|

At the National Gallery We mustn’t take the Old Masters too literally, the message always where you least expect it. for example, in Sassetta’s Wolf of Gubbio, our modern sensibility tends to focus on the bloody dismembered body of the wolf’s victim, how that contrasts with the saint’s friendly gesture, taking in his hand the appeased animal’s paw. But notice the four sets of heads among the merlons and crenels looking down, or the eight birds in flight forming a letter C in the empty space of sky in the middle distance, or coming out of the farther distant haze three large birds flying toward the scene. The message is not in the human faces, comprehending, pious, compassionate, nor in the sweet state conveyed by the saint’s forehead, brought out masterfully in the highlights-- there is a face looking up at something outside the picture-- not even in the shocked eyes of the face half-hidden behind the gorgeous red halo of the saint; all these-- someone is writing this down—all these still represent the human spectrum, the postures of our peopled selves, even the wolf must stand for some part of our selves-- a scribe seated on a bench with quill and inkwell in hand, the parchment unrolling down his crossed leg, Francis turning to him, gesturing, saying, “seal this pact in writing: the wolf here agrees to stop ravaging the people, and in return shall be fed at public expense.” Of course, what our eye fixes on are the severed limbs, a bloody leg cut off above the knee, another incomprehensible body part—like after a plane crash—and the partial bloody torso—wonderfully foreshortened. One may note how the graceful line of the saint’s arm, extended to take the wolf’s paw, continues along the profile of the beast’s head, enclosing the body parts cozily in a bowl-shaped space, but fail to see the ten trees of the grove through which the mountain road passes, that both the saint and the fellow behind him have five toes of the right foot and three toes of the left foot showing, that there are ten towers, very far, among the distant mountains. Stefano Petrizzo Stefano Petrizzo is an Italian-American poet living in the Sierra Foothills of Northern California where he facilitates a weekly workshop. He is the co-editor of The Day Barque and he holds an MFA in creative writing from Antioch University, Los Angeles. He is also a miller-baker making French style artisan breads in a wood-fired oven.

