|

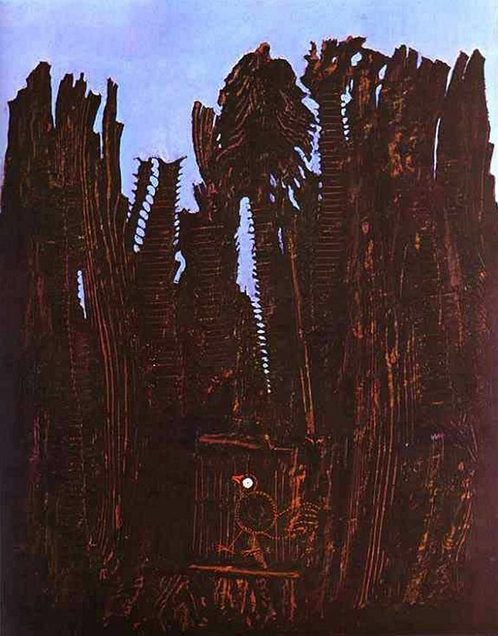

Forest and Dove

You remind me of something Max Ernst would come up with – must be the way you hide among the razor-like trees inside your head. And if I were to step on that path, like some child in an old fairy-tale, I would not be afraid. Even under a blue sky, this forest is as dark as the belly of a mechanical beast. But I would not turn back. And I would not stray. You’ve kept her alive in here somewhere. I know I can find her. I’ve heard her sing. Anca Rotar Anca Rotar is a Romanian-born writer of poetry and fiction. She was driven to writing by her love of stories and verse, as well as by an ever-increasing fascination with mysteries and the unknown. Her biggest complaint is that there are too many interesting things in the world and hardly enough time to discover them all. http://ancaspoemsandstories.wordpress.com

