|

Benjamin Britten, Turn of the Screw After Christopher Palmer and Myfanwy Piper Each variation on the twelve-tone row turns a a dissonant screw on tonality so home keys seem unheimlich, common chords other-worldly, perfect fourths Diabolus in musica. Children’s voces angelicae turn Benedicite’s cross upside down and Lavender’s Blue’s all too blue. Their governess is lost in a labyrinth of scales from faux-Mozart Sonatas, leading nowhere but dead-ends while Quint’s sybaritic melisma is leading us to a gamelan lake where innocence is drowned far from C major’s haunted house and Miles’s sad little song: Malo: I would rather be Malo: in an apple tree Malo: than a naughty boy Malo: in adversity Jonathan Taylor Jonathan Taylor is an author, editor, lecturer and critic. His books include the novel Melissa (Salt, 2015), the memoir Take Me Home (Granta, 2007), and the poetry collection Musicolepsy (Shoestring, 2013). He directs the MA in Creative Writing at the University of Leicester. His website is www.jonathanptaylor.co.uk.

0 Comments

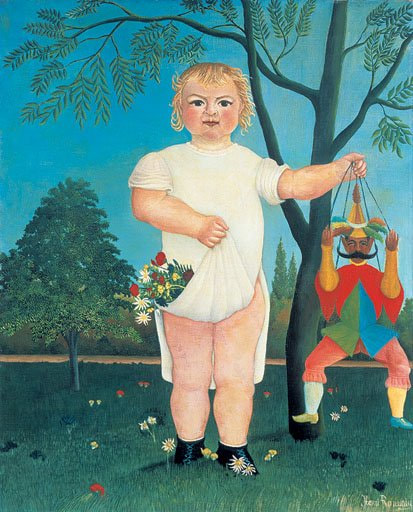

The Zianigo Frescoes Introduction Say that it’s just like life, say that each road (however long) is finally a dead end. Here, round every corner, a dead end. The whole place now, a mouldering dead end. A beautiful, a glorious dead end, where once, a thousand years or so ago, by some collective effort of the will, each dead end was a start, a whole new world: familiar changed to unfamiliar; solid to liquid; waking life to dream; and sordid, opportunist acts of trade to art. Art everywhere, stolen or made. Petty officials, pompous bureaucrats, rapacious merchants, every minor saint whose sleight of hand deceived the credulous – transmuted into art. So many years the city state maintained this high-wire act of the imagination. But one day gravity intervenes, let in by loss of confidence, or by its opposite, by chance or by decrepitude – who knows? The infinite horizons then retreat. The street that ends in water is no more a stepping off, but now a shutting down, a locking up, a turning in, until imagination’s grandiosity becomes grotesque. Follow me now – a right turn from the door… two minutes’ walk will take us to the water, with no choice but to turn left some three (four?) dozen paces more to this peculiar form of the dead end. The New World We are not welcome in this bright new world. Here is a motley wall of coloured backs, cold-shouldering, huddled, jostling for the view they’ve paid good money for – not queuing up as I had thought, to leave behind this dead- end old world. Then again, perhaps they are. Perhaps the sole escape is fantasy: a different, more lurid fantasy; a stronger, cheaper, baser drug; a Punch and Judy show, with cartoon violence substituting for what some might call the real, with its inherent violence. But there is always consequence. It seems they do not know that they are now the show, and though they turn their backs and put on masks, evade us in the sodden labyrinth, they are the show, fated to parody their opera, their art or – worse – themselves, for crowds come in their millions to gawp at the dead end, smell the decay first-hand, and watch the lot sink into the lagoon. See – Pulcinella’s now a citizen, escaped out of that show and into this, and ready to comport himself just like a model citizen. What could go wrong? Pulcinella in Love Assuming that the mask’s grotesquerie is worn to hide the beauty underneath, we’re equal in our joke of ugliness. But when the mask is moulded to the shape of true deformity, when the hooked nose fits snugly in the nasal cavity, and when no padding is required to make the hunched back and the wide-distended gut, democracy sneaks in at the back door, or anarchy, perhaps. And our outcast – the butt of every smug comedian’s joke – is free to grope aristocratic tit. So confident in her own beauty and her power, that she cannot comprehend another might be less well-bred, well-formed, and still be able to breathe the same air. But he knows what life feels like, and that it feels like this yielding, yet resistant, flesh. He’s waited all his life to fondle it. He’ll sing its praises in his swazzle voice. He’s going to squeeze, till it gives up its juice. Pulcinella’s Swing A rope is all it takes to stay aloft. No need for angels holding up the cloud to take the weight of bearded daddy-God, or levitating Spanish kings and queens, painted by daddy Giambattista on the ceiling of some chocolate box chapel. Now, looking up, the glory seen on high is a bulbous behind in white homespun. Now Pulcinella rules, not only in the worldly city, but in heaven above. Pulcinella’s Departure One day, there is no more revenge to take: not on aristocrats, fathers or gods, not on all the society, who made them clowns. Now Pulcinella comatose with drink assumes the pose of Hyacinth killed by Apollo’s discus. Now we all are Pulcinellas, all with the same mask, same dunce’s cap and same deformity, all quacking violent inanities. There is no one to overthrow, no one to blame for our shortcomings, but ourselves as we swill and cavort in our new world and drain all meaning and all beauty from existence. Unsustainable dead end! We need a scapegoat, but there’s only us poor Pulcinellas. One has got to go. The finger points… with back already slumped, already bearing this absurd new world’s guilt, he can only shuffle out of frame scratching his arse, outcast of the outcasts, the tragic hero of the comedy. Mike Farren Mike Farren’s poems have appeared in journals and anthologies, including The Interpreter's House, The High Window, and Valley Press's Anthology of Yorkshire Poetry. His debut pamphlet, ‘Pierrot and his mother’ was published by Templar Poetry. He publishes under the Ings Poetry imprint and hosts the Rhubarb open mic in Shipley, UK. Website: http://www.mikefarren.co.uk/ Twitter: @mikