|

Exclusion Zone after Untitled Film Still #33, by Cindy Sherman (USA) 1979 https://www.moma.org/collection/works/56708 Even though she’s alone, she invites us into this generic bedroom with a double bed and rumpled bedding. This trespass has the smell of musk and men’s cologne. It lubricates the scene. Her hair is curly and cropped in a bouffant hairstyle. Her glasses are pink horn-rimmed cat eye. A sleeveless mock turtleneck in a subdued paisley print, pedal pushers, white bobby socks, and pastel penny loafers complete the look and register a timeframe of late 1950s. There’s an envelope with a letter laid out in the centre foreground. Placement directs us to believe that this is the most important element—the tip of an action triangle. She’s withdrawn to the right side of the bed near the headboard as far away from the letter as possible. Her right arm recoils behind her like she’s touched something toxic. She sits off balance with her legs drawn sideways—sidesaddle if she was on a horse. The brightest light comes from an outside source like sunshine through a window. It highlights her right calf, ankle, and foot. Her body seems precariously balanced on toe point, but she is grounded in this clarity. Her left arm and splayed hand steady the twist in her upper body. Our eyes follow the headboard across to the bedside table and a table lamp with a single naked lightbulb. In this lesser light is a framed portrait of a man wearing a tie, an older man with grey hair. He’s the third anchor point in the photo. Do we side with her or with him? A few holes in the wall plaster behind her, and the stark lighting helps us navigate the dichotomy. ** Entering the Fallout after Untitled Film Still #10, by Cindy Sherman (USA) 1978 https://www.moma.org/collection/works/56555 We’ve caught her in another awkward moment, scooched over a ripped brown paper grocery bag. She looks up but not directly at the camera. The side-eye glance suggests someone else is present. Campbell soup cans, plastic Blue Bonnet margarine tubs with flowers on the side, a jar of mustard, and a carton of orange juice lie discombobulated on the floor. She’s dressed in a mod flower mini skirt and over-the-knee boots. Her hair is a shaggy medium-length bob with blunt bangs. The makeup is period 1960’s with thick-winged eyeliner, black mascara and matte eyeshadow, nude lip polish over her lipstick. Her bare thighs form two sides of an action triangle at the center of the shot. The carton of extra-large eggs clutched in her right hand is the right length to be the third side of that triangle. Did the eggs survive unbroken? Maybe the chenille throw rug broke their fall. On her right forearm there are two pale bruises. One is shield-shaped and larger than the other. In black and white they’re a subtle shade of grey. With the rest of the shot so carefully considered, this element isn’t accidental. It’s a pivot point. Yet many of us will miss that detail along with the tiny rose sticker on the oven door. She looks up from this disaster with her coat still around her shoulders, a carapace of protection. It cleverly covers the wire of the camera’s remote shutter release with its push-button trigger. Cherie Hunter Day Cherie Hunter Day lives in the San Francisco Bay Area among some thirsty redwoods. Her work has appeared in Mid-American Review, Moon City Review, Rust & Moth, Unbroken, and been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and Best Microfiction anthologies. Her most recent collection, A House Meant Only for Summer (Red Moon Press, 2023), features haibun and tanka prose. When not writing poetry and micro prose, or making collages, she is outside cleaning up after the aforementioned redwoods.

