|

The Reveal Our conversation splays just short of the end of wanting. When she cracks an oyster, you know she’ll amaze you with a pearl but no, she passes you a sapphire, then an opal. Once you warm these stones in your palms, she holds out a pearl, any pearl, now that your eyes are ready. It’s the first pearl your eyes have ever seen. Your words don’t fit your mouth anymore. You thought you had a hand but it’s an oyster shell. How will you ever hold her? Unbutton her? Richard Ryal A poet, professor, and editor, Richard Ryal has worked in marketing and higher education. He stops for no obvious reason sometimes and no one can talk him out of that. His recent publications include Notre Dame Review, Sheila-Na-Gig, and The South Florida Poetry Journal.

0 Comments

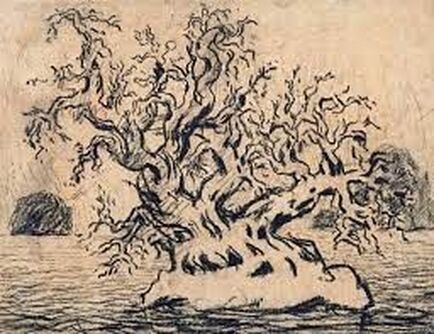

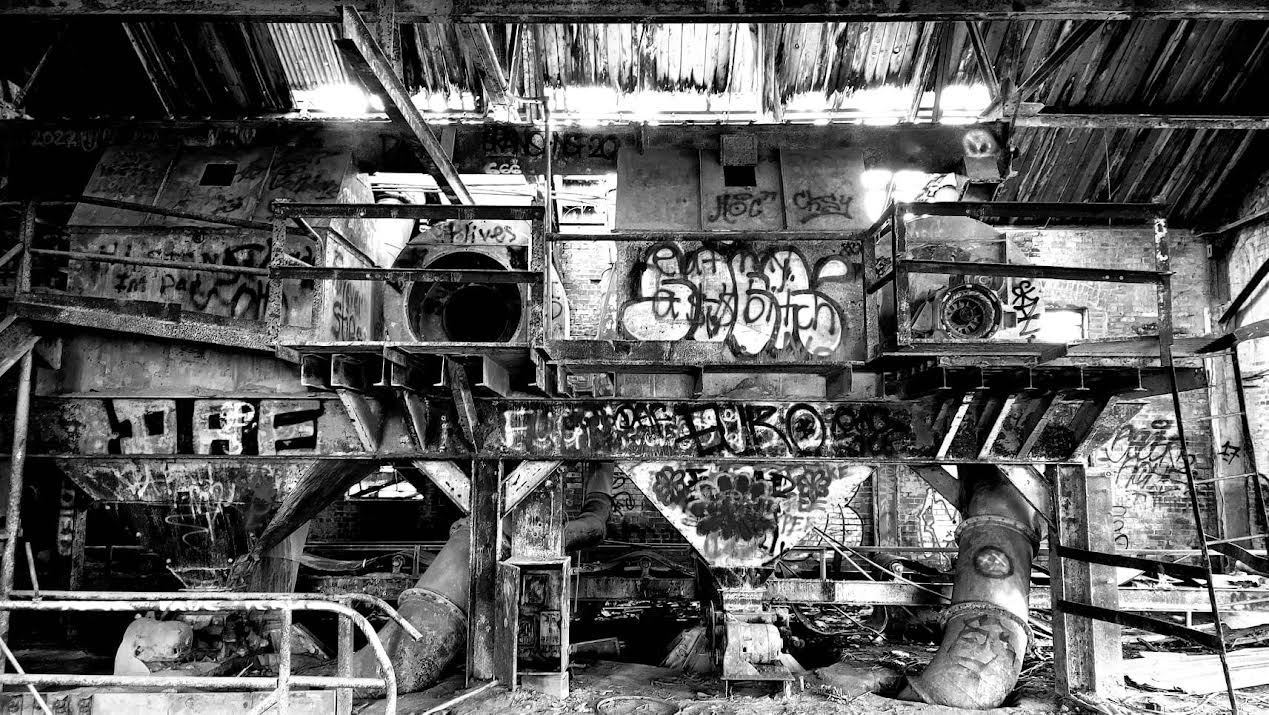

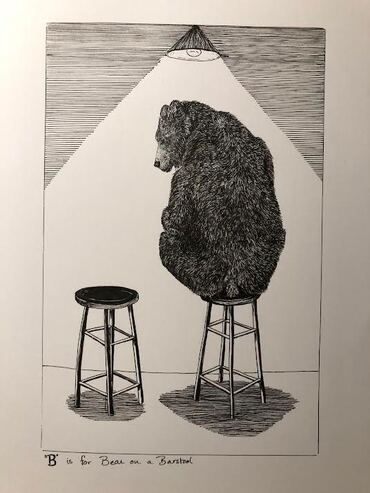

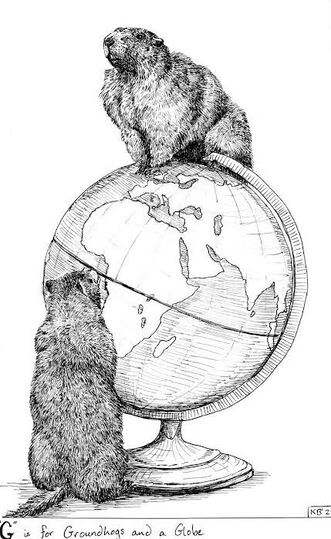

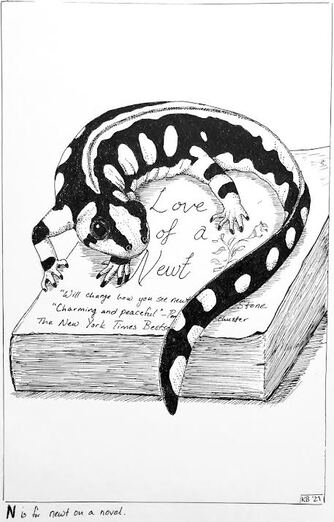

The Roadside Adoration of Gauchito Gil I pedal up the path and see it—the tree fluttered in red, its branches banded in wishes, tied higher than the small, see-thru box mounted at head height on the trunk. When the wind gusts, it must carry prayers as it carries stories, wave them in a frantic dance like the flap of flags that the little boxed gaucho, mustached, tucked inside, must understand. His hand clutches las bolas, arm about to spring, swing, and release, entangle any runaways; though his own sought body is stilled, captured, finally, by the shrine. By likeness but not in effigy. Elevated this time by the tree that holds him. Strung with red venerating beads. Festooned with plastic flowers. It's the fifth altar I've laid eyes on today. The others I'd scanned from my brother-in-law's car in the drive between Cruz del Eje and San Marcos Sierras, where my husband's mother lives. They were easy to spot: clumps of red ribbons, trees tangled with gratitude for favours granted. When I'd pointed to one of the shrines, my brother-in-law had said: We are a people whose passion has nowhere else to go. Then he'd claimed that even Messi thanked Gauchito for his World Cup win. What makes sense to me as I look at this replicating altar, this channeled passion, this community-erected art, is the desire for something to hold in the hand. Not to keep, but to throw. A flung hope, like a human life, or the soul's leap into outlawry. Rejection itself a kind of makeshift faith, a push forward without plan or replacement. Perhaps the replacement is just living—making it up as one ambles on. Maybe passion must wander, not unlike the sainted fugitive folk hero behind the figurine. Who else could be bold enough to grant wishes, I think as I stand before the miniature homage, my bicycle laid at the roots of this rough road. Angela Sucich Read an ekphrastic story by Angela Sucich, The Things We Grow. Angela Sucich holds a Ph.D. in Medieval Literature from the University of Washington. Her poems and short prose have recently appeared in such journals as Nimrod International Journal, Cave Wall, and Whale Road Review, and in 2021, she was honourably mentioned for the Pablo Neruda Prize for Poetry. In 2022, her chapbook, Illuminated Creatures, won the New Women's Voices Chapbook Competition and will be published in 2023 by Finishing Line Press. Picture of a House There are several V’s in my daughter’s drawing. One is a gable and the rest are birds flying off into the spiky yellow sunset she’s coloring in on the kitchen table. From where I sit opposite her, writing a check to the Hartford Federal Mortgage Corporation, the birds are houses, and the house is a large bird, a vertical triangle from eaves to ridge, ready to take off at the drop of a letter, rooftop flapping over the treetops to Hartford, Connecticut… I sign the check as she signs her picture in the bottom right-hand corner, and the birds migrate softy into my hands as she gives me the house. For keeps. No strings attached to the birds which could also be houses, or the sun which could also be time running out, going down like a diminishing crayon stub still eking out, incredibly, enough yellow to warm a house thirty years. Paul Hostovsky Paul Hostovsky makes his living in Boston as a sign language interpreter. His latest book of poems is Mostly (FutureCycle Press, 2021). He has won a Pushcart Prize, two Best of the Net Awards, and has been featured on Poetry Daily, Verse Daily, and The Writer's Almanac. paulhostovsky.com Swedish: Hill’s Tree Hill’s tree grasps for the heavens as with a claw. The sun is surrounded by one black-shimmering, trembling, dancing. When one sees the sun, one sees black. An impenetrable cluster-darkness manifests. The tree’s body has eyes. It is a book-tree. The trunk has become knots of concentrated time, bound in tough clumps, deeply eroded furrows, creases, fine wrinkles force themselves forward through the silky-smooth thin bark-skin. The clumps of time are compressed impoverished faces, they have eyes. Farthest inside the darkness the tree sees: the innermost of life is salvation; the outermost