0 Comments

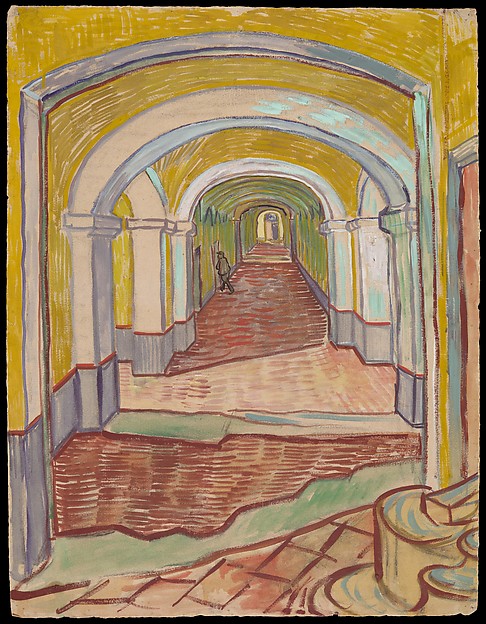

Yellow

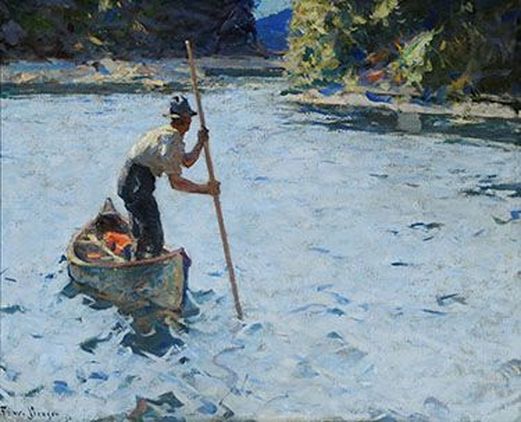

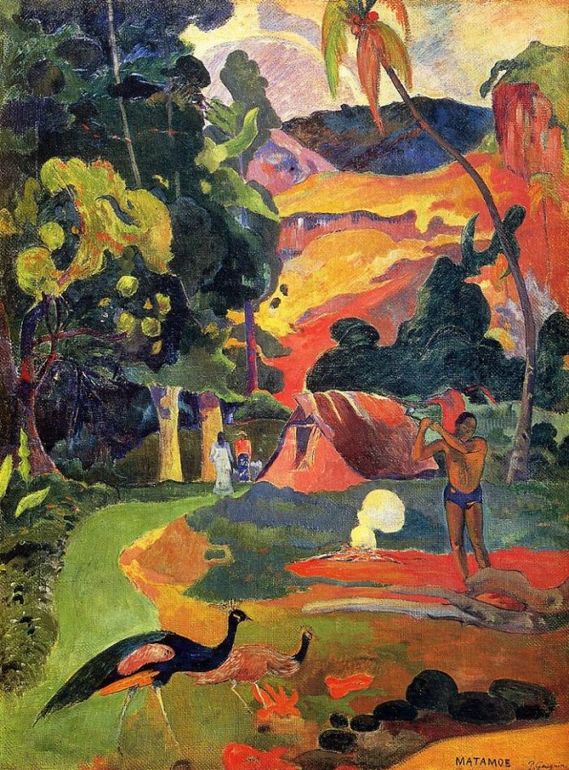

Colour of sun-soaked sandstone, glaring nightmare of high arches, labyrinthine passages back and forth, to and fro, no escape. Colour of confusion, tip-tap of following footfall ebb and flow, impossible to pin down in the echo. Colour of anxiety, cold sweat of fear, exposed by bare corridors, no quiet corner to cower in. Colour of cowardice; not a choice here, no holes to hide in, tremor of terror, even a hero would run. Ann Gibson Ann Gibson spent her childhood in Dublin and now lives in North Yorkshire. She has always been an avid reader and has, more recently, learned to enjoy writing and playing with words. She combined these interests when she completed a part-time MA in Literature Studies at St. John’s University in York. She has published poetry in Acumen, Prole, Orbis and Ariadne’s Thread, as well as Leaf, Blinking Eye, Biscuit, Chuffed Buff Books, and other anthologies. More recently her poetry has appeared online in Lighten Up Online, Snakeskin, Pulsar and Ofi Press Magazine. Salome with the Head of St. John the Baptist I, Michelangelo Merisi -- known in my time and yours as Caravaggio painted this scummy episode: a pouty nymphet who made stepdad Herod come in his pants, now refusing to look at the head-on-a-platter, and besides it was all my stupid mother’s fault. You might think instead this was -- as you people say -- about ‘speaking truth to power’, and look where it gets you. No, for me, the really compelling character is the executioner: jug-eared, busted nose, the sort of thug you’d hire off the docks to do some dirty work and do it right. A kind of in-your-face self-portrait. Norbert Hirschhorn Norbert Hirschhorn is a public health physician, commended by President Bill Clinton as an “American Health Hero.” He lives in London and formerly in Lebanon. He has published four collections: A Cracked River (Slow Dancer Press, London, 1999), Mourning in the Presence of a Corpse (Dar al-Jadeed, Beirut, 2008), Monastery of the Moon (Dar al-Jadeed, Beirut, 2012), and To Sing Away the Darkest Days, Poems Re-imagined from Yiddish Folksongs (Holland Park Press, London, 2013). His poems have appeared in numerous US/UK publications, several as prize-winning. See his website,www.bertzpoet.com. Following the Light High noon, the water bright as the idea the man had thirty minutes ago when he set sail in his canoe, alone, long wooden pole in hand, flinging his orange vest onto the seat, seeking nothing but a certain slant of light, not even a single fish, in the middle of summer in 1920 & the Grand River: Behind him is another life, maybe a wife, maybe children, wondering where he’s off to now, prone to wander as he often is, not far from home, never in an untrue manner, but still, disappearing on days like this once the urgent work is finished, glint in his eye giving him away to the old dog, the only one who catches him as he grabs his hat & heads out back. The hound knows this is no hunting trip into the woods, no trek up the mountainside, knows to stay put & return to his dreams of raccoon chases & bones buried within reach. What the man does in the canoe is a balancing act: As the blue-tailed damselflies flit & flash, he hunches, slides the pole to the mud below then pushes down, pushes forward, pursuing Monet’s palette of yellow, green, orange, purple, blue in every hue, all rippling in the pines on the shoreline & farther still, in the current yet to come, something swift, something slow. Julie L. Moore This poem was previously published in ASCENT. Julie L. Moore is the author of three books of poetry: Particular Scandals, Slipping Out of Bloom, and Election Day. Her poetry has appeared or is forthcoming in Alaska Quarterly Review, Image, New Ohio Review, Nimrod, Poetry Daily, Prairie Schooner, The Southern Review, and Verse Daily. You can learn more about her work at julielmoore.com. John William Waterhouse’s Saint Eulalia