0 Comments

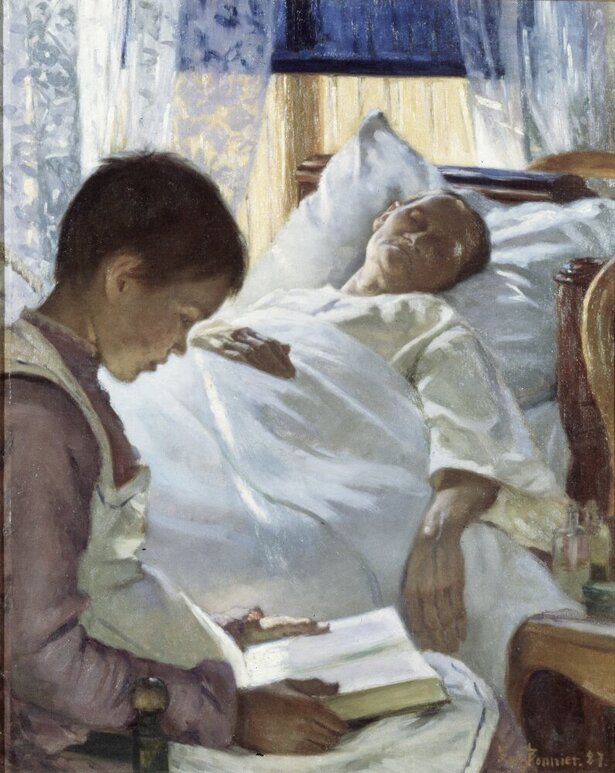

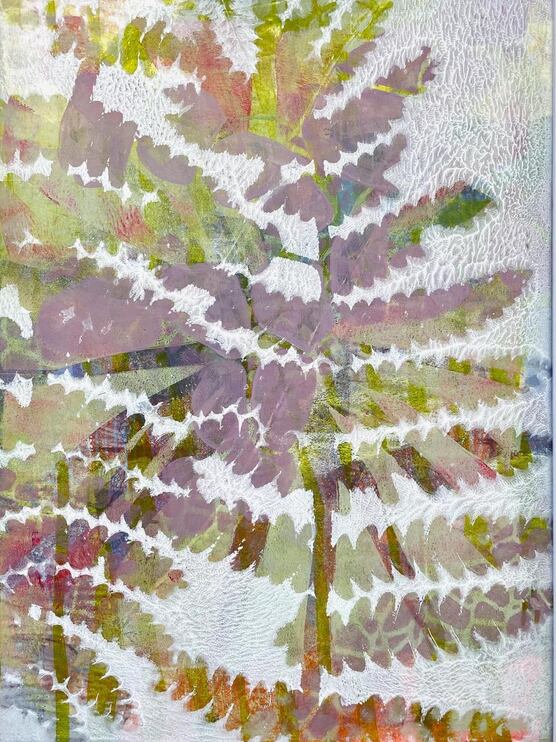

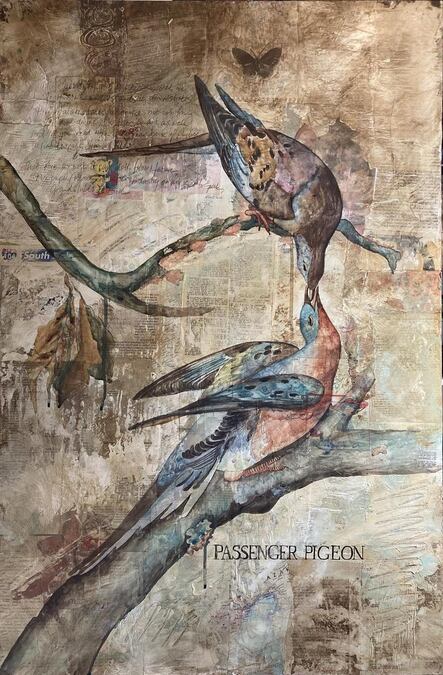

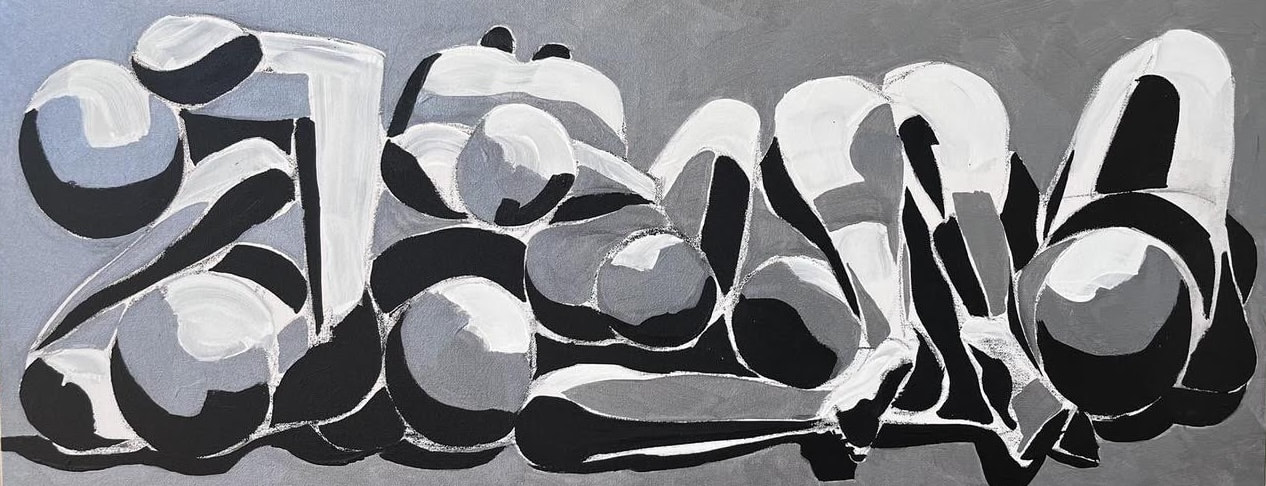

My Blue Moon I placed two drops of laudanum tincture under her tongue, the first dose of the day. Her cloudy eyes dipped slowly into the dark sunken circles of her moonface. Her hand slipped down to the side of the bed and rested at ease there. I observed the green and blue hues of her veins under her paper-thin skin, the way I do each and every day. The clear plastic tube jutting out of her fragile wrists irritated me, though I could never pinpoint why. The white lace curtains fluttered gently as the crisp Nordic air calmly settled into the room. I got lost in thought, just for a moment, of how much I missed my long locks getting tangled in the wind. It was then I caught a glimpse of how things used to be. How I used to pull on her wildly thick mane yet she always remained poised as she offered her loving arms to me. “Yes darling, I am here.” she’d say. A familiar tune awoke me from my reverie. Just outside the window, a cardinal perched on the bare weeping willow tree singing his morning melodies. I felt my glazed eyes blink, then blink again in awe of how truly red his red feathers appeared before me. I fluttered my lips and let my breath dissipate, turning my gaze towards her once more. Her chest rose up and down beneath the sheets gallantly, her fingers shifted now and then. Priyanka Patel Priya currently resides in Queens, New York where she was born and raised. The first book she ever owned was a Merriam-Webster dictionary gifted by her father. Since then, she has been intrigued by the power of words and illustrations. She enjoys writing poetry and prose inspired by nature, impromptu travel escapades, and seemingly ordinary days of life. She shares her writing with Woodside Writers group, a literary forum. Olmec Head, by Anon. (Mexico) c. 900-400 BCE Here is an Olmec head. I had been turning the pages of 10,000 Years of Art, examining the primitives – Cycladic or Neolithic figures, petroglyphs and drinking cups – and stumbled onto this raw lump of basalt. And there is a gloss beside each object, but what stayed my hand is what the sculptor made; A face to carve an empire with, a man might say, where ridge and furrow settle over cheek and jaw and stylized eyebrow, cut into the rock to make a ruler out of it, as if some god had called the stone to life. The mouth is slightly open, to breathe or command; the sightless eyes are fixed on nothing seen by tourists or museumgoers. Note the way the ideal penetrates the real in every feature. Those who ask for art will find it here, before the Aztecs came. To meet the man thus blazed into the rock – to know that face – I could. But I could not expect to see the force that makes of it a thing transformed by power and by light. John Claiborne Isbell John Claiborne Isbell is a writer and now-retired professor currently living in Paris with his wife Margarita. Their son Aibek lives in California. John grew up in the United States and Europe: Italy, France, Great Britain, Germany. His first book of poetry was Allegro (2018); he also publishes literary criticism, for instance An Outline of Romanticism in the West (2022) and Destins de femmes: Thirty French Writers, 1750-1850 (2023), both available free online. John spent thirty-five years playing Ultimate Frisbee, representing France in