is death; this is the heart’s beat. In the tree vaults, shadows of light, mighty flickering animal-shadows, the death-animal’s heart. Birgitta Trotzig, translated by Bradley Harmon Hill’s Waterfall Hill’s waterfall is neither high nor low. It is beyond – like when I one year at Eastertime (the light across the sea) found the overflowing brook’s outlet in the Baltic, transparent water roared and streamed down staircase waterfalls over the slate rocks out into the sea, I then remembered a dream: a waterfall (“ninety meters,” people said, but it looked immensely higher), a silver thread against the dark back of a mountain, the precipices plummeted straight down into a dark blue lake which dimly reflected the blinding white looming iceberg above the thousand-meter black ridge, all without proportion, however big, however small. – How the iceberg seemed slowly to come to life, to swell, to glide, to move. – It turns out that not a man is left in that neighborhood any longer, all the houses are emptied and abandoned. We stand on an echoing empty city street and stare out alone, abandoned ochre houses trapped deeper and deeper under the power of a progressively darkening blue-green shadow, colder and colder, later and later in the day – the iceberg is on its way, we are alone in the emptiness and the silence of the vast natural world. How the huge folding ridge of ice, the translucent darkening icebeast will roll over the ridge into the lake. The floodway of rising water shall bury us. The menacing green-blue mountain range on the horizon. Now the waterfall is giant, translucent, a primeval beast’s death glare, a world ceasing - the silence before all, after all. Birgitta Trotzig, translated by Bradley Harmon These poems are Birgitta Trotzig's prose poem collection, Anima, 1982. Birgitta Trotzig (1929–2011) is one of the twentieth century’s most revered Scandinavian authors. She wrote across many genres and is particularly acclaimed for the 1982 prose-poem collection Anima, the 1972 novel The Malady, and her 1985 masterpiece The Marsh King’s Daughter. She was elected to the Swedish Academy in 1993 and awarded many of the major literary prizes in Sweden. Her work has been translated into over a dozen languages. Bradley Harmon (b. 1994) is a writer, translator, and scholar of Scandinavian and German literature, philosophy, and film. His translations have appeared in many literary journals and his book translations include Birgitta Trotzig’s The Marsh King’s Daughter, Katarina Frostenson’s The Space of Time, and Monika Fagerholm’s Who Killed Bambi? He was invited to the 2021 Översättargruvan translation workshop in Sweden, placed second in the 2022 Anne Frydman Translation Prize, and is a 2022 ALTA Emerging Translator Fellow. He lives in Baltimore, where he's completing a PhD at Johns Hopkins University. Dear Readers and Writers,

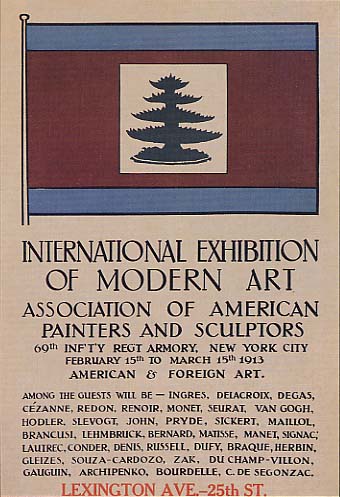

As founder and editor of The Ekphrastic Review, I admit it has been my dream since early days to have print anthologies of our authors' brilliant ekphrastic works out in the world. I am over the moon to announce this call for submissions to The Memory Palace: Ekphrastic Flash Fiction and Prose Poetry. This will be our first print anthology! I am even more thrilled to announce a very special guest as co-editor. I am excited to collaborate with Clare MacQueen, curator and publisher of MacQueen's Quinterly, an incredible journal. Clare is so generous and supportive of writers. And she shares my passion for ekphrasis, a big part of her journal's offerings. Clare's pages have been outstanding resources for and archives of flash fiction and microfiction- her previous journal was Knock Your Socks Off Flash. And like myself, she has a special place in her art and pages for prose poetry. Many of our readers and writers here at The Ekphrastic Review already know and love MacQueen's Quinterly. Clare and I have talked for some time about teaming up and we are so happy that this project is now under way! (Scroll to end for Clare's bio.) Why flash fiction and prose poetry? There are countless novels inspired by visual art and at least as many collections of ekphrastic poetry. (We love novels and poetry!) There are some ekphrastic short story collections, but a paucity of ekphrastic prose poetry books or books of ekphrastic flash and microfiction. There are amazing art-inspired flashes and prose poems out there, as readers of this journal are well aware. We'd like to show them off on more bookshelves! We challenge all of you poets to try your hand at some prose poems for this project! The theme of this anthology is MEMORY. "Inside everyone, there are secret rooms," wrote Charles Simic in Dime Store Alchemy, his famous collection of ekphrastic prose poems after Joseph Cornell. We want stories and prose poems that brave those secret rooms. For this anthology, there are no specific art prompts. TER's modus operandi has been to provide an array of art prompts on a theme. This time, you can choose paintings or other visual works of art that trigger, reveal, or suggest a memory in some way. How you interpret the theme and imagery is entirely up to you. Rules 1. The theme is "memory." How you interpret this theme is up to you. 2. Flash fiction and prose poetry up to 1000 words. 