|

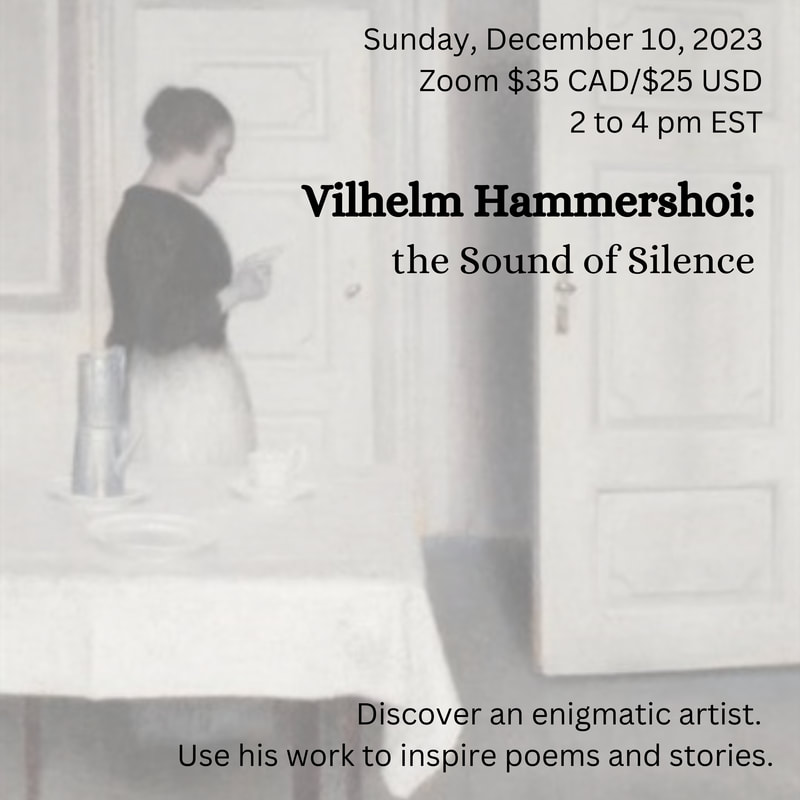

Join us next weekend to learn more about the enigmatic artist Vilhelm Hammershoi, and explore how his eerie empty artworks can inspire your stories or poetry.

Click image to learn more or sign up.