With all its keen attention to detail, With its foreshortened shot of a stripped-down girl Sprawled out on a slab of stone as snowflakes fall, It seems designed to disturb, and so it does. We see three doves, but whether they have flown Up from her mouth, as poet Prudentius penned, This strict and heartless picture does not affirm. We are left on our own for miracles, With little help from the artist himself or from The stolid Roman soldier who stands to one side, Perhaps to guard the chilling corpse from those Who might be tempted to tamper with it more, As if to scorch her body “with fierce flame,” As Bede’s hymn has it, were not enough. Still, the pubescent torso lies pristine. Victorian men, our scholars venture, found the sight Erotic. (The man who bought it had it hung In his billiards room, hardly a fair fate for A maid courageous enough to censure the state For hating, hurting followers of Christ.) William Ruleman William Ruleman is Professor of English at Tennessee Wesleyan University. His newest books include the poetry collections From Rage to Hope (White Violet Press, 2016), Salzkammergut Poems, and Munich Poems (the latter two from Cedar Springs Books, 2016), as well as his translations of Hermann Hesse’s early poems (Cedar Springs Books, 2017) and Stefan Zweig’s unfinished novel Clarissa (Ariadne Press, 2017). Blues, now,

even in the brain, in the rests broken with the pain of not knowing your own notes, your own voice. It’s a cruel stranger that encores the dementia dirge and tricks even the soul- ful into forgetting the name- sake. O, Fats, O, Etta-- Ain’t That A Shame and Fool That I Am got switched at the synapse and all that jumbles the soul clogged up and stopped singing the self. Still, mellow Fats, when those cats sang you gone with Katrina, you knew to insist that behind those silent lips, you’re still blues-ing and twisting. And, Sassy Etta, when last winter caught you rolling death, tell me you remembered, somewhere in your blues-infused brain to cat-call all of us, then belt out At Last again. Marjorie Maddox This poem was previously published in New York Dreaming. Sage Graduate Fellow of Cornell University (MFA) and Professor of English and Creative Writing at Lock Haven University, Marjorie Maddox has published eleven collections of poetry-including True, False, None of the Above (Poiema Poetry Series and Illumination Book Award medalist); Local News from Someplace Else; Wives' Tales; Transplant, Transport, Transubstantiation (Yellowglen Prize); andPerpendicular As I (Sandstone Book Award)-the short story collection What She Was Saying(Fomite Press), and over 500 stories, essays, and poems in journals and anthologies. Co-editor ofCommon Wealth: Contemporary Poets on Pennsylvania (Penn State Press), she also has published four children's books: A Crossing of Zebras: Animal Packs in Poetry, Rules of the Game: Baseball Poems ; A Man Named Branch: The True Story of Baseball's Great Experiment (middle grade biography); and Inside Out: Poems on Writing and Reading Poems + Insider Exercises. For more information, please see www.marjoriemaddox.com Rinaldo Enchanted by Armida There is nothing wrong with this picture. The heavens open as only they can in myth, and through that marvelous gap, a chariot sweeps down: a woman reins in the cloud-wings of her stallions. She wafts you to her bosom with a flick of her finger. You pinch yourself, but then, you lie back and close your eyes, as she descends, the clouds billowing about her body the wisp and flex of their gossamer power. Everywhere, pieces of sky, little amoretti, appear; you drop your sword, your shield, . . . the helmet which held your imagination so tightly to your head; all the enchantments of war fall before her as if this could keep you from your destiny. Tim Mayo Tim Mayo is the author of The Kingdom of Possibilities (Mayapple Press, 2009) and Thesaurus of Separation (Phoenicia Publishing, 2016), which was a finalist for the 2017 Montaigne Medal and a 2017 poetry category finalist for the Eric Hoffer Book Award. Publications include Barrow Street, Narrative Magazine, Poetry International, Poet Lore, River Styx, Salamander, San Pedro River Review, Tar River Poetry, Web Del Sol Review of Books, Verse Daily, and The Writer’s Almanac. He is a six time Pushcart Prize Nominee, a finalist for Paumanok Award, and the recipient of two Vermont Writers Fellowships from the Vermont Studio Center. He lives in Brattleboro, VT, where he was a founding member of the Brattleboro Literary Festival. Right and Left Bang -- beyond the oil painting’s frame resounds the double-barreled shotgun’s blast. Through wisps of smoke and fog we see the flame. Two ducks with golden eyes in the overcast sky diverge above a darkened white-capped wave. One, wings spread, is frozen in its flight; the other dives into the sea to save its life. We too are in the hunter’s sight, helplessly aligned with the fired shot, confronted with our own mortality while the boat rises