0 Comments

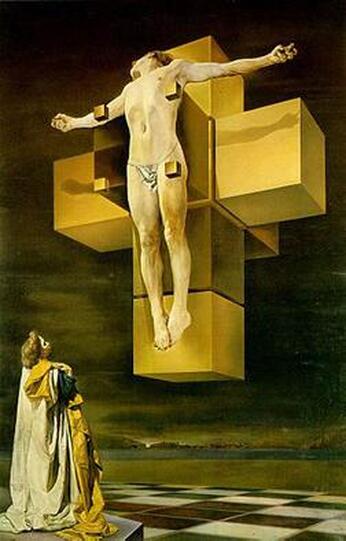

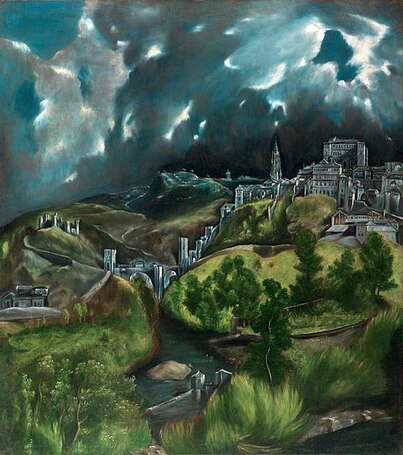

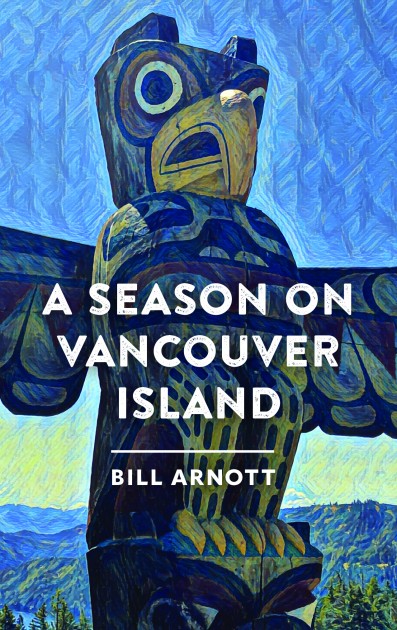

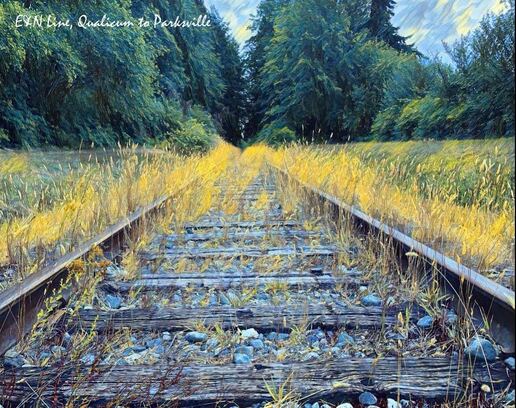

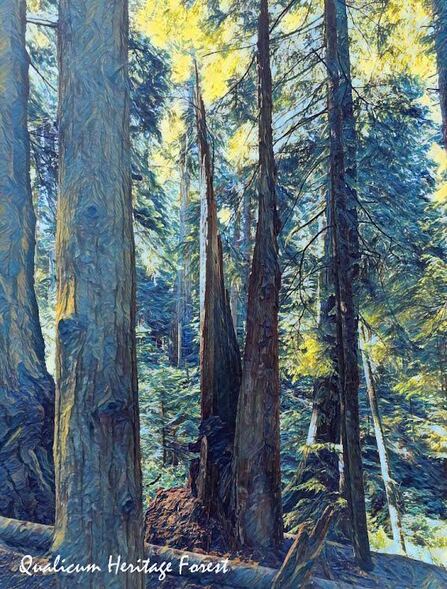

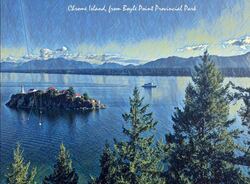

Landscape with the Fall of Icarus he obeyed his father practicing in rich air of birds and the bees skating over azure blue until water wet his feathers in fear and exultation he soared up into day to a pointless ending eaten by a hungry sun our dominion of just gods a plowman and a fisher tending field and ocean saw nothing of that fall a shepherd heard a cry only a partridge in the bush the youth melted to sea in bits of wax and wings gone and never noticed the sheep need minding earth feeds one thing to another PH Coleman PH Coleman came to writing after years of teaching chemistry in university and high school because, of course, poems are a molecular art. His work has been published in The Mountain Troubadour (VT), Eunoia Review, Trouvaille Review, Neologism Review, and in six ekphrastic exhibits in Columbia and Kansas City, Missouri. Souvenirs Before leaving the museum we were each allowed to buy a poster from the gift shop, not realizing that our choices that day would foreshadow the directions our lives would take for the next fifty years. Michael was twelve. He selected Salvador Dali’s Crucifixion. He will tell you that he was intrigued by the artist’s depiction of three-dimensional geometric forms free-floating on a two-dimensional canvas. I will tell you that he was excited by the prospect of the grownups telling him it was forbidden for Jewish kids to hang crucifixion posters on their bedroom walls so he could proclaim his inalienable right to self-expression and tell them they were fascists and so on but he was disappointed when the grownups said OK and paid for the poster and it went up on the wall without a fuss and he has spent the next fifty years trying to shock the grownups and occasionally he succeeds and some sucker takes the bait and exclaims “Oh my goodness, Michael, I can’t believe you said that” and his face lights up and he admits to being an irrepressible iconoclast. I was nine. I selected El Greco’s View of Toledo. I chose it just because I thought it was beautiful and I have spent the next fifty years finding beauty in places of darkness and foreboding. I have found beauty in the cubicles of my corporate day-job, in the stories of Franz Kafka, in the songs of Leonard Cohen, in the rhythms of the Mourner’s Kaddish, in women of self-destructive tendencies. I, too, have had a happy life. Pesach Rotem This was first published in arc. Pesach Rotem was born and raised in New York and now lives in Yodfat, Israel. He received his B.A. from Princeton University and his J.D. from St. John's University. His poem "Professor Hofstadter's Brain" was nominated for a Best of the Net Award. Interview with Bill Arnott: A Season on Vancouver Island Lorette at The Ekphrastic Review: You are well known for your wonderful, witty, award winning travel tales of the world. This book is a little different. Tell us about the way it came together, if you can – a bit about the how and the why. Bill Arnott: Thanks Lorette. It’s a privilege to join you again in the pages of The Ekphrastic Review, one of my favourite publications. Okay, the back story to my new memoir, A Season on Vancouver Island. I was vacationing on “The Island” and got together with my publisher at Rocky Mountain Books to chat Icelandic literature (as you do). We were planning a new edition of Gone Viking to complete my travelogue series as a trilogy in 2023. And I was asked if I’d also like to create a book about my current travels around Vancouver Island and British Columbia’s Gulf Islands and include original visual art. I’d intended to be there for a few weeks but loved the idea and decided to stay for three months, a full season. To do it properly I stayed in numerous communities across the “Big Island” as well as surrounding Gulf Islands, exploring, taking photos, and researching as I went. The result, I feel, is a rich, inclusive experience in yet another gorgeous part of the planet. Lorette: You’ve been everywhere, but feel your home area is one of the most magical places in the world. For our readers who have not experienced British Columbia, can you tell us what makes this place so special to you? Bill: While I’ve been fortunate to see a good chunk of the globe, I always stress you never have to leave to find beauty. There are wonderous things to discover wherever we are, in both nature and culture. BC’s islands and coasts are another example of this, with unique flora and fauna, outdoor activities, old growth forests, and millennia of Indigenous history and heritage, which simply can’t be overcommunicated. Lorette: Tell us about your photography, and the process of digital painting from your own works. Bill: For years I travelled without bothering to take photos, concerned I might “miss out” on experiencing something if I spent time looking at the world through a lens. Plus, I didn’t want the physical burden of a camera. But as tech improved I realized I could capture moments in a way I couldn’t always manage through journal notes or sketches. Image resolution’s not only great but opens up new veins of creativity, revealing subtleties I can miss in the moment with the naked eye. Now I find photos themselves a new canvas, at times calling for the addition of a supplementary voice, which I embrace with digital painting. This is the artwork that appears throughout A Season on Vancouver Island. What I do is incorporate a series of software applications to each photo, massaging each facet or colour-wash to achieve a stylized tone I feel enhances the storytelling and imagery. And as you know, multimedia invariably enriches an experience. Lorette: Your writing style is very vivid and imagistic – you really paint for us a picture of the places and events you are witnessing. How do you achieve that? Do you keep a notebook, or rely on snapshots? Do you write as you go? Do you research a place in advance, or after the fact? Bill: Thanks. It may sound obvious but I write what I like to read. My authorly mentors tend to write in a visually engaging, sensory manner, which I strive to incorporate in my work as well. Many of my favourite prose writers are poets too. That manner of crafting cadence, word play, and occasional dreaminess is a style I find evocative, inspiring, and a joy to share. Yes, I utilize journals for note-taking, while photos can serve as recollective touchstones and memory triggers. And I research destinations before, during, and after I travel there, as I find elements reveal themselves differently given those different perspectives – anticipation and a subsequent sense of familiarity. Lorette: Writing prose or poetry to correspond with your own artwork is a different experience from ekphrastic writing to another artist. Share with us what you learned about yourself from this process. Did you discover anything unexpected about your artwork? Did writing with your works in mind change your writing process or patterns? Did you feel your art and writing were complementary or competing with one another? How did the experience change you or change the way you work? Bill: Great questions. I feel it’s imperative that each element of the process, each medium, can stand alone, tell its own story and be the best composition it can be. I don’t necessarily see one thing – words or visual art – begetting the other, but instead complementary lines of storytelling creating a new elixir. I see it as a kind of alchemy. Like preparing a sumptuous meal. Start with exceptional ingredients. Keep it uncomplicated, take time, add your own flair and serve it with pride, knowing you’re sharing something truly special. When it’s sincere, authenticity shines through, making each presentation, I feel, extraordinary. And yes, the process of imagining, designing and creating A Season on Vancouver Island has changed me in a most positive way, deepening my artistic engagement and connection with readers who’ve not only come to trust my words but are now finding wonderfully new visual ebullience in our travels together. A Season on Vancouver Island by Bill Arnott https://rmbooks.com/book-author/bill-arnott/ RMB Books, 2022 Excerpts from Bill Arnott’s new memoir, A Season on Vancouver Island (RMBooks 2022) Introduction First things first. This is a part of the world that I love. Vancouver Island and its surrounding archipelago, British Columbia’s Gulf Islands, remain one of the planet’s most magical regions. When RMB publisher Don Gorman asked if I’d write a memoir about time spent here and include original visual art, not only was I delighted, but eager. Truth be told, I’d have created it anyway. Only now we can experience it together. Which is an incredible privilege, sharing vignettes and digitally painted photos, discovering new and familiar sites: forest, sea, the lands of Indigenous Nations. I’ve included a note as to names and transliteration, doing my best to accurately relay regional narratives. The result, I feel, is a time-bending present day journey, imagery of place and people, recollection of past while glimpsing the future. Meanwhile the star of this show, the Island, in fact each island and coast, continues to reveal remarkable, intimate secrets. It’s a sensory excursion I’m grateful and pleased to share. A season I hope enjoy. A feeling of departure, and possibility Ten thousand horses rumble to life. With a diesel vibration, water churns into chop and a blue and white ferry shoves us into the strait, in the direction of Vancouver Island. On the other side of the water, Nanaimo. Snuneymuxw. Coast Salish land. A sense of connection is what I feel, gazing through open steel portals. The horses pick up their pace, trot to canter, as a ripple ricochets through rivets and railings. The result, a feeling of departure, and possibility. It’s what I felt as a child, venturing into hills behind our home on a north arm of Okanagan Lake, bubbles of land carved by glaciers, the big lake fed by a narrow, deep creek. It was that sense of departing on a grand adventure that’s never gone away, each time I’m off somewhere new. Even places familiar, for that matter, seen for the first time again. As a kid I’d pick a stick from the deadwood, pry my way through barbed wire like a wrestler entering the ring, and climb. Over the hill cattle grazed, and the land beyond that was orchard. It always smelled dry. Of course, I’d take care, watching for cow pies, rattlesnakes, and undetonated mortars. An army camp was across the lake, and a few decades ago the arid grass banks served as target practice, bombs lobbed across the water. Now, aboard a westbound ferry, the day’s rolling out somewhat dreamily. The ferry is full, the first at capacity in months, and the crew’s a bit overwhelmed by an onslaught of passengers awaiting their Triple-O burgers, like kids released into summer following a particularly miserable winter. A winter that’s lasted two years. Our vehicle is on an upper deck berth aboard the MV Queen of Cowichan and we’ve chosen to stay put, hunkering in our well-worn car with the aroma of road trips, fast food, and bare feet. Meanwhile, Horseshoe Bay’s showing off its photogenic cliffs and arbutus, copper-pistachio peelings of bark as though they’ve been outdoors too long, overdue for a coating of sunscreen. Bowen Island rises from sun-dappled water like a child’s likeness of a surfacing whale, a round hump of a back, the only things missing being flukes and a blowhole waterspout. Sounds and smells mingle, wafting amidst cars: cell phone chatter, sneaky second-hand smoke, laughter, coffee, the vibrating basso of ferry engine, and the inevitable bleat of a car alarm, its owner nowhere to be found. Tatters of cloud stream past as we venture west by southwest. Midway across the Salish Sea we pass our doppelganger going the opposite way, the visual striking. A weather front’s hanging in place at the halfway point of the crossing, a vertical line of rain and smudgy dark cloud, monochrome seascape in a rinse of blue-grey. I watch the ferry pass through the wall of weather, easing from dark to light, like Dorothy stepping from blustery Kansas to the technicolour of Oz. Unbeknownst to me we’re making our very own leap through a time-bending lens, as we’ve come for five weeks, but will go home in three months from now.  Where The Chum Salmon Run A hummingbird that’s somehow familiar Packing for this excursion was simple. Deb and I threw an armload of clothes in a duffel along with trail shoes and a stack of new books. Our accommodation for now is a small cottage in the woods of Qualicum Beach, a copse of cedars keeping company with spruce, fir, and hemlock. The neighbours, we soon learn, are a family of warbling eagles, two owls who hoot hello, and a hummingbird that seems somehow familiar. There are songbirds as well: sparrows and chickadees, inverted wrens that nibble things from cedar strips, and a nondescript black and white bird with a monotone call and coquettish tail, the look of a folding fan. Getting here, we’d stopped at a highway service station on Nanoose First Nation land, featuring a Snaw Naw As gift shop. We bought a mug with a red bear design, creation of artist Jonathan Erickson of the Nak’azdli Band of the Gitksan Nation. Engraver and jewellery designer, Jon’s work incorporates Haida design, one of his influences being Tsimshian artist, Roy Henry Vickers. A second mug we picked up is adorned in hummingbirds, Indigenous design by Ben Houstie of the Heiltsuk Nation, also known as Bella Bella or Waglisla. Painter and carver, Ben’s work reminds me of pieces I found on Haida Gwaii. It was the first time I’d seen Indigenous design featuring hummingbirds, symbolic of beauty and love. Referred to as Sah Sen, the tiny bird is a sign of friendship and play, a messenger of joy, hinting at what’s to come. Crunching up a gravel drive through the corridor of trees, our temporary home resembles a fairy tale, and I keep an eye out for red-hooded girls and cross-dressing wolves. The little woodland abode has a fuchsia pink door, flowers in windowsill pots and a shiny red barbeque that must be brand new. This accommodation’s a pendulum swing from camping when I was a kid. One of our favourite destinations was a cabin, high in the hills in southcentral BC, Interior Salish land. We fished for deep water trout, which we smoked, and slept to the snap of mousetraps. Here, from our pink-doored cottage, we can stroll to the seaside of Qualicum, what original inhabitants knew as the place where the chum salmon run. The shoreline stretches northwest and southeast in a wide, gentle curve. At low tide, morning sun glints on ribbons of kelp in pink, ivory, and Celtic shades of green. Further south is Parksville and beyond that, Nanaimo, where our ferry arrived from the mainland. A string of seaside communities lies to the north: Qualicum Bay, Fanny Bay, Union Bay and Royston. Beyond the inlet, islands sit like a hand of cards: Denman, Hornby and Lasqueti, with Texada adrift from the pack, as though discarded. The tide moves a long way here, leaving a broad swath of beach. High tides offer good swimming, the water particularly warm now in the midst of record-breaking heat. Low tide reveals soft and walkable sand, the kind that demands you take shoes off and move slowly. Sun bakes exposed beach at low tide and then, as tide rises, heated sand warms the water. As a local explained, “It’s a swimming pool, with a tide.” A steep set of stairs, about eight storeys worth, connects a bend in the road to the beachside and makes for a good workout with ocean views. A tiny lending library, painted in rainbow colours, sits atop the stairs, where an abacus helps stair-climbers keep track of their reps. “I’m blue,” a woman explains by the abacus, as she tackles the stairs. Which doesn’t mean that she’s glum, but she’s using the blue line of counter beads. Today I’m yellow. Not sure why but it feels fitting. Perhaps a sunny disposition. Directly overhead, a bald eagle circles, casting a shadow with each pass while a crow makes a fuss, buzzing the big bird in flight. Following a few sets of stairs, I throw myself into the sea, and as I bob in the water a seal swims up and gives me the eye, but keeps a respectable distance, as though taking care not to spook me. Bill Arnott About the Author: Bill Arnott is the bestselling author of Gone Viking: A Travel Saga, Gone Viking II: Beyond Boundaries, and A Season on Vancouver Island. He’s been awarded by the ABF International Book Awards, Firebird Book Awards, Whistler Book Awards, received The Miramichi Reader’s Very Best Book Award for nonfiction, and for his expeditions Bill’s been granted a Fellowship at London’s Royal Geographical Society. When not trekking the globe with a small pack and journal, or showing off cooking skills as a culinary school dropout, Bill can be found on Canada’s west coast, making music and friends. @billarnott_aps Thinking Inside the Box- a Long Awaited Labour of Love from Portly Bard and Lorette C. Luzajic8/27/2022 Dear Readers and Writers,

