|

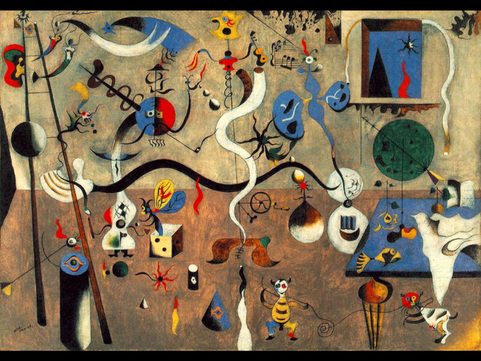

Miro’s Notebook I. Dusk, thus: a shirt drops, the bellybutton rune showing. Clouds are soaked, the sea now iron, muscle-heavy. The pond begins reflecting on astronomy. The fruit wait. The furniture call back their atoms. The tree asks for its leaves. II. Winter brought into the room is the whisk of holly. The purse is a hare limp on the table, its eye gone amber. The birdcage is the work I am after: bold-barred, so no bird leaves. The celadon throat, the iceberg teeth, the matted grass of an armpit . . . A pear, or maybe a stone, the chilled shoulder shifts under cover, not persuaded into similitude. III. In the snail-tracked sky, the mineral grains, a dozen eyes. You tell me thread is for seam and hem, not the mica bead-stitched on the dark. You refuse to have the shards the broom gathered be the moon, seen as aftermath. But like the thimble, I have no guile. So let your window open to the rain coming down, drumming on the hidden shells. IV. Black cherries. Glass of milk on a tablecloth. An arm of bread. The coins. Green scarab beetle. The compact’s sleeping mirror. The fig branch. The sundial. The harlequin leaves. V. Votive-light evening, cipher ridden. The marsh air, and my finger in places. Among the lesser constellations, the fractured kite, the anemone. The geese thread-pulled into the hard sleep. The clothespin, the gold in your hair. The seeds spread are a flung field. I sleep on stone, you on moss. VI. The red-haired figure in the station, the man selling carnations. The scarecrow landscape, the suitcases getting heavier with every stop. Those served as props. I dreamed we each played a part. One of us was given to say: I wanted your distance whispered down small enough for this room. And one to say: I saw you always just a little out of reach, with white hair. VII. A fish-scale moon: who doesn’t want to be left used windsock-hollow? Now for morning: the lit wick of each grass-blade, the saplings like legs of deer, the four walls verifying the house, and the slip of last night’s chive in your teeth. by Rick Barot from The Darker Fall, 2002, Sarabande Books, reprinted with permission of the author. Rick Barot was born in the Philippines, raised in San Francisco, and teaches in Washington at the Pacific Lutheran University. His third poetry collection with Sarabonde Books is due out this year. Barot’s poetry has also been published widely in journals including Poetry, Tin House, The Kenyon Review, and The Threepenny Review. It has appeared in anthologies like Asian-American Poetry: The Next Generation, Language for a New Century, and The Best American Poetry 2012. He is also the poetry editor of the New England Review. http://www.nereview.com Visit him at www.rickbarot.com.

0 Comments

This stunning painting of Sadko in the Underwater Kingdom is by Russian academician Ilya Repin.

From the Russian medieval epic Bylina, Sadko was a merchant, musician and adventurer who gained the favour of the Sea Tsar, who helped make him rich in a bet with some fishermen. Tragedy ensued when he used his gain without offering his respects to the tsar, and some sailors threw him into the sea to save their imperiled boat. Street in Venice

