the festive brown one with the ruched and bound sleeves. No, I find I do not mind sitting still like this – it frees my mind to keep my gaze locked on a certain point, and it allows me to drift to a place of listening and sensing, rather than acting. It feels peaceful and timeless and my mind drifts to thoughts I hold dear. Lately, I have wondered whether I might not be with child. Then I ask myself, would I know it if I were? The deep contentment that I feel, this sense of inner calm, this feeling of waiting for something as yet unknown, could that be part of it? We have not been married for very long. Being the wife half of “husband and wife” still feels strange to me. I have come to realize that in many ways my life so far has left me woefully unprepared for my role as a wife. I was only seven when my mother died and twelve when my father died. Perhaps I will not know how to make a good life for us, or how to be a good mother. I know my friends would think it tiresome to sit like that, and it is hard not to drift off to somewhere else, but I know Rembrandt does not mind where my mind goes as long as I do not move a muscle. The air coming in through the open window smells more and more like rotting fish and given the brackish water in the gracht down below this is hardly surprising. The odour sparks memories of Friesland where I grew up. How much cleaner the air had seemed to me at the North Sea and how much more powerful the force of the wind. I have a vivid picture of myself running along the damp beach at low tide daring the waves to touch me; and I remember coming home with the damp hem of my skirts clinging to my bare legs, leaving anklets of salt on my calves. Over there, at the other end of the room, at the very edge of my focus, I can barely make out Rembrandt’s latest self-portrait. It’s the one with the soft cap which, by the way, I can see he has dropped carelessly on the chair in the corner just below my red velvet hat hanging on the wall. That portrait shows a more private side of Rembrandt, the softness and ardour that are his as well, but that are often missing from his other self portraits. Perhaps I’m being fanciful, but I think that in some small way I have contributed to that expression, that new openness. I will suggest to him that we keep that portrait solely for ourselves, and for our children, who will, God willing, one day fill our lives. It is a fulsome quiet that fills the room, the only sound comes from the movement of the burin scraping the copper plate. Rembrandt explained to me once that the small curls of copper that are thrown up by the tool grooving the plate, will, once inked, give the image its soft lines and suggest shadows and fluidity. It seems to me an inexact way of working, as if part of the effect was left to chance, was unpredictable and unstable. The bells have started ringing again. I fancy I can make out the massive bell of the Westerkerk. There are so many churches and carillons all over Amsterdam, especially in this part of town, and so many of them start and finish just slightly out of step with one another. Yet each has its own distinctive tone, its own melodic voice of hymn and psalm that strive and merge only to be eventually drowned out by the general discord of everyday sounds, by the very life teeming around it. Here in the studio, time in its very timelessness is passing as well. Postscriptum: The next year, 1635, was going to be one of the worst plague years in living memory. One in five people in Amsterdam was about to die. Saskia was to bear Rembrandt four children, three of whom would die in infancy, one at the age of twenty-six. Saskia herself died at age thirty from tuberculosis. Rembrandt would live on until 1669. Barbara Ponomareff Barbara Ponomareff has been a child psychotherapist by profession. Since her retirement she has been able to pursue her life-long interest in literature, psychology and art. She has published a novella on the painter J.S. Chardin, and her short stories and poems have appeared in various literary magazines and anthologies. The Monographer With apparent forethought and generous attention to margins and spines, some resourceful bookbinder has pasted The Night Watch into place. But it’s hard to say pasted without underestimating a toothpick’s precise caulking, or tailors who stitch invisible hems or bricklayers who forgive the bricks for their lazy adhesion and easy stacking. Whatever mistake the printer admits to, the cover-up is as flawless as the captain’s fingernails blended into the lattice of his outstretched hand. Silent, satin glue holds the replica as honestly as the watchman holds his lance, as secretly as the golden girl hangs her chicken by its claws. Amy Nawrocki Amy Nawrocki is the author of five collections of poetry, including Four Blue Eggs and Reconnaissance. Her most recent work is The Comet's Tail: A Memoir of No Memory published by Little Bound Books. She teaches English at the University of Bridgeport and lives in Hamden, Connecticut. Visit her at http://amynawrocki.org. Enter