3. Submit up to three stories or prose poems. Combining flash and prose poetry submissions is fine. 4. You will respond to artwork of your own choosing for each piece. This can be any painting, sculpture, fine art photograph, collage, etc. Your work will be inspired by the art you choose, as well as the theme. You can write from the artwork in any direction you are moved to. Follow your inspiration. Artwork will most likely be referenced but not reproduced in the anthology, due to cost and copyright considerations. 5. Send your works together in a single Word document. Include a brief 100 word bio in the body of your email, not in the document with your stories or prose poems. 6. Do not include your name in the document. Works will be read blind. 7. Submit works with subject line MEMORY to [email protected]. 8. Include the title, artist, country and date for each artist, along with a link to view the art. Example: Memory Lane, by Jane Doe (Mexico) 1996. www.link.com 9. There is no entry fee. 10. Contributors selected for the anthology will receive a PDF copy. The print anthology will be priced as low as possible to make it widely accessible to everyone, with the PDF version available free to anyone. 11. The anthology will be published by The Ekphrastic Review. 12. The selection of the editors will be final. 13. Stories and poems must be unpublished. Simultaneous submissions are fine, as long as you alert us immediately if your work is selected elsewhere. 14. The deadline is September 1, 2023. 15. Please tell everyone you know who would be interested about this opportunity. ** Clare MacQueen is founding editor and publisher of the literary journals MacQueen’s Quinterly and KYSO Flash. She edited, designed, and published 20 print books via KYSO Flash Press (retired 2020). Her own fiction, nonfiction, and poetry appear in Bricolage, Firstdraft, New Flash Fiction Review, and elsewhere; and her essays, in Best New Writing 2007 and Winter Tales II: Women on the Art of Aging. As webmaster for Serving House Journal, MacQueen published 18 issues from 2010 to 2018. She also co-edited Steve Kowit: This Unspeakably Marvelous Life (Serving House Books, 2015), and served as a judge for the 2017 Steve Kowit Poetry Prize and for the 2021 Jack Grapes Poetry Prize. Judgment Day through cement earth whatever lies beneath up thrust arms hungry unloved looking for an embrace ravaging refuse of paradise they seek to drag down souls angels gods play dead they will know someone is here they feel thought moving breath breathing hearts beating bracelets of macho tattoos in unknown languages black-hearted Samson arms pull down temple pillars our handiwork scrawled across rusted lintels of Eden sweat of the brow rust thorn and thistle brush dust has come to claim us Smile You Are Slack-jawed, sans flesh, sans all sense of who we were, we recycle from the chrysalis of questions, of waiting to become, head in the clouds, the last bulb of clarity yet to click on. Drawn to what looks like stuck-on-a-pole redemption, in some other neighbourhood, dimension, in the adulthood where we seem to recall we used to live, Godzillas of the afterlife, we lurch on, screeching like bad brakes towards the Promised Land Buffet, loading up our piggy-back platters with Smith Transport, which transports us nowhere, fills nothing in the hold beneath our ribs, and we remain parked and hungry in front of what may have been our lives, no longer rolling stock, with only the promise of ice cream and Edelweiss. Echoes cackle, a subtraction of voices in the hollow high meadows of our skulls where memories are bone white and brief, like lives maybe, like all the maybe lives we will ever live, have lived, will never live, like the one stubborn light which never enlightens. Foot-bones stub against the inflatable pool of childhood with all its warnings, all its ignored hazards. We settle in to shallowness, the place we once were happy, splash ourselves with the not yet learned and, like the sign says, stay squirelly. Full Immersion I seek the full immersion experience, thumb and forefinger of holiness clamping my nostrils, rainbowing me over, other hand bracing the small of my back. Around my hips the postulant’s robe floats, a white lily upon the face of the waters, the preacher’s salving words gurgling in and out of my ear canals with the ebb and flow of blue-green water, ceramic-tiled tub standing in for the River Jordan. My sins wash away with stains gone before, swirl down the drain hole of redemption when the Lord’s janitor pulls the plug. I am pumped for sainthood, pumped to be, at last, among the chosen, to get my ass up off the sidelines, out of the bleachers, rah-rah-sis-boom-bah the angelic band down the court of Beulah-land to victory, the celestial spree of slam dunks, buzzer-beaters, carried aloft on winged shoulders of apostolic teammates. I’m weary of rummaging mortal garbage