|

0 Comments

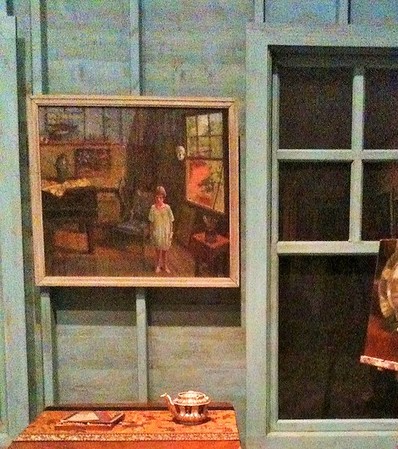

Portrait of a Little Girl, Painted by Elizabeth Chant On display at The Cameron Art Museum The living mask hangs above her— scans the room with white eyes. It watches the girl like they watched you through tiny windows in your room at Rochester Hospital. While you paint this girls portrait she fidgets and sighs as if the three hours she has spent still in her pose is anything compared to the three years you slammed your mind against those breathing blue walls. As you glance over your canvas and give color to the window beside her, Patricia cranes her neck to peer outside into the waning afternoon light. But you paint her face in a straight and forward gaze, tighten the line of her jaw, sharpen her bangs at into the corner of her forehead— her fine obedient hair. What does this girl really know about feeling stuck? About staring out windows in an impotent slump? When you’re a prisoner, windows only taunt you. The scene you see is just flat on the pane— the world outside is a magnet drawing on you, holding your body tight against the cold glass. Pull at her from beneath the wooden planks of the floor in the wine house. Pull with long straight strokes of blue paint through her dress. Stamp down her socks and shoes. Lock her little knees in place. Pin her rail arms to her boney shoulders, a disgruntled paper doll. She’s really grown impatient now. But what does this girl know about being stuck? Tell her, Elizabeth. Tell her it’s easy. Say go ahead child, there’s a jar of brushes on the table right beside you. All you have to do is pick one up and paint yourself a way out. Veronica Lupinacci Veronica Lupinacci grew up in Sarasota, Florida. She received her MFA in Creative Writing from the University of North Carolina Wilmington. She has taught writing at the university, high school, middle school, and elementary level. Her poems have recently appeared in The McNeese Review, Haiku Journal, The Pinch, Northwind, and Eunoia Review. The Art Project by Sherod Santos Poet, essayist and translator, Sherod Santos is the author of six books of poetry, a book of translations, Greek Lyric Poetry: A New Translation, and a book of essays, A Poetry of Two Minds. Mr. Santos has received an Award for Literary Excellence from the American Academy of Arts and Letters, as well as grants from Guggenheim Foundation and the National Endowment for the Arts. He lives in Chicago.

Untitled #751

Maybe winter, maybe nothing; negative space become positive, like a memory of snow. Something was lying there behind her eyes, where she could only feel it. And still, it drifted in the clouded mirror above the bed, in the steam from the teakettle and the picture frame that enclosed an iteration of her brother, seven months dead. Words fell from the ceiling. She wrote for an hour. (He would have known what needed to be said.) Quiet, so quiet, they lay on the page remote and unspoken. Rebekah Curry Rebekah Curry is an alumna of the University of Kansas and the University of Texas at Austin. Her chapbook Unreal Republics is available from Finishing Line Press, and her work has also appeared in journals including Antiphon, Mezzo Cammin, and Blue Lyra Review. See more at rebekahcurry.tumblr.com. Coefficients

so much of how i think d e p e n d s on stringing your imperfections into neutered emotions, and surgically placing them alongside my pseudo-hankering for this (us) to (not) go awry. Shloka Shankar Shloka Shankar is a freelance writer from Bangalore, India. She loves experimenting with Japanese short-forms of poetry such as haiku, senryu, haibun, and found/remixed poetry alike. Her work has recently appeared in Failed Haiku, Otoliths, Poetry WTF?!, Window Cat Press, Random Sample Review, and so on. She is also the founding editor of the literary & arts journal, Sonic Boom. On Allen Ginsberg by John Loengard

