|

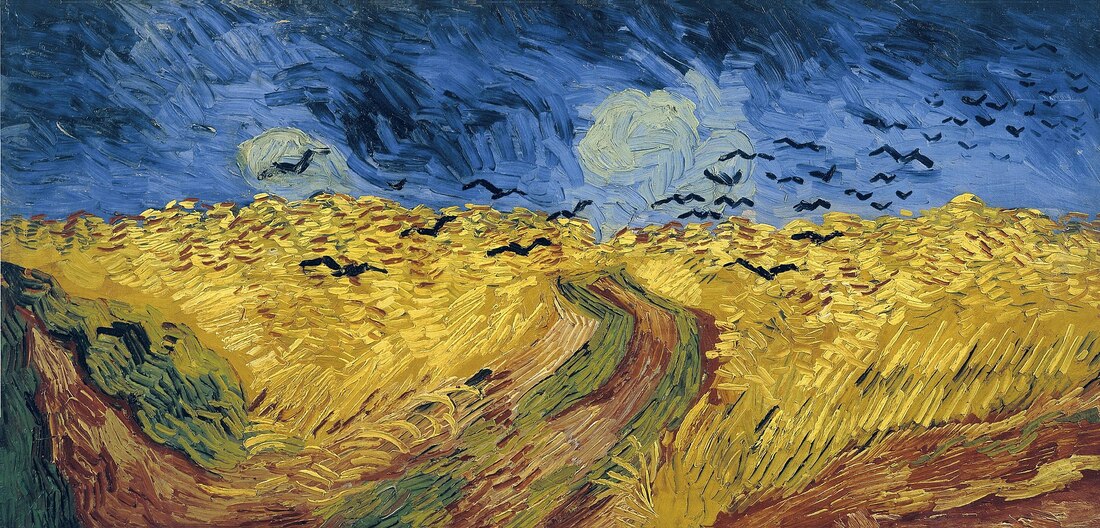

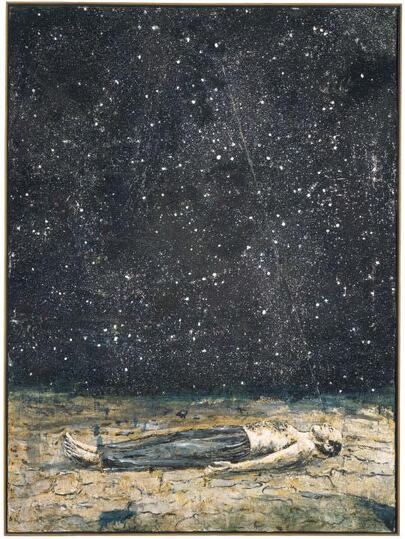

On Seeing a Stranger Witness Wheatfield With Crows It was a Friday when I first saw you, frozen into a past I’ll never know, like one of his models, worn down into the clay of earth, a haystack robbed of sound, a swallow in a rainstorm. The painting is of course, beautiful, but what I remember is you, staring at Van Gogh’s wheat fields, the strands of your hair pulled back, rows of maize, straying fields of willows. arteries of dark clouds undulating in that hidden air. You were sobbing at the weight of bearing witness to the quiet of a coming storm. No artist will ever paint my mother, who looked the way you did when she let a phone fall from her hand like water after the hospital called. I didn’t know art has everything to do with the weather, how close it can come to the surface. A storm tears asunder. A flock of crows flies south. Robert Walicki Robert Walicki's work has appeared in a number of journals including Fourth River, Uppagus, Vox Populi, and Chiron Review. He currently has two chapbooks published: A Room Full of Trees (Red Bird Chapbooks, 2014) and The Almost Sound of Snow Falling (Night Ballet Press, 2015), which was nominated to the 2016 New York Showcase of Books at The Poet's House in NY. His first full-length collection of poems is Black Angels (Six Gallery Press, 2019) and his latest book, Fountain, was just released from Main Street Rag Press.

0 Comments

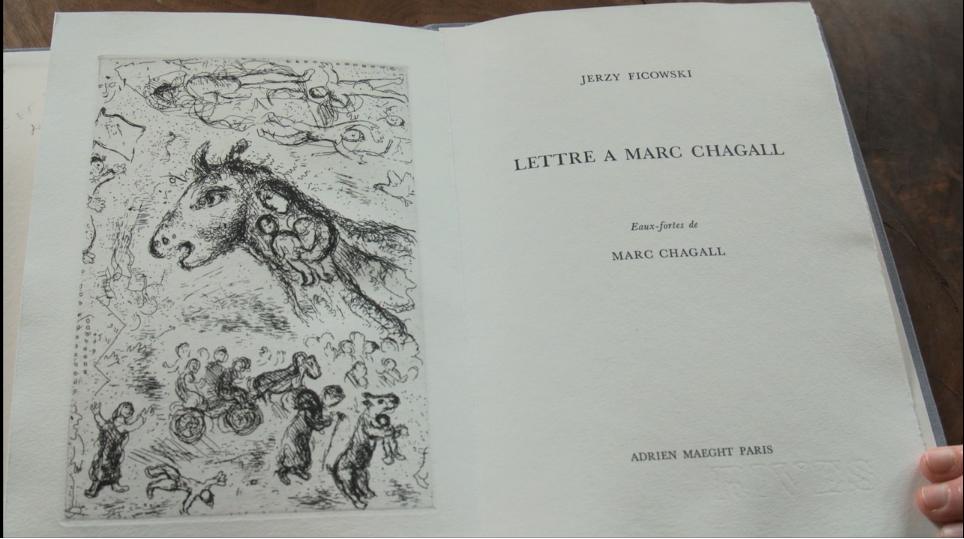

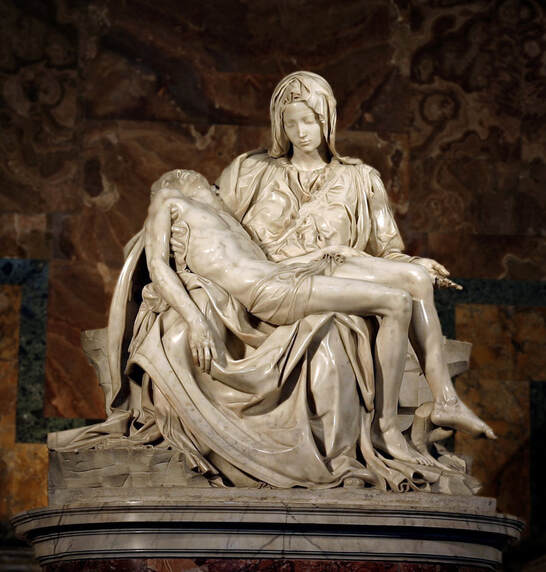

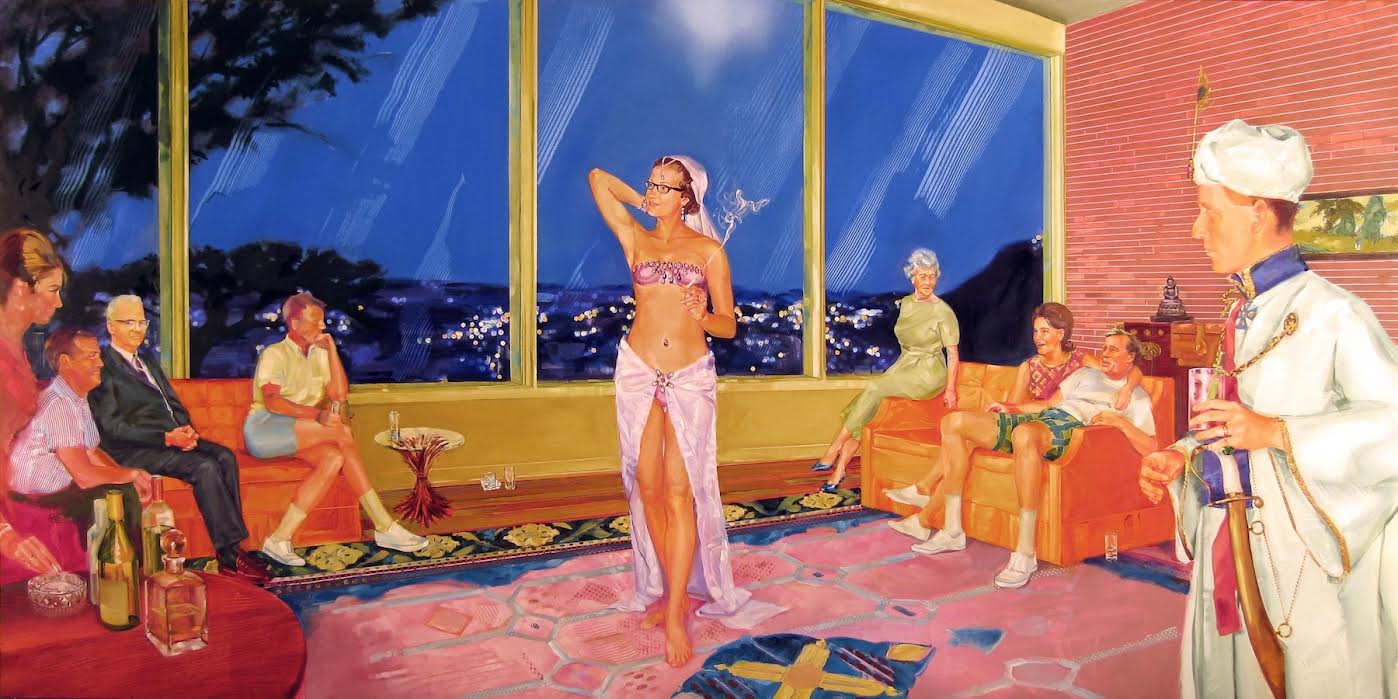

Please follow the link to Vimeo below for an important 15-minute video documentary made by physician and filmmaker Michael Nevins. It’s about an ekphrastic holocaust poem by Jerzy Ficowski, inspired by Marc Chagall’s paintings. The poem led the artist to do a series of etchings based on the ekphrastic, which in turn inspired the film. Thank you to poet Brian Kates for the suggestion and connection with Michael Nevins. Thank you to Michael Nevins for sharing this work with us. Thank you to Vera Aronow of Turnstone Productions for helping to make this possible. This is an important documentary for ekphrasis, art history, and history itself. We hope you will follow the link and enter the password to watch it. The password will be good for six months only. Letter to Marc Chagall https://vimeo.com/789862823 Password: Chagall2 From the Plains The day began with a nor wester, storms expected by nightfall. The wind blew wildly as if you could soon be the last person on the planet. Blinds rattled. Doors slammed. People of the plains fear what can’t be seen. Clouds brightened to red changing, changing. On the veranda, I painted a blanket of land and sky to wrap about me to sleep inside till dawn. What Trees Remember Holding their space in the forest, trees remember starlight filtering to warm, dark earth and the sound of the violin before the violin was made. Bark gathering moss, trees recall giant birds flying from mountains and songs made by fluttering wings as birds built their nests. Touching branch to branch, trees share stories of sailing ships their ancestors held inside before the world became a globe. Books and newspapers come and go. Trees think back to when the first seed split. The Empty Seat Our walks beside water, punctuated by gnarled sticks and steep steps took us above thoughts we carried, across long grass to where we could read beyond the story so far, the history of bodies and bones. Who was it, we asked, who made this place? But not on the first visit, not right away. Repeated, the walk became a ritual something known, but still holding mysteries like a quest. The last time we got as far as the seat we saw its frame clasped to sky and cloud, sniffed in the breeze the season changing. Michael Mintrom Michael Mintrom is from Aotearoa New Zealand and lives in Australia. His poems have appeared in various literary journals in those two countries, such as Landfall, Meanjin, Meniscus, takahē and Westerly. Other recent work can be found in The Drabble, The Ekphrastic Review, Literary Yard, The Metaworker, Quarterly Literary Review Singapore, and Shot Glass Journal. Mother, God I am alone in the hush of St. Peter’s, tour groups circle like pods of killer whales hungry for experience. Three nuns float by in unearthly robes. I turn and there you are-- icon of high school art history-- iceberg madonna, luminous in a niche of shadows. I can’t move my feet. Who can know the keel of pain that looms within your form— crushed heart—I’m only twenty five, and not yet a mom. Why am I crying? When Michelangelo released you from the marble, your knees and hands were larger than life. Maybe that’s how you bear this load? With one hand you hold the lifeless body of your son, while your other hand is open to sky, or fate, or whatever it is you trust. If only I were holy like you, Pieta, I could hold my dying certainty. I could maintain the Artist’s plan is good. Not yet. Doctrine is like a chunk of ice drifting in a cold sea, too slight to calve, too dense to melt. Lesley-Anne Evans Lesley-Anne Evans, an Irish-Canadian poet, grieves the death of her mother who passed away in June, 2022. Among her dear friends she counts those experiencing homelessness and/or living in addiction. Through poetry circles, a street level gallery, a storytelling museum exhibit, and times of crisis, Lesley-Anne has learned to be with them. Too many have passed away. Some are thriving in recovery. Lesley-Anne lives in the small woodland Feeny Wood, in Kelowna, B.C., where she offers times of solitude and retreat. A golden eagle was her coffee companion last Friday morning. Lesley-Anne's debut poetry collection Mute Swan is published by The St. Thomas Poetry Series (Toronto). Her work is awarded and anthologized. After The Giantess (The Guardian of the Egg) 1947 She is a Tarot priestess of Lughnasa, her hair a halo of ripened corn in a liminal world where sea and sky merge. She is a Byzantine icon inhabiting an Arcadian Mappa Mundi. She is Queen Elizabeth I who stands astride the globe. But this Faerie Queen treads lightly – she is a nurturing goddess, her ovoid body monumental, capacious her delicate hands cradling the world egg, made whole again after the devastation of a war in which Carrington saw her lover, Max Ernst incarcerated by the Gestapo. He escaped to America but her mind was shattered, and she was committed to an asylum in Spain. Created in egg tempura this is a painting influenced by nursery tales told by her Irish mother and nanny. The wild geese are not the mercenary soldiers of Irish history but harbingers from a world of myth and fairy stories which remained deep within her while she rejected her English upper middle-class background, Carrington found sanctuary and inspiration in Mexico finding kindred spirits in fellow refugees from the European Surrealist circle, including Remedios Varo and other women artists, who were reclaiming, creating and celebrating women as a source of power in painting and sculpture. Edward James, art collector and Carrington's friend and patron wrote: The paintings of Leonora Carrington are not merely painted. They are brewed. They sometimes seem to have materialised in a cauldron at the stroke of midnight. Sue Mackrell Sue Mackrell is a poet, grandmother and gardener living in Leicestershire, U.K., and is of London-Welsh ancestry, Her poems and short stories have been published in literary magazines, anthologies and on the web, including in Agenda, and most recently Whirlagust III (Yaffle Press.) She has an MA in Creative Writing from Loughborough University and retirement from teaching there has given her more time to research and write about women whose stories have been lost, ignored, or concealed. Red Like Fire She sets two large, dark eyes on the room flooded by the red fluorescent light. She has lived shell-shocked in the nearly bare apartment. Little money is at hand to support her small family and herself, newcomers to the city. They live on the least food. Her mind runs in circles when she thinks about it. In bed, her little ones press to her sides. She wants them to feel everything will be okay. The children rely on me, she considers and strokes their small faces. Beyond her, she gazes into the oblong mirror on the wall above the dresser. The eye-like glass distorts her shape on the bed. She sees there her bare arm, the blue blanket that wraps her front. She considers the bends and folds of the blanket in the mirror alongside the idea of her life. What folds and bends am I supposed to unravel?, she thinks. Will my fate become clear if I do? The light from outside fills the room an insistent red, and her heart pulses with the colour. The red seems a fever she is suffering. But it also feels like a great buoy lifting her. Norbert Kovacs Norbert Kovacs lives and writes in Hartford, Connecticut. He loves visiting art museums, especially the Met in New York. He has published stories recently in Blink-Ink, Zephyr Review, MacQueen's Quinterly, and The Write Launch. His website: www.norbertkovacs.net. Bison Paddock Manfred stuffed his blue hard shell suitcase with his underwear and toothbrush, and drove off in his car without knowing where he was going, because Marcie had said, in an impulsive rage while they were fighting, “I regret marrying you.” When he started packing, she fell to her knees and apologized. She wrapped her arms around him as he zipped up the suitcase. But he pushed her off, and said, “I just can’t be around you right now.” It was night in San Francisco, and Manfred drove around the Haight, past neon Victorian storefronts still lit up with mannequins in feather boas and fishnet stockings behind iron security bars. Recently, he had an early stage carcinoma removed from his scalp, above his receding hairline (“You need to sunscreen your chrome dome every day, or it’ll come back,” his dermatologist insisted). He had been obsessed with death, terrified of it. But tonight, since his wife didn’t love him anymore, he felt liberated from the fear. Like, what’s the point of living if your wife doesn’t love you? He checked into The Hotel Majestic, which was anything but majestic. There were clusters of black dots on the wall that could be either mold or bedbugs, and the room reeked of old cigarette smoke. It made him sick. So he went out walking. The Red Vic movie house a few blocks down was playing a midnight movie. He’d never heard of the movie but bought a ticket anyway. Inside, his sneakers stuck to the floor, and the red upholstery of his seat was ripped open so that the beige stuffing showed. He leaned back anyway and watched. It was Perfect Blue, an ultraviolent surrealistic Japanese anime. There was a scene where a woman dressed as a pizza delivery boy gouges out a man’s eyeball with a screwdriver. It was the most revolting thing he’d ever seen in a cartoon. He couldn’t sleep after the movie, so he kept walking until the city streets turned into the grassy rolling plains of Golden Gate Park. He came upon the bison paddock. He wrapped his fingers around the chain linked fence surrounding them, saw the black mounds of fur dotting the meadow. They looked like large muscular dogs, sleeping with their hind legs tucked under their bodies. He’d read that during the 1960s, homeless hippies living in the park would occasionally hop the fence and murder a bison, drag its body back to their tents, and roast the meat and feed everybody in the encampment. He felt sorry for the bison. They’re blind at night, and probably couldn’t defend themselves. He pictured skinny long golden haired men in paisley headbands and bell bottoms slashing at the bison with screwdrivers. Manfred felt an overwhelming urge to be with the bison. So he poked the tips of his sneakers into the holes of the chain linked fence and lifted himself over the top. When his feet hit the ground, he felt a sting in both his creaky knees that he didn’t remember feeling before. A bison nearby lifted its horned head, blinked in his general direction, then rested its muzzle between its paws. Manfred no longer feared death, but he also didn’t want to be on the front page of the San Francisco Chronicle for having been gored by a bison in Golden Gate Park, so he chose a spot in the meadow suitably distant from the bison. He lay on his back, and stared upward. Light pollution drowned out the stars