0 Comments

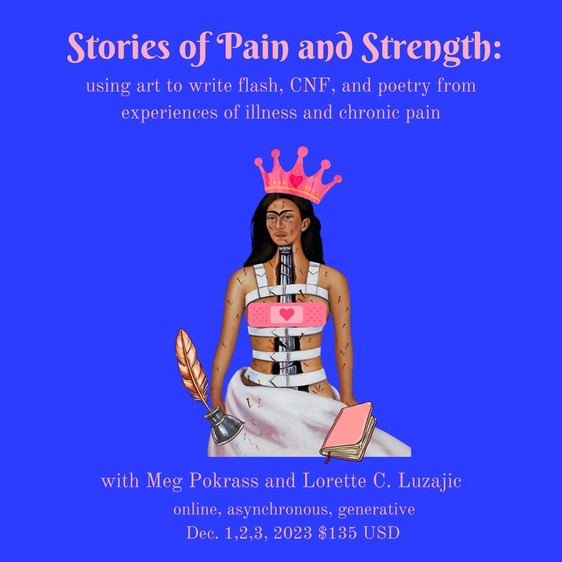

Northern Light Like the stinging lash of a sermon, I penetrate domestic corners – make a morality from a fallen receipt book. This chalk-faced maid has stolen a thimble. Her mistress scratches entreaties to a lover. He’s planted a seed in the pot of her womb. All things are made of my fire. I know every jut, sag and swell of them – how they fool themselves. I bleach stains from their sheets, make pewter shine like gold. What use those shutters of nailed oak? Every morning, they must push them wide, take the flood of me into their souls. I relish the crooked lay of those floor tiles, so black, so white like their religion. In this thin, northern air, I must temper my intentions. But I know how to flare a pin at the huisvrau’s throat, bring pearls to her ears. Along the dense tapestry that smothers her table, I seek what doesn’t show: tender fingers, girls’ eyes burned by stitch work. Dreamy maid, my Danae, my vessel. I snap you into shape – naer het leven – scoop out space for your thoughts. Look carefully. I’m offering you your face in that stained glass. Claire Booker Claire Booker lives near Brighton on the south coast of England. Her poems have been set to music, filmed, displayed on Guernsey buses and Worthing Pier, published in magazines including Ambit, Magma, the Rialto and Stand. Her work has been twice nominated for Forward Best Individual Poem, and for a Pushcart. Two of her poems were performed simultaneously at six venues (in Scotland, England and Portugal) as part of The Solstice Shorts Festival. Her first collection, inspired by the South Downs National Park, is A Pocketful of Chalk and available from Arachne Press. Her pamphlets are The Bone That Sang (Indigo Dreams) and Later There Will Be Postcards (Green Bottle Press). More info at www.bookerplays.co.uk Cancerous Sneak after Octopus Mosaic, by Iulian Moldovan (Romanian) 2016 You slip through collarbone portal, past muscle sweep and loiter behind cloisters of tissue. Your tentacles break boundaries of old milky ways as you dance on to new coverts. One day I see you fluttering on screen, an image out of the blue, hiding in plain sight. You light up like an algal bloom of plankton, catch my eye and uncurl a tentacle before scurrying off into tangled kelp fronds, strands tailing behind you like mermaid locks. Do I even know you? Are you a quiet yet hungry friend, all heart and hug, who’s already settled in? Should we cling to each other and swim further in? Should we quick-step in ever increasing circles together? The experts counsel your immediate capture and eviction before you multiply and take over, tile by tile, one cell at a time. They sharpen their knives. Now rubbery thoughts fill my mind. I wonder when you first planted your Judas kiss and all else fell back in awe. As the beat accelerates, let me whisper a warning to you of the upcoming chase with harpoons, pellets and poison. I know you will leave your suction marks – stitched seams, yellow-brown bruises, laser scorch, blood-raw skin – and that I too will become a shape-shifter, but I’m sorry, I have to overtake you, stop you in your tracks, smack you down, pluck you out. Helen Freeman Helen Freeman started writing poetry whilst recovering from an accident in Oman and got hooked. She has poems published on sites like Clear Poetry, Open Mouse, Algebra of Owls and The Ekphrastic Review. She has spent many years in East Africa and the Arabian Gulf, but currently lives in Durham, England. Instagram @chemchemi.hf White Centre, Mark Rothko, 1957 We’ve heard enough about him to know he never existed. Now here’s a picture of him. He’s a glowing white substance that like ectoplasm isn’t solid or liquid or gas. Even in a painting he doesn’t stay still, being made of restless waves, the way waves are of made of whatever they’re passing through and are always passing, though these are right here. He’s compressed between two soft masses of orange just a little more solid than he is. These must be the guards, leading the condemned to the place of execution. Or perhaps they’re the details of being human. Will there be enough money? What should we have for dinner? Do we really have to die? It never lets up, being human, never relents its grip, which is tight enough to hold a ghost prisoner. Yet he rides his own light out of the painting, not restrained but sped on his way by the dark shades of orange, as a prisoner on his way to the scaffold meets the eye of anyone who sees him and in that instant escapes into their recognition, of who he is, that now he lives in them, that he was born