The bridge of his nose holds out Against the fire, But the nostrils can't be saved. At least he can't smell His skin burning, can't taste His dissolution With a tongue of ash. Smoke slips in a noose Over wire-coil hair And tightens. One hand-- Thumb claimed by flame-- Clutches at vapor, Comes away empty. Four fingers (soon to be three Then two one none) Grapple with the rope. It only moves as smoke moves, That bright ghostly dance Unmoved by him. He could turn his black-rimmed glasses, His one squinted eye with its pale lashes, To look out the window But it's the light that burns him. From a crack in thick-folded drapes, Rays radiate onto his temple Like nuclear fallout, atoms split And unstable that take out their fury On the broken world, break it more. Throat, lips, nose, all smoke. How could he breathe? His body transforms Its state of matter, becomes the air Becomes the rush of burning Becomes as free and insubstantial As the smoke that swallows him. Sarah Abbott Sarah Abbott is an MFA candidate and teaching assistant at the University of Kentucky. Her work has previously appeared in Polaris, Fly in the Head, and the anthology Feel It With Your Eyes. She loves traveling as much as coming home. My Life with Matisse

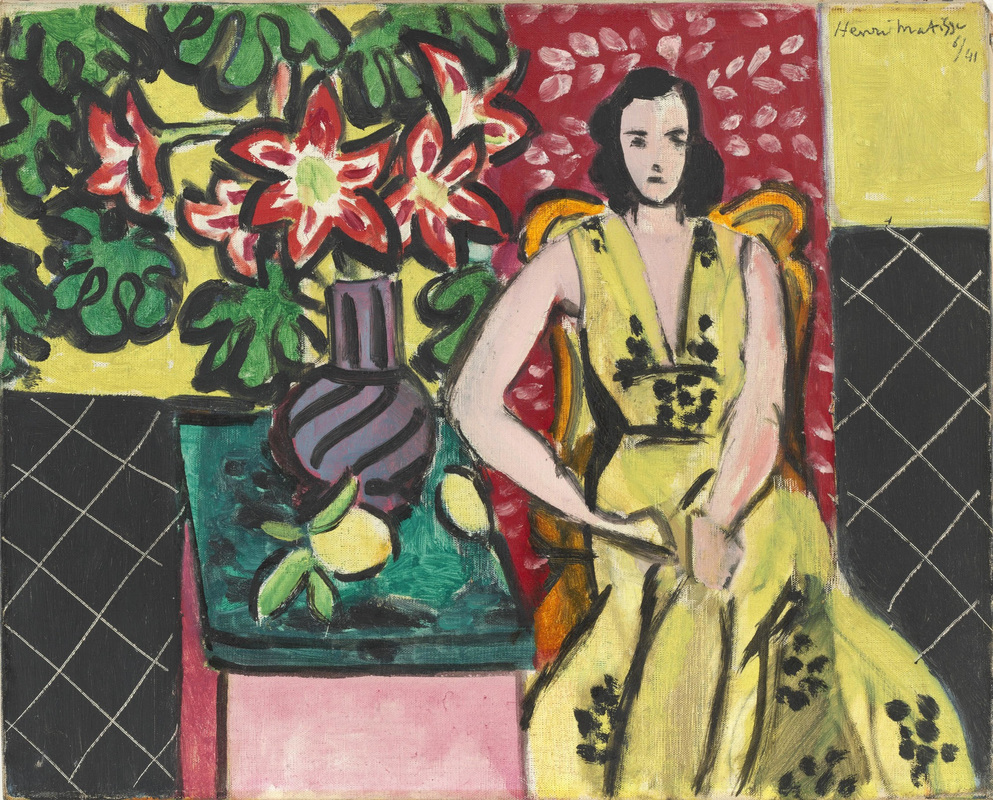

I drink Matisse first thing in the morning I breathe Matisse all day long I eat Matisse in the evening I dream Matisse midnight to dawn. I require the red of beets, blood, and tomatoes The green of emeralds, limes, and pines Lemon yellow, fuchsia, and orange Every blue, from deep ocean to pale sky. I crave anemone and amaryllis and goldfish I must have bathers and dancers and nudes Patterned upholstery, carpets, and wallpaper Lush flowers blooming inside and out. When I gaze at Matisse, he frees me Even in faded art books or on a computer screen Matisse feeds me, he heals me, he leads me He teaches me to invent what I need. Sheila Wellehan Sheila Wellehan is a poet who lives in Cape Elizabeth, Maine. Her work has appeared or will appear soon in Chiron Review, Poetry East, Rat's Ass Review, and Yellow Chair Review. Like Minded