so that they were only a subliminal flicker. It made him long for Yosemite. Decades ago, he and Marcie had lain on their backs in Cook’s Meadow, with the craggy majesty of Half Dome silhouetted by a gazillion stars more luminescent than they had ever seen before, the Milky Way a dripping open gash in the sky. It can get so cold at night in San Francisco. Manfred’s East Coast friends always laughed at him when he told them this, but it was true. Wearing only a black cotton pullover, he started shivering uncontrollably in the grass. His mind clouded over and he couldn’t figure out where he was anymore. Maybe it was early hypothermia. He wanted to be home, but this wasn’t home. Where was Marcie? It was so, so cold, and he couldn’t feel his limbs anymore. He needed to get warm. One of the bison nearby lay on its side, a curly mop top of brown hair between its horns, its snout nuzzled next to a patch of dandelions. Manfred snuggled up behind it, rested his head on its warm hump. He buried his nose into a frizzy patch of fur, the smell of soft wild bodies in wide open spaces. He wondered if this was still Yosemite. Marcie under the stars, rolling up on top of him, unzipping his pants. Eliot Li Eliot Li lives in California. His recent work appears in Ghost Parachute, Cheap Pop, Emerge, South Florida Poetry Review, SmokeLong Quarterly, CRAFT, and elsewhere. No Freedom For the Poor Your shadow pools beneath you, dignity dissolving as you dance for men whose respectable womenfolk watch from a distance no doubt grateful for the fate of birth. You leap as if to hurtle closer to the freedom shining fresh and green as peacocks plumage beyond wide clear windows, men in morning coats standing like rusty barricades intent on stopping your escape and later, as you lie exhausted, does your lover count the francs you earn? does he leave you just enough to buy new petticoats and pointy high-heeled boots, the soles eventually disintegrating as will you from years of forced frivolity. Today your hair is burnished bronze; tomorrow's lack of hope will dim its glow to grey. Linda McQuarrie-Bowerman Linda lives in Lake Tabourie, NSW, Australia by the sea. In this beautiful environment, she writes poetry and has recently dabbled in flash fiction. Linda is completing her degree in Creative Writing at Curtin University and enjoys seeing her work published in various literary spaces. She is a recent Pushcart Nominee thanks to the The Ekphrastic Review. Modigliani ao Carlos e à Cláudia Menezes Na noite em que o gato chegou ninguém descansou lá em casa. O felino passeou-se (da cozinha para a alma) atrás de um papel redondo onde morria para mim mais um poema falhado. O pequeno dândi esguio (de pêlo longo listado) arriscou de colo em colo como que querendo lamber as feridas da casa. O seu gene mais bravio dos bosques da Noruega levava-o a ir cheirar a possibilidade de perigo pela frincha da janela. Passámos a encerrar o acaso com mais zelo. Não toleraríamos mais mortes. João Luís Barreto Guimarães ** Modigliani to Carlos and Cláudia Menezes On the night the cat arrived nobody in our house slept. The feline wandered (from the kitchen to the soul) behind a crumpled paper inside of which one more faulty poem had died. The slender little dandy (its fur long tabby) hazarded a gander at every lap like it wanted to lick the wounds of the house. Its most rambunctious gene inherited from the Norwegian woods led him to go smell the possibility of danger through a crack in the window. That moment we started hedging our bets with more spirit. We wouldn't tolerate any more deaths. João Luís Barreto Guimarães, translated from the Portuguese by Calvin Olsen