|

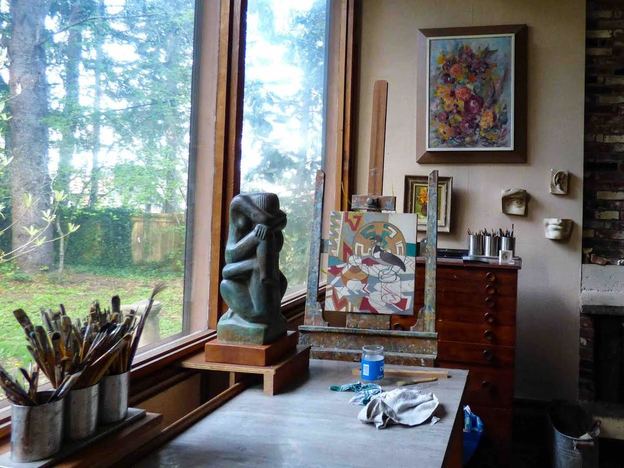

Two Studios Creators need space. —Priscilla Long I was homesick in New Orleans when I stepped into your studio. It was 1983. A job for my husband, David, had brought us to the city. As I struggled to find a remedy, to find something familiar in a place that felt foreign to me, you opened that blue-green door just off Pine Street and I found home. Not that your studio had the smell of Western red cedars nor vistas of Cascade volcanoes nor crash of Pacific Ocean breakers, all gems in the crown of my home ground in the Pacific Northwest of North America. No, your studio, the one you built with your father in 1928 so you could launch your work as a sculptor when you returned home from Paris, was set less than a half mile from levees along the Mississippi River. Sweet Olive trees perfumed your brick patio and the walls of your studio were lined with barge board salvaged from flat bottom boats that once floated down the River. There were certainly no mountains in view in New Orleans. Anywhere. For miles and miles. For forever it seemed to my Northwest eyes. The landscape was as flat as the bottom of those old boats. But I found home in your artist’s habitat, within your welcome and warmth and laughter and stories. Like a loose blob of clay I happily stuck myself onto the armature of your long history of life as an artist in Louisiana. I listened to your memories of sculpting monuments cast in bronze for plazas in New Orleans and Baton Rouge, your work on bas reliefs for the state capitol built in 1932, on architectural sculpture for the Tulane University buildings where I worked as a writer. In your studio—below the high windows that allowed the light to pour in, within the presence of your sculptures of stone, bronze, plaster, of paintings on easels, paintings stacked on the balcony, for you were also a very good painter—I settled in. Together we took up the long work of writing the story of your years as a young artist in Paris, years that set you, Angela Gregory, on your track to a six-decade career as a sculptor in your home territory of Louisiana. Lately I have queried the remedy for homesickness I found in your studio. It was you, of course, and the deep friendship we built as we worked together. But there was something else and now, looking back, I see that the familiarity I found within the foreignness of New Orleans was seeded in my adolescence when I spent time in another studio near Portland, Oregon in my hometown of Tigard. That Tigard studio belonged to Blanche and Albert Patecky, painters both, and their sculptor son, Kenneth. They had built it themselves in 1960. When I was a teenager I went there once a week for piano lessons from Blanche, who was also a composer and musician. She and Albert were about the same age as you, Angela, born in the early 1900s. “Mrs. Patecky,” as I always called her, was warm and kind and had agreed to the bargain I had made with my mother: I would keep going with piano lessons only if I did not have to play in recitals for I hated the tension, the nervousness, the preparation and practice required. That studio in Tigard was similar to yours: a wall of windows that let in lots of light, paintings on easels, brushes, palettes smeared with paint. And sculptures, too, by Kenneth. Blanche often painted bouquets of flowers: pink peonies, yellow daffodils with orange centres, the blues and purples of hydrangeas. Albert worked in non-objective, sometimes abstract, art. Now I know he is considered a pioneer of nonrepresentational art in Oregon. Often, while Blanche and I sat at the piano during my lessons, Albert stood at an easel working on a painting. Through the windows Kenneth’s works of human figures in cast concrete anchored the lawn that stretched long and green in the Oregon rain. I have been in touch with Kenneth recently. He is now in his 80s and is lovingly curating, preserving the artistic legacies of his parents. From him I have learned more about Blanche: as a young woman of 19 she performed in Portland as a professional pianist and pipe-organist; she toured ten Western states as part of an Ellison-White Lyceum traveling stage performance; she was not only a talented painter but also a gifted composer of piano music. Albert and Blanche married when she was 25 in 1930. Kenneth is their only child. Blanche was not like you, Angela: you had made the difficult decision to never marry or have children. Determined to be a sculptor, you knew that marriage and family would destroy your dream. You grew up understanding that your own mother had given up life as a serious artist when she married your father, birthed and raised your brother and sister and you. Blanche’s chosen path as practicing artist, wife, and mother meant sacrifices, too. According to Kenneth, she was “steadfastly dedicated” to helping Albert “succeed as an artist often at the expense of her own potential.” She was the one who stayed behind in Portland with young Kenny while Albert spent three months in New York in 1945 at the Art Students League. After his return, the income from sales of his paintings was not enough to support the family so Blanche began giving private piano lessons to sustain finances. The Pateckys lived in an apartment behind their Tigard studio. Not dissimilar to you, Angela, for in those years I knew you toward the end of your life, your Pine Street studio, with attached bedroom, bathroom, and kitchen, was also your home. Certainly the Pateckys were anomalies within my home landscape of Tigard. My family knew no other practicing artists; their unfamiliar profession felt foreign. They had made art their life, made financial sacrifices, angered parents by their choices. Unlike you, Angela, who had the good fortune of supportive parents. You had known early on in your life what you wanted, and at fourteen you completed your first-ever sculpture. In a September 1918 letter to your father, serving in France during World War One, you wrote “I have decided to be a sculptor—how do you like that? I made up my mind long ago to be an artist & I think I will like that best of all.” Sculpting was an unconventional path for a woman born in 1903, an era when few women had careers, but you were determined. I recently read a book of letters that Blanche and Albert wrote to each other while he was away in New York, learned about their struggles, their commitment to a life of art. Blanche to Albert, March 1945: “My dad thinks we will never make a living with art in Portland. I told him if we can’t we will have to go where we can, that’s all.” Albert to Blanche, February 1945: “So Blanche, you must look ahead and enjoy nature and we will get along in life. What we need is wholesome, good, clean mental stimulation, sunshine and rest. Let us acquire those things first. Then we will build our bodies and fertilize our minds with stimulating thought and constructive enterprise. The money will come its own way as a reward for our efforts.” My Tigard friend Joyce, who also took piano from Blanche, recalls arriving for a lesson and seeing on an easel a painting of a bouquet of flowers. Behind the easel sat the real bouquet of fresh blooms, the ones just painted. This is not my memory, of course, but I am intrigued by the alchemy of artistic transformation, that move from vision to execution. Joyce’s recollection has spawned my curiosity: Was Blanche satisfied with her painting? Did she feel she had achieved her vision, that the painting had survived the transformation? In Art and Fear David Bayles and Ted Orland write that “a finished piece is, in effect, a test of correspondence between imagination and execution.” Did the painting pass that test for Blanche? What were the differences between the real bouquet and her painted image? Were the flowers from her own Tigard garden? I imagine her carefully picking each bloom for color and freshness, then arranging them artfully. Did she use oil or watercolor paints? If watercolor, there would be little opportunity for changes; the painting that Joyce saw would probably have been finished, the transformation complete. If oil, she could have much more easily returned to work on it again; even after the flowers had faded, the possibilities would still be open. You, Angela, as a young artist in Paris studying with French sculptor Antoine Bourdelle, witnessed this kind of transformation from reality into art when you watched him work on a clay model of a woman posing. Within that fertile and creative atmosphere of his Montparnasse studio, he narrated his motions, his artistic decisions as a lesson for you. Normally his wife, Cléopâtre, “was the only one allowed to stay in the room while he modeled because of the intense concentration required,” you told me. Watching Bourdelle work was a great privilege, the most exciting and educational experience of your three years in Paris. As a teenager in Tigard, I had soaked in the atmosphere of the Patecky studio. Under the gentle duress of my mother, I sat at the piano keys as an object of discipline and practice. But is that not the artist’s way? That combination of creativity and hard work? I began to absorb the creative worker’s way of life expressed in that studio, the examples of Blanche and Albert and Kenneth’s lives. This is the phenomenon of influence on a young person by adults, even if the young one is unaware of it, as certainly I was at the time, blurred by the hormones of adolescence. Only now, looking back, do I see what I learned, how I was changed. What is it about these artist studios? Do they speak to my own evolution as a human with long-ago ancestors who used red ochre paint to create images of hands pressed against the walls of caves? Reza Aslan writes in God: A Human History that “the oldest handprints go back some 39,000 years and can be found not only in Europe and Asia, but also in Australia, Borneo, Mexico, Peru, Argentina, the Saharan desert, and even the United States.” Ubiquitous. My human ancestors creating art. Even earlier than the oldest handprints, 100,000 years ago in Blombos Cave in southern Africa, humans “created an artist’s studio where they ground red ochre and stored it in the earliest known containers, made from abalone shells,” writes Heather Pringle in Scientific American. The purpose is unknown; perhaps to adorn bodies or clothing. A type of studio nonetheless. I can believe this inherently human impulse to create art in a protected space is what resonated with me in that Tigard studio, seeped into me and stayed. So that all those years later, when I was an adult and stepped into your studio off Pine Street, Angela, I was home. The Patecky studio in Tigard had once been foreign within the familiarity of my home landscape, yet that atmosphere of creativity became woven into the fibers of my memory. What had once been foreign to me in Oregon made your studio in Louisiana seem familiar, feel like home. And is this not what has happened to me over and over in my life as I have lived and traveled many places? The foreign becomes familiar until it feels like home. These two studios—both sheltered spaces for creating art—shaped my vision of self as creator, writer. Certainly part of my good fortune is to have a room in my Seattle home for writing, a protected space for my creativity. As Gaston Bachelard in Poetics of Space explains, “The house shelters daydreaming, the house protects the dreamer, the house allows one to dream in peace.” In reconsidering these studios in Tigard and New Orleans I have excavated an unrecognized dream: I crave a space full of windows and light; easels with paintings in progress; brushes corralled upside down, their bristles and tufts poking out of old porcelain vases; palettes smeared with colours like citrine, carmine, cerulean, fuchsia, celadon, imperial purple. I want, like Blanche, to make beautiful paintings of bouquets of flowers. I want, like you, Angela, to live surrounded by my art. Perhaps I will search for a light-filled space and take up brushes loaded with colour. Perhaps I will become a painter. Nancy Penrose