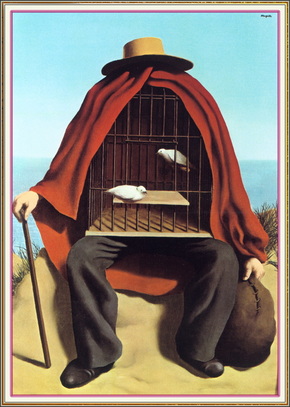

after a painting by John Singer Sargent This woman walks along the street with care, eyes downcast, black shawl gripped tight demure demeanor well portrayed. One of the men - the one propped casually against the wall – looks askance at her passing form. Is she an improper sort of woman or the right sort at the wrong place, the wrong time? Out too early or too late, no fitting escort in sight? Is her face too fresh, the flower in her hair too brash? Does the flounce of her white gown ride high as she walks, promising a glimpse of slender ankle? Is it simply in the nature of men, some men, to look askance? by W.M. Herring W.M. Herring graduated from UBC (Vancouver, BC) with degree in Honours Computer Science. She now runs a B&B on rural property near Prince George in north-central BC. Her work has appeared in several publications including ARC Poetry, Literary Review Canada (LRC), The Nashwaak Review, Christian Century and Queen’s Quarterly. What is the Artist Trying to Say? Nothing, Magritte Claims

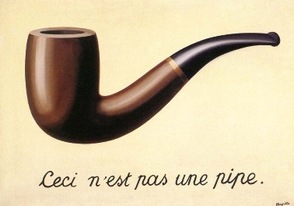

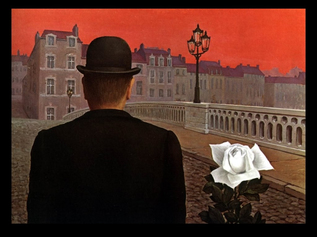

Magritte’s paintings are overflowing with recurring images and eerie objects that we naturally grasp at as symbols. But the artist rejected symbolic interpretation of his work and asked us to avoid deciphering them in this way. "To equate my painting with symbolism, conscious or unconscious, is to ignore its true nature,” he said famously, thus thwarting professional and armchair critics alike from claiming any expertise on what the artist was trying to say. Magritte’s painting, Pandora’s Box, is just begging viewers to try puzzling out what he intended to convey with a blood red sky and a stark white rose. And there’s that man in the bowler hat again, bearing a striking resemblance to the artist himself, even without a face What is this man always looking at, or looking for? One commenter online, oblivious to Magritte’s muzzle against meaning, read the sky as war and the man facing the empty streets as the isolation and loss that haunted the world after WW2. The white rose represented the hope for peace. The rose, the lamppost, the balustrade, the bowler hat. We see particular objects again and again throughout Magritte’s paintings. “…Magritte created enigmatic pictures of flying boulders, burning tubas, giant apples trapped in rooms, or rainstorms of stolid businessmen falling on towns,” writes art historian Camille Paglia. “Typical Magritte paintings show a water glass precariously perched atop an airborne stone balcony.” Magritte plucked the ordinary markers of existence, everyday objects, the humdrum and banal, out of reality and twisted them into scenarios from The Twilight Zone. But he ties our hands behind our backs, refusing to give us an escape route in “figuring it out.” If only we can decode something, if only it’s meaning can be revealed, then we would no longer be snared by our surreal confusion. This of course, is the conundrum of life itself- man’s search for meaning, as they say- but even in saying so, I veer perilously close to symbolism again. Magritte said, “People are quite willing to use objects without looking for any symbolic intention in them, but when they look at paintings, they can't find any use for them. So they hunt around for a meaning to get themselves out of the quandary… They want something secure to hang on to… By asking ‘what does this mean?’ they express a wish that everything be understandable.” Magritte said that viewers “who look for symbolic meanings fail to grasp the inherent poetry and mystery of the image.” He felt that, “No doubt they sense this mystery, but they wish to get rid of it.” I stand forever enchanted in the evocative corridors of Magritte’s imagination, with no need to nail down a particular code. But I do think Magritte’s insistence against interpretation is, like his paintings, something of a mind game. After all, the infamous pipe that wasn’t a pipe was not a pipe because it was a representation of a pipe. You couldn’t smoke it, of course, but nor could you deny that it showed the aesthetic, visual properties of a pipe. It was, therefore, a symbol of a pipe. Literal symbolism in painting traditions often meant stand in signifiers- a dove represented the holy spirit, the snake represented Satan, a rose represented romantic Eros, and so on. So it is understandable that we might wonder whether the painted pipe symbolized an actual pipe, or something else. A particular colleague who smoked a pipe, perhaps, or a penis, if Freud is our guide. Even so, I don’t think most Magritte viewers are looking for literal translations. Magritte may have felt that “reducing” his work to symbols was missing the point, but his continued harping on the viewer’s weakness in longing for meaning was no doubt part of his strategy. His paintings are conundrums, even if they don’t have a specific, correct key to a-ha. When considering his “anti-symbolism,” one must also take into account that Magritte did not like to be called an artist. He was, rather, a thinker who painted. These kinds of curious philosophical mind games reflect Magritte’s droll humour and imaginative genius. His interest in chess and cinematography also make sense in light of the peculiar visual staging and seeming puzzles of his work. Magritte was concerned with mystery and poetry and sought to evoke these through juxtaposition of quotidian objects and scenes. Still, to reject entirely the historical and social context of his artwork would be foolish. He painted through the decades of the ‘20s to the ‘50s, a time where the unconscious played a starring role. Freud’s impact was profound; then, his ideas about dreams, subconscious drives, sexuality, and human nature were tempered (or tampered) by his student, Carl Jung. Both of these brilliant men asked questions and uncovered truths about the human psyche, from the sinister to the sublime. Their approaches differed but ultimately we owe an enormous debt of what we understand about the mind to both of them. These radical shifts in understanding human nature and relating to the world prevailed in the very essence of Surrealism, the ism to which Magritte belonged. And although he was always reluctant to be labeled in any way, the intellectual and social climate of his era and his associations make it impossible that these ideas played no role in his work. Thomas Moore, psychotherapist and philosopher, perhaps expresses the “meaning of Magritte” in his therapeutic worldview that life is not a problem to be solved or fixed. We must live with the paradoxes, for they are integral to our soul. Magritte, he says, “understood more than most that our way of connecting things is not as rational and linear as we imagine.” It is a further irony that Surrealism, the art movement to which Magritte was most closely affiliated, was also in part an heir to the Symbolist movement the century before. Symbolists and Surrealists shared the objective of looking beyond the rational and material for meaning. While recognizing Magritte’s genius for freethinking, I believe it’s also safe to conclude that the painter’s stance against symbolism was a little game of its own, a semantic hustle to make us think and respond more carefully to art by considering our confusion. The best way I can approach Magritte’s art is this: Magritte’s rejection of stand in signifiers- of fixed symbols- cannot mean his audience will not find connection, sublimation, or meaning in his work. A dream dictionary is useless, despite dedicated devotees, and in this way, decoding Magritte according to fixed interpretation is futile. Freud saw a dream about teeth falling out (or a dream about anything else, for that matter) as representing sexual repression. Jung saw anxiety or loss. The theatre of our unconscious is necessarily dependent on our own set of experiences, not just our animal nature. A tooth in one man’s dream is not the same as a tooth in another’s. It could mean pain to a particular person, but even if it recurred, it might now reference instead a memory of a stranger’s smile. The dream dictionary approach to both symbols and to dreams is facile. Meanings are not fixed. Symbols are fluid. Magritte is right that trying to pin these things down is a ludicrous attempt at chipping away from mystery with lousy, primitive, tools and very little in way of imagination or context. But imagery’s very power is the narrative it inspires and the resonance it meets with in its viewer. Magritte’s apple or egg or train or clock may not substitute for particular, intentional alternatives (like “original sin”, “birth,” “speed,” and “time”)-but they will evoke intense and unique associations for different people. “'My images are not substitutes for either sleeping or waking dreams. They do not give us the illusion of escaping from reality. They do not replace the habit of degrading what we see into conventional symbols, old or new…” Be that as it may, only a dead man can approach a Magritte without a whole cascade of illogical, beautiful, eerie, nostalgic, provocative narratives spilling from one’s interior world. Without this effect, there would be no power in the paintings at all. They are compelling precisely because they take us deeper into the profoundly symbolic space of our unconscious. But of course, Magritte knew all of this very well. "The mind loves the unknown," he stated. "It loves images whose meaning is unknown, since the meaning of the mind itself is unknown." Lorette C. Luzajic Camille, at the end