João Luís Barreto Guimarães was born in Porto, Portugal (June, 3rd, 1967) where he graduated in Medicine. He is a Poet (as well as a Reconstructive Surgeon). As a writer, he is the author of 11 poetry books since 1989, including his first 7 books in “Collected Poetry” (“Poesia Reunida”, Quetzal, Lisbon, 2011) and the subsequent “You Are Here” (“Você está Aqui”, 2013), published in Italy, “Mediterranean” (“Mediterrâneo”, 2016) – National Award of Poetry António Ramos Rosa 2017, published in Spain, France, Italy where it was Finalist of the International Camaiori Prize 2018, Poland, Egypt, Greece, Serbia and forthcoming in the USA, Finland and Czech Republic; “Nomad” (“Nómada”, 2018) – Best Poetry Book Bertrand 2018 and Armando Silva Carvalho Poetry Award 2020, published in Italy where it was Finalist of the International Camaiori Prize 2019, Spain and Czech Republic, forthcoming in Serbia and Egypt; the anthology “Time Advances by Syllables” (“O Tempo Avança por Sílabas”, 2019), published in Croatia, Macedonia and Brazil, forthcoming in India; “Movement” (“Movimento”, 2020), Grand Prix of Literature dst 2022, also published in Macedonia, forthcoming in South Korea. The English translation of “Mediterranean”, by Calvin Olsen, won the Willow Run Poetry Award 2020. His work is published in numerous international anthologies. He has read at literary festivals in Malaga and Pontevedra in Spain, Aguascalientes in México, and Zagreb/Split in Croatia, Bremen in Germany and Washington and New York in USA. English translations have appeared widely. Calvin Olsen is an American poet and translator based in Edinburgh, Scotland. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Boston University, where he studied under Robert Pinsky, David Ferry, and Nobel laureate Louise Glück, and an MA in English & Comparative Literature from The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; and he is currently a doctoral candidate in Communication, Rhetoric, & Digital Media at NC State University. Calvin’s poetry and translations have appeared in The Adroit Journal, AGNI, Asymptote, The London Magazine, The National Poetry Review, and World Literature Today, among many others, and he is the recipient of a Robert Pinsky Global Fellowship and a 2021. Travel Fellowship from The American Literary Translators Association. More of his work can be found at calvin-olsen.com. Twins In Proof, a sword by his side. In its twin, a red ray, ostensibly the red carpet, flows from his hand. In both paintings he’s a pressure cooker. He looks on at his wife—the center of attention-- in her childhood home overlooking Chattanooga. She’s having such fun in her bikini costume, the better to shake up family night. Her sister, on the left, disapproves, jealous that she’s so free with her body: Practically naked in the living room, so inappropriate. The sister can’t wait for them to go back to Bermuda. Tarmac celebrates his return home. Alone. Wherever he goes, in his mind there’s confetti. His children dance and twirl, happy to see him. It isn’t clear if he sees them. Grandmother shelters the baby away, in every family there’s at least one protector. The divorce is pending, as is the pain that requires a separate plane for the load. Lee Stockdale Lee Stockdale’s book of poems, Gorilla, was recently published by Main Street Rag Publishing Company. He and his wife, a potter, live in the Western North Carolina mountains. leestockdale.com Margaret Curtis, a current Joan Mitchell Foundation Fellow, is the artist for Proof: 1964 and The Tarmac, both oil on board, 42” by 84”. margaretcurtisart.com |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|