the European Championships in 1991, and finds it difficult not to dive for catches any more. It Wasn’t Bliss Too young for regrets, I had no clue what a chambered nautilus was, still our teacher walked us through the spiral rooms of that poem. First time I saw an O’Keeffe I was old enough to know, but—inexperienced and naïve-- I thought that flower was just a flower. I’ve scribbled my life with notes and reminders to the point where even I can’t decipher what I’ve written. What should I make of that? I have lived long enough now to appreciate the unwinding of a shell, the way a brush touches a canvas, how words can cultivate a field of rue. Matthew Murrey Matthew Murrey is the author of the poetry collection Bulletproof (Jacar Press, 2019). Recent poems can be found in The Dodge, Bear Review, HAD, and elsewhere. He was a public school librarian for 21 years, and lives in Urbana, IL with his partner. His website is at https://www.matthewmurrey.net/ . He can be found on Twitter, Instagram and Bluesky under the handle @mytwords. The Muse Brings Me a Horse after Earth Healer, by Carol Grigg (USA) contemporary The painting captures a woman riding a horse of lavender and sandstone colors disappearing into each other the way trees melt into fog. A veil hides her face, shawl falling like water across the girth of her steady gelding. His hind leg is raised, his thin muzzle searches out the wind. They cannot begin until a missing landscape appears on the canvas. A veil hides her fear of wanting what isn’t there. Perhaps she is a poet, waiting for a muse; the horse is her pen, poised, waiting for direction. They wait that way until she decides what is next. Let’s say the woman and the horse are one—then so are the poet and the pen. She has only to tear aside her veil and the way will appear. But the artist has given her no hands. If the horse runs very fast, perhaps the wind will solve her predicament—either way, she will arrive—or not while the ride keeps secrets of its own. Jackie Langetieg This poem was first published in Cup of Poems in 2003. Jackie Langetieg has published poems in literary magazines: Verse Wisconsin, The Ekphrastic Review, Bramble, Blue Heron Review. She’s won awards, such as WWA’s Jade Ring contest, Bards Chair, and Wisconsin Academy Poem of the Year. She is a regular contributor to the Wisconsin Poets’ Calendar. She has written five books of poems, most recently, Letter to My Daughter. and a memoir, Filling the Cracks with Gold. Editor's and Author's note: These poems, and the artworks they were inspired by, are from Poetry Convergence 2023. Poetry Convergence is an annual event in Massachusetts at Western Avenue’s Loading Dock Gallery. Poets write in response to a gallery show of new work curated at the gallery. The event is curated by poet, Stephan Anstey and artist Nan Hockenbury. ** Fern October, a year ago, we walked the woods at Great Brook Farm. Light through the turning maples overhead reminded us of stained glass. You were the one to first notice the ferns down at our feet, trailside, translucent the way they’d gone pale, so delicate, become the colour of antique lace. Fronds, not leaves, you said, nothing to fall, no flower to follow the steps of the sun or anthropomorphize Death or Desire. You told me they’d green again next spring, You, the one assuring me, though there was winter ahead, a hard winter. Passenger Pigeons The Inferno, Canto XI, Virgil tells Dante he should read his