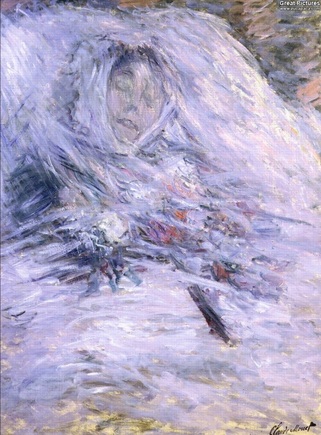

I am too weak to stir, my love but I can hear the whisper of your brush stroking the canvas. I can't bear to think what I've become, what you are seeing. What light is left in me that you can illuminate further with your hand? But I am what I've always been to you, a muse. A body, a face, to contemplate. In our short history we've been many things. Shared many kinds of love. Not all bliss, yet no other life would be better. Remember that time, mon amour, when you and Auguste stood strong shoulder to strong shoulder breathing in the scent of grass and youth? Studying the sky? The blues and greens. The shape of my hands clutching a bouquet of wildflowers. Remember how safe we felt, in the afternoon heat? How we talked about our thirst, all the way back through the field? How we dreamed of water and chilled wine and the wet cool on our lips? Remember how you laughed when Auguste stumbled and nearly dropped his canvas? His gaze trapped, skyward, watching the birds. We were so free to love and live. Yet, wouldn't I still be here, withering from my womb, passing into a realm without you? Wouldn't I still be a mistress? A mother? A form for you to build and rebuild with colour? My eyes have goaded you into creation. Into repute. Into sorrow. I know you will mourn me. Know you will remember my face in all our histories. You will not wear this grief long. Will find new radiance in the sun on calm water or the fog through the trees at quiet grey dawn. I know you will teach our sons how to seize what is beautiful in this life. How to see what's beyond the eyes. How to love with every sense. I am ready to leave, my love. Young, but not untested. I have been la dame dans la robe verte. I have been au coeur de ma famille. I have been. With you. by Kim Mannix Kim Mannix is a poet, journalist, wanna-be horror writer, mom, wife, hypochondriac, music nerd, TV snob and feminist who has lived in seven Canadian cities and has decided to stay for awhile in Sherwood Park, Alberta. www.makesmesodigress.com I worry constantly about my eyes. I embrace my eyewear collection, spanning cool couture to Jessica Fletcher, but am furious at my dependency. And I get angry having to take them off to read and put them back on to see more than a foot in front of me.