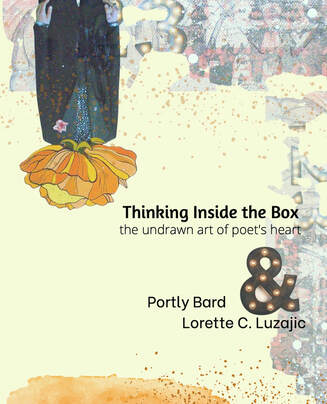

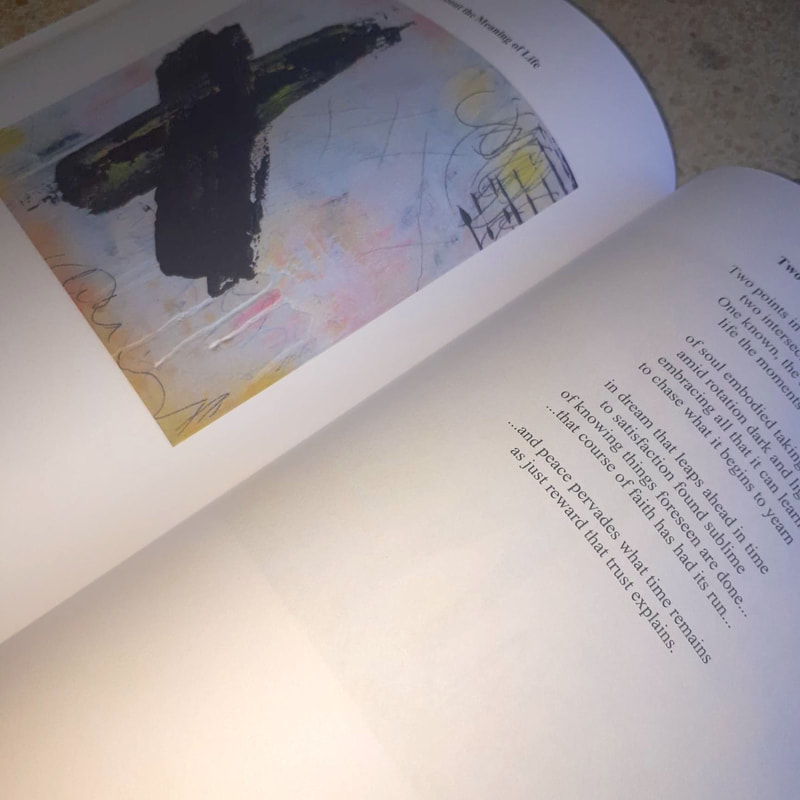

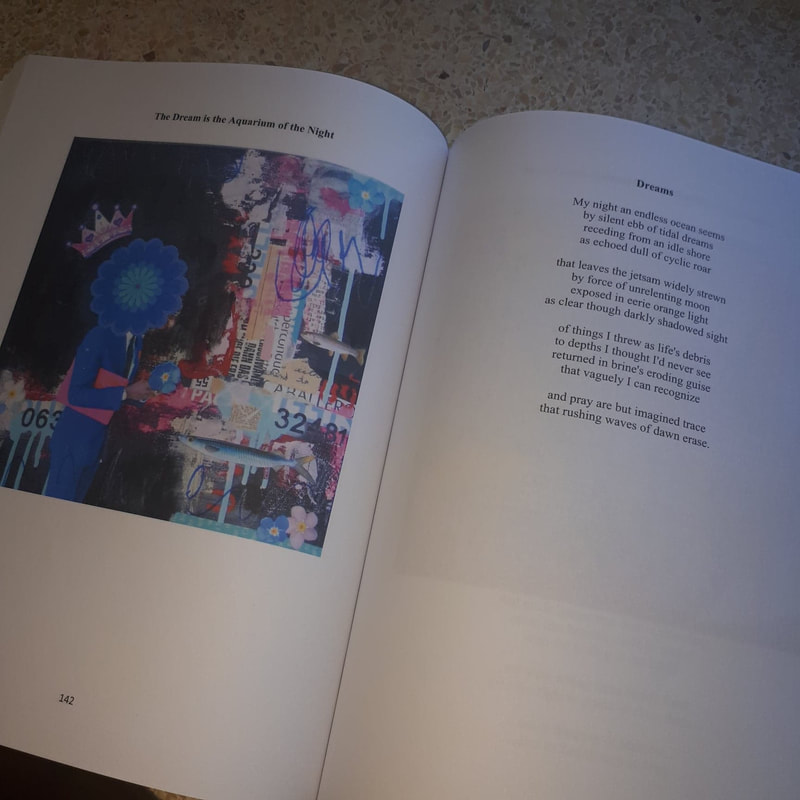

It it my great pride and joy to announce to you the birth of Thinking Inside the Box: the Undrawn Art of Poet's Heart, with Portly Bard. Longtime contributor Portly Bard has spent several years working on a major collection of poems inspired by my visual art collage painting series of signature squares. We have been working hard behind the scenes for some time to put this collection of poetry and full colour art together. It is now available in a trade paperback, 324 pages, 8x10", full colour, for $32 USD. There are many upwards of 100 artworks and accompanying poems, along with an essay by Portly about his journey into the maze of my mixed media artworks, my response, and a back and forth dialogue about ekphrasis and art. I adore the contrast between our voices. Portly Bard writes in traditional metred rhyme, and my artwork is a collage of modern urban narratives, including abstract, graffiti, expressionism, surrealism and pop art. Yet we meet somehow in the centre from opposite ends of the spectrum, and Portly's poetry holds uncanny insights into my work. He manages to put into words what I am not able to explain myself. We have done our best to keep the price reasonable while offering a colour print edition. There is a PDF digital version to keep a lower price option available, or for those who don't want to use Amazon. It is $10 CAD or approximately $7 USD. If anyone hopes to have a copy of this material but cannot pay, please send a note to [email protected] and ask for your complimentary digital file. All proceeds from this collection go directly to support The Ekphrastic Review. Click here or on front cover image above to view or purchase on Amazon. Click file below to purchase PDF copy. Dear Portly Bard, I cannot thank you enough for this moment. Thank you to all of our readers and writers for building this ekphrastic world with me. Our family is world wide and growing and the joy of ekphrasis is blooming everywhere! love, Lorette My Mother Contributes to Force and Reaction Not my bird’s nest, she said to the young real estate agent on an errand for an unnamed buyer, sun tanning her skin as she reclined with an issue of Vogue or Time on her deck in the small town named for a Celtic paradise for the knights of the roundtable. No one else was there, and besides, it was her decision, the house in her name. Just that weekend when we were all there, flocks of tired and talkative passerines had lined the telephone wires, roof edge, deck railings and shrub pine tips to change feathers. House sparrows, marsh wrens, pine siskins? Could hardly see out to the brushstroke sea in its dark September hue, its arching olive and ruffling salt breakers. Vulnerable, she was, but in the future tense, not with this messenger her nephew’s age. Nestled in the peaceful Tuesday, with gusts scattering things months away, she’d not meant to receive anyone in her bathing suit, though it had its own skirt, a delicate wave of Lycra below her waist fluttering free of its modus to stretch. She was not like the rest of us who actually body surfed the coastal Atlantic, but she did like negative ions lifting the mood. What music was playing? Not Donna Summer’s heavy breathing wafting over the dunes to the neighbors in the years that was embarrassing. Maybe Anne Murray, Willie Nelson, Django Reinhardt spinning on my old high school stereo, the future tense of which was a stylus needle in a melted plastic shell. That refusal to let go of something someone else wanted — beachfront property, not the graying brown mid-c mod built on the sand like a plus sign — brought a gale force wind to our lives, disheveling it and leaving it that way, as we dispersed from the ash. How was it that she had no right in what was hers? The next migration birds arrived to moult on the kinesis of invisible house reduced to kindling. Amy Holman Amy Holman is a poet, literary consultant and artist. The author of five poetry books, including the prizewinning chapbook, Wait for Me, I’m Gone, from Dream Horse Press, and the collection, Wrens Fly Through This Opened Window, from Somondoco Press, her poems have recently appeared in The 5-2: Crime Poetry Weekly, The Chiron Review, and The Night Heron Barks. Join us this coming Sunday afternoon for our ekphrastic Sunday Session.