there and never lived anywhere else, even as the guards tighten their grip, so they suppose, on him. Peter Cashorali Peter is a queer psychotherapist, previously working in community mental health and HIV/AIDS, now in private practice in Portland and Los Angeles. He is the author of two books, Gay Fairy Tales (HarperSanFranciso 1995) and Gay Folk and Fairy Tales (Faber and Faber, 1997). He has lived through addiction, multiple bereavements and the transitions from youth to midlife and midlife to old age and believes you can too. Aspecta Medusa, or Why I Let Him To lose your head over a boy to want him so badly you’d offer anything. I mean throat. I mean tongue. What I mean is, even Spring can be talked into flowering too early. Of course, I’d heard the stories about him. My sisters had been around, were familiar. They exchanged knowing glances as they hummed their dirge, each of us jockeying for the mirror before school. Mama used to call it putting on our faces. The cupid lips. The apple cheeks. All us girls trying to get it just right. The look. To be the fruit. To be the one he’d pick. On our first date, strolling home from the movies, night perfumed with pear and fig and his arm locked around my neck, he joked about a threesome with the redhead slinging popcorn. From between the blades of sweet grass, crickets fluted a warning. I punched him in the arm, lightly. Laughed as girls will. Lightly. He hung his jacket around my shoulders But next time I kept my eye on her. What I want to say is: after the first time I could have left him except he started crying about his dead-beat dad, about shouldering the world’s weight. I think he wanted to love me. When he placed my hand over the grief blazing in his chest I could practically see through him. How many girls get to heal a God? A good head on her shoulders, that’s what they used to say about me. As if being sensible can protect a girl. As if a foolish girl deserves less blame. The night he ended things, I was asleep, dreaming of my sisters in our mother’s kitchen, the three of us gathered at her skirts. She was singing, rolling out sugared dough, our stomachs cramping with desire. When she looked away, I snuck just a morsel, its sweetness still melting my tongue when I opened my eyes and saw his sword drawn, tears polishing his hero’s jaw. I pulled aside my collar, turned my head into the pillow. Made it easier for him. Elizabeth Johnston Ambrose Elizabeth Johnston Ambrose's work appears in The Atlantic, McSweeney’s, Mom Egg Review, Emrys, Women Studies Quarterly, Feminist Formations, and Room, among others. She is the author of two chapbooks: Wild Things, (Main Street Rag, 2021) and Imago, Dei (Rattle Chapbook Poetry Prize, 2022). A community college professor and co-founder of the Rochester-based writing group Straw Mat Writers, she lives in Rochester, NY, with her partner, two daughters, and four rescue animals. the bride reflects Before I married, I don’t believe I thought of myself in third person - it happened then [laughs]. I suppose I awoke to the knowledge that I was the focus of it all: the event of marriage, of course, but also the act - what is a bride if not the centre, the final destination? And how could I experience that, being her? I needed to detach myself, somehow, from self-consciousness, and become pure object. As soon as I understood that, it was a heightened state - aroused, yes, that - but other things too. I felt a kind of wisdom descend, a knowledge that was timeless, prophetic even, and both blessing and a kind of curse [laughs] because it was so very sombre! And I watched my body peel away from its old ways, become a vessel, to be surveyed and turned about and, yes, violated, and I saw it all, as has happened to all those brides before me, myself coming, stepping through ruins, out into the light. Julie Runacres Recently retired, Julie Runacres taught English language, literature and creative writing at schools in Oxford and West London. Her poems have appeared in journals in the UK and the US, though she writes chiefly for wellbeing and a distraction from living in the UK. Join Meg Pokrass and Lorette C. Luzajic next weekend for a very special asynchronous 3-day workshop on themes of chronic pain and illness. Both women have experienced profoundly debilitating health issues and know how common this experience is. Nevertheless, it is almost taboo to talk about our relationship to our bodies and tell our truth about pain, fear, mortality, grief, resentment, hope, medical trauma, medical gaslighting, relationships, sexuality, moods, and the various transformations we undergo.