on a frothing crest. Does the duck that dives escape the onslaught? Perhaps both birds are lucky, breaking free, or does a bullet split each beating breast? Gregory E. Lucas Gregory Lucas (Hilton Head Island, SC) writes fiction and poetry. His short stories have appeared in The Horror Zine, Dark Dossier, Pif, Blueline, The New Press and in other magazines. His poems have appeared in Peeking Cat Poetry Magazine, Scarlet Leaf, The Lyric, Blueline, Literary Juice, Straight Forward Poetry, and in other magazines. Commute Who hasn’t thought it? You’re driving home through the gray part of town, in the gray part of day. Almost sleepdriving, following other cars in an ant trail up and down, up and down – the red lights barely bright enough to break your trance. What if – just once – you take off, turn onto the interstate. St. Louis, Chicago, Denver – commit to a direction and go! Alarie Tennille Alarie’s latest poetry book, Waking on the Moon, contains many poems first published by The Ekphrastic Review. Please visit her at alariepoet.com. You Cannot Imagine What is Before You It is a curious fact that when something lodges in your mind and will not go away you come across it everywhere. Take the colour red for example. One day I picked up a second hand paperback copy of Joseph Conrad’s first novel, Almayer’s Folly, somewhere, I forget where now. It was an Everyman edition that used Paul Gauguin’s painting Landscape with Peacocks as a cover illustration. Since becoming aware of his work many years ago his bold use of primary colours has been an abiding pleasure to look at, both his Pont-Aven school Breton pieces through to the later Tahiti ones. Reading the first few chapters of the novel I could see why this illustration had been chosen even although the novel is set in Borneo rather than Tahiti, and peacocks are never mentioned that I could see, unless they become symbolic of the ‘folly’ in the book’s title. The editor of this edition tells us that Conrad revised the novel for the collected edition of his novels and excised many phrases and images. Perhaps he was interested in the more sombre vicissitudes that aim for posterity. For example, Conrad took out a philosophical phrase spoken by Almayer: “You cannot imagine what is before you.” It carries a neat ambiguity. Does it mean what is physically before you, or what your future is to be? Luckily this edition of the book follows the text of the first edition and retains such gems. Where has red got to, you ask? Also excised in the early chapters of later editions are references to Almayer’s estranged Malay wife spitting out betel nut juice onto the earth floor of their dilapidated house and making red splash marks. The Sumatran servant has the same habit. Betel nut juice also stains the mouth, tongue and lips; the nut is chewed as a mild intoxicant. Around the feet of the peacocks in the Gauguin picture are splashes of red, perhaps they are exotic flowers, again they could be juice spat from someone’s mouth. This is impossible to judge. A yellow path winds up towards two female figures in the mid-distance that stand side by side beside a small native house. One figure is dressed in white, the other in red. The former could represent Almayer’s beloved daughter Nina and the latter the deranged wife and mother of the girl. The house has a reddish orange glow and a fire burns in the foreground with the same colour and a puff of white smoke. It is difficult also to judge what time of day is being depicted as off to the left is dark green jungle. In the top right hand corner is a weaving block of red and orange that could be sky at dawn or dusk. Much of the action in the novel takes place in the short dawns and dusks of the tropics. The final red in this short novel is: “a long strip of faded red silk with some Chinese letters on it.” This, in the closing pages of the novel has been hung up in Almayer’s house by Jim-Eng, an old Chinese friend and opium smoker, who moves in after Nina departs with her lover and mad mother. Almayer dies; we don’t learn the true cause just that he has been “delivered from the trammels of his earthly folly.” The last owner of this particular copy of the book had left two airline boarding passes tucked between the last page and back cover. They belonged to a Mrs Patricia Salvi, whose name is on them. Both flights were taken about six weeks between each. The first was a domestic flight in Portugal from Lisbon to Porto with Portugalia Airlines on 1st March. The second was an international flight with Philippine Airlines to who knows where and marked by a red immigration departure stamp; this journey taken on 24th April. I could see from the stamp that the flight was in the year 2000. I noticed, almost in passing, that the logos of both airlines contain the colour red. I assumed that this novel of Conrad’s was in-flight reading for the lady; an interesting choice, as the Philippines is geographically close to Borneo. And why take the same book on