physics book carefully, persistently —get past the first few pages and you’ll notice how art —real work—follows nature. I’ve been reading a book about quantum theory, am nearly finished with the thing and I have to admit I haven’t yet a clue about what’s going on. I do gather they are trying to understand light. Remote causality has me stumped though. And math’s still the language—for all its elegance—that can leave me dazed with its stark, dizzying obscurity. I am not a man of science. To me one theory’s as good as the next. Hear the word ‘PROOF’ and I think of those flawed versions of school picture I brought home as a kid—hair out of place—something wrong in the facial expression. We’d keep them in a drawer, though I sensed we weren’t supposed to Emptying out the old house, I found them, evidence of a parallel universe. Indignation Just as there’s a difference between innocence and ignorance what’s left unspoken isn’t peace. Place names never said, not without an echo of pain, pang of conscience —Wounded Knee, Mai Lai, Abu Ghraib. Hard image comes to mind and even as bodies abstract, compose, they become only, simply beautiful shape and shadow, coloured in a light beyond seeing, light nevertheless known by inference, its disquiet history. It's the one’s we know we’ve harmed, whose voices disappear and leave this terrible silence. Beautiful Resilience for Sinead Ice formed on the flooded plain sometime in the night. What’s left of the storm is broken cloud-cover and sharp wind —gusts. Brittle grass gone gold-brown with autumn weeks ago makes small crisp noise with each of my footsteps. I’m thinking of that singer’s voice the way it could turn within a breath —rage—sorrow—aching tenderness. My thoughts can’t find rhythm—they’re shoes not made for this terrain—and, still, I am walking this morning —cold air in my throat. That sapling some distance off, one note, her song. Trying to Speak, You’ll Never Know No Matter How Loud The first thing I ever said to you, I said without thinking; your answer, too, was something about a mistake. We’ve remembered the day differently. You always say it was some time in May and I recall there being winter coats and later saying your name to the black water below the North Washington Street Bridge, —it was late, alone, the night starless as a car drove past, rattled the steel grating at my feet, I looked down to see how its grid sifted the stir of reflected urban light and ink black river flow. Against the cold, against the noise —your name —a theory, a song, a prayer. —I’m not sure, now, if I even said it aloud. Tom Driscoll Tom Driscoll is a poet, columnist, and essayist who lives and works in Lowell, Massachusetts with his wife, artist Denise Driscoll. The Champion of Doubt, published summer 2023 from Finishing Line Press. Driscoll’s poetry has appeared in Oddball Magazine, Carcosa Review, Scapegoat, Paterson Literary Review, and The Worcester Review. Two, from Meret Oppenheim Objet It’s one thing to kill an animal in the wild for its meat, a warm covering, and other essentials; another to scissor an ocelot’s pelt into small pieces and adhere them to a gold bracelet. Twenty-three-year-old Meret Oppenheim did just this, all in the name of fun and high fashion. In 1936, she sat with Picasso and his new lover Dora in a small French coffeehouse called the Café de Flore. While taking tea, they admired the unusual bracelet on her wrist. Meret’s tea began to cool. She signaled