pails for heaven’s leavings, holding cardboard signs with sketchy pleas, kneading canned heat into iced hands under crumbling bridges from nowhere to nowhere. I’m tired of the everyday, the 9-5, the humdrum, the absence of wings ascending. The void of cars in the lot, broken windows, lack of any wheeze from the A/C, does not deter me. Christmas lights, after all, are up. I am ready. Sweet Jesus, I am ready. Stop I drop into neutral and race the engine and think of you and that flag you threw and how I said What Where When while you counted off the yardage and I threw a challenge to no avail no points scored which was always a loss for me right down to the wire was always someplace over our heads we never learned or we learned too well and I could go on with the football play-by-play but it was never a game really as I sit here deciding whether to trip ahead wheel right maybe left does it matter I don’t think so till I see that blur-in-the-dark rainbow overarching STOP and I think turn around go back yield the field you didn’t blow the whistle the ball is still in play I was wrong Baby O I was wrong whatever it was though that Hail-Mary pass could just be the streak of my windshield wiper and I can’t seem to get myself up off the gridiron Standard Time Is this how the world ends? One screw loose, and it all falls apart. Every thing we know, everything we love, everything we are, screeches to a halt. Empty streets straight out of the Twilight Zone. Traffic lights stuck on red. What’s the point of a no-right-turn sign if we never make it to the intersection? On the other hand, pun intended, go left, young man. This crossroads has got an angle, but the march of time is at parade rest, and we can’t see it. Wasps, or the spawn of some devil prairie weed, lie feet up beneath the even keel of eternity. Question is, when did we join them? The empty store front sells no answers. The sky threatens, but will never carry through. We, however, have no time on our hands, and we are coming for you, HowardXMiller. Robert L. Dean, Jr. Robert L. Dean, Jr.'s poetry collections are Pulp (Finishing Line Press 2022); The Aerialist Will not be Performing: ekphrastic poems and short fictions to the art of Steven Schroeder (Turning Plow Press, 2020); and At the Lake with Heisenberg (Spartan Press, 2018). A multiple Pushcart and Best of the Net nominee, his work has appeared in many literary journals. Dean is a member of the Kansas Authors Club and The Writers Place. He has been a professional musician, and worked at The Dallas Morning News. He lives in Augusta, Kansas, midway between the Air Capital of the World and the Flint Hills. Jason Baldinger is a poet and photographer from Pittsburgh, PA. He’s penned fifteen books of poetry the newest of which include: A History of Backroads Misplaced: Selected Poems 2010-2020 (Kung Fu Treachery), and This Still Life (Kung Fu Treachery) with James Benger. His first book of photography, Lazarus, as well as two ekphrastic collaborations (with Rebecca Schumejda and Robert Dean) are forthcoming. His work has appeared across a wide variety of online sites and print journals. You can hear him from various books on Bandcamp and on lps by The Gotobeds and Theremonster. His etsy shop can be found under the tag la belle riviere. Untitled Composition Like the word, paint always became something more when she moved it. Her stroke, a spell she did not understand beforehand, spoke. Not until she let herself fall to the centre could she see the story she had made rise up around her. Kathryn Douglas Kathryn Douglas is the director of a university writing program, has been teaching undergraduate writing and graduate writing pedagogy for many years, and has an MFA in creative writing with a focus on poetry from Fairleigh Dickinson University. Her current academic research focuses on using ekphrastic poetry to help freshmen see their creative potential as writers, and most of her writing has been academic, so she's working to find more time for poetry. She loves to read, write, sing, garden, hike, and visit art, and, in particular, photography museums. Bear on a Barstool A grizzly is sitting in a spotlight, looking at something that is missing. He is slumped, a sack of black fur, his long snouted black-nosed face gazing at the empty bar stool to his left. The weight of the universe is on his shoulders, shimming down through his fur black torso to the base of his spine, his tailbone pressed against the wooden seat, high on its four thin cross-linked legs. It is not clear whether this is a bar, this Hopper-like pen and inked scene. It really doesn’t matter – just two bar stools, one bear, a spotlight. It could be a stage, and he is waiting for someone to make an entrance. Whatever, this bear is looking for someone – at someone – who isn’t there, this precarious bear. The white space above the empty stool is the yin to his yang, the anti-matter of black. He could move to that stool like a missing piece of a jigsaw, but that would leave a void where he is right now. There is no practical solution to this problem, unless the artist