|

0 Comments

Une Ville Abandonée A pedestal shorn of its statue, the sea’s encroachment, eye socket windows, absentees. Wind, on the banlieue. The reek of medieval atmosphere. Belfries, the unringing of bells, the town square, the broken parapet, the tumbleweed street. Here, all shadows in the sun, here the last man. Ask where the people have gone; ask and the answers trail off on the breeze. The sky lowers whiteness, a morgue sheet. Cobblestones hold the clatter of clogs: stored recordings. Doors, no doorknobs or latches. Shutters are shut blind and all is static. This, my future ennui. A shrine, relics, where the town’s your shroud, wraps itself round your recluse heart, occult pulse, your spectral hood. Alone on a bridge, you’re a beguine or anchorite, then Ophelia: your face ashen, hair camouflaged, sprawling. I see myself sketch your vignette, as gables double themselves over quays. This grief has yet to happen: a lock of hair in my pocket, the sea rising up the church spire. The sleep of poppies drifts through me, with you in exile, a deposed queen. Patrick Wright Patrick Wright has been shortlisted for the Bridport Prize. His poems have been published in several magazines, most recently Agenda, Poetry London, Iota, and Brittle Star. He teaches Creative Writing at the Open University. Leda

Denied access to her love anew, Zeus sought other means to possess her. Hidden in the marsh, he tracked her: His golden pinions brushing frantically against her thighs, pulling her apart. The cruel speculum of his beak penetrated, devouring her soul as she cried out: no. no. But The Swan is not god, and though she couldn’t retrieve what he thieved, the staggering girl (our queen) closed her shaking hands around his downy neck; wringing fiercely, she silenced him at last. Molly Cimikoski Molly Cimikoski was born and raised in beautiful New Hampshire, but now spends her days in sunny Santa Monica, California. She recently completed her master's degree in English and Creative Writing from Southern New Hampshire University and is pursuing her goal of becoming a professor. A Tour through Washington’s Holocaust Museum

My God, I thought I’d seen the worst of it-- shorn scalps and leathered limbs left mangled in a bed of bough, ashen stone—a fire pit. What must have been a beech-wood ark was locked and lit aflame, spewing smoke in great white bluffs. The crimson dusk. Victims trapped inside, alive. And beyond that stunning photograph, hard artifacts, culled from slums and slaughter grounds, now span these three museum floors. I press forward, wading through empty pairs of infant shoes and curly locks of hair, mug shots, portraits of Eishishok folk ascending up a tower, toward a light of Olam Haba. Individuals—a single life began as a precious mouth, puckered for her mother’s breast, and expired when her lips turned grey and cold, fissured, schlepped out to pile like kindling in a killing field. Selfsame individuals. Our crowd descends the low-lit middle floor to the model Auschwitz Crematorium. And you’d thought you’d seen the worst of it. Some thousand Jews hop off the cattle car and file glumly past the plaster guards, descend the stairwell to a bleached-white floor where tattered schloks and bare hides plop, where mothers shush and nudge their kinder down another concrete ark. Are they ghosts? Can they hear the bustle under shower heads, the patter of the thousand feet that fell before? The steel hatch locks. Pellets drop. White wisps sizzle out the vent to rising shrills and searing flesh and wilting kinder buried under mounds. A million pleas have rung these walls and still you stand there, deaf and dumb-struck, looking down. John Scott Dewey John Scott Dewey is a husband, father, fiction writer, poet, and middle school English teacher living on the Eastern Shore of Maryland. He received his MA in Writing from Johns Hopkins University. His fiction has been recently featured in Fjords Review, The Delmarva Review, and The Wilderness House Literary Review. Green Boots

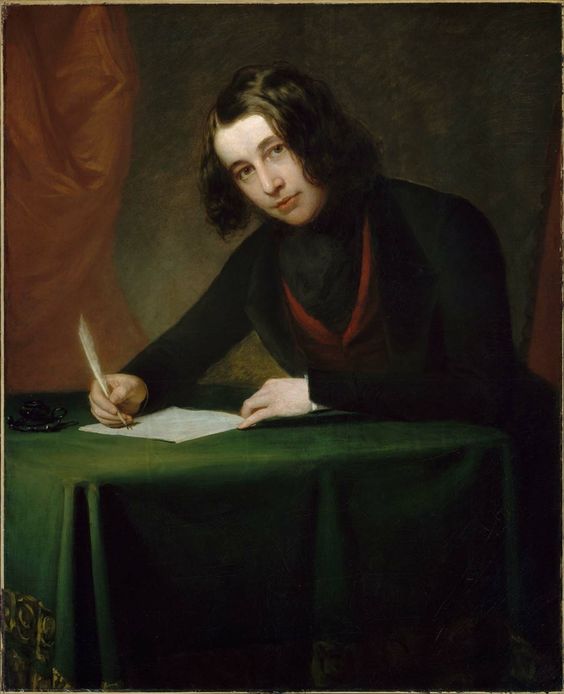

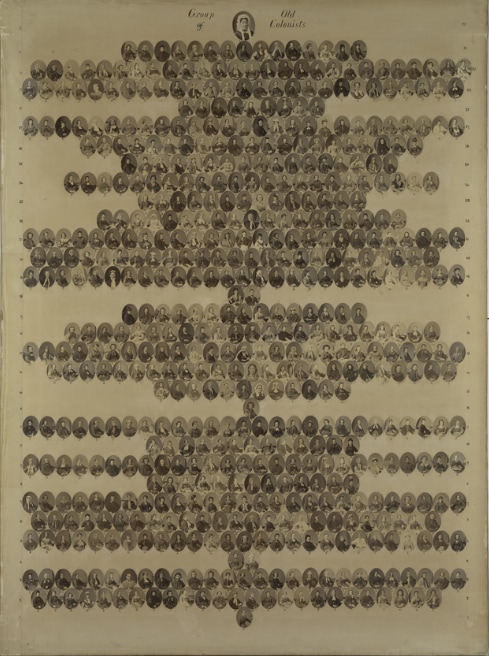