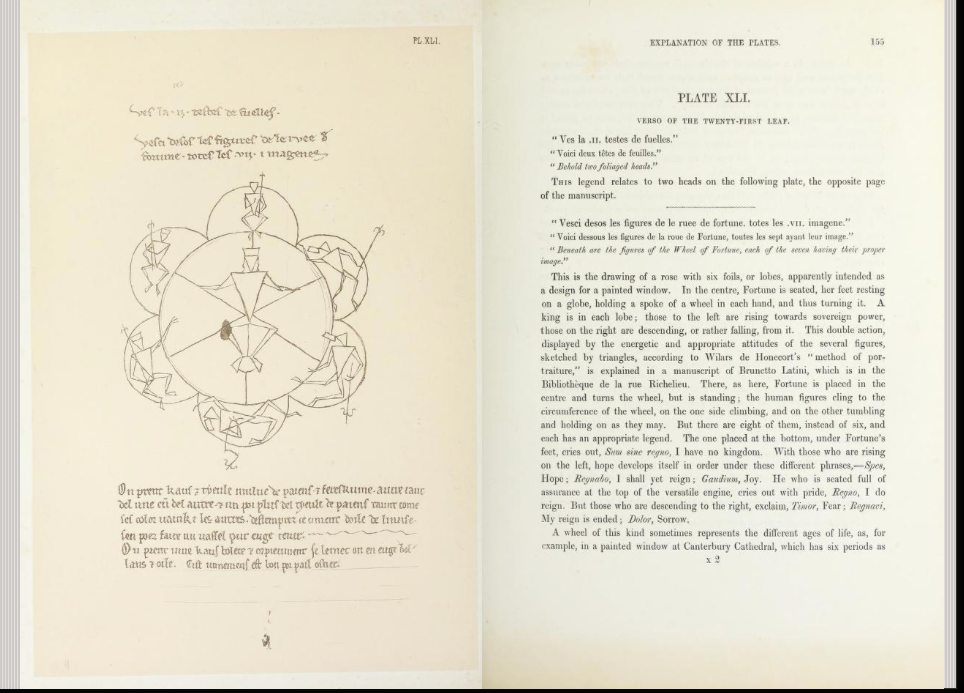

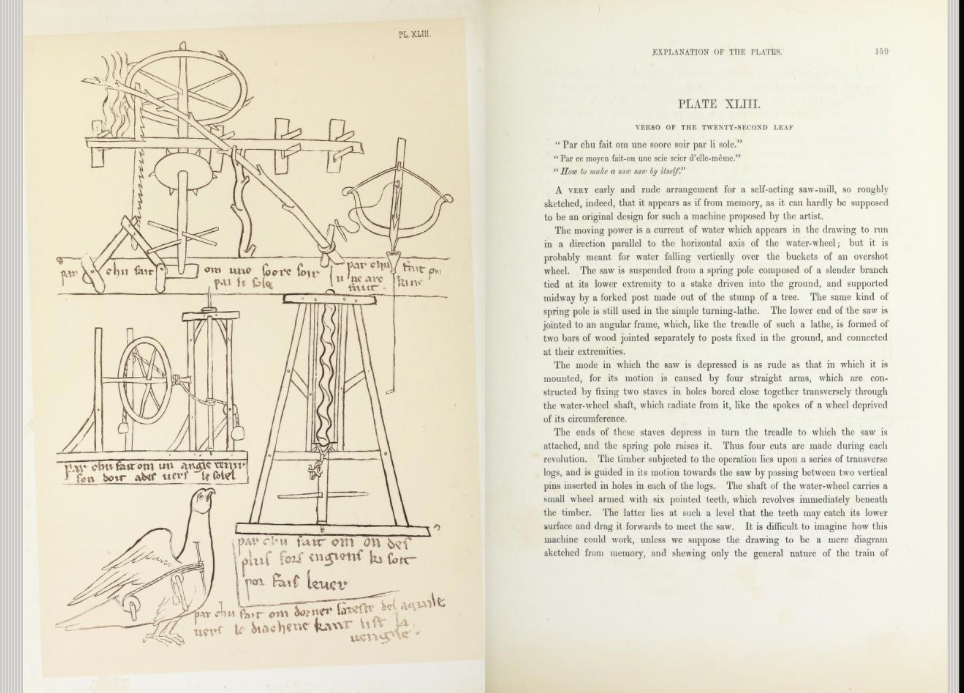

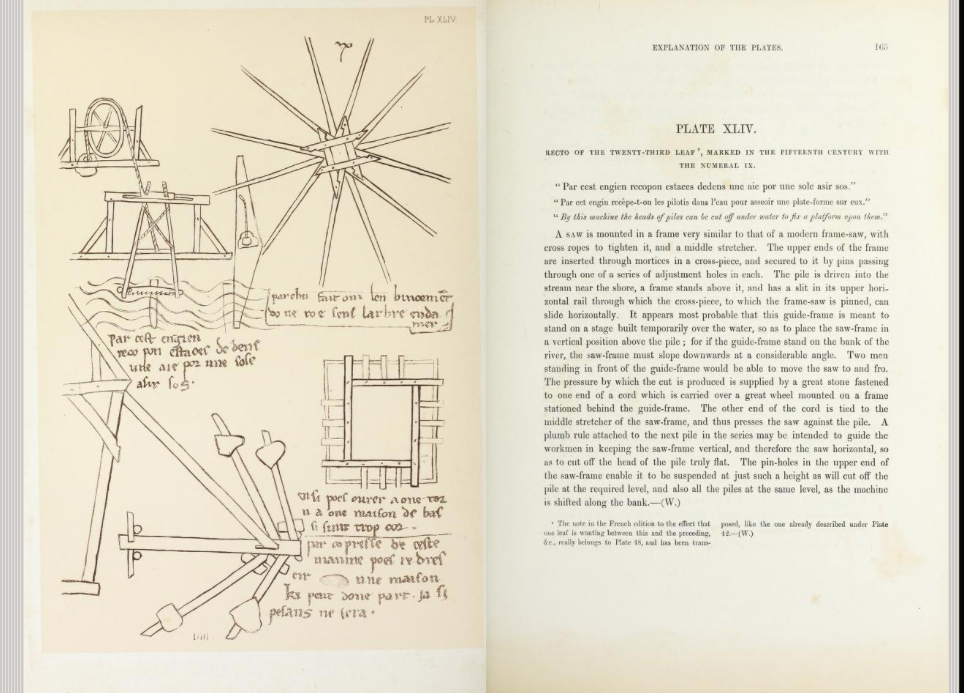

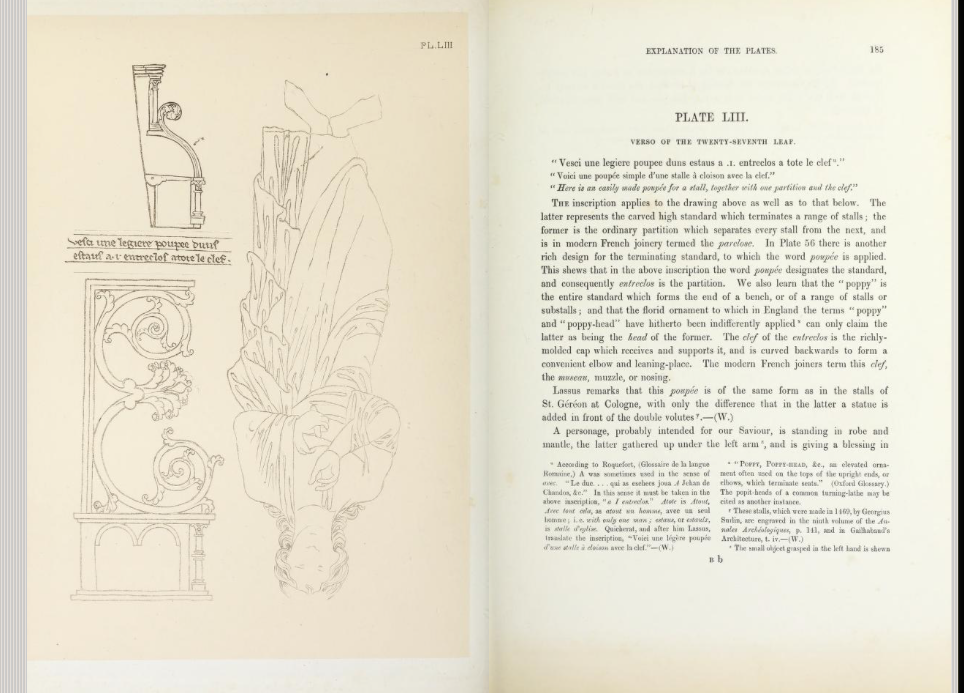

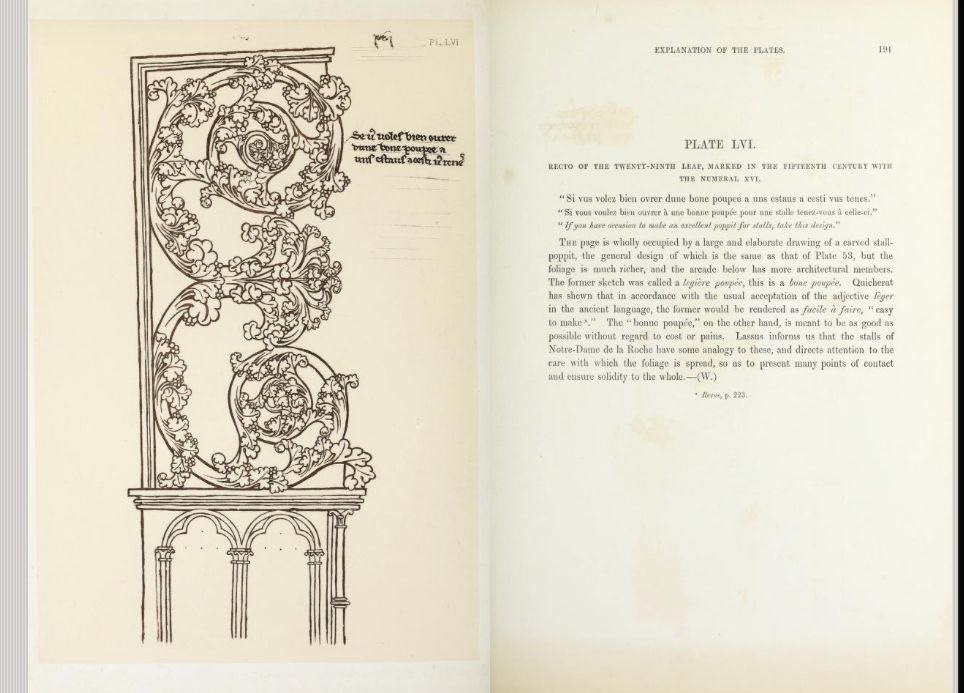

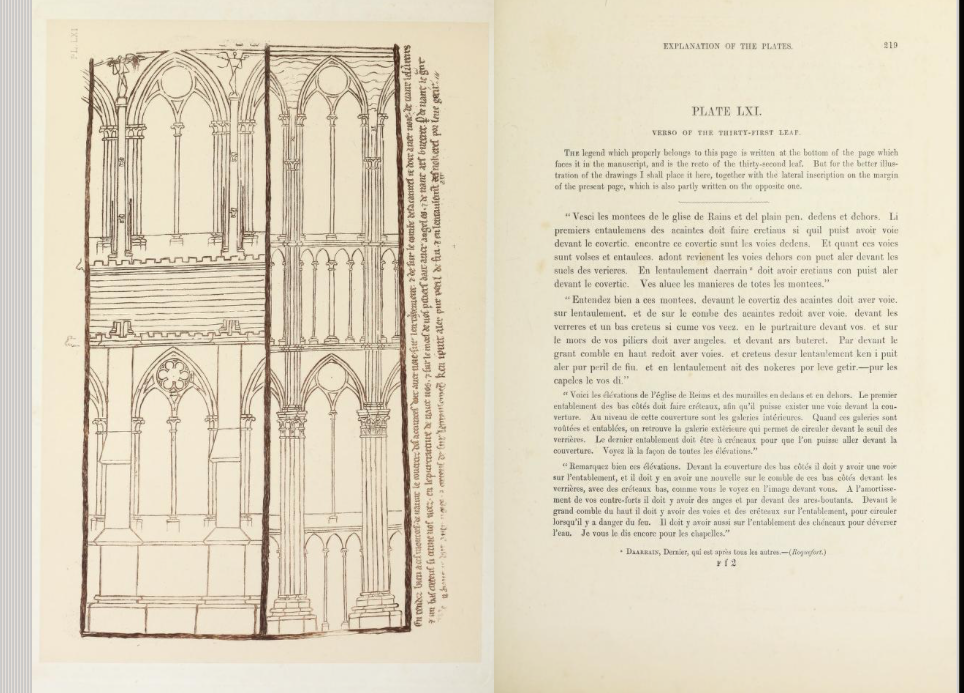

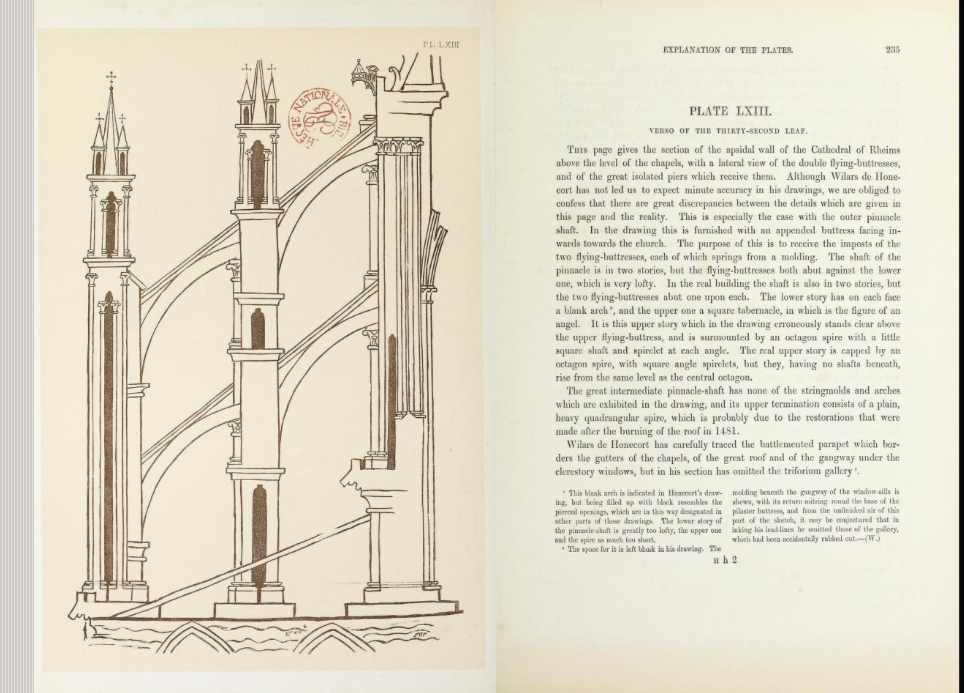

The Sunday Sessions are single event zoom workshops where we get together to explore art and write. In these sessions, we explore and discuss four or five different paintings, and do writing exercises from the themes and imagery in the artworks. These sessions are informative, fun, and creative. We connect through conversation, writing, and optional sharing of the sparks we produce. Other upcoming workshops include a session on Joseph Cornell, and on the witch in art history. Check them out here. All are welcome! These workshops are a great fit for both experienced writers and new ones, because we use different approaches to inspire a variety of responses. Poetry, fiction and prose writers welcome. Some writers leave with new drafts, new blueprints, or simply with new sparks and ideas. Only two graphic documents survive to tell us about architectural design in the Romanesque period of church architecture: the 9th-century plan for the monastic complex at St.-Gall and the 13th-century sketchbook/portfolio of Villard de Honnecourt. The sketchbook comprises 33 leaves in various bound booklets gathered together in a leather binding. Villard left about 250 drawings of architecture, sculpture, nature, and technology along with comments about almost all of them. The portfolio describes what Villard saw but offers us very little description of Villard himself. A facsimile of a study of the Sketchbook is available at: https://archive.org/details/facsimileofsketc00vill/mode/2up 21 verso Fortune sits at the center of six spokes, the world at her feet as she turns the wheel. On