two separate flights? Conrad is never the lightest of reads, even in this his first novel that was directed at an audience attracted to ‘romance’ and life in far-off places. Perhaps she is a lecturer with a specialist interest in Conrad’s work. If so I would have expected underlining and margin comments in pencil. I guess there are many reasons why somebody should pick up a book and read it. Personally I had always found Conrad’s prose a little difficult, having to concentrate carefully with writing by a Polish born writer who found success writing in his third language. So, I finished the sad tale of Almayer, congratulating myself I had done so and making a mental note to try some of Conrad’s later work sometime. The book went on a bookshelf as I dislike letting books go even if they are never read again. That should have been the end of my association with Almayer’s Folly as it gathered dust on a shelf complete with Patricia Salvi’s two boarding passes between its covers. One day, a while later, I forget how long since reading the book, my doorbell rang. I went and opened the door. A woman stood just away from the doorstep. She seemed to lean back a little with her right knee and foreleg bent forward. She was clearly striking a pose. I guessed she was in her forties, dressed in a dark blue jacket and skirt business outfit with a white blouse, black shoulder bag and shoes. The most striking features in her ensemble were a red silk scarf tied loosely round her neck and bright red lipstick. Long dark hair, brown eyes and olive complexion completed her appearance. As I opened the door she broke into a broad smile like a stage curtain opening on a beautiful scene, for she was indeed beautiful. “Hello, James, I’m Patricia Salvi, I’ve come to pick up my book,” she said in a friendly and melodious voice. There were three questions I could have asked and asked only one: “What book is that?” “Oh, come on now, James,” she began in a teasing tone. “You know, Almayer’s Folly. I need it back now. I could come in and wait a little while you look.” Her voice was mid-Atlantic with a tang of what I took to be Spanish, maybe Portuguese. Somebody well-travelled, at ease in many countries. I was confused by what she said and the half-demand to come in. My wits kicked in a few seconds later, some synaptic processes having made a decision. “No, it’s OK. I know where the book is. I’ll get it for you.” With that I shut the door on her still smiling face. Why I shut the door I don’t know, it was a reflex, some sixth sense that all was not what it should be. I went to the bookshelf, pulled out the book like an automaton and returned to the door, pausing before opening again. When I did open the door again I found her in exactly the same position. The book was given to her without ceremony or any chatty exchanges. Our fingers touched briefly; hers were cold. “Thank you, James. See you again sometime soon.” With this, the smile too, she turned and glided off more than walked. Afterwards I felt shaken by this strange visit and had a stiff drink, a nice malt whisky that slipped down easily. I had another one. Then I asked myself the other questions. How did she know my name? How did she know where to find me? Another question was: How could she even know I had the book? I decided to stay home for a few days and on the third a red envelope dropped through the letterbox. Inside was one of those greetings cards that are blank so you can write your own message. The picture on the front was the Gauguin, and I saw for the first time that the Almayer’s Folly publishers had only used a detail for the cover. To the right of the painting is a man chopping wood. I really couldn’t work out the significance of this figure. The card was signed ‘P’, nothing else. Inside the card were two airline tickets, dated for the middle of May around about my birthday. The first was a Delta flight from Los Angeles to Jakarta, capital of Indonesia. I noted the red part of the airline logo. The second ticket was a domestic flight with Lion Air, with an all red logo, from Jakarta to the city of Balkpapun in East Kalimatan, part of Indonesia on the island of Borneo, where Conrad's book was set. I have written all this to try and explain everything to myself. It is now barely two weeks to flight time. Another red envelope dropped through the letterbox this morning. I assume it will say how I get to Los Angeles. I reach for the malt and pour a good measure. James Bell James Bell is originally from Scotland and now lives in France where he contributes photography and non-fiction to an English language journal. Also a poet he has published two collections to date and continues to publish work online and terrestrially. He was highly commended in the 2016 Tears In The Fence Flash Fiction competition. Recent poetry can be found in the 2017 ebook anthology Flowers In The Machine from Poetry Kit, available as a free download. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|