(For Tsewang Paljor and the other lost members of the expedition) Perhaps there are places we are not meant to go despite the allure of the untouched and untamed. Are all indulgences rightfully ours? Wasn’t Lot’s wife proof that we’re not always at liberty to see? I’m sure you didn’t mean to end your life as a landmark. Since ‘96, your green Koflach boots a warning to others: Everest takes, whether you are willing to give, or not. In an alcove made of limestone, climbers use you as a gauge. How much farther to the summit-- how much closer to God? Carol McMahon Carol McMahon is a teacher and poet who has been published in various journals (Prodigal, IthacaLit, Unlost Journal, The Wild Word, Blue Collar Review) and has a chapbook, On Any Given Day, published by FootHills Press. McMahon received an MFA in Poetry from the Rainier Writing Workshop in Washington State and when not teaching, reading or writing can be found out trail-running or on the water rowing. The Red Monk Rachel had begun to hear a call within her, an uncomfortable and eerie voice urging her to transcend her life and fill herself up with a food she had not tasted. The feeling frightened her and initially made her think she was going mad, but soon she began to believe that her condition was not madness but something mystical, outside the normal state of consciousness. The inner call wanted her to find or be something new, as if her real life was elsewhere. After reading about the sacred sites in India, Rachel believed that India had the answer. Her salvation would be in the holy shrines in the middle of the street, the river Ganges that could purge and purify, the temples and caves that were sanctuaries of holy people for centuries, the profound stone carvings and painted messages on their walls, the monks and nuns who wander the sacred grounds who could guide one to a higher life, and the retreats led by gurus with possible answers to her plight, perhaps bringing some kind of enlightenment. Her husband Murray frankly preferred a holiday in Mexico or Costa Rica, but he knew that going to India was an obsession for her. In her state of mind, he didn’t want her to go without him. * The Ellora caves were their last stop on an extended tour around sacred India. They had visited Amritsar, the Ajanta Caves, Kanchipuram, Sanchi, Allahabad, Khajuraho, Mount Shatrunjaya, the Palitana Temples of Gujarat, and Varanasi. After completing this journey through so many sites of supposed spiritual power, Rachel had grown more and more anxious and sometimes sick from the mounting confusion about her life that had driven her to India. Now, at Ellora, she could barely move from what she believed was a fear of the next stage or of no resolution. Despite this sense of dread, she was determined not to run and return home; she would confront this voice that beckoned. Murray roamed with the other tourists, amazed at how the artists had carved such beauty out of hills, but he did not venture beyond that observation and had no revelation. To him these carvings were like fairy tales told in stone; they were great art, but art that meant nothing to him because he was not Hindu, Buddhist or Jain, and had no acquaintance with the stories of Vishnu, Krishna, Ganga, Brahman, Parvati, Shiva, and the many other divine manifestations. Rachel sat cross-legged and gazed at the walls within the eighth century Kailasanatha Temple, a multi-storied structure much larger than the Parthenon carved out of a giant basalt hill from the top down and dedicated to Shiva. The magnificence of the carvings and sculpture depicting Ramayana and the Mahabharata tales was overwhelming not only because the exotic mystery and majesty of the monumental stone art were undeniable, but because she believed that the art had many stories to tell that could transform her as it had apparently transformed others. Walking around, sitting on the ledges, or squatting were also nuns and monks in many coloured garments. One of them hidden in the shadows in an orange robe had caught her eye. In the Lotus position he sat, reciting a chant she could barely hear. On the ground beside him was a book with worn covers. She stared at him for some time. At least twenty minutes