I feel as if I have just recently begun to be able to see, and yet, at the same time, my eyes are failing me. I need to be able to look. I panic about future deterioration and catastrophize about going blind. That I have resolved to jump off a cliff if my eyes fail me is both pathological and childish, but speaks to the intensity of my obsession. I don’t take my eyes for granted, not for one day, not for one second. I cannot live without looking. I make sense of the world visually. I take in the most information with my eyes. I have always loved reading, for which the eyes are the key technology. I process best through reading or watching, not through listening. I can listen, but processing what I hear is laborious. I don’t attend many poetry readings anymore because I find sitting through readings insufferable. The poems are usually ruined. I am moved most by savouring the texture and shape and meaning of the words on the page, soaking in the sweet contrast of the marks against space, looking at the weight of the words as they make their way into my soul. Our visual receptors are not simply tools or techniques to absorb information- they are my most important source of sensuality and pleasure. How I delight in gorgeous women or unusual colour combinations! The aesthetic of both lean and serene minimalism and the eccentric, clunky cacophony of clutter have equal appeal. There is beauty everywhere I look, and I cannot live without beauty. I spend my whole life looking. Not at anything in particular, but at everything. For answers, yes, and sometimes for things I’ve lost. But mostly, just looking. It is obsessive, the number of images I go through. It is hunger. I look at art and photography in books, in galleries, in museums, on Pinterest and on Saatchi and on Google. The originals are best, but books can take me all over the world and the internet is up to the minute. My own library of art books would take a whole life to properly explore. But there is more out there, more. The online universe is witchcraft really, with its miraculous instantaneity. Books are magic, too, populated by the very spirits depicted in their pages. I have a stack of coffee table books on Marilyn Monroe. I never tire of looking at her beautiful face. Sometimes I make a point of not looking at her face. It is a revelation to see how fully she conveys everything with her body. Even if she had a paper bag over her head, she would be perfect. Monroe is as gifted as a dancer in what she is able to show with line and curve and movement. Sometimes I leaf through the photos and look only at her hands and feet. She conveys a fluid elegance in even the most candid shots, her hands like Buddhist mudras or the chironomical gestures of Orthodox icons. Today I looked at Egon Schiele, a book I picked up at a Taschen sale. I have always been repulsed by the putty and bruise pallor of Egon’s subjects, and by the raw edge of his disgust. But lately I have found his paintings increasingly compelling. There is an unbearable sadness in their temporality. The compulsion and revulsion Schiele had for the human body is heartbreaking in hindsight, with the merciless punctuation of death, which took him and his wife and her unborn baby, via pandemic influenza. He was 28. The ick factor is also strong with the work of Joel-Peter Witkin. He uses actual dead bodies to create the assemblages for his photographs. This extravagant flouting of taboo seems hideous and perverse, but there is a compelling beauty in how he refuses to turn away from what we pretend not to see, what we pretend not to be. The corpse has a longtime role in art, of course, as a teacher of anatomy, or as the practical matter of fact that it is. The great Caravaggio did it- he also used corpses as models. I did it, too, I went to a medical cadaver lab to view an array of grisly and dissected bodies, the insides of ourselves, death without caskets and suits and powdered pretensions. It was something I had never seen and something I had to see. Now do you see? It was horrible, this fleeting, rotting truth about ourselves. Even our eyes rot. Our fear there, our decay, for me to come to terms with and touch and see. Looking, looking. Also today: wild textured abstract paintings, and parchment, buff, eggshell, a whole rainbow of off-whites. And Monet, too. Monet, soft and fuzzy, the antithesis of Schiele, sharp edged and rough. But both men, obsessed with looking. I thought about eyes a lot on my recent voyage to Israel and Jordan. I was thankful every second of sight. The clatter of the crowded souk and the hush that fell over the night Dead Sea also held sensory magic, as did the cloud of spices rising over grilling lamb- but without my eyes, I thought quite often, what would be the point of travelling? I could climb to the top of the Masada, but for what? To listen to the dusty silence of forever below without seeing its vast reach beyond me? I could hear a few goats go by but not see them fleck the desolate landscape with life, and what would be the point of that? I took in countless things. I could not understand how some used the bus ride to snooze. That meant closing your eyes! I tried to look out of the windows on both sides and the front, too, with my cameras clicking to capture a fraction of what I saw. How the rose gold morning turned to sun-bleached grey on the stones of the Jordan desert, how the saltiest sea is just a pale pink mist right before dawn. The faces of Nigerian pilgrims were round and dark; the tealights in the churches glittered gold against the ancient icons. And lemons, sunny yellow against the bluest sky. And what else? Brass, bronze, silver, lapis lazuli, red coral, carnelian, turquoise, etched, engraved, carved. Almond trees, bananas, date palms tall and lanky against stark and endless landscape. The rough bark of ancient olive trees. Crumbling ruins, the scars of history, ageless stone worn smooth under a hundred thousand thousand footsteps. On some days of my journey, my eyes literally ached from taking it all in. There was so much to see that at some points, the overload meant it wasn’t computing anymore. This phenomenon happens to me often at art galleries. There are points where you simply can’t see what you are looking at anymore. And that’s precisely what I fear most for the future. Without images, I will be a crumpled can, a dry husk, not a poet, not an artist, not a photographer. Without what I see, I will be empty. Lorette C. Luzajic www.ideafountain.ca Art

In placid hours well-pleased we dream Of many a brave unbodied scheme. But form to lend, pulsed life create, What unlike things must meet and mate: A flame to melt—a wind to freeze; Sad patience—joyous energies; Humility—yet pride and scorn; Instinct and study; love and hate; Audacity—reverence. These must mate, And fuse with Jacob’s mystic heart, To wrestle with the angel—Art. Herman Melville |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|