|

Join Lorette C. Luzajic through a haunted house of terrifying artworks- and what wine to serve to Satan.

Wine and Art for Halloween at Good Food Revolution

0 Comments

Portrait of Alicia Galant

Alicia Galant, And two bright stars in the dark night, Categorised in Wikiart as Naïve Art or Primitivism, And yet, what an extraordinary expression On the beautiful face - A pair of eyes that seem to look deep Into the abyss of nothingness. Contrasting with the sense of futility and resignation, A suggestion of an inner calm, A hint of a light within That illumines the darkness without. Did Frida transpose her own soul Onto her friend's face, As she lay in bed convulsed with pain And struggled to hold her brush? Twenty years of age, Every bone in her body broken, Yet her spirit chose to find expression On a blank canvas, Not in vituperation against the tyrannies of fate. Pain transformed into art, Could there be a more sublime testimony To the resilience of the human spirit? Sandhya Krishnakumar lives with her husband in Amsterdam. An English Literature graduate and a teacher of French for many years, she currently spends her time reading, writing, learning languages and marvelling at the unexpected ways in which beauty and inspiration fill her days. Three of her poems are forthcoming in the Peacock Journal. More at: https://myeastandwest.wordpress.com/blog/ Notes on the Painting, Gas, by Edward Hopper

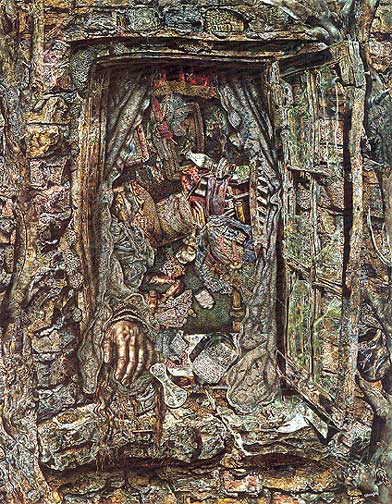

Dawn or dusk, the incandescent light seeps across the cement in pools with edges. A red winged horse flies like a flag above the scene but cannot move, except to rattle in the wind like a Model T. The attendant has lost his hair. He is dressed up for the task of keeping the pumps ready and the cans of oil displayed. Horses do not have wings, he may be thinking. He may be thinking of morning in a stable at a farm down the road, somewhere beyond the trees that hover in the distance, and of his mental inventory of the equipment of riding and hauling—harness, bit, stirrups, saddle, whip. He may be pondering the way his hands seem unsuited to the new forms of mastery, and how his world of service may disappear, just as the hair has already disappeared from his head. No one is on the road for now, but all the tools of loneliness and mental fatigue are laid in place. Mark Trechock Mark Trechock has been writing and submitting poems since 1974. He has lived in Dickinson, North Dakota since 1993, and retired in 2012 from the grassroots community organizing project, Dakota Resource Council. After a 20-year hiatus in writing for publication, Trechock resumed submitting his work last year. Since then, he has placed more than 30 poems in a variety of magazines, including Canary, Limestone, Wilderness House Literary Review, Badlands Literary Journal, El Portal, and Off the Coast. Three of his poems appeared in the book Fracture, a multi-author book on the impact of hydraulic fracturing in the oil and gas industry. Ivan Albright, to Whom I Keep Returning Ivan Albright, 1897- 1983, was primarily a painter, but he also kept detailed journals of his work and wrote poetry as well. His work appalled many and fascinated many more. He wasn’t interested in conveying familiar forms or notions of beauty. A lengthy essay on Albright by Courtney Graham Donnell begins with a poem of the artist (after which the essay takes its title) in which Albright reports: “A painter am I / Of all things / An artist who sees / the door and chair / And sees on the smooth things a flaw there / and sees on the round things a hollow there / And colors are not just colors to him…” Later in the same essay, Donnell quotes Albright revealing: “If I stir, [objects] stir. If I stand arrested, they become motionless.” These two fragments from the artist begin to unlock why I find Albright’s work so compelling. I first saw Albright’s work live at the Chicago Art Museum when I was a teenager. I remember being unwilling to move from his painting That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do (The Door). The painting enthralled me on multiple levels. First, the title intrigued me. I wasn’t used to artists who did more than hint at what their work was about or even distract from it through their titles. Albright’s titles tell part of the story of the work. (Of course, not wholly—he is an artist, and understands that the viewer/reader must also be allowed space to feel about the work. There must be enough loose threads that someone outside the work can pick up and tie to their own experiences.) His works bear names such as: Wherefore Now Ariseth the Illusion of a Third Dimension; And Man Created God in His Own Image (Room 203); Poor Room—There is No Time, No End, No Today, No Yesterday, No Tomorrow, Only the Forever, and Forever and Forever without End (The Window); Heavy the Oar to Him Who Is Tired, Heavy the Coat, Heavy the Sea. As an incipient poet, I was fascinated that a painting title could read as a compact story or poem. Next, the dates given for the painting, 1931-41, struck me. The artist took a decade to complete a single canvas. More than inspiration, that suggested obsession. This was an artist who was compelled to visit and revisit his work, to tell different parts of the same story, to approach it from all angles. Indeed, Albright has noted that he wanted to convey the way light “fragmented” his subjects as it hit them from all sides. For many of his pieces, Albright built three-dimensional mock-ups in his studio so he could circle around them, enabling him to add details to his paintings for years longer than any human subject would be willing to sit. This leads to the most compelling aspect of Albright’s work for me as a young person. His depictions were both arresting and horrifying—almost grotesque in their strangeness. Teens are learning that much about adult life contains just that mix of fascinating and frightful. They are acutely alert to ways in which surfaces misrepresent. They are still heavily undergoing socialization, that great falsehood in which they are told to act politely and strive for certain socially-permissible goals, while underneath, they know that what drives humans are baser, uglier, more selfish instincts. They are new to their sexualized bodies, which fascinate but also horrify. They are self-conscious about their hair, their skin, their symmetry (or lack thereof). Ivan Albright’s canvases showed that surface is an illusion, clean beauty is an illusion. He understood the multiplicity within us. He wasn’t afraid to look at ugliness and make it beautiful without hiding it or glossing it over. In fact, imperfection was the source of his inspiration. I was hooked. Albright tells writer Katherine Kuh, “For some time now I haven’t painted pictures, per se. I make statements, ask questions, search for principles. The paint and brushes are but mere extensions of myself or scalpels if you wish.” This claim resonates with me, now a poet in my own right, all grown up. My poems are extensions of myself—statements, questions, and investigations of principles. They are about the process as much as the product. Ivan Albright’s work inspires Ekphrastic poetry because it asks for multiple visits, begs multiple interpretations. Even reporting what the painter is doing is an elusive project. For example, when he paints wealthy art collector Mary Block (Portrait of Mary Block), is he celebrating her or gently mocking her? He conveys her strength of character, her wealth, and her command, at the same time that he makes her look menacing and ghoulish. Similarly, in his self-portraits, (specifically those from 1934-5), he places himself among desirable things in elegant clothes, yet manages to make himself look dissipated, like someone coming apart at the seams. The body of young female model in Three Love Birds has a youthful face while at the same time welling and bursting with the kind of bubbling accretions we associate with middle and old-age. All of this dissonance begs for a poetic response. Too, I appreciate Albright’s desire to separate himself from movements and labels. He was unafraid to be other, a “voice” of one for an audience of one. Susan Weininger’s essay, “Ivan Albright in Context,” quotes him thus: “To join some general movement in art …is to join a buffalo stampede. I say, let the artist be the hunter rather than the buffalo.” As someone who dropped out of an MFA program because of distaste for how Academia seemed to demand a particular voice and produce an aesthetic in almost cookie-cutter fashion, I embrace this independence of spirit. Similarly, in this internet age with its plethora of literary journals, it’s not clear if anyone at all is reading our poetry except for the editors who selected it and the poets who wrote it. One has to write primarily for oneself, interrogating existence out of a private and obsessive motivation. Finally, Albright models how I want to die. Four days before his own death, he created his final self-portrait (Self-Portrait 1983), a shaky line-drawing of his eyes, later made into an etching by John Paulus Semple. The body has all but gone, the life forced out of it, but the artist as witness, the vision of Albright’s singular intelligence, remain to the very end. That is what I hope for, to comment on my experiences until the biochemical mystery that makes me who I am ceases. Thus, I offer Ivan Albright as a source of inspiration to all who read this. One can visit and revisit his works endlessly without exhausting their narratives. Each canvas contains a world and its stories, whether depicting the animate or the inanimate. Nothing is as it seems. Paraphrasing Albright, every time we stir ourselves to examine them, the canvases come to life. One suspects that even after we turn our backs, they go on living and speaking—if only to themselves. Devon Balwit (All quotations and images referenced from Ivan Albright: Magic Realist, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1997) Devon Balwit is a poet and educator from Portland, Oregon, who learned to love art from her artist parents. Her poetry has appeared in numerous journals, among them: 3 elements, 13 Myna Birds, Anti-Heroin Chic, Dream Fever Magazine, Dying Dahlia Review, Emerge Literary Journal, Free State Review, MAW, Rat's Ass Review, Rattle, Red Paint Hill Publishing, Referential, Serving House Journal, The Cape Rock, The Literary Nest, The Yellow Chair, Timberline Review, vox poetica, and Vanilla Sex Magazine. She welcomes contact from her readers. Entering the Promised Land without Moses

I was just a child when we left Egypt. Felt the ground tremor – chariots charging after us. Run! Run! I couldn’t keep up. Uncle Joshua yanked me onto his back. We heard the hooves, the terrible whoosh! Water rose high in the air! A road cleared through the sea! Just as we scaled the bank, the sea crashed. I shook for three days. After that, I was frightened of Moses. What else could he do? But that changed when he came down from the mountain with the tablets. Only then did he yell at us. The elders were afraid, but not me. Something was different – his hair and beard gone white, but his face – more than young. He glowed like an oil lamp –a beacon I knew I’d follow. I didn’t know it would take forty years. My faith scorched and dried. Now it doesn’t seem fair. Here we are without him. Alarie Tennille This poem was written as part of the 20 Poem Challenge. Alarie Tennille was born and raised in Portsmouth, Virginia, and graduated from the University of Virginia in the first class admitting women. She became fascinated by fine art at an early age, even though she had to go to the World Book Encyclopedia to find it. Today she visits museums everywhere she travels and spends time at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, where her husband is a volunteer guide. Alarie’s poetry book, Running Counterclockwise, contains many ekphrastic poems. Please visit her at alariepoet.com. The Glass Painter

It was the Friday after Carnival Day, 1521, when I first met with Albrecht Durer, the most honoured guest of our guild. It was also the day they found the woman's body in the wharf. My master, and Dean of St. Luke's, Dirick Jacobsz Vellert, had travelled to Dilbeek on business. He was not due to return to Antwerp until the week after the Festival of Judiz. I was at my bench, poring over sketches for a rondel pane of St Alena when I felt a hand gently shake my shoulder. I should have sensed whose hand it was by the depth of silence that had befallen the other glass painters and apprentices. I'd no idea that Durer had been standing behind me, studying my work. "Come with me,” Durer said. I wiped the charcoal from my fingers and flung on my cape. Durer did not speak again until we were outside a print works, where he stopped to poke at the pavement with his stick. Around the gutter, where the apprentices tipped their buckets of ink-wash, ice crystals of many frozen hues built and grew as if vitrified. "Sir, is this what you wanted to show me?” I asked. "No.” He peered in though my eyes and it was as if my innermost thoughts and secrets were rendered clear and comprehensible to him,” You're skilled but your work is mimicry. How did you manage to conceal yourself in the guild for so long?” "Sir?” "How do you hide your breasts?” Despite the fierce cold my face burned and I shook. It was as if God Himself had called me out. "Well?” I stared at the frozen ground between his boots. "Straps…” When he led me down the wharf steps and across the ice I prayed a chasm might rent and the merciful waters engulf me. But his intention was not to expose me. A crowd of skaters and gawkers gathered in a semi-circle around the side of a merchant's fluyt. We pushed our way to the front. A market trader, with a brace of four chickens tied to her belt, knelt and wept. An old man, with a once-wise face, clothed in ragged finery, stared with a terrifying vacancy. The fool from the inn clasped his marotte; a heartbeat's echo, he tapped it softly against his chest, and for once he uttered not a word. The dead woman was frozen into the underside of the ice, her face in profile, a bloated arm hooked around the ship's anchor rope, her skin mottled and pale as white glass and grisaille. A frond of golden hair flowed from under her white bonnet and swayed in the current. Some murmured she'd been the mindless old man's wife. Durer took hold of my arm and spoke in whisper, ”I have a merchant from Cambridge, England, his client demands fidelity to the eye and alchemy of imagination. You will work in my studio, at night, under my instruction until your master returns. Are you willing to take the risk to know yourself, girl?” I nodded. Andrew Barnett author's note: "No one can agree who the artist was, although some speculate it could have originated from the studios of Dirick Vellert; he was the Master of the Guild of St Luke, Antwerp. If it had been painted in 1521, that was the year Durer visited and stayed in Antwerp, often as guest of Vellert. I found it fascinating to speculate, given Durer’s exposure to some of the more radical arguments of humanism in that year, if the artist who painted this image could have been a woman. There’s no historical evidence to suggest this might be the case but the idea of a 16th century female artist at the centre of the Lowlands Renaissance was too compelling not to explore as a fictional narrative." Andy Barnett is a student at the University of Cambridge in the Uk. Andy comes from a former mining village on the Nottinghamshire-Derbyshire border, which during the Ice Age, was the most northerly point our ancestors settled in Europe. He prefers manual jobs and working outdoors. He hasn’t set foot in an office for the last thirty years. He likes visiting Cambridge University because it is quiet and the buildings are surrounded by fields and trees. Next year, hopefully, he is going to step up to the MSt in Creative Writing and he would eventually like to study for a PhD. So far, Andy’s writing has been published in the Prague Revue and Zetetic: A Record of Unusual Inquiry. His visual interpretation of the work of the Romantic Poets was sold in greeting card format through the Tate Gallery in London. In-between his university coursework and writing flash fiction and short stories, he’s working on a gritty northern novel which is set in a former mining village on the Nottinghamshire-Derbyshire border. Dischord of Analogy

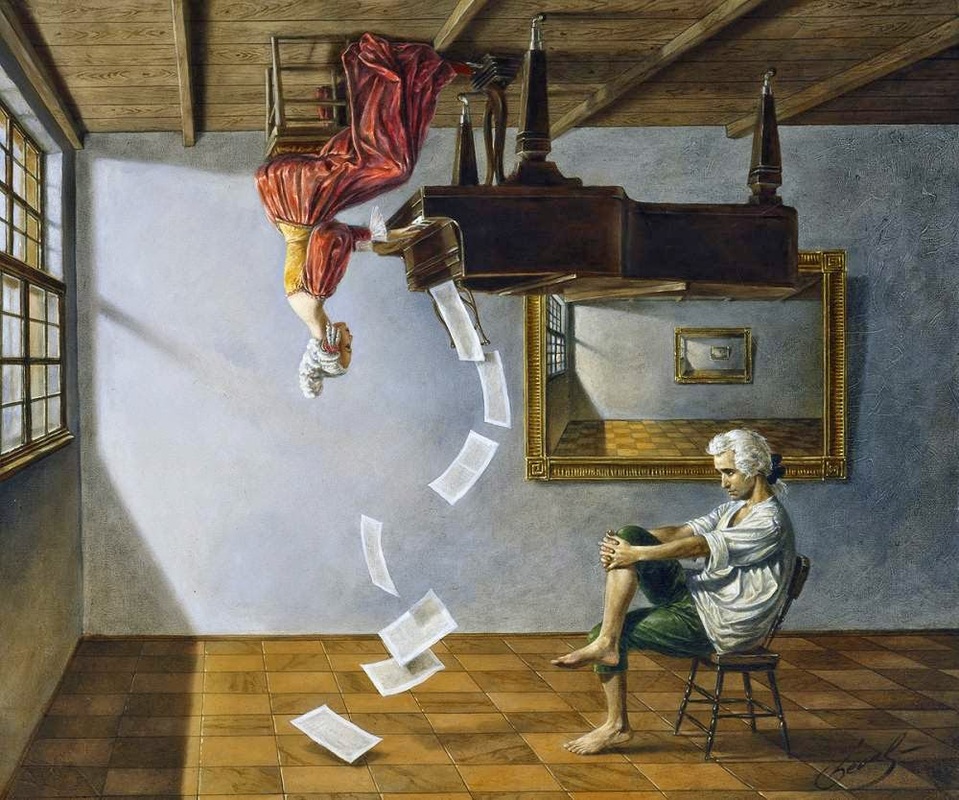

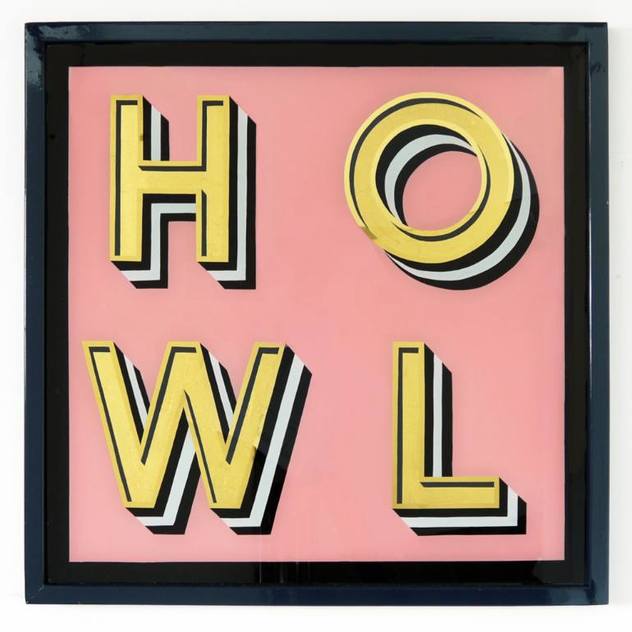

One fine, sunny day, they realized it was futile to go on pretending things would work out between them. Separation became an urgent necessity, yet neither he nor she had anywhere else to stay. After considering a number of options, it was decided she would move to living on the ceiling. Half the furniture, including the double bed and the piano (her most treasured possession), were moved up there as well. A light globe was inserted into the floor to provide illumination for the ceiling dweller. After an inevitable period of awkwardness and inconvenience, things returned to normal. He led his life and she hers. Although it would not have been very difficult for them to communicate, they each carried on as if the other didn't exist, just so they could maintain the illusion of privacy. This way, they could deny the fact that they were hanging above each other's heads and observing and judging one another's every action. The piano became the sole link between him and her. Its sound, refusing to respect the artificial boundaries, permeated the silence and spread equally to every point of the room…connecting, in spite of themselves, their senses and their souls. Thus, by a slender aural thread, their love did hang on. Separation eventually turned to reconciliation and an even stronger love prevailed. The piano became their conjugal bed. Boris Glikman Boris Glikman is a writer, poet and philosopher from Melbourne, Australia. The biggest influences on his writing are dreams, Kafka and Borges. His stories, poems and non-fiction articles have been published in various online and print publications, as well as being featured on national radio and other radio programs. Archie Proudfoot to Ekphrastic: "I like to think of my work as isolating language from the network of signs it represents and explore the emotional response that comes from that."