passed while she waited for him to finish his ritual and emerge from his trance. Finally he stopped and turned toward her. When Rachel looked at his eyes, she saw the reflection of the figures of the sculpture in them from the nearby temple. “They move, you know, and communicate,” he said to her. “Shiva not only expresses reality through those tales but brings them to life and guides you, if you are ready.” “What?” Rachel said, somewhat surprised at how he had skipped pleasantries and spoke to her as if he had known her for many years. He pointed at the sculpted friezes. “If you come at a certain time, and if you are in a certain state of mind, you can see them move and hear them talk to you in your mind. When that happens, you’ve felt something of reality and it will draw you into the transcendent realm they represent. It’s like the effect of profound music. You become filled up with special harmonic patterns which move you away from your humdrum existence. Art becomes a vehicle for change.” Rachel nodded, not fully sure what he meant. Just then she noticed another monk in a red robe leaning on the wall with a smirk on his face. “Don’t believe a word he says,” the red monk said, “or any of them for that matter. Their spiritual condition more reflects the ruins than the inner spiritual forces of long ago. Most of them are beggars, preying upon tourists, pretending to know something profound.” “Most of them?” Rachel asked. “Yes,” the red monk said. “Some are like this fellow, sad searchers.” “And who are you?” “I’m someone searching for truth,” the orange robed monk said. “No,” Rachel said, “I was asking the red robed monk.” “You see the red monk?” the orange monk asked. Rachel nodded. “He speaks to you?” She nodded again. “But how could that be? You’re a…a…tourist.” “I want to…” Rachel began to speak. “You want to what?” the red monk interrupted. “That is your husband?” the red monk continued, pointing at Murray, who was clearly watching her while looking at the temple. She nodded. “Does he know you’re tired of your life?” the red monk asked. “What’s he saying, the red monk?” the orange monk asked. The red monk moved closer to the orange monk and sat in the diamond pose directly in front of him. “I didn’t say that I was tired of my life,” Rachel said to the red robed monk, “I was going to say that I want to know…” “Know? Know?” the orange monk interrupted upon hearing the word ‘know.’ “Is he talking about divine knowledge? Tell me. What does he say about divine knowledge? How do we know? Is he commenting on the Vedas?” The orange monk stood up. “Unfortunately,” the red monk said, still sitting, “so many poor innocent people talk to these jokers seeking some spiritual solace. Only a very few can help them.” “Ask him about how knowledge…,” the orange monk said. “Tell him nothing,” the red monk said. “I love my husband,” Rachel explained to the red monk, “but my life seems so hollow, and I need to find what will cure me of this emptiness, or inspire me, because I’m hurting so much that often I can’t breathe. Something inside is calling me to something greater. My soul seems separate from me.” “Interesting,” the red monk mumbled. “Are you sure it’s not spiritual illusion?” “Why are you so negative?” she asked. “You belittle other monks, you doubt my experience. No, it’s not illusion. I know the difference. It’s something quite real, too real, on fire real.” “Ah, reality,” the red monk said. “I think you may be burning up because you haven’t developed your own reality. First develop that to the fullest, then take the next step. To grow you must carefully nurture your seed. To fly you must crawl out of your cocoon.” “Don’t talk to him,” the orange monk said. “He tries to keep people away from the temple. He thinks everyone is unworthy. Did he mention reality?” “Is your real as real as mine?” the red monk asked Rachel as he laughed. He smiled, stood up, and started to walk away. “Yes, yes,” she said, following after the red monk. “Where you going?” the orange monk called after her. “I’m following the red monk,” she said. Rachel chased after him but the red monk disappeared around the corner of a temple. “You