to a waiter, asking him for "un peu plus de fourrure" to warm up her cup. Picasso casually suggested that she might surround anything with fur. Meret laughed, “Even this plate and this cup here!” A teacup, saucer, and spoon lined with the fur of a Chinese gazelle. No doubt, the easiest to cover was the saucer. A flat surface, the fur trimmed to overlap the edges by half an inch. The exterior might have been next, wrapped with a single strip of white, perhaps from the animal’s belly, combed in one direction to train the nap. Lining the cavity would require some scissoring to avoid bunching or overlap. The spoon too must have been a particular challenge, especially its narrow stem. Then the ear with its tight curve, where we can’t help but notice some balding—the bright yellow china blaring through. “Beauty will be convulsive or will not be at all,” said Andre Breton, author of the Surrealist Manifesto. He was smitten and arranged Meret’s very first showing in Paris at the Charles Ratton Gallery. The cup then found its way to New York where it was an overnight sensation. This single artwork took Oppenheim from a meager living designing jewelry to the titular First Lady of MOMA and showings around the world. Positioned on a small white platform in a glass case, Objet is often the most popular exhibit in the museum. As visitors approach, their reactions to the cup are quick to emerge, especially at the recognition of what rests in the bowl of the spoon. It’s not honey or cream or sugar, but hair. One observer feels like choking, supposing a whisker is stuck to the roof of her mouth. Another imagines swallowing ticks or lice or particles of skin and quietly slumps to the floor. A third jokingly asks the guard could he lift the cover; all she wants to do is fondle it. There are winces and abrupt turnabouts and guffaws and shouts of delight. Oh, the daring, the horror, the brilliance, the oppositional defiance! But hold on, early artistic achievements can be problematic. Although she had created many other works of art—sculpture, costume, paintings, collage, even theater, many people assumed all she did was fur. And when the buyers at MOMA approached her with an offer to buy the cup, she haltingly asked for a thousand francs. It was their very first acquisition of an artwork by a woman. They gave her fifty dollars. Even back then, fifty dollars didn’t last very long. For financial and emotional relief Meret was forced to move back to Basel and work in art conservation. She no longer fit in with the traditional, introverted, and rule-bound Swiss and was miserable. Follow the gazelle running along a hot savannah in Africa, recall the gunshot and the pelt wrenched from its body—its discarded corpse smoking in a pile with three or four other lifeless gazelles. Follow the long life of the Objet Meret once referred to as “my prison.” Success did not sit well. She told several people the cup was meant as jest, a curiosity, certainly not the iconic emblem of an artistic movement. She felt pressured to create an equally stunning second act and, overwhelmed, withdrew from her circle of Surrealist friends. She sank into a two-decade depression, and couldn’t finish, or destroyed the work she created. On her 36th birthday, she described a dream in which a skeleton held up an hourglass, its contents falling fast. My life is half over, she thought. The vision proved amazingly prophetic, as she died in 1985 at the age of 72.