Beware the one who raises a headless army, shapes sinew and bone from mud like some golem brigade. Danger, armed only with obedient parts, feet all pointing in the same direction. They wait for The One with Lips to yell, “Forward!” Without the yellow warning light of conscience, they process only black and white, on or off. Motionless, they pose little threat. But crowd mentality quickly kindles in the thrill of crashing glass and cheering stadiums. Risk escalates when the ranks explode with others longing too much to belong. Alarie Tennille Alarie Tennille was born and raised in Portsmouth, Virginia, and graduated from the University of Virginia in the first class admitting women. She became fascinated by fine art at an early age, even though she had to go to the World Book Encyclopedia to find it. Today she visits museums everywhere she travels and spends time at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, where her husband is a volunteer guide. Alarie’s poetry book, Running Counterclockwise, contains many ekphrastic poems. Please visit her at alariepoet.com. Umbrellas

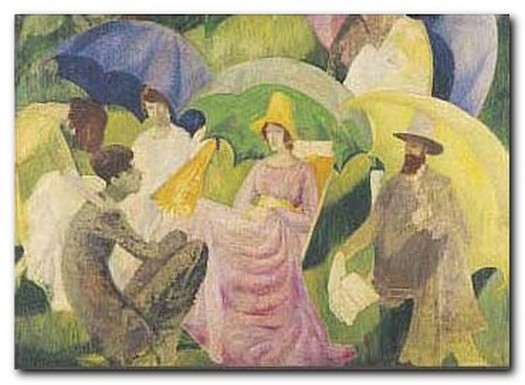

On the day I visit the gallery, it is raining. Manchester, famous for rain, revolution, and football, lives up to its reputation, and Mosely Street in March—seen from the third storey—glistens with passers-by holding dark umbrellas aloft. Brett, Dorothy (1883-1977), hanging here on the white wall of the gallery, painted umbrellas in bright colours, parasols, really, for the sun. She does not call them parasols. Her bleak pessimism announces that it will surely rain soon. Curved backs recline. Lytton Strachey, knees crossed under a yellow umbrella, book falling limply from his hand. Ottoline Morrell, on whom Dorothy has a crush, resplendent in pink silk, folding her hands in her lap beneath a sheath of green. Behind her, perhaps, Virginia, who was not yet Woolf, and Leonard, curled into blue and pink umbrellas, oblivious to the party, the absence of Vita not yet felt. No sign of Lawrence here. The slight man paying court to Ottoline is too tall, too dark, too earnest to be Lawrence. Lawrence came later, cast Ottoline into controversy, drew Dorothy into his orbit. She followed him to Rananim—Dorothy, that is—by boat, leaving behind the grey March drizzle. In the heat of a parched New Mexico she put down roots, seeing no need now to paint umbrellas. On the day I visit the gallery, I do not have an umbrella. I take shelter under Dorothy’s, spending long moments soaking in the warm light. Later, in the gallery gift shop, I buy a postcard of her umbrellas, slip it between the pages of a book I am reading, forget it is there. I’ll find it later still, when I have travelled above the clouds to leave behind the grey March drizzle, when I, too, have put down roots in American soil. Unlike Dorothy, I still need an umbrella. I keep hers in a small frame on my sunny kitchen wall, in case it rains. Catherine A. Brereton Catherine A. Brereton is from England, but moved to America in 2008, where she is now an MFA candidate at the University of Kentucky. Her essay, "Trance," published by SLICE magazine, was selected by Ariel Levy and Robert Atwan as a Notable Essay in Best American Essays, 2015. She is the 2015 winner of theFlounce’s Nonfiction Writer of the Year award. Her more recent work can be found in Crack the Spine, The Rain, Party, and Disaster Society, The Watershed Review, The Indianola Review, Literary Orphans, and The Spectacle, and is forthcoming in GTK Creative Journal, and Burning Down the House anthology. Catherine is the current Editor-in-Chief of Limestone, the University of Kentucky's literary journal. She lives in Lexington with her wife and their teenage daughters, and can be found online at catherinebrereton.com. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|