|

Library Discard: A Collection of Senryu

SALE TODAY! greeted by the smell of old books memories of childhood . . . lightly my fingers on the book spines guilty pleasures and beach-reads: these paperbacks my personal space and that one pushy person shadowing me stuck between pages: pressed pansies heavier than the entire internet this unabridged dictionary cat book -- one page dog-eared outdated encyclopedias: she buys a complete set for collaging Bill Waters Bill Waters is a well-published writer of short poetry and compressed prose. He also runs the Poetry in Public Places Project, a Facebook / real-world group interested in creating and promoting poetry in public spaces to increase the richness of everyday living. Bill lives in Pennington, New Jersey, U.S.A., with his wonderful wife and their two amazing cats. See 150 square foot works by Lorette C. Luzajic at www.squarefootartbylorette.ca. Use the coupon code EKPHRASTIC50 to receive $50 off. Shipping is always free. Your purchase directly supports the development and maintenance of The Ekphrastic Review.

0 Comments

The Movie

“It is the blight man was born for, It is Margaret you mourn for.” -“Spring and Fall: To a Young Child,” Gerard Manley Hopkins In the dark, we watch a wall that shimmers light from a cubicle outside the almost-empty room. Somewhere not here, a bird sings, then plummets toward Goldengrove’s dying. We hear the sad trill in the score, recognize its ghost of an image on the decades-old screen, in its stabbed-in-the-heart theme cocky enough to stalk the poem and take its lines hostage. Even so, the camera has panned our sorrow perfectly: all the world’s turmoil in that first burst of leaves dropping their gold as when Lonergan directs his carefully orchestrated bus to screech into distraction, into death, into all the cinematic close-ups of blame as weak as Adam’s first disclaimer, as pale as the guilt-stained cheeks of Paquin, who won’t stop screaming incriminations she can’t fix, immortality thrown under City Transit thanks to Special Effects expertly bleeding grief that even now wells up in each character and, yes, in us, Hopkins’ autumn as fresh as the credits flashing their momentary light as we linger too long in the familiar local theatre strewn once again with popcorn and empty, crushed boxes of Dots. Marjorie Maddox This poem was originally published in Marjorie Haddox's book, True, False, None of the Above (Poiema Poetry Series, Illumination Book Award medalist). Click here to read "Spring and Fall" by Gerard Manley Hopkins. Sage Graduate Fellow of Cornell University (MFA) and Professor of English and Creative Writing at Lock Haven University, Marjorie Maddox has published eleven collections of poetry-including True, False, None of the Above; Wives' Tales; Local News from Someplace Else; Perpendicular As I; Weeknights at the Cathedral; and Transplant, Transport, Transubstantiation; the short story collection What She Was Saying; the anthology (co-editor) Common Wealth: Contemporary Poets on Pennsylvania and four children's books. For more information, please see www.marjoriemaddox.com Piero di Cosimo’s Saint John

This Evangelist is a paradox. His face so gentle, so benign, transcendent with love of God and mankind, too-- belies his powerful hands, muscular of palm, thick of wrist. These are the hands of a man you would not want to wrestle with, but, strangely, they are also the hands of a saint so pure he persuades poison to depart as snake. They are, we also know, the hands of Christ’s best friend who sticks with his Jesus to the bitterest of ends. And these are the hands, that will, at the last, craft the fiercely lovely poetry, the words that will be revelations. Joseph Stanton Joseph Stanton has published five books of poems. His most recent, Things Seen, is an ekphrastic collection. His poems have appeared inPoetry, New Letters, Antioch Review, Harvard Review, Ekphrasis, and many other journals and anthologies. He is a Professor of Art History and American Studies at the University of Hawaii at Manoa. He occasionally teaches poetry workshops, such as the “Starting with Art” workshops he has taught recently at Poets House (in New York City) and the Honolulu Museum of Art. For more information on Stanton's latest ekphrastic collection see:http://brickroadpoetrypress.com/order-books/things-seen-by-joseph-stanton Metal Man