Votive Picture (Strangling Angel) Meret was obsessed with shoes. In photographs of her brown leather boots, the tops gape like open mouths. Her laces slump pathetically around her ankles. In another snapshot, she nestled shoes—her own white high heels—upside-down on a silver platter. They are trussed up with string and paper frills like a roasted turkey. She called the image Ma gouvernante, or My Nurse. In this painting, she introduces an angel wearing wings, or are they not wings but a set of snow-covered mountains, tiny pine trees perched atop them? We will never know. If she is an angel, she’s a very bad angel indeed, holding a naked baby, its head drooping, its throat cut. A pink gush of blood falls to the earth, staining her white skirt, and defacing its pattern of gold stars. They appear to be drifting away, and no wonder. She is a terrible angel, a horrific mother. Perhaps she has slit the throat herself with her long fingers and incredibly sharp nails. Her blouse is covered with navy blue moons, and they too suffer a splash or three of pink. She’s kneeling on the ground which is littered with the corpses of other women wearing high heels, one pair of blue, and one of pink, the latter stained with blood. What have they done to deserve this? Her body is grotesquely angular, especially the shoulder, chin, and lips. This is not a mouth to kiss, or be kissed by, not a shoulder to cry upon, neither a crook of the elbow to cradle a baby. Alas, on closer inspection, there are indeed feathers, sketched rather randomly on the wings. Should God have granted her this honour, these dusty white appendages. What gall to imply the Bad Mother was some sort of heavenly host, blithely sacrificing the child in a selfish attempt to gain fame and forgiveness? Sarah Gorham Sarah Gorham’s forthcoming essay collection is Funeral Playlist from Etruscan Press. She is the author of Alpine Apprentice, shortlisted for the PEN/Diamonstein Award, and Study in Perfect, selected by Bernard Cooper for the AWP Award (both University of Georgia Press books.) Other books include Bad Daughter, The Cure, The Tension Zone, and Don’t Go Back to Sleep. Grants and fellowships include the National Endowment for the Arts, three state arts councils, and the Kentucky Foundation for Women. Media coverage included Salon, NPR, Utne Reader, Slate, and Real Simple. She co-founded Sarabande Books, inaugural winner of the AWP Small Press Publisher Award. The 3D House of Pierogi This can’t be real, right? People driving all night for potatoes in dough across the Pierogi pocket-- New York, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana, Chicago, Detroit, and parts of New England, just to get to Pittsburgh. Put that in your pipe and smoke it, Irving Berlin. AAA TripTik® official, like we even need that with sauerkraut in the air here. 4 Pierogi in a Rainstorm The Princess and the Pierogi Taylor Swift —the Pierogi Tour Pierogi Races at Pirate games. You gotta believe. St Hyacinth and his place over on Craft Avenue —-this guy. Legend. Here’s the skinny:

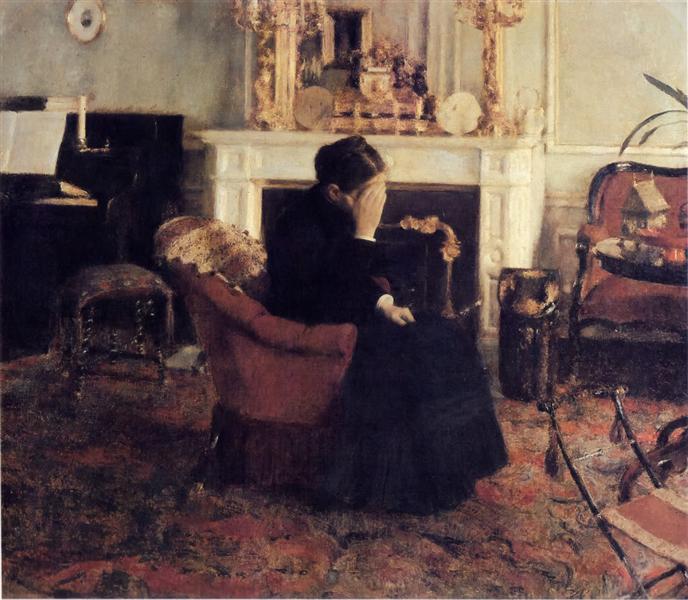

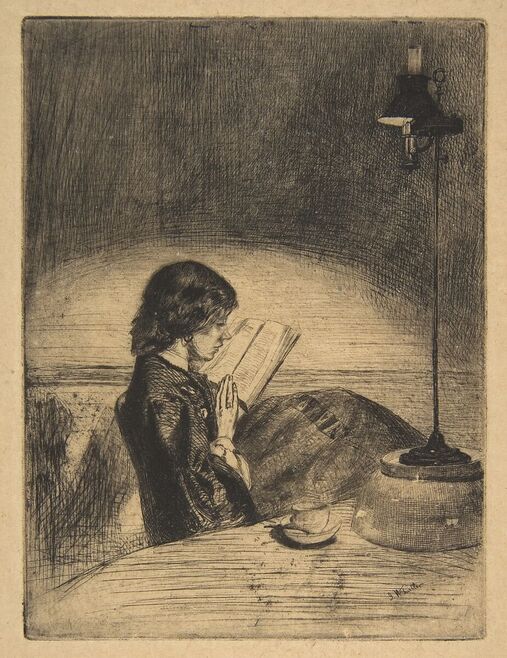

A real flower of a man and flour. Who knew? “St. Hyacinth and his pierogi!" the hopeless cry, and there he is, just like Batman, except more fragrant. Because he is named after a flower named by a sun god even inside all the gloom on earth. Real superhero stuff, this one. Remember those announcements from years ago of sales out of the rectory kitchen there on Craft, long lines in the cold down the surrounding streets in the pre-holiday hours, making jokes with Dennis the Menace dads wearing fogged-upped glasses and deerstalking caps with one earflap up and the other down as you stand there, high-hair-wearing teens in Catholic school uniforms--with cold knees above knee socks or neckties discarded entirely or now around heads like bandanas--behind you cracking gum and shifting around as they do when forced to wait? You keep watching your breath blow away and the grey of the sky deepening over above Panther Hollow, sure it’s bound to snow soon, till finally you’re inside that square of yellow light—the very kitchen door itself—handing over your crumpled pre-paid order slip and receiving still warm bundles placed from their babushka