can help him. Groundhogs and a Globe Gary is sitting on the North Pole, his front paws neatly positioned, side by side, just to the west of Ireland. He is looking majestic, nose in the air. Below him Graham is sitting tall, short-tailed, his snout against the equator. He appears to be scrutinising Côte d’Ivoire. Occasionally he looks up at Gary. Gary is sniffing the air. Graham wants to be up there too but there is no room, and the sides of the globe are high and smooth. Graham makes a salad of dandelion, coltsfoot, buttercups; places the plate on the desk, next to the base of the globe. Gary sniffles, slithers, slips, lands on the desk, gnashes the greens with his ivory teeth; and while he is eating, Graham starts to climb, reaches Egypt, his long claws rasping and sliding. The globe begins to spin, faster and faster, as he scrambles, jumping the arm on each pass, blue and land whirling to white. All Gary hears is a high-pitched whistle – then nothing. Ibis with an Inkwell My dear Itsuhiko, – Unless anything happens to change my plans, I propose to fly to Japan tomorrow. It has been a long time since we met in Uttar Pradesh, all those summers ago. I remember the day that you built me a nest in a saltwater marsh, a solid construction of carefully chosen sticks, lined with silvergrass and silken threads; how we nuzzled together at night. A lot has happened since then. I settled down with an antiquarian, surrounded by relics and rare books, including (you may be interested) Browning’s own copy of Pauline (Saunders and Ottley, 1833). My antiquarian, himself an antique, sadly passed away last winter. I put the collection on eBay, got enough to pay for a pond of my own in its own private wood. Life’s been good but, my dear, I always wondered what would have happened if the monsoon had not come that day, if you and I had not been washed away. My head is black from drinking the ink; I cry black tears when I write. I hope that you can read this; I hope that you are there. Until tomorrow, my dear Itsuhiko Kite and a Kite Bridle and tail, lift and drag; she is tethered by an invisible hand. He is entranced by her abstraction, the familiarity of her form. She has his colours, yet is translucent; the sunlight shines through her wings. He flies below her, shadows her; is solid between her and the Earth. He watches her soar and glide, shifts in her ghostly shadow: the doubles and seconds of real things. Newt on a novel You know, this book is really not that good. It is not about l’amour du triton, affairs of the salamander, the rapture of the fast-flowing stream. It is not about how newts can regenerate arms, legs, even tears of the heart. It is not about exothermic love, or the bed of a river, the deep blue ocean, where newts are at one with each other. It is about a Kaiser Mountain Newt held captive, fed on blackworms, bloodworms, second instar banded crickets; his biography, from hatchling to eft; how he became a preacher of water; how the water vanished into the sky. The pages of the book are soaked, curling. Anne Osbourn Anne Osbourn: "I am a plant scientist based in Norwich. I started writing poetry in 2004 when on sabbatical in the School of Literature and Creative Writing at the University of East Anglia as a National Endowment for Science, Technology and the Arts Dream Time Fellow. My poems have been published in poetry magazines and international science journals. My first poetry book Mock Orange (SPM Publications) was a winner in the 2018 Sentinel Poetry Book Competition. I am also the founder of the Science, Art and Writing Trust (www.sawtrust.org), an educational charity that uses science as a meeting place for interdisciplinary adventures. Kirsten Bomblies: "I am a professor in genetics and evolutionary plant biology based at the Swiss Federal Technical University (ETH) in Zürich Switzerland. I have been drawing my whole life. 1992-1996 I worked part time as an illustrator in palaeobotany and palaeontology to pay the bills while at university; this started my love affair with ink illustration. My fascination for combining human-associated objects with animals began fairly recently – while I lived in Norwich five years ago; the Alliterative Animal Alphabet followed as a two-year project, finished in 2020. Art is where I find respite from an intense daily life, which is why I generally reserve it as a hobby – to protect my love for it. " William Carlos Williams: A Journey Into Art ‘The real innovations in art and in life, whether in literature or painting, depend on the manner in which the elements of one medium are translated to the conditions of another.’ Bram Dijkstra Several years ago, I attended an exhibition of the collected works of Kasimir Malevich in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. What struck me as I moved from room to room was that, in this astonishingly diverse one-man-show, I was witnessing the very development of modern art. It also occurred to me at the time that Malevich’s wide embrace of the emerging styles within modernism had much in common with the ekphrastic poetry of William Carlos Williams (1883-1963), a poet whose close involvement with the visual arts resulted in many successful attempts to break through the boundaries of his own medium (as Dijkstra expresses it). Indeed, as we move, so to speak, from poem to poem, we find the influence of many diverse modernist styles reflected there, and the sheer variety of these texts suggests that Williams was exploring his aesthetic milieu with the same intensity that Malevich explored his. In this essay, I trace Williams’ whole-hearted embrace of the world of art that altered the very nature of his poetry and, as in Malevich’s paintings, reflect the developments in the visual arts themselves. From Keats to Picasso ‘undying accents repeated till the ear and the eye lie down together in the same bed’. (‘Song’, 1962) Written at the end of his life, these lines from ‘Song’ offer a witty self-retrospective on Williams' continual engagement with the visual arts. His choice of a biblical allusion here suggests the unlikely joining of two seemingly incompatible entities: the visual and the verbal arts and the boundaries that divide them. These lines are also the poet’s final signature to an entire body of work in which the visual arts play a central role, much of the poetry illustrating Williams' conviction that ‘to bypass the eye, you bypass the mind’. It’s not surprising that Williams focuses on the sense of sight in his verse, as his first artistic efforts were not in writing but in painting. As he states in his preface to Selected Essays, ‘I almost became a painter, as had my mother been before me, and had it not been that it was easier to transport a manuscript than a wet canvas, the balance might have been tilted the other way.’ Of course, Williams was not the only poet/painter of his generation, nor was he alone in integrating elements belonging to the visual arts into his poetry. Yet his inter-art experiments were far more diverse and had more far-reaching consequences than those of his contemporaries, and the poems which grew from these ventures into the visual arts were to have a profound impact on the development of American poetry. New Beginnings Williams’ understanding of the ‘undying accents’ in his poetry as an equal fusion of the visual and verbal were the product of a long poetic journey, one that reflects the unfolding history of the visual arts in the first half of the 20th century. But his first poems (published in Poems 1909, and The Tempers, 1913), do not carry any suggestion of the impact that the visual arts would soon have on his poetry. These early poems, in fact, were quite different from the sharply-focussed and clean-edged verse for which Williams is best known. His 1909 poem ’First Praise’ is a good example of how little these poems carry Williams’ later conviction that poetic language must have a direct and unadorned relationship with its object: Lady of dusk-wood fastnesses Thou art my Lady I have known the crisp, splintering leaf-tread with thee on before White, slender through green saplings; I have lain by thee on the brown forest floor Beside thee, my Lady. Lady of rivers strewn with stones, Only thou art my Lady Where thousand the freshets are crowded like peasant to a fair Clear-skinned, wild from seclusion, They jostle white-armed down the tent-bordered thoroughfare Praising my Lady. These studiously romantic lines were written as an occasional poem recalling a visit to Williams’ girlfriend Flossie and her family at their summer home in Cooks Falls, New York. Aside from its excessive sentiment in view of the occasion, the poem does not yet suggest Williams’ later drive toward minimalism, which was soon to do away with what he called ‘stock responses, overripe images and the decayed rhythms of the language’. Williams himself looked back on poems like this one with dismay at their ‘falseness’ and the fact that ‘I knew nothing of language except what I’d heard in Keats or the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood’. Yet by the time Williams had written ‘The Arrival’ in 1915, it is clear that he had not only rejected the language of his earlier poems but presented even the objects of his devotion from a perspective unclouded by romantic idealism: And yet one arrives somehow, finds himself loosening the hooks of her dress in a strange bedroom Feels the autumn dropping its silk and linen leaves about her ankles. The tawdry veined body emerges twisted upon itself like a winter wind. The difference between these two poems suggests that a remarkable development had taken place in Williams’ approach to his verse. Indeed, ‘First Praise’, with its focus on idealised beauty, prevents any concrete perception of the lady herself; but in ‘The Arrival’, a more realistic image of beauty emerges - one that lies outside the tradition of the love lyric and other poetic norms. But more than this, we also find here a significant deviation from the conventional idea of poetic subject matter: a ‘tawdry, veined body, is quite unlike the kind of beauty that inspires the praise of a ‘thousand freshets’. Although this later poem is still