|

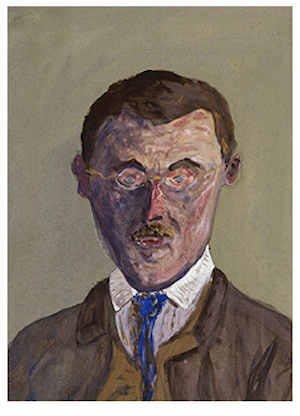

Salieri, after a performance of Mozart’s The Magic Flute at Freihaus-Theater auf der Wieden, October, 1791 The cheap seats love the man. Each night he lures them from slogging streets into the pomp and pageantry of fairy tales with music that makes the angels cry. They love the oboes courting flutes, bassoons entwined in clarinets; strings outracing trombones, trumpets, tubas, horns toward kettledrums shuddering the boards beneath their feet. They care not for scores or virtuosity. They want delight— magic doors, scenes that fly, finales—and more, und mehr. I hide behind red drapes high above the crowd, and watch them watch the note-barrage shooting from his fingertips. And when the coloratura soars toward F above high C, I catch them catch their breath before their “Bravos!” seize the chandeliers where magic drips from candle wax. The pulse-throb of the aria vibrates my skin. I want to cry. Divinity has voice. But when the curtain falls the deafening applause unhinges me. “Encore! Encore!” reminds this lesser child of God, he’s fated second-best. Heaven-hurt, I never could compose so many notes across a page; never could raise a mundane crowd above its seats as that little man with fire in his fingertips. by Carolyn Martin Previously published in Carolyn Martin, Finding Compass (Portland, OR: Queen of Wands Press, 2011). Used with permission of the author. Carolyn Martin is blissfully retired in Clackamas, Oregon, where she gardens, writes and plays with creative friends. Since the only poem she wrote in high school was red-penciled “extremely maudlin,” she is still amazed she continues to write. Her poems have appeared in publications such as Stirring, Persimmon Tree, Antiphon, and Naugatuck River Review. Her second collection, The Way a Woman Knows, was released in February 2015 by The Poetry Box, Portland, OR.

1 Comment

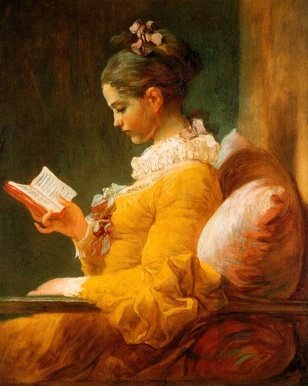

And Simply Read

But if the body were a kind of book… Karen Fiser Imagine it as a rectangle, small enough for a hand to circle, lift from the table, slight enough to bear from chair to bath, to steady on the rim of a tub, to skim to the end of leafing ahead to the obvious while around you steam rises. Or suppose a more complicated plot, one that prods you to locate the chapter on desire, intention in the author, one you could explicate. Lay that one beside you on the bed. Let it fall open of its own accord and simply read. by Wendy Taylor Carlisle Wendy Taylor Carlisle lives in the Arkansas Ozarks. She is the author of two books, Reading Berryman to the Dog and Discount Fireworks (both Jacaranda Books). Her most recent chapbook is Persephone on the Metro, (MadHat Press, 2014.) For more information, check her website at www.wendytaylorcarlisle.com. The title of this painting collage is from a line by Haruki Murakami, in his short story "Lederhosen," from The Elephant Vanishes.

"Brightly Coloured" an illustrated poem by Ariel Rainer Fintushel, is a response to Chagall's autobiography, My Life.

Ariel Rainer Fintushel currently lives in Los Angeles, California, writing and making comics. Ariel is working on a book about a female skydiver from the 1900s, and has recently been published in Baltimore University's Welter, Dali's Lovechild, Shabby Dollhouse, and Defenestrationism, with a poem forthcoming in Bop Dead City. An Iceberg Lived