Visit him at www.archieproudfoot.com. Gloomy Day

Rejoice in the grey-gleaming gloom. Skies roll low enough for you to play master of your dirty-cloud domain—or is it smoke spilling from cautious chimneys? If all goes well, you will muster up a crass joke and get away with it, legs straddled wide as you laugh or spit. Until then, gather willow twigs to wattle a yard into a kingdom, a place to scatter broken crockery, a place for roosters to strut and for children to play at jousting. Thatch yourself a house, stoke the fire, stuff straw into your boots. February is short-tempered, and out of spite it could snip your fingers with frostbite or a careless blade. Think how unlikely it would be for this chill wind to blow in glad tidings. Better cast a leery eye upon the world, then gesture it to hell. Your paper crown makes you king for a day, and messengers are for other courts. Gut full of waffles and ale, you take a golden piss against the tavern wall, but the sky, more continent, waits for the dark before sending snow falling. Sleep in your village realm. Sleep dreaming of thatch, wattle, mullions, dark church glass, broken shutters, empty doorways, mud daub and shut gates. Olivia J. Kiers Olivia J. Kiers is an editorial assistant with Art New England magazine, and lives near Boston, MA. She holds a master's in the history of art and architecture from Boston University, and an undergraduate degree in French and fine arts from the University of Virginia. Her poetry and photography have been published in several reviews and zines, most recently Gyroscope Review, Bewildering Stories, and Sunset Liminal. To view examples of her artwork, please visit okayart.wordpress.com. Something Like Living

If an oil painted portrait is a second hand reflection a burlap sack is: the flatness of defeat grafted textile imprisonment startling sacchi They must have said pointing at the bloody rips in the cloth the sulfurous dust graining the corner "Here is blood washing up on the shores of Tripoli Mussolini's funeral shroud the skin of a dead monster!" But it is much more deliberate necessary even when One fingers the running stitches and crazy veins One feels the tired vital signs of a free man We all make art from what we know the pieces of our selves given by fathers jailers lovers and passersby they are the things we know crowding out the light of our day shouting us down they threaten to topple us over bury us And you knew bandages rough wool suits and laundry sacks the necessary pieces of your self to use anything more that's vanity The scars of prison the shredded linen and the aggressor the inhumanity of men I don't know this I am still fully on the other side of the wheel the slow upward ride of accumulation and satisfaction You shake your head if the victims ran the show there'd be no one left to share the dark tenuous stitches of our dizzy dreams crooked smiles and cracked faces in the thread you wouldn't have saved these scraps from the bin Everyone finds out what they are put together from that they are not colourfast some are only late to the show In the worn out places dirt clots in our scored surfaces I can almost smell the sweet decay of earth there almost see the gangly little flowers crawling through the cracks in our crumbled wall in early springtime These remnants flicker and fade when I turn to look: patchwork quilts and walls alike mean nothing in themselves they exist obedient to their purpose to settle for a quiet life longer than ours stand against time measure our ever changing now To keep some things out and some things in and let very few things pass between only a warm breath a single strand from a pale silkworm or the weedy green shoots of time Joe Boyle Joe Boyle earned his M.A. in creative writing at University College Dublin in 2013, where he edited the annual class anthology, Fault Lines. His thesis was a collection of poems called "The Innocents." He currently lives in Kent, Ohio, where he studies, reads and, at times, works. He can be found pushing pencils at an Akron block. He graduated from Kent State University in 2012, where he studied history, English and writing. Joe has been published online and in print in Bare Hands, We Are The Catalyst, Luna Negra, and the book for the 2012 Jawbone poetry festival in Kent, Ohio. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|