far removed from the form Williams’ poetry was to take, its engagement with the object (which at this point has as much to do with the ‘Objectivist’ movement as it has with the visual arts) is still far more direct than the distancing panegyric of ‘First Praise’. Williams’ drive toward minimalism eventually produced poems like ‘This is just to say’, a husband’s loving apology to his wife: This is just to say I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold. So what happened in these intervening years that would have had such a pronounced impact on the structure and focus of Williams’ verse? The Armory Show of 1913 happened. The Armory Show Officially known as the ‘Exhibition of Modern Art at the 69th Regiment Armory on East 25th Street’, the show was launched by the avant-garde Association of American Painters and Sculptors, which famously exhibited (among other art styles) modernist 20th century works by Picasso, Georges Braque, Paul Cezanne, Henri Matisse, Wassily Kandinsky, Ferdinand Leger, Andre Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Marcel Duchamp, Constantin Brancusi and Alexander Archipenko. Modernist art embraced a number of radical movements such as Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism and others, and their common goal was to move away from realism and representationalism toward abstract art. This move was to prove highly challenging for many of the American public, who were used to realism and confused by abstraction. (For a short BBC video on the Armory Show and its impact, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJWLoXziXC4.) One member of the American public who was not distressed by the new abstract art was Williams, who was beginning to find his own poetic voice during this period, a period which had already witnessed considerable innovation and cross-fertilisation among the arts; in fact, the Armory Show was the single most important event that was to have far-reaching consequences for Williams. This exhibition, which was, according to John Hartz, ‘the most significant, improbable and iconoclastic art exhibit ever presented in America’, was organised to promote new developments in American art and with the Armory Show they intended to mark, as Walt Kuhn writes, ‘a starting point of the new spirit in art …and make the big wheel turn over in both hemispheres.’ This ‘new spirit in art’ was not lost on Williams, who immediately understood its implications for his own poetic art. As he explains in a 1963 essay: 'In Paris, painters from Cezanne to Pissarro had been painting their revolutionary canvases for fifty or more years, but it was not until I clapped my eyes on Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase that I burst out laughing from the relief it brought me! I felt as if an enormous weight had been lifted from my spirit for which I was infinitely grateful.” The enormous weight was the ‘encumbrance of traditional poetics and the dominance of the academies’. What was most attractive about the new forms which he saw at the Amory Show was that they suggested a more direct means of recording experience. For Williams, this meant the discarding of metaphor - or, in. his own words, ‘all the pretty glass balls’ - in favour of a direct engagement with the object and ‘one clear moment of perception’. Williams underlines the importance of this decision, when he writes: ‘The coining of similes is a pastime of very low order …much more keen is that power which discovers in things those inimitable particles of dissimilarity to all other things’. This stress on paying attention to separate elements, or ‘particles’ of objects rather than on their similarity to other objects (ie, metaphor), can be seen in his poem ‘To a Solitary Disciple’ (1916). Here, he begins by directing the writer (and reader) to notice how the moon is ‘tilted above/the point of the steeple/than that its colour is shell-pink …’ and to ‘…observe that it is early morning’ rather than that ‘the sky is smooth as a turquoise.’ Most significantly, the rest of the poem is informed by the important innovations that Williams discovered at the Armory Show, specifically those of cubism: Rather grasp How the dark converging lines of the steeple meet at the pinnacle - Perceive how its little ornament tries to stop them - See how it fails! see how the converging lines of the hexagonal spire escape upward - receding, dividing! sepals that guard and contain the flower! This poem bears witness to the fact that in a very short time following the publication of ‘The Arrival’, Williams was concentrating on a specifically pictorial approach to poetic form. The careful attention to the geometrical nature of the object, such as references to the ‘division’ of the ‘converging lines of the hexagonal spire’ - are a direct borrowing from both cubism and futurism. It is clear that, following the Armory Show, Williams’ verse began to give evidence of an entirely new way of looking at objects. ‘Seeing’, for Williams, (as Peter Halter has pointed out in The Revolution in the Visual Arts and the Poetry of William