9 Comments

9/19/2018 01:52:38 pm

I read your piece, "The Bronze Crocodiles," in ZONE, a literary journal. Being from Louisiana I became even more intrigued.

Reply

2/9/2019 11:34:24 am

Thanks for reading my work, Paul Guillory, and for your kind words. As I write this in February 2019 I am in Louisiana again for events associated with the publication of the book Angela Gregory and I co-authored, A Dream and a Chisel.

Reply

Craig Fossati

9/22/2021 12:36:36 pm

Nancy, I have a wonderful Albert Patecky piece that was commissioned by my parents Norma and George Fossati when they built our first Milwaukie, Oregon home in 1954. It is a wonderful painting that I would like to share with you.

Christopher Belluschi

11/22/2018 06:55:05 pm

I stumbled upon pictures of Kenneth's sculptures in the Northwest Archives at Whitman College during my senior year there this past spring. I was quite taken by them, but had a difficult time learning more about him. Thank you for adding a personal conception of the artist whose works I am quite fond of. As I am now abroad in Madrid, your reflections on artists and their spaces gave me much to ponder as I look forward, and back, to the NW.

Reply

2/9/2019 11:37:15 am

Hi Christopher--Thanks for reading my piece that includes Ken Patecky. Glad what I wrote helped expand your understanding of his work. Enjoy your time in Madrid!

Reply

Jeremy Robinson

3/30/2021 04:36:35 pm

Hello, I just stumbled across your beautiful story. I have an oil painting by Albert Patecky that I have been trying to figure out its story and am writing you because, well, why not! It's a large oil that is not at all in the style for which he is best known. It captures a couple on wagon train burying someone along the way, with Mt. Hood looming large in the background. I love it! I wonder if there is any way or a direction you could point me in to, just perhaps, discover and save this paintings story? Thanks either way. P.S. I also have a little Blanche Patecky floral still life that I look at just a little differently after reading this, in a good way. So thank you for that as well.

Reply

Nancy L Penrose

4/1/2021 11:39:39 am

Hi Jeremy--Thanks for your message and for reading my essay! I am delighted to know you have an interest in the Pateckys and own two of their paintings. It's likely you have already found your way to this web page about Albert: www.oregonencyclopedia.org/articles/patecky_albert_1906_1994_/ Sadly, there is no equivalent webpage for Blanche. I do love her floral paintings! Also, a useful reference for me was this book about Albert that includes Blanche: Albert Patecky in New York: Letters Home from the Arts Students League, 1945. You might consider looking up their son, Kenneth, also an artist, who lives in the greater Portland area. Warm regards, Nancy

Reply

Craig Fossati

9/22/2021 12:40:13 pm

Jeremy, I have a wonderful Albert Patecky painting that my parents commissioned for the building of our first new home in Milwaukie, Oregon in 1954. I would love to see a photo of your large Patecky oil and would love to share my very mid-mod piece with you if you are interested.

Reply

9/22/2021 03:24:44 pm

Hey Craig Fossatti--I would love to see a photo of your Albert Patecky piece. Please contact me directly via my website at www.plumerose.net. Nancy Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|