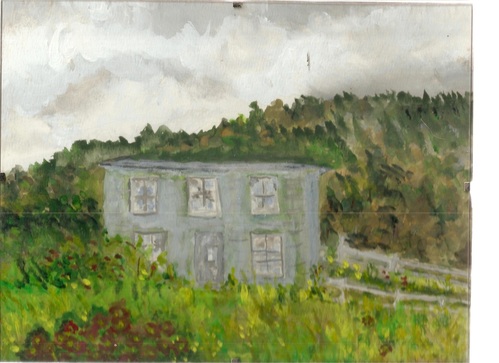

In Twillingate I rented a house on the North Side with threefold dormer windows watching over a picket fence cradled lilac tree In spring the upstairs bedroom felt like a ship at sea floorboards sloped to the east window where, in the harbour, an iceberg lived In winter the ocean current corralled a herd of jagged ice pans and the house walls, undefended, allowed the north wind Cold swept up the staircase snow grains lashed the windowpanes and the old house, glacial, became a tomb Timbers shuddered day and night, and wretched I left my coat on went to bed after supper In summer I moved house abandoned the vagrant dust wisps plugged kitchen sink, and ajar garden gate But I dreamed of islands and icebergs parlour doors that opened to sea water, and Years later I returned to find the threefold dormer windows boarded fence broken tree wilted, the house diminished withered more alive shining in my dreams Joan MacIntosh Joan lives in St. John's, Newfoundland and writes poetry, fiction and essays, paints and journals. Her poetry has been previously published in TickleAce, Leafpress, Newfoundland Herald, and other publications. She finds that simple visual images find themselves in poetry and paintings and often discovers haiku through journal writing. I Want to Be An Insect

I want to be anything but the thing I am an insect first and last to live even for just a day in a post-apocalyptic world without a human sound a soldier in an army of the ants a worker for the queen of bees to fly (with wings my own) to crawl (not on my knees) to suck the nectar of a god or be the god of butterflies I want to be anything but the bug I am. Neil Ellman Neil Ellman, a poet from New Jersey, has published numerous poems, more than 850 of which are ekphrastic, in print and online journals, anthologies and chapbooks throughout the world. He has been nominated twice for the Pushcart Prize and twice for Best of the Net. Aree’s Abstract “To encourage spots and blobs he tugs the ear forward, towards the canvas. So, very sadly, the design the elephant is making is not hers but his. There is no elephantine invention, no creativity, just slavish copying.” - Desmond Morris, Daily Mail, February 21, 2009 Aree watched her mahout approach: his long metal hook resting on his shoulder, his gnarled, leathery face pinched in a scowl. He grabbed Aree’s ear and led her past a young elephant tied up between four wooden posts. Dried blood covered the elephant’s face, and his trunk hung low. As the mahout passed, he swung his hook in a lazy, half-hearted motion striking the elephant on his back. Aree had been “broken” like this too long ago. She turned her head away so as not to lose resolve for her planned insubordination. The mahout led Aree through the bamboo forest which shrouded her grim accommodation from tourists. Next, they walked down the tunnel, one side clear plastic glass, the other side a cinder block wall wheatpasted with prints from Van Gogh, Munch, Picasso, Klimt, Hopper, Homer, and others. Aree once had a young mahout who’d talked about those paintings as he led her down this chute, a daily, 100-yard art education. The tunnel opened up into a larger paddock. Aree approached the easel set up there and faced the steel-cable fence and the tourists beyond it. The mahout grunted and handed her a paintbrush loaded with black. She hated the necessity of this, that despite her aspiration and talent, she wasn’t physically able to pick up a paintbrush without human help. Aree heard the familiar low-level chuckle from the audience. The mahout tugged her ear. A small nail hidden in his palm dug into her skin and guided her to the starting point on the canvas. She painted the same thing every day: two elephants trekking through a field of flowers. She used simple, representational outlines for the elephants, short brush strokes for grass, and specs of color for flowers. The mahout’s hook hovered above. His nail tip pinched the back of her ear and guided the arc of her lines. Aree recognized the paintings on the cement tunnel wall as comedy through juxtaposition. How many human painters were there? She assumed many. Only a population rich with artists would laugh at the folly of an elephant trying her hand at this lofty human endeavor. Extrapolating from the small sample of human work she’d seen, she imagined a near infinite number of artistic styles and longed to create something of her own. Aree had never seen a field of flowers like the one she painted daily. Her compound looked raw and dusty. The captive elephants imprisoned with her wore their plight in the form of complex, wrinkled, scarred, and fragmented faces. Deep, severe lines. Picasso’s cubism mixed with the dark outlines of Van Gogh’s trees. The mahout tugged down on Aree’s ear, a signal for her to complete the downward slope of her subject’s trunk. Instead, she closed her line to make a small rectangle. The mahout mumbled, then