Carlos Williams) is ‘to perceive and feel the visual dynamics inherent in all forms and colours, and to assess the dynamic patterns that result from their interaction…an interaction which imitates the movement that flows through any work of art’. Williams did not regard his attempt at ‘seeing’ as a solitary venture: the reader of this poem is repeatedly asked to ‘grasp’, to ‘perceive’ and to ‘see’, and becomes as much the viewer of an object as the reader of a poem. Williams went on to experiment with many modernist art movements during this period, and one need only notice the dates of publication of these poems to comprehend the intensely exploratory nature of his ekphrastic poetry. These poems (most of which were published in Spring and All, 1922) truly reflect the energy and diversity within the world of the visual arts during the first years of the 20th century. It is important to note that various movements in the visual arts and literary arts did not (and do not) develop in isolation, and the modernist period witnessed a substantial overlap between the arts and their ideologies. It is not surprising that these are reflected in Williams’ ekphrastic use of paintings and their various styles. As Paul Mariani points out in his biography of Williams A New World Naked, ‘art, like baseball and medicine, was for Williams very much a team effort.’ That Williams saw poetry as an integral part of the art ‘team’ is evident throughout his verse and these are the innovations that helped ‘turn the big wheel in both hemispheres’ in art and in literature. Valerie Robillard Valerie Robillard was a lecturer in English Literature at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands (now retired). She is the author of The Ekphrastic Moment in the Poetry of William Carlos Williams (1999) and her website on ekphrasis (‘Poems Meet Paintings’) can be found here.

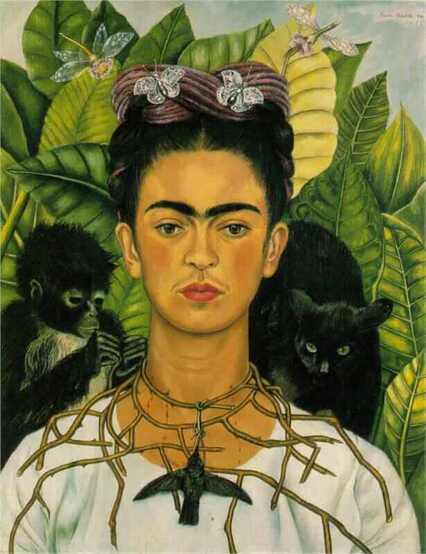

The Exhibition I keep my mind vacant as a new canvas. I want the exhibition to reveal my utmost desire, to tell me how to feel. It may destroy me, disfigure my body, I welcome the danger. The Curator accepts my signed disclaimer, and money transfer with a smile. Placing my right hand on the wall, I feel the thrum begin. Each finger vibrates, the pull of power is strong. My thumb stings with red, it tingles like the edges of fire. Index fingers feel blue, the chill caressing like waterfalls. Middle fingers prickle with yellow, dappled like a thousand dandelion serrated petals. The blackest of night flows through the ring finger. The smallest finger keeps the proportions of colour together, swarming into an eye watering whiteness. The paintings are warming up, flexing their muscles under their canvas preparing to be seen in their full glory, the Curator calls, good to go. I place my left hand on the wall, it is the controller, the artist, channelling the colour mixtures thrown at my senses. It keeps the vibrancy in check allowing me to hear, see and feel the works of the masters. I’m pulled into the wall. Leonardo greets me and sits me in front of La Gioconda. She smiles, revealing her white teeth and dimples. She has a bruise on her neck, a love bite or a pinch. Leonardo warns me with a wave of his fingers to pass this by and instead look into her eyes, linger in their enigmatic grace. She looks at me, into my future, beyond all that she knew. She closes her eyes, the knowledge in her face shines through. My own bruises whisper, longing to share our pain, but my time is up. Caravaggio appears, his Fortune Teller is looking into the eyes of a young man, his lust seeping from every pore. She smiles in deceit as she removes his ring, the reading of his palm a pretence. Returning his ardour, the rest of his money no longer in his pocket. She turns to me, looks into my soul, she knows her lies, I deny mine. Synapses unlock, paths rewire, I see my deception. Confession bites at me like a scourge of mosquitoes. Caravaggio hastens my departure, he has lies of his own to manage. Frida Kahlo, nods a welcome, her eyes bright, suspicious, but she nods to her Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird. She is her own self-portrait. Thorns pierce her neck. The sharp points twist in my skin, blood dripping, the monkey tightens its hold, digging the truth in further. The black panther bares its teeth, hissing bad luck. Frida looks away, I am not worthy of her time, my suffering is insufficient, my falsehoods spread too far. The curator bows as my hands are removed from the wall. Two hours have passed in a fleeting moment. I rest my worn-out hands in deep, gel filled bandages as the pain courses from my ruined fingertips to my arms, my heart, towards my hunger for forgiveness. I hope it is not too late. Joyce Bingham Joyce Bingham is a Scottish writer who enjoys writing short fiction with pieces published by Ellipsis Zine, FlashBack Fiction, VirtualZine, Funny Pearls and Free Flash Fiction. She lives in the North of England where she makes up stories and tells tall tales. @JoyceBingham10 |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|