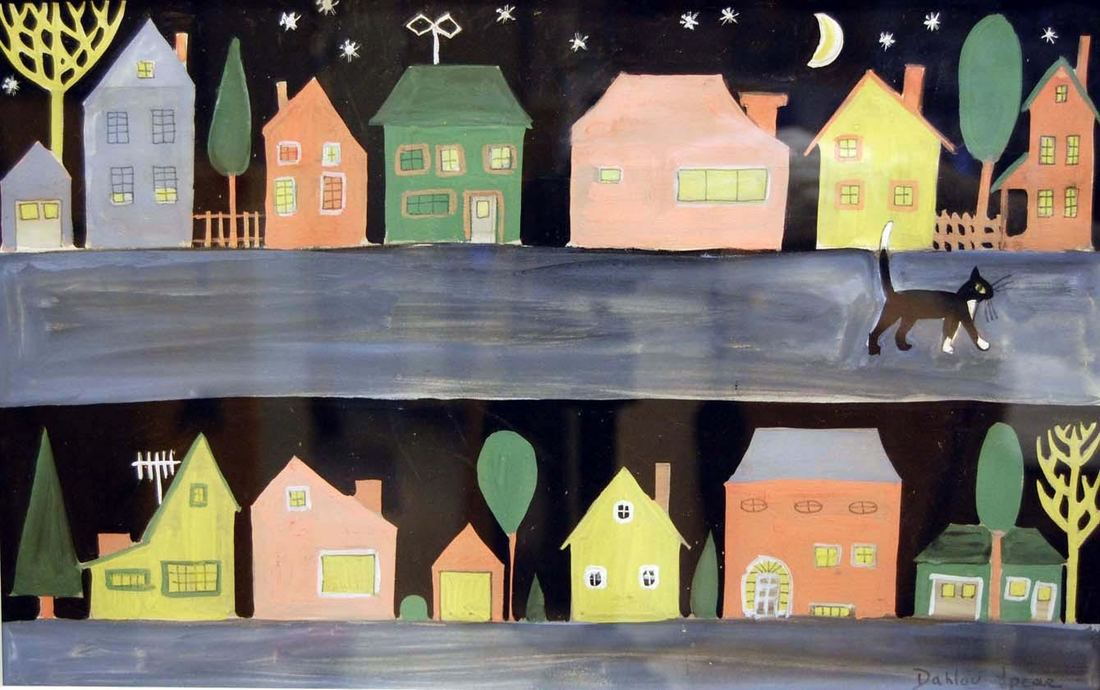

And there is no object so soft but it makes a hub for the wheel'd universe —Walt Whitman Let us stand side by side in our nighttime simplicities, in our humble shapes, our several soft colours. Let the trees reach and the stars be clear and the moon bend gently above us. Let even our irritable antennae be for once lit and innocent, as if made by a young child with large eyes and wide mind, while a confident cat walks the gray and subtle surface of things, unshadowed, liquid. Shirley Glubka Shirley Glubka is a retired psychotherapist, the author of three poetry collections, a mixed genre collection, and two novels. The Bright Logic of Wilma Schuh (novel, Blade of Grass Press, 2017) is her latest. Shirley lives in Prospect, Maine with her spouse, Virginia Holmes. Website: http://shirleyglubka.weebly.com/ Online poetry at The Ekphrastic Review here; at 2River View here; at The Ghazal Page here; and at Unlost Journal here.

MoMA’s Pond Wandering galleries filled with Van Gogh, Picasso, Matisse, I find a dim room, its curved wall lit with a stretch of saturated blue, water lilies, reflection of sky and pink-tinged clouds. A golden-haired woman, face soft with wonder, studies curator’s notes, turns toward the artist’s pond. Drawn by certain joy, I approach-- Have you been to Paris, Musée de l’Orangerie? It has canvases like this one, I say, Monet’s gift to the country he loved. With a shake of her head, she speaks, reveals distance traveled to walk along this shore. She smiles, enters Giverny, gifts this silhouette of a sonnet to me. Diana Dinverno Diana Dinverno was a finalist for the New Rivers Press 2015 Short Story Prize. Her work appears in The MacGuffin, Peacock Journal, Peninsula Poets, and American Fiction, Volume 15: The Best Unpublished Stories by New and Emerging Writers. More at: dianadinverno.com. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|