can’t follow him,” the orange monk said. “He has no followers. He’s a guardian.” The orange monk sat again on the ground in another shadowed area and Rachel joined him. They stared at each other for a brief period before he spoke. “You’re not from India?” he asked. She shook her head. “Neither am I. Three years ago I was helping my family with their restaurant and I told my parents I wanted to visit my grandparents in Aurangabad. So I traveled to India and I lived with my grandparents for a time but only to prepare. Then I began this life, became what you see. I had the yearning and the call and what I now describe as the need for union with the other.” A long pause occurred between them. “Who is the red monk?” Rachel asked. The orange monk grimaced. “Who? There is no ‘who.’ He’s like the creatures who guard the temples. All ye without pure intentions and heart, stay away! He scares people who see him.” “What’s he guarding?” “What’s real,” the red monk answered, suddenly appearing again from around the corner of the temple. “You believe?” Rachel asked the red monk. “No, I don’t believe what most of them believe,” the red monk said, “but I know what’s real. I scoff, I ridicule, I disagree, and I denounce because there’s nothing here for them. It’s all in their heads. I want them gone.” “But you’re in a monk’s robe,” Rachel said. “I am a monk. The others I must defrock so that they leave the space.” “Don’t listen to him,” the orange robe said. “You have a legitimate yearning.” “How would he know?!” the red monk said. “This area should be empty and at peace. Instead these predators prowl around it the way the tigers once did at Ajanta.” “I’m saying you’re not alone,” the orange monk said to Rachel. “There’s a hunger in many of us, a lacking…” “A lacking?” Rachel asked. “Yes, a lack of life, of that life,” the orange monk said, pointing to the temple walls, “…of…” “…of reality!” the red monk said. “…truth,” the orange monk concluded, “and that—what those stories portray and give and teach—gives me life!” “Oh Brahman!” the red monk mocked. “They’re just carvings by some poor artists who had nothing else to do but pray, recite, read scripture, carve, sleep; then again, pray, recite, read scripture, and carve, and occasionally eat. For years! They were devotees but few experienced the profound ways. I don’t demean them. They were great artists, devotees, but few of them had a grasp of what they carved. They were under the spell of the muse, and did its bidding.” The orange monk stood up and placed his face within inches of the frieze. “I know what the red monk thinks. He thinks for almost everyone they’re just carved stone. Yet he’s wrong. Why is he part of it if they’re just carved stone? Art is the greatest and most profound philosophy and no one can deny what I feel. Each day, hours every day, I meditate and chant and try to overcome the walls that block progress and remove the garbage in my soul. Only before them, here, do I sense progress.” He stopped and turned around to face her. “That’s my quest,” the orange monk said. “I have nothing else to offer you.” “That quest has little value for you,” the red monk said to her. “Take nothing from him. He’s creating it himself.” “But you have advanced....” Rachel said to the orange monk. “Advanced?” the red monk interjected. “There’s no scale of achievement. You’re either on land or in the water. The challenge is get to land, then stay on land and not drown in the water.” “But after so many hours and days of contemplation,” Rachel said, somewhat in awe of what the orange monk was struggling to achieve. “Months! Years!” the red monk said. “Who cares? So what. Time has no meaning in this space.” “All I have is one fact,” the orange monk said. “I have heard its call: I know that it is there, that there is a realm, an extraordinary plane, and it’s expressed in these sculptures, in this place. Here there is a portal, a space, and I shall find it and shut all of the doors preventing my way out. If it’s not true, why is the red monk here? Ask him that?” “And those others?” Rachel pointed to monks and nuns in yellow and orange robes. “They are chanting, reading