|

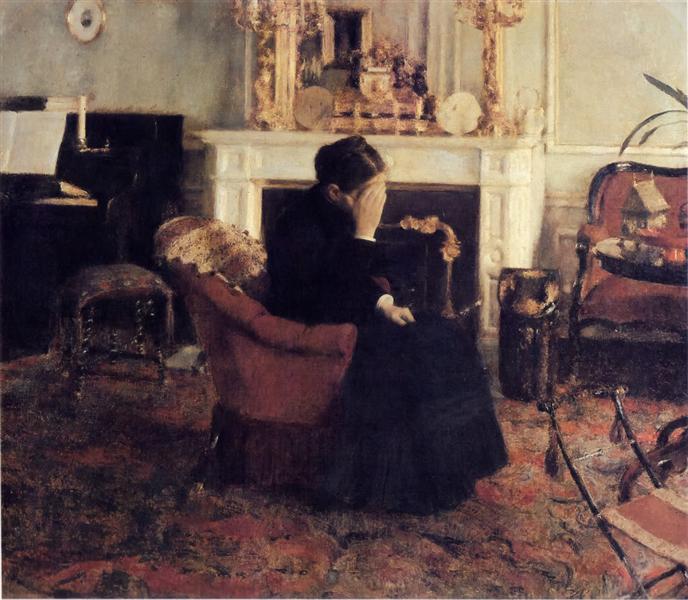

Notes from a Small Room Why do I love singing Schumann? Because he can make me feel all the many ways that the woman in Fernand Knoppff's 1883 painting Listening to Schumann seems to feel: awed, musing, and perhaps even pained. She's wearing black—is it a sign of mourning? I saw it in Brussels' Fine Arts Museum and though I had never heard of the painter, the moodiness of his work cast a long-lasting spell. So when looking for repertoire to study with my voice teacher, I found a Schumann art song--a lied--that wouldn't just fit my bass/baritone voice but could match all of those feelings I saw in the painting and perhaps more, some even mysterious. And I sensed that singing the song wouldn't be enough, I would have to write about it somehow. When I started voice lessons well before the pandemic, I didn’t understand that being a writer would be a valuable resource in my weekly lessons. Learning a song was much more than the notes, the phrasing, making sure I had enough breath for each line--and everything else I was discovering about voice. The words themselves really mattered. The words, and what I made of them. As one teacher advised: “Think of the story you’re telling with each song.” And I had no idea that my teachers would offer delicious metaphors to help me make progress. The latest: I am like a guitar, and the way the sound of strings resonates inside the guitar and then issues forth is a model to keep in my head. That's where I should be feeling the resonance. I've never played a stringed instrument, but as a lover of metaphors, this new one felt illuminating. Now, while I loved the musicality of Schumann's "Du Bist wie eine Blume," I confess that a significant attraction was its length: just a page long. That made me feel less anxious about studying it, especially since I knew that speaking German as I did was very different from singing it. The German words of the Schumann lied were not complicated in of themselves; they’re taken from a poem by Heinrich Heine, “Du bist wie eine Blume (You are like a flower)": Du bist wie eine Blume, So hold und schön und rein; Ich schau’ dich an, und Wehmuth Schleicht mir in’s Herz hinein. Mir ist, als ob ich die Hände Auf’s Haupt dir legen sollt’, Betend, daß Gott dich erhalte So rein und schön und hold. The poem addresses someone beloved, comparing her to a flower that is beautiful, pure, and lovely. When I look at you, the speaker says, melancholy creeps into my heart. He feels as if he should lay his hands on the beloved’s head and pray to God that He will always keep the beloved pure and so on. I had heard many versions of the song online and thought it was beautiful, but when I actually read the words, some of which were slightly archaic, I was a bit put off. It all seemed kind of kitschy. But the more I considered the poem apart from the music, the more engaged I became. That gesture of putting hands on someone’s head is like a benediction, and that’s amplified by praying to God that the beloved never change. And then it hit me: this is an elegy. It’s not just about the beautiful love object, it’s a mournful recognition that praying to God, laying on of hands won’t stop time. After all, flowers bloom and die: beauty is transitory. That explained the melancholy creeping (or stealing) into the speaker’s heart. The opening of the piano accompaniment confirmed that for me. It briefly sounds like a march or a drum beat before the singer joins the piano—and for me that evoked the March of Time. The poem has been set to music by a number of composers, but the Schumann version was the most melodic. As a writer, I’m fond of research so I read a lot about Schumann himself and discovered that he may have been in love with a man before his marriage. Does it matter? In a way, yes, because it opened up the song even more for me as a gay man, made the yearning to stop time stronger. While I had trouble at first connecting with the lied despite how taken I was by the music, once I reached an understanding of the words, the emotion followed. I’ve heard it sung many ways, but what's helped me sing it my way was reading it as a writer, first of all, and not just entering the song, but letting it enter me. And when I sing this lied, I imagine myself in that somber room, listening along with her. I see the music of this song on the piano behind her, and wonder if she'd like to hear me sing it for her. Or just have me take her other hand. Lev Raphael Lev Raphael is a first-generation American whose refugee parents spoke many languages, loved music and art, and took him to MOMA, the Guggenheim, and The Metropolitan Museum of Art when he was very young. Those visits inspired him to become a writer. His work has appeared in Salon, The Washington Post, Tablet, Forward, The Detroit Free Press, Jerusalem Report, The Smart Set, the Gay & Lesbian Review and dozens of other publications. He lives in Michigan with his husband and two West Highland White Terriers.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|