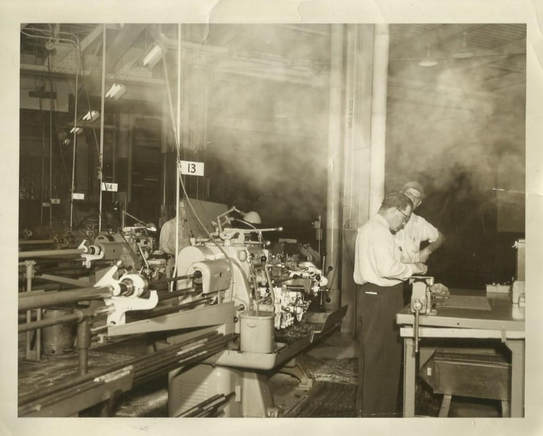

More Hephaestus than Daedalus, my grandfather calibrates some small piece of history into a dream machine that flies me back to this time and place where men are men and progress is forged by the pull of a rubber-balled steel lever, where pistons throb in and out of metal wombs and what is birthed is one feather of one wing of Hermes’ left sandal, but line up enough of these copulation engines, seventeen, say, as the pennants unfurled in the metallic wind at my grandfather’s back suggest, and you assemble the whole monster, just slap a TWA or a United on it and point it in the direction of Olympus. And that cloud there, emanating from the nape of my grandfather’s neck, that’s his fifth grandchild, my brother, entering the world with no mechanical assistance, my grandmother bleeding her cancer into the cup of her bra, my dad taking the civil service exam that will lead to his heart attack five years later, me typing this whole fugue out in the rarified air of Cyberspace where the womb of industry can fit on the head of a virtual pin and gods come and go via Snapchat and Instagram. Should I tap my grandfather’s Stoic shoulder, warn him of the extinction of his species, the scrap pile his world will become? Better, perhaps, to let the goggle-eyed, cocked-arm assistant who is peering over Hephaestus’s crew cut and out of his time into mine regale the god with tales of awe and wonder over a baloney sandwich and a cup of joe when the lunch whistle blows. Robert L. Dean, Jr. Robert L. Dean, Jr.'s work has appeared in Flint Hills Review, I-70 Review, The Ekphrastic Review, Illya’s Honey, Red River Review, River City Poetry, Heartland!, and the Wichita Broadsides Project. He read at the 13th Annual Scissortail Creative Writing Festival in April 2018 at East Central University in Ada, Oklahoma. His haibun placed first at Poetry Rendezvous 2017. He was a quarter-finalist in the 2018 Nimrod Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry contest. He has been a professional musician and worked at The Dallas Morning News. He lives in Augusta, Kansas. But You Could Laugh at Our Hopelessness