scripture, and meditating. Are they all like you?” “I don’t know,” the orange monk said. “Some of them are like him,” the red monk said, “but some of them are scam artists. But he’s right about one thing. There’s an extraordinary dimension. And I am here, and I am real. But he struggles too much.” “You chant, you read scripture, you meditate,” Rachel said. “Just tools,” the orange monk said; “but tools don’t indicate I know anything or have found anything special. I’m slowly erasing what I lack by opening the doors that lock me out. I’m creating another kind of emptiness, the emptiness inside the seed of the great oak tree that can one day produce within me an oak tree of transcendence.” “Must you do this in India?” she asked. “Of course not,” the red monk answered. “Do you think reality has a location?” “Yes, I must,” the orange robe replied. “My old life was a life of wandering from my true state. Going back to where I grew up forces me to overcome too many obstacles and will fill me up with what has no depth and was a lie, the garbage of my existence. Why should I try to make that false life work? Here there is something to find, something to keep me searching, the emptiness in the seed of the oak tree.” On hearing these words, words that expressed the raw truth of her own dilemma, Rachel suddenly broke down, crumbled to the ground and held her head in her hands, covering her face. When she removed her hands, the orange monk had left. Instead Murray stood before her and the red monk was nearby. “Oh Brahman, don’t listen to the orange monk’s words,” the red monk consoled; “they’re just fancy abstractions that have no existence. He can’t articulate any of this. The man is trying, I grant you, but he’s hiding what no one do or say. He must transcend the words and the thoughts and the actions. But he won’t and now he has a bunch of excuses!” “What’s wrong?” Murray asked. “I saw you talking to that monk. What did he say?” “Monk?” Rachel asked. “You mean monks. There were two.” “No, I saw only a fellow with an orange robe.” “Nothing,” Rachel replied and began to cry. “What is it?” Murray asked, putting his arm around her. Her eyes in tears and her face red from despair, Rachel looked at the concerned face of her husband. “Nothing,” she said. “Really nothing. Don’t worry. I’m just tired. You didn’t see the red robed monk?” Murray shook his head. “Whose book is this?” Murray said, picking it up. “Could I see it?” Rachel asked. Rachel opened up the battered covers. No writing or print was inside. It was a large collection of white empty pages. The orange monk had not recorded a single experience or observation. She ran after the orange robed monk to return the book to him. She searched for him throughout the complex, but she could not see him in any direction and returned to the temple. The orange monk eventually returned and faced the temple carvings next to her. She handed him his book. By then the afternoon shadows were beginning to spread across the walls, each of the figures on the friezes seeming to glare at her. One in particular had the face of the red robed monk. Rachel became mesmerized by the poses and motions of what she saw on the wall. The more she focused on the face of the red robed monk, the more she experienced an ineffable sense of release and enlightenment, but it was only a quick sensation, as if a door opened, she glimpsed something wonderful within, and then the door closed. She pointed out the stony face to the orange monk, but he did not understand what she meant. He was already in meditation with his eyes closed. Murray had sat down beside her, but his eyes were on his wife because her face was slowly losing colour until it finally had a greyish tone. It lasted for a minute and then her colour returned. She looked at Murray and smiled. “Are you okay?” Murray asked. “I’m fine. Let’s go.” “What happened?” Murray asked. “You looked like you were about to faint. Your face lost all colour.” She hugged Murray tightly and stared briefly at the orange robed monk, who had opened his eyes and perusing the frieze and chanting. “Not sure how to explain it,” she said. “So you’re happy we came to