smacked her back with his hook. He tore the paper off the easel and hung a fresh sheet. He grunted, reloaded the brushed, handed it to her, and pulled her ear hard, his nail digging into her skin. Again, Aree began the slope of the trunk, then made the sharp right angle of a rectangle. The mahout struck her three times. She wanted to paint a piece that showed the depth of her experience. She’d already composed it in her head and needed materials and space to realize her concept. The mahout reached to tear off the paper again, and Aree swung her trunk and pushed him out of the way. He stood back wide-eyed looking at her from shoulder to toe as if noticing her enormous size for the first time. She added several more lines, the amalgamation of rectangles began to form an elephant face refracted and reimagined. The mahout yelled and raised his hook high. Aree kept painting and stomped her foot twice hard and heavy. The ground shook. The mahout quieted. The crowd gasped. She reloaded her brush and made dark, heavy lines. She felt the mahout approaching from the side. She turned to face him, and while instinct told her to trumpet a great sound of warning, she didn’t want to drop her brush. Instead, she grunted and made a sudden move with her head as if she were about to charge. The mahout froze giving Aree more time with her canvas. She worked furiously knowing others would soon rush in, beat her, sedate her, or dole out whatever punishment deemed appropriate for an elephant breaking from realism and delving into abstraction. She didn’t have time for the self-critic. Instead, she marveled at the waterfall of shapes spilling down her paper, hard edges that together made the gentle slop of an elephant’s trunk. Her subject’s eyes looked wise and hard between her clean, angular lines. She heard murmurs from the visitors beyond the fence but stayed focused on her work. Then, out of the corner of her eye, she saw seven men approaching. They carried rope, hooks, a dart gun, and an electric prod. If she could finish painting the head and face of her portrait, that might be enough. A few simple lines suggested the outline of the body already. The men surrounded her. She stepped back and looked at her canvas. In it, she saw all her influences — the posters she passed daily, her life experiences — and she was satisfied. Next, she felt a jolt of electricity shoot through her. She’d once heard a trainer say an elephant has 40,000 muscles in its trunk, and she thought how this elaborate interwoven systems of nerves and small muscles had to be more complex and nuanced than human fingers. In those 40,000 muscles Aree imagined potential for new techniques, new brushstrokes. Now, with the pulse of the electric prod, her trunk muscles stiffened, and she dropped her brush. A sharp pain pierced her neck and she turned to see a man lowering a dart gun. A moment later, the tranquilizer took effect. Her legs gave out. She sank to her knees, and her vision blurred. A man threw a canvas bag over her face. With much effort, Aree lifted her head and pushed the bag from her eyes with her trunk. She took one last look at her work. Her mahout took the paper off the easel and looked at it quizzically. Then, he tore it in two, the sound an audible end to Aree’s experiment in abstraction. She gave in to the tranquilizer and let her head fall back to the ground. She wondered if there were any artists behind the steel cable fence with enough empathy to understand what she was feeling. by Theodore Carter Theodore Carter is the author of The Life Story of a Chilean Sea Blob and Other Matters of Importance (Queens Ferry Press, 2012). His fiction has appeared in several magazines and anthologies including The North American Review, Pank, Necessary Fiction, and A capella Zoo. Carter’s street art projects, which began as book promotion stunts, have garnered attention from several local news outlets including NBC4 Washington, Fox5 DC, and the Washington City Paper. www.theodorecarter.com Le Comte St Genois: Christian Schad

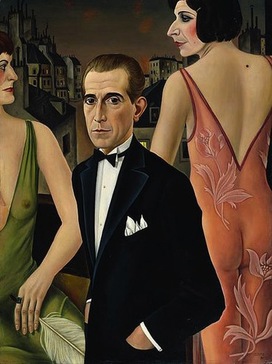

Le Comte can fool us, French Lieutenant in a tux, his sleek hair, blinding pocket square, his ladies’ lethal kohl-eyed stares, their bodies visible through gauzy peau de soie, pink leaves, are sexy, rose et vert. They have, this group, three noses from which to look down on us. Behind them, Paris, Berlin, any New Objective city, lurks and looms. They stand apart and glow. Are they translucent, shining, meant to gather an admiring view, or are they vacant and transparent, prisoners of their hauteur and ennui. by Wendy T. Carlisle Wendy Taylor Carlisle lives in the Arkansas Ozarks. She is the author of two books, Reading Berryman to the Dog and Discount Fireworks (both Jacaranda Books). Her most recent chapbook is Persephone on the Metro, (MadHat Press, 2014.) For more information, check her website at www.wendytaylorcarlisle.com. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|