her right, three figures ascend toward power, imagining themselves destined to be sovereign, powerful, enthroned, seated above Fortune, having conquered her. On Fortune’s left, three figures fall from grace, dragged under and around the wheel feet first, useless scepter in hand, eventually crumpling as the figure is ground under the wheel. Seven figures, but only Fortune is anchored. When the secular wheel of fortune blooms into a cathedral rose window with petal-lobes around an oculus, then, for purposes of faith, Fortune may be replaced by Christ, who is also set for the rising and falling of many. 22 verso and 23 recto Dreams of spires touching the sky and canyon- like naves and vaults that arch like the bowl of the Genesis firmament were pipe dreams until the incarnation of mechanics and technology that allowed for the music and poetry of cathedrals. A frame saw for cutting stone. A saw that saws by itself. A guide to attach spokes to a wheel a wheel that uses a system of pulleys to raise stone high in the air. Stone fulcrum and lever to raise a sleeper beam until the lever has reached its highest potential whereupon it is wedged up, the fulcrum relocated, and the process begins again. It was not enough to create temples in the imagination. Instead, imagine the cathedral, then innovate until stone and wood became levers and fulcrums and scaffolding and wheels that could create stone walls and wooden trussed roofs and round windows. Without pulleys there would be no clerestories. But there would be neither pulleys nor clerestories without the intention to build to the glory of God. 27 verso and 29 recto In worship, clergy and choir sit, kneel, stand for prayer and chant each in a separate seat, a choir stall. Side by side, habit by habit, a row -- maybe rows -- of duplicate vestments making indistinguishable people, separated from the congregation by the