crowned maker’s hands into your own. This is where the expression ‘wreathed in smiles” was made, you know, from the prickling delight of festive, unleavened dough wrapped around hot potatoes, good for warming pockets and bellies and drawing you close and even closer through the sheer heaven of hot onions and butter seeping out around the edges of the foil in your frozen hands. The wafer and the Virgin And the Pierogi. Talk about your Holy Trinity, the Trifecta of Help. Say an Ave for St. Hyacinth and his crew, his crib long closed and now a nightclub on occasion, all the Babas gone to a new combined parish called All Saints or All the Beloved or All that Jazz by the Diocese desperate to retain its flock having forgotten by now the indulgences paid so willingly and so often for the sake of hot potato filling and neighbours standing together on cold Pittsburgh streets. Kate Bowers Kate Bowers (she/her) is a a Pittsburgh based writer who has been published in Sheila-Na-Gig, Rue Scribe, and The Ekphrastic Review. Her work appears also in the anthology Pandemic Evolution: Poets Respond to the Art of Matthew Wolfe, by Hayley Haugen (Editor) and Matthew Wolfe (Contributor) and will appear also in the forthcoming anthology The Gulf Tower Forecasts Rain to be published in the spring of 2024 by Pittsburgh’s City of Asylum. Kate is an alum of Tupelo Press’s 30/30 Project and serves as a volunteer social media team member for The Ekphrastic Review. Notes from a Small Room Why do I love singing Schumann? Because he can make me feel all the many ways that the woman in Fernand Knoppff's 1883 painting Listening to Schumann seems to feel: awed, musing, and perhaps even pained. She's wearing black—is it a sign of mourning? I saw it in Brussels' Fine Arts Museum and though I had never heard of the painter, the moodiness of his work cast a long-lasting spell. So when looking for repertoire to study with my voice teacher, I found a Schumann art song--a lied--that wouldn't just fit my bass/baritone voice but could match all of those feelings I saw in the painting and perhaps more, some even mysterious. And I sensed that singing the song wouldn't be enough, I would have to write about it somehow. When I started voice lessons well before the pandemic, I didn’t understand that being a writer would be a valuable resource in my weekly lessons. Learning a song was much more than the notes, the phrasing, making sure I had enough breath for each line--and everything else I was discovering about voice. The words themselves really mattered. The words, and what I made of them. As one teacher advised: “Think of the story you’re telling with each song.” And I had no idea that my teachers would offer delicious metaphors to help me make progress. The latest: I am like a guitar, and the way the sound of strings resonates inside the guitar and then issues forth is a model to keep in my head. That's where I should be feeling the resonance. I've never played a stringed instrument, but as a lover of metaphors, this new one felt illuminating. Now, while I loved the musicality of Schumann's "Du Bist wie eine Blume," I confess that a significant attraction was its length: just a page long. That made me feel less anxious about studying it, especially since I knew that speaking German as I did was very different from singing it. The German words of the Schumann lied were not complicated in of themselves; they’re taken from a poem by Heinrich Heine, “Du bist wie eine Blume (You are like a flower)": Du bist wie eine Blume, So hold und schön und rein; Ich schau’ dich an, und Wehmuth Schleicht mir in’s Herz hinein. Mir ist, als ob ich die Hände Auf’s Haupt dir legen sollt’, Betend, daß Gott dich erhalte So rein und schön und hold. The poem addresses someone beloved, comparing her to a flower that is beautiful, pure, and lovely. When I look at you, the speaker says, melancholy creeps into my heart. He feels as if he should lay his hands on the beloved’s head and pray to God that He will always keep the beloved pure and so on. I had heard many versions of the song online and thought it was beautiful, but when I actually read the words, some of which were slightly archaic, I was a bit put off. It all seemed kind of kitschy. But the more I considered the poem apart from the