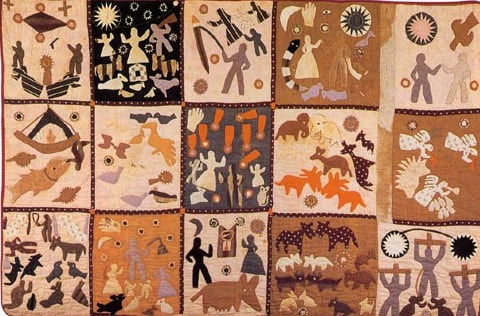

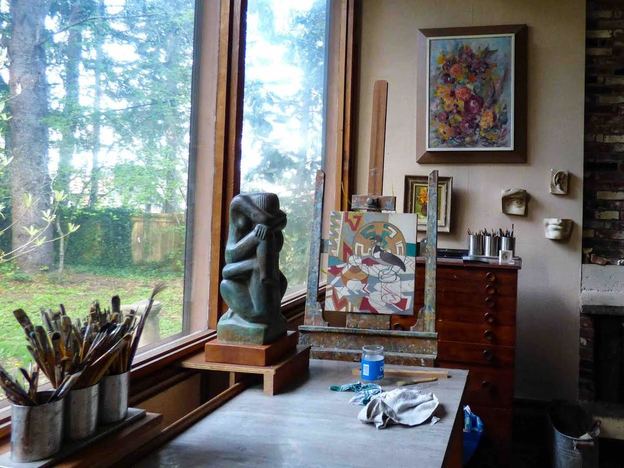

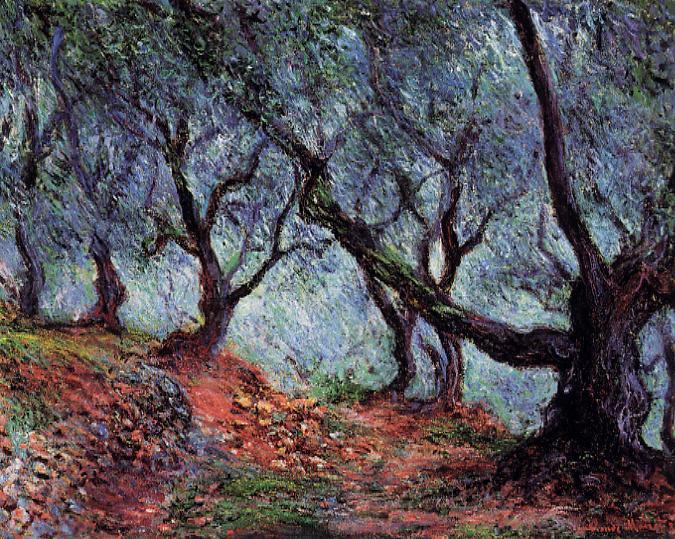

A hard division splits two panes to the right of centre. Graffiti climbs from its concrete and inhabits us at the underpass. Clouds consume our excesses, bear the grease of machines long-since retired. We are cloistered in the perfect place to make things that matter to almost no one. Taught to crouch under our desks when the sirens sounded and not much else, the open spaces slow us down, interrupt our languages with wind and dust. We court fear like a darker world might bolster this by comparison. The gold-trimmed failure is a crown and those around us care too much to even let us down easy—it’s not a metaphor that Cato’s daughter swallowed fire.(1) Brows furrow at the edge of questions and daylight’s running down. A lone fox- glove spills pink against the backdrop of a tincture-blue sky dulled by the threat of storm. More and more we veer toward silence in the hours that are actually ours. 1) Words borrowed from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, Act 2, Scene 1/Act 3, Scene 3 Nano Taggart This poem was previously published in Terrain. Nano Taggart probably likes your dogs better than his neighbours, and is a founding editor of Sugar House Review. By day, he works as a fundraiser for the Utah Shakespeare Festival. By night, he researches new hot sauces for his collection. He's a co-recipient from a grant from the Utah Division of Arts and Museums, and you can see some of his stuff in Terrain.org, Verse Daily, The American Journal of Poetry, and on some beautiful broadsides for sale at Art Works Gallery in Cedar City, Utah. After The Revolution, Mine Eyes See Inferno i. Araminta’s temple spews fury mixed with a ghost-whisperer’s song that leads them to the promised land ii. moths to the flame of new land donkey-eagled men trampling on blood- stained soil, hell fire below, fly away iii. fly, fly, fly - Lincoln is spread eagle cowering behind the black bone of slavery bear a mother’s cross for Christ’s sake, amen iv. a man sees her face downcast, then sees her face again, differently / her headless bonnet a mile post along Jubilee Street v. embers burn upon her chest nipple-feeding armies sag under the press of deadwood colonies vi. scratch the amen corner in blue & orange voices are fire & vapor / traveling oceans to find the cut throat where the deceased's cries lie vii. the ancestors’ handprints fist children into recovery / reparation is to see the slave man whose bottom half viii. is blood / your rage is protesting the time it takes to make blood boil / what is a lifetime? ix. New York is under siege / the Plains are on fire the Mississippi’s overrun with kink & tears / scratch tragedy into a map, then look again: divine comedy. .chisaraokwu. Editor's note: The quilt shown above is a remarkable artwork from the late 19th century, by African-American artist Harriet Powers. As beautiful as it is, this is not the image that inspired .chisaraokwu. to write: rather, it is a placeholder as we were unable to contact the artist whose work inspired the poem. Please click here and scroll down to see this amazing piece, Looking At Me Funny, by Mark Bradford (USA). .chisaraokwu. is a poet, actor & healthcare futurist. She is grateful to have had her works published in many literary and academic journals. She is passionate about addressing trauma through the arts, is semi-obsessed with the indigenous religious traditions of the Igbo of eastern Nigeria and completely obsessed with the Italian language. Find her on IG: @naijabella. Fang Mask Elongated wooden face whitened with kaolin. Features tinted brown topknot, too. No words from lips no blinks in the gaze from my wall. Yet evil spirits flee thieves kneel. Handsome art or talismanic charm? I pat his narrow nose each evening not knowing what he knows. Janice Ericson Janice Ericson is a poet living in Jamaica Plain, Massachusetts with her wife of 27 years. She has been a member of a poetry workshop for almost ten years led by Tom Daley in Boston. She has not submitted many poems for publication but hopes to change that now that she is retired and can devote more time to writing poems and finding homes for them. Two Studios Creators need space. —Priscilla Long I was homesick in New Orleans when I stepped into your studio. It was 1983. A job for my husband, David, had brought us to the city. As I struggled to find a remedy, to find something familiar in a place that felt foreign to me, you opened that blue-green door just off Pine Street and I found home. Not that your studio had the smell of Western red cedars nor vistas of Cascade volcanoes nor crash of Pacific Ocean breakers, all gems in the crown of my home ground in the Pacific Northwest of North America. No, your studio, the one you built with your father in 1928 so you could launch your work as a sculptor when you returned home from Paris, was set less than a half mile from levees along the Mississippi River. Sweet Olive trees perfumed your brick patio and the walls of your studio were lined with barge board salvaged from flat bottom boats that once floated down the River. There were certainly no mountains in view in New Orleans. Anywhere. For miles and miles. For forever it seemed to my Northwest eyes. The landscape was as flat as the bottom of those old boats. But I found home in your artist’s habitat, within your welcome and warmth and laughter and stories. Like a loose blob of clay I happily stuck myself onto the armature of your long history of life as an artist