end of the row of stalls. How much is that separation worth to you? Villard first sketched Une legiere poupee :easily made: facile, in fact. An end for a row of stalls outwardly curved wood with a swirl of leaves. A tiny capital at the top beneath a multilayered cornice. Simple. Easy to make. Easy to separate Two leaves later and simple has become une bone poupee. A poppit – stall end – that is bone, that is, bonne. Not just good, but :as good as possible: Mirroring spirals swirl out -- no regard for straight wood grain. Covered in leaves, the two swirls touch and spring out: a fountain of leaves with branches. Villard directs: "Si vus volez bien ovrer dune bone poupee a uns estaus a cesti vus tenes." :If you have occasion to make an excellent poppit for stalls, take this design: Pay no mind to the cost in money or in labour. Separation between clergy and congregation is worth any cost. 31 verso Variations on a theme: hoops or circles over two Gothic lancets From the outside buttresses -- too close to see them fly -- from the inside blind arcade three arches. Proportions are key -- How much lancet? What size circle? How many columns? What is too narrow? 1:3 was golden: height to width. Divine. 32 verso It is as if they stand -- three stalwarts -- backs entirely straight feet shoulder-width apart heads up eyes forward one arm extended touching the shoulder of the one standing nearest fingertips barely touching that one’s shoulder in order to keep adequate and constant distance between them. And, actually, it isn’t ‘as if’. That is what they are doing. Lynn Miller Lynn Miller is a candidate for the MFA in Creative Writing at Mississippi University for Women. Her education and employment live at the intersection of art, faith, and education. She has served at various times in her life as a museum educator, a pastor, a freelance artist, and an art educator.