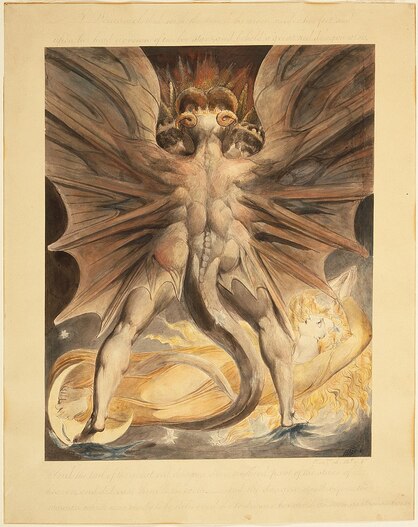

This is a special space to write on these themes in any way that moves you. We will write memoir, microfiction, and poetry, as you are inspired. Your work can be whatever you need it to be: angry, hopeful, triumphant, or defeated. You can write true experiences or use the themes to fuel complex, well-rounded, realistic characters and scenes. You can be funny or furious. You can focus on the strength or the pain, as needed. This is an opportunity to process and honour your experiences and all the emotions that go with them. For inspiration, we will look at an optional reading list on the subject and related themes. We will look at a variety of artworks by artists who struggled with chronic pain or serious illnesses. We will use the creativity of others to access our own deep well of experience and expression. This workshop will take place over several days, working independently and connecting with each other in a private Facebook group. Join us! Click image above or here to sign up or view more information. Rise She doesn’t know her strength, not yet. She’s young and modest in her ways. Her face is mild. The dragon likes to think that he has won; his wings are stretched and taut, his eyes are wild, his legs are spread in muscular display – the thick tail thumps the floor in victory. She doesn’t look. Her wide-eyed gaze is raised, as are her hands, appealing. Please, help me! Whatever answers fills her soul with light, which radiates through dress and skin and hair. She hasn’t lost. One day she’s going to rise, no matter how much threat the fiend might bear. For in this big reveal, his battle pose, there is no might; only his weakness shows. ** Kills It comes to her like something out of Hell: Anxiety. This beast beside the bed. Its mouths emit a never-ending yell; its poison seeps inside her pounding head. All truth is twisted. Gold is turned to grey, to match its shade, the tarnished, tinged with blood, her blood. It likes to drain her, every day. All that she is, lies trampled in the mud. There has to be a remedy for this, a reason found, a diagnosis, pills, the monster slain, a prince’s waking kiss, before it strikes – the last attack that kills. F.F. Teague F.F. Teague (Fliss) is a copyeditor/copywriter by day and a poet/composer come nightfall. She lives in Pittville, a suburb of Cheltenham (UK). Her poetry features regularly in the Spotlight of The HyperTexts; she has also been published by a number of other journals such as Snakeskin, Pulsebeat, Lighten Up Online, Amethyst Review, and a local Morris dancing group. Her interests include art, film, and photography. Artists and Women and Light “It’s all about light,” said Vermeer. “Oh, I agree,” said Monet. “Light and how it changes minute by minute. Almost as if it were being swept up and carried along by the wind itself.” “Oh, but I prefer the constancy of light,” said Vermeer, “how it is like whitewash clinging to the almost flat wall, a sheet of light sliding so slowly, so carefully to the floor. And why did you hide your wife from the light?” he asked. “Look at my maiden, her face sculpted into real dimensions, rounded, inviting you to run your hand over her forehead, down the curve of her cheek. Look at her white arm, dissecting the dark floor of my painting from the white wall and its luminous work.” “Oh, but that was the very idea, Johannes,” said Claude, “that was the idea—to have her head shaded, the dark parasol her crown, her face beaming back at us and highlighted by being in and of the shade but lightened by the aureole of clouds and sky and her skirt billowing brightly in the wind. Look at our son, in the background, lighted just as she, tied to her in this way so completely. That was the idea, you see, to make her stand out - set in light but apart from it, special, striking and unique in a light all her own, not the brilliant light of day, but her own warm and living light.” “Say, now, old, fellows, it is so much simpler than that,” said Warhol. “These days we artists dictate the light. We snap on the switch, adjust the clamp, angle the reflecting foil, spotlight the face. Or even simply imagine doing it. Look at Marilyn. Surrounded by gold, but more luminous than gold herself, her hair the brashness of fool’s gold. You see, the background, tarnished though it may be, asserts her claim to royalty, but the yellow hair, the pink face, both cast some doubt. Here is light manipulated to tell a new tale.” “Oh, but your light is so brazen,” said Vermeer, “it does not love your subject.” “And your light is neither realistic nor impressionistic,” said Monet, “it does not let us imagine her alive in sunlight. It neither revels in her nor reveals her at all.” “Ah, but that is the point,” replied Warhol, “that is the whole point.” Roy Beckemeyer Roy J. Beckemeyer’s fifth and latest book of poetry is The Currency of His Light, (Turning Plow Press, 2023). Beckemeyer’s work has been nominated for Pushcart and Best of the Net awards and has appeared in Best Small Fictions 2019. He has designed and built airplanes, discovered and named fossils of Palaeozoic insect species, and has traveled the world. Beckemeyer lives with and for his wife of 61 years, Pat, in Wichita, Kansas. His author’s page is at royjbeckemeyer.com. Ghostwriting the Winter scanning the dark pines helps me forget just for once I am getting old if I had a voice I would echo crows to shake branches off the trees how the winter sun freezes on the path ahead shadows of a ghost the frosting of ice becomes a polished mirror flowering snowflakes my blood on the ice marked the place where I toppled youngsters slide laughing lonesome butterflies visit the poet Basho what do they tell him my remembered loves like wings torn from butterflies for a memento one caterpillar wove a cocoon and vanished a textbook on life I think like a child but more than seventy now the moon almost full tracking that full moon seems an old tragedy played without any masks watching the moon change until a cloud flotilla gives me needed rest as snow falls on snow my dreams pile up on past dreams sleepless more and more Royal Rhodes Royal Rhodes taught global religions for almost forty years at Kenyon College. His poems have appeared in multiple literary journals, including: The Ekphrastic Review, The Chained Muse, Autumn Sky Poetry, The Lyric, and elsewhere. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|