India?” Murray asked her. “Of course. A part of me shall never leave.” Hidden behind several carved figures in a crowd, on the wall with the red monk, unnoticeable to anyone, she saw a nun with a face not unlike her own. D.D. Renforth D. D. Renforth has published eight stories in the last year and is a graduate of Syracuse University, Duke University, and the University of Toronto (Ph.D). Renforth offered a year-long course that examined the transformative qualities of art. Women old colonists our auslander manifesto for an unadulterated space – companions in family history, too mature & silent to administer cartes de visite & left hanging cryptically, algebraically, among other mash-ups & ruins but, still, warum allein? the others from the Holborn gathering have come & are very pretty today / sleep becomes hard with the doctrines of gullies & glades exposed – at least have faith in this catalogue entry, a long winded way to ensure you are participated at, a testament to mild applause / every frayed cloth, blotchy forearm (heightened senses) expressed in mock woodgrain, the myth of symmetry underlying the repose of men / true charity is never holding country accountable for temperaments vanquished… besides which, the banquet was spoiled by the Gambier brothel story though in this age the feeling is more than mutual / oh my mind turns off too frequently / it is hard to distinguish what is patience in all this, patience losing measure by the season, is there even lustre in these experiences (advising cloves for teeth care, lips pursed will work here, make up for it with posture) / a season, an idea, united under abstractions felt – physiques are matter, trust to the depiction, no single painting can be guilty / hands folding & unfolding in the fug of March, voices of arts patrons ferment on inconceivable neighbours’ enthusiasm – more pressing is pastoral as a Prussian delineation now, familiarity endangered, contested vistas changed upon looking / childless men guessing at circuits, roundabout achievements in al- most engineering, them & us improvisers in terrain, intimacy, ‘local or universal’, relent to pose with compassion this eve / record of fitted smiles, a collage of isms / time to do this, swapping a face for a face, time to exist here remaining within token hierarchy / good-natured habitude leads to over-reliance on species memory to dis- engage Barnaby Smith

Barnaby Smith is a journalist, editor, poet and musician based in northern New South Wales, Australia. He can be found online at www.seededelsewhere.com Lesson from Nature

The cat’s bones hold it up in a field of flowers, spinal chord a stem for a head seeded with desire, ears’ leaves lifting to the hum of bees, the rise and fall of wings, paws delicate between stalks, awaiting mice and voles that will come, the serration of ribs, foliage, jaw, giving the light an edge with which to cut. The artist has hand-coloured two blooms, high and low, an homage to each gentle corolla, but haloed by the stripping sun, the bowed skull remains the focal point, hungry, hungry. Devon Balwit Devon Balwit is a writer and teacher from Portland, OR. She has two chapbooks forthcoming--'how the blessed travel' from Maverick Duck Press and 'Forms Most Marvelous' from dancing girl press. Her recent work has found many homes, among them: Oyez, The Cincinnati Review, Red Paint Hill, Timberline Review, Sow's Ear Poetry Review, Trailhead Review, and Oracle. On Whistler’s Nocturne: Blue and Gold—Southampton Water, 1872 In the busy harbour, wave-elbowed boats drop sail one night, turn as one to face imperfect perfect golden Cyclops. Sailors transfixed, all hands bewitched. Passing clouds scar lambent observer, hovering over light pierced skyline: harbour’s pub and inn, lamp and post-- meagre lucent offerings all. Hulking ships struck dumb in darkest dusk so blue, cloud spread sky felt as shadowed lapping water heard. Over all our Orphic moon hangs low, so much more than seen from earth, awe producing awe, age from age to age. Michelle Geoga Michelle Geoga is an 2017 MFAW candidate at the School of the Art Institute. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|