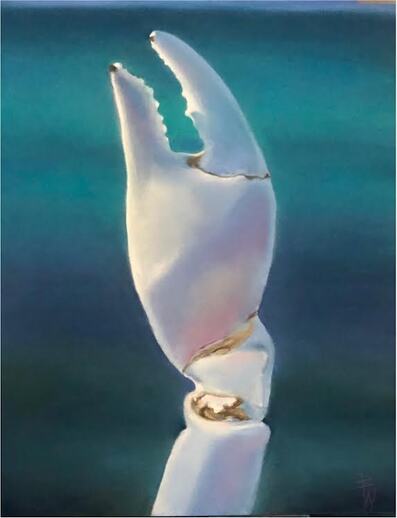

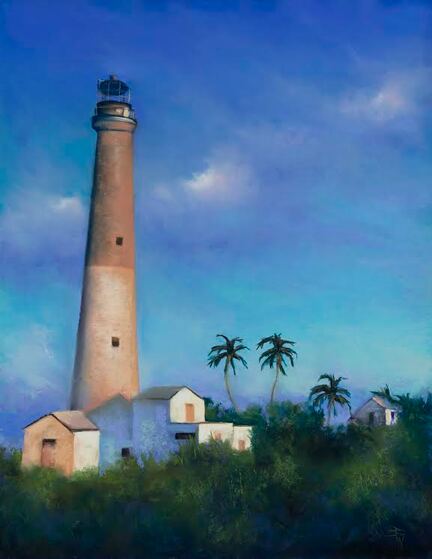

In 2019 my mother, artist Beth Tockey Williams, and I completed a collaborative Artist Residency for the Dry Tortugas National Park. We chased the rainbands of Hurricane Dorian down the coast of Florida, then took a four-hour ferry to Garden Key. We packed in our food, art supplies, and books, and spent three weeks living and working off the grid on Loggerhead Key. This residency allowed us to reconnect after years of separation when I had completed my studies, but also gave us time to remember why we create art in the first place. The death of my brother and our decade long search for solace guided us again and again to art and poetry, nature and empathy. Alone on this abandoned paradise, we were confronted with the harsh realities of climate change, ocean pollution, rapidly spreading coral disease, invasive species, and an apathetic administration. We wanted our final ekphrastic collection to highlight the beauty of the Dry Tortugas and the necessity of protecting our oceans, while also reminding us of the transformative connection between grief and nature. Hailey Williams Reunion I pull from tangled island ventricles pale claws nearly dust to stash in my breast pocket. Clittering china, I picture a family of crab ghosts converging over my pulse, ready to tuck into their first bloody meal after death; eye stalks sway in synchrony raised in prayer to Sea, or perhaps his brother, Sky. Spectres Crustacea mingling in my pocket, I scoop out my heart and permit you to feast. Calypso’s Five Decade Soak 1. Soap suds storm porcelain edges of the Gulf of Mexico, making landfall at record speeds. We leave the water on, think she’ll turn it off herself. 2. Freckled & bruised, a soft island – Calypso’s breast emergent in the wide bath. Reef-ribbed, polyp-pored, kelp-curled, skin flakes off in salts and sands. How long can she hold her breath? 3. When our tub overflows her sand-bar knees submerge. Next the fortified elbows, her lighthouse nose, colorful Keys adorning her toes. 4. Plastic baubles swirl & organs bleach, skin peels off in scutes, her hard-bright room sings like a goblet as the waters rise. 5. An inch a year, soon a foot, a meter, three. Our Calypso lulled by heat, drowns. Her heart? Brined in its own salts. Still we do not stop the faucet. Lightning is Dead Then thunder comes on shoulders of rain. The roar you think will taper off so you stop to hear her out; on she shakes & on. Her bellow beats bereft the balding palm, prickle pears wag paddles in her face. You hear her grief-ripples from the thick-aired house, windows agape, sills – tongues for puddling. She sobs through lunch of jasmine rice & coconut milk, sobs through day marking papers in blue-black strokes. Even unto sleep, even once rain has ceased, thunder crawls down the dark hall on her hands & knees. Fledge The sea grape’s many ears are broad and full of mirth – petite wax cups steeped in adoration of each skim and sweep of the young sooty tern, his scoop of tail, sea-shine on dark wing. No wonder she raises her round ears to the storm. No wonder she lets them flutter and fold and perhaps, one day, tear free. Letter to a Ghost Is it you rustling spider lilies, observing gull-court on the rotten dock? When I walk to Loggerhead Light to record solar data, do you round our hammock, or wind or green coconuts? Are you there (I want to know) as I skim waves over yellow reef, hunkered down between brains spinning tales to sea fans? Is it really you stepping bright between my dreams or just lightning on the channel? Does your hand reach over sea oats, do your long blue fingers carry the scarce rain? Are noddies your emissaries or moon jellyfish who haunt me much like you do? Is it your hum when I kiss my ear to conchs, pink and bony fists I hold like your hand. You plant messaged bottles for me in the sand. Will I have to die before I can reply? Floating You haven’t met my mother until you find her sun-pickled blonde, salt-skin thigh deep in waves, streaks of pastel dust on her face exhaling sea pigments with the wind. You haven’t heard my mother’s voice, woodsy and cantering, unless it sunders sky: cúmulo, cirrus, oranger than you’d think when sun splits horizon or the new moon rises over a deepening white-capped iris. I never knew my mother’s first self who navigated starlessly. Still, I see the child of her sometimes; eyes closed she hangs between the waves each day her toes touch less and less. Wave Unfathomed foam-limbed one, arouse long-hushed aches – an eye, a laugh, the up-curled lip – those many features scattered, now resound undying against these shores. One thousand times you’ve paused here, yet here again you stretch exhaled upon the strand, but rush away as in regret. Yes, regret like glass shards within you, little wave, little ocean cold and broken. Loose forth again your grief – those soft-scruffed palms like keyhole sand dollars, fingers sprawling fascinate whelk dainties; you gave so generously. I miss them too, those hands, the splash of them, castle-builders. They would have grown, you know, lengthened like spiny lobsters. Your love was caught, I see it in you. As was mine. I’ve wrecked once more, and though they may not be as long, I give to you these hands. Wading in the Afterlife Have you held the curve of a place in hand? Still as a sea urchin’s sun-decay, skeleton then sand. Spurring the silent primal sense that creates the weight of a place – its ghosts. Have you come to love the atoll ghost? Have you learned its gin-green curve, witnessed the coconut bite down to create in time the freckled palm – never-still? Traipsing in island brush, sand spurs self-harvest on ankles deep in decay. Have you thought much of your own decay? Such disintegration! Then, the formation of your ghost. Do you yearn to linger in the winds, or do you spurn all cares for death and its delights, its curve into the dark? Spilling sands one day still, but in their spill islands diminish then re-create. Drift along and in your mind create a place with joy in the decay, you’ll reach that coast and see the moon still heaves itself from the deep to call each ghost by name and let them thrill along its crater-curves. You don’t believe in ghosts? Nor spurts of death-light, nor bleached bone dances? Spurious is poetry, the superstitions it creates. You forget the taste of horizon curved in hand. You forget the mute corals, who decay long after light has left and leave staghorn ghosts dancing bones through shallows still. Have you gone to a place to be still? Have you opened your hand to the spur of crab claw, to the spindling ghost in decommissioned lighthouse, to the creatures living an instant in amorous decay? Have you let the world open you and curve, curve along your spine like water distilled? Give in to the decadent, the spurious, for even as I write, the hot sea creates new ghosts. Hailey Williams “Fledge” has been published in Humana Obscura, “Reunion” was just included in I Am a Furious Wish: Anthology of Lowcountry Poets Vol. 1, and “Calypso’s Five Decade Soak” is forthcoming in Surge: The Lowcountry Climate Magazine issue 2. Hailey “Pell” Williams is an MFA candidate in Poetry and Arts Management at the College of Charleston, and an editor at Surge: The Lowcountry Climate Magazine.Hailey’s work is forthcoming or published in the Birmingham Poetry Review, and Humana Obscura, among others. Find more of her work at pellwrites.wordpress.com Beth Tockey Williams recently achieved her Master Circle Status with the International Association of Pastel Societies. Her work has been featured in The Pastel Journal, Charleston Living, and Charleston Garden and Gun Jubilee, among others. Find more of her work at bethwilliamspastels.squarespace.com On the Lookout for my dead wife, I wait. Nicoline, coming in on a Viking galley, escaped from that Valhalla encampment breaking the horizon. Barely, I see her on deck, blonde bubble braid twisting in the wind, while she bolsters the bow, warrior-woman escaped to return, one foot planted on the prow, a vascular forearm across her breasts, like a Norse shield. She has forsaken Odin for her lost love, ready to reign again alongside me on this Lookout Throne, ready to crest any wave, no matter its undertow. What do they want, these pot-hatted lay-abouts lining the sea’s lip, each a beached walrus? They await the salmon boats, that’s what they want—the fish, the smell of the fish, taste, the money for the fish, the cold aquavit before and after the fish boil. Their lives are full bellies, sand filled clog boots, and a knock on the door at midnight. Mike Lewis-Beck Mike Lewis-Beck writes from Iowa City. He has pieces in American Journal of Poetry, Apalachee Review, Blue Collar Review, Cortland Review, Chariton Review, Eastern Iowa Review, Ekphrastic Review, Guesthouse, Heavy Feather Review, Inquisitive Eater, Pilgrimage, Pennine Platform, Southword, and Wapsipinicon Almanac, among other venues. He has a book of poems, Rural Routes, published by Alexandria Quarterly. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|