in Louisiana. I listened to your memories of sculpting monuments cast in bronze for plazas in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, your work on bas reliefs for the state capitol built in 1932, on architectural sculpture for the Tulane University buildings where I worked as a writer. In your studio—below the high windows that allowed the light to pour in, within the presence of your sculptures of stone, bronze, plaster, of paintings on easels, paintings stacked on the balcony, for you were also a very good painter—I settled in. Together we took up the long work of writing the story of your years as a young artist in Paris, years that set you, Angela Gregory, on your track to a six-decade career as a sculptor in your home territory of Louisiana. Lately I have queried the remedy for homesickness I found in your studio. It was you, of course, and the deep friendship we built as we worked together. But there was something else and now, looking back, I see that the familiarity I found within the foreignness of New Orleans was seeded in my adolescence when I spent time in another studio near Portland, Oregon in my hometown of Tigard. That Tigard studio belonged to Blanche and Albert Patecky, painters both, and their sculptor son, Kenneth. They had built it themselves in 1960. When I was a teenager I went there once a week for piano lessons from Blanche, who was also a composer and musician. She and Albert were about the same age as you, Angela, born in the early 1900s. “Mrs. Patecky,” as I always called her, was warm and kind and had agreed to the bargain I had made with my mother: I would keep going with piano lessons only if I did not have to play in recitals for I hated the tension, the nervousness, the preparation and practice required. That studio in Tigard was similar to yours: a wall of windows that let in lots of light, paintings on easels, brushes, palettes smeared with paint. And sculptures, too, by Kenneth. Blanche often painted bouquets of flowers: pink peonies, yellow daffodils with orange centres, the blues and purples of hydrangeas. Albert worked in non-objective, sometimes abstract, art. Now I know he is considered a pioneer of nonrepresentational art in Oregon. Often, while Blanche and I sat at the piano during my lessons, Albert stood at an easel working on a painting. Through the windows Kenneth’s works of human figures in cast concrete anchored the lawn that stretched long and green in the Oregon rain. I have been in touch with Kenneth recently. He is now in his 80s and is lovingly curating, preserving the artistic legacies of his parents. From him I have learned more about Blanche: as a young woman of 19 she performed in Portland as a professional pianist and pipe-organist; she toured ten Western states as part of an Ellison-White Lyceum traveling stage performance; she was not only a talented painter but also a gifted composer of piano music. Albert and Blanche married when she was 25 in 1930. Kenneth is their only child. Blanche was not like you, Angela: you had made the difficult decision to never marry or have children. Determined to be a sculptor, you knew that marriage and family would destroy your dream. You grew up understanding that your own mother had given up life as a serious artist when she married your father, birthed and raised your brother and sister and you. Blanche’s chosen path as practicing artist, wife, and mother meant sacrifices, too. According to Kenneth, she was “steadfastly dedicated” to helping Albert “succeed as an artist often at the expense of her own potential.” She was the one who stayed behind in Portland with young Kenny while Albert spent three months in New York in 1945 at the Art Students League. After his return, the income from sales of his paintings was not enough to support the family so Blanche began giving private piano lessons to sustain finances. The Pateckys lived in an apartment behind their Tigard studio. Not dissimilar to you, Angela, for in those years I knew you toward the end of your life, your Pine Street studio, with attached bedroom, bathroom, and kitchen, was also your home. Certainly the Pateckys were anomalies within my home landscape of Tigard. My family knew no other practicing artists; their unfamiliar profession felt foreign. They had made art their life, made financial sacrifices, angered parents by their choices. Unlike you, Angela, who had the good fortune of supportive parents. You had known early on in your life what you wanted, and at fourteen you completed your first-ever sculpture. In a September 1918 letter to your father, serving in France during World War One, you wrote “I have decided to be a sculptor—how do you like that? I made up my mind long ago to be an artist & I think I will like that best of all.” Sculpting was an unconventional path for a woman born in 1903, an era when few women had careers, but you were determined. I recently read a book of letters that Blanche and Albert wrote to each other while he was away in New York, learned about their struggles, their commitment to a life of art. Blanche to Albert, March 1945: “My dad thinks we will never make a living with art in Portland. I told him if we can’t we will have to go where we can, that’s all.” Albert to Blanche, February 1945: “So Blanche, you must look ahead and enjoy nature and we will get along in life. What we need is wholesome, good, clean mental stimulation, sunshine and rest. Let us acquire those things first. Then we will build our bodies and fertilize our minds with stimulating thought and constructive enterprise. The money will come its own way as a reward for our efforts.” My Tigard friend Joyce, who also took piano from Blanche, recalls arriving for a lesson and seeing on an easel a painting of a bouquet of flowers. Behind the easel sat the real bouquet of fresh blooms, the ones just painted. This is not my memory, of course, but I am intrigued by the alchemy of artistic transformation, that move from vision to execution. Joyce’s recollection has spawned my curiosity: Was Blanche satisfied with her painting? Did she feel she had achieved her vision, that the painting had survived the transformation? In Art and Fear David Bayles and Ted Orland write that “a finished piece is, in effect, a test of correspondence between imagination and execution.” Did the painting pass that test for Blanche? What were the differences between the real bouquet and her painted image? Were the flowers from her own Tigard garden? I imagine her carefully picking each bloom for color and freshness, then arranging them artfully. Did she use oil or watercolor paints? If watercolor, there would be little opportunity for changes; the painting that Joyce saw would probably have been finished, the transformation complete. If oil, she could have much more easily returned to work on it again; even after the flowers had faded, the possibilities would still be open. You, Angela, as a young artist in Paris studying with French sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, witnessed this kind of transformation from reality into art when you watched him work on a clay model of a woman posing. Within that fertile and creative atmosphere of his Montparnasse studio, he narrated his motions, his artistic decisions as a lesson for you. Normally his wife, Cléopâtre, “was the only one allowed to stay in the room while he modeled because of the intense concentration required,” you told me. Watching Bourdelle work was a great privilege, the most exciting and educational experience of your three years in Paris. As a teenager in Tigard, I had soaked in the atmosphere of the Patecky studio. Under the gentle duress of my mother, I sat at the piano keys as an object of discipline and practice. But is that not the artist’s way? That combination of creativity and hard work? I began to absorb the creative worker’s way of life expressed in that studio, the examples of Blanche and Albert and Kenneth’s lives. This is the phenomenon of influence on a young person by adults, even if the young one is unaware of it, as certainly I was at the time, blurred by the hormones of adolescence. Only now, looking back, do I see what I learned, how I was changed. What is it about these artist studios? Do they speak to my own evolution as a human with long-ago ancestors who used red ochre paint to create images of hands pressed against the walls of caves? Reza Aslan writes in God: A Human History that “the oldest handprints go back some 39,000 years and can be found not only in Europe and Asia, but also in Australia, Borneo, Mexico, Peru, Argentina, the Saharan desert, and even the United States.” Ubiquitous. My human ancestors creating art. Even earlier than the oldest handprints, 100,000 years ago in Blombos Cave in southern Africa, humans “created an artist’s studio where they ground red ochre and stored it in the earliest known containers, made from abalone shells,” writes Heather Pringle in Scientific American. The purpose is unknown; perhaps to adorn bodies or clothing. A type of studio nonetheless. I can believe this inherently human impulse to create art in a protected space is what resonated with me in that Tigard studio, seeped into me and stayed. So that all those years later, when I was an adult and stepped into your studio off Pine Street, Angela, I was home. The Patecky studio in Tigard had once been foreign within the familiarity of my home landscape, yet that atmosphere of creativity became woven into the fibers of my memory. What had once been foreign to me in Oregon made your studio in Louisiana seem familiar, feel like home. And is this not what has happened to me over and over in my life as I have lived and traveled many places? The foreign becomes familiar until it feels like home. These two studios—both sheltered spaces for creating art—shaped my vision of self as creator, writer. Certainly part of my good fortune is to have a room in my Seattle home for writing, a protected space for my creativity. As Gaston Bachelard in Poetics of Space explains, “The house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” In reconsidering these studios in Tigard and New Orleans I have excavated an unrecognized dream: I crave a space full of windows and light; easels with paintings in progress; brushes corralled upside down, their bristles and tufts poking out of old porcelain vases; palettes smeared with colours like citrine, carmine, cerulean, fuchsia, celadon, imperial purple. I want, like Blanche, to make beautiful paintings of bouquets of flowers. I want, like you, Angela, to live surrounded by my art. Perhaps I will search for a light-filled space and take up brushes loaded with colour. Perhaps I will become a painter. Nancy Penrose ar labhair tú, a mhaoin leis na crainn ológa nach casta iad a gcuid scéalta is nach ársa beir ar lámh orm have you spoken, beloved to the olive trees how convoluted their stories and how ancient take my hand cuir lasair faoi m’aisling cuir fíor na spéire trí thine dóigh m’inchinn déan íobairt díom, a thaisce más toil leat é burn my vision – set fire to the horizon to my brain make a sacrifice of me beloved, if you will ar éist tú leis an nuacht

nó, mo dhála féin, ar thugais cluas do na géanna an leigheas is fearr, a stór ar bharraíocht eolais sweetheart, heard the news? or, like me, do you hearken to the prattling of geese perfect antidote to information overload Gabriel Rosenstock Gabriel Rosenstock was born in postcolonial Ireland. He is a poet, translator, haikuist, tankaist, playwright, essayist and novelist. Falling

When you’re lost under the milky streetlights of Jan Pieter Heijestraat & all you can feel is a stranger’s gaze lingering one second too long, Amerikaans, it feels like falling into the varicose veins of Van Gogh’s blue-tinged body, succumbing to The Harvest’s molten fields, Starry Night’s angry skies. There’s something about the movement of his brushes that is like the movement of the city – something unforgiving, deafening. But even Van Gogh couldn’t paint the ever-present ringing of bells, clinging to canal boats & their windows like a stranger’s golden eyes, more awake than alive. Nooshin Ghanbari Nooshin Ghanbari is a recent graduate of the University of Texas at Austin with degrees in English and Plan II Honors. While at university, Nooshin was awarded the Board of Regents’ Outstanding Student Award in Arts and Humanities for excellence in poetry, the Ellen Engler Burks Memorial Scholarship for Creative Writing, and the James F. Parker Prize in Poetry. Her work can be found in WILDNESS, Apricity Magazine, Vagabond City Literary Journal, Skylark Review, and elsewhere both nationally and internationally. Nooshin currently lives in Austin, Texas, where she works as an AmeriCorps literacy tutor in low-income elementary schools. Website: https://nooshinghanbari.wordpress.com |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|