music, the more engaged I became. That gesture of putting hands on someone’s head is like a benediction, and that’s amplified by praying to God that the beloved never change. And then it hit me: this is an elegy. It’s not just about the beautiful love object, it’s a mournful recognition that praying to God, laying on of hands won’t stop time. After all, flowers bloom and die: beauty is transitory. That explained the melancholy creeping (or stealing) into the speaker’s heart. The opening of the piano accompaniment confirmed that for me. It briefly sounds like a march or a drum beat before the singer joins the piano—and for me that evoked the March of Time. The poem has been set to music by a number of composers, but the Schumann version was the most melodic. As a writer, I’m fond of research so I read a lot about Schumann himself and discovered that he may have been in love with a man before his marriage. Does it matter? In a way, yes, because it opened up the song even more for me as a gay man, made the yearning to stop time stronger. While I had trouble at first connecting with the lied despite how taken I was by the music, once I reached an understanding of the words, the emotion followed. I’ve heard it sung many ways, but what's helped me sing it my way was reading it as a writer, first of all, and not just entering the song, but letting it enter me. And when I sing this lied, I imagine myself in that somber room, listening along with her. I see the music of this song on the piano behind her, and wonder if she'd like to hear me sing it for her. Or just have me take her other hand. Lev Raphael Lev Raphael is a first-generation American whose refugee parents spoke many languages, loved music and art, and took him to MOMA, the Guggenheim, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art when he was very young. Those visits inspired him to become a writer. His work has appeared in Salon, The Washington Post, Tablet, Forward, The Detroit Free Press, Jerusalem Report, The Smart Set, the Gay & Lesbian Review and dozens of other publications. He lives in Michigan with his husband and two West Highland White Terriers. On Plato and Lamplight The lamp at her desk is more for comfort than necessity – she has always been afraid of the dark, and anyway the book in her hands is one she could recite, she is sure, word for word. An ancient philosophical dialogue about time and the sun, about the nature of reality. The nature of society. The physics of light and space – how one's placement on the horizon changes what can be seen and what will be perceived. Books have always been easier than people, she thinks. The people in books easier than the people outside of them. Their thoughts and feelings clearer, sharper. Their ideals more real than the time it takes to absorb them. Beyond the safety of her desk and its protective lamp, the world warps into a primordial black hole – a carnivorous echo chamber, feeding off of its own distortions. Unwritten rules. Unreadable expressions. Flashing cameras and shiny faces, their fixation on perfection without form. Even now, Plato’s shadow puppets flutter about her vision, blurring the edges – chattering and buzzing and eclipsing the light. She used to think it would get easier, as time passed. Her spotlight brain would grow into spotlight eyes, able to read books and words and people with effortless ease, even deep within the darkness of the cave. She wouldn’t need a lamp to calm her rabbit-quick heart. She wouldn’t need a hardback spine, or an exoskeleton surrounding her oversensitive insides. She wouldn’t need to be afraid of the dark. She wonders what the ancient philosophers would think about redshift, and the shape of gravity. The way the world bends beneath the weight of light. She wonders if perhaps Plato was afraid of the dark too. Kimberly Hall Kimberly Hall (she/her) is a queer and neurodivergent writer based in Southeast Texas, with a master's degree in behavioural science. Her work has appeared in several print anthologies, including Chaos Dive Reunion (2023) from Mutabilis Press, as well as in online publications such as Sappho's Torque, Equinox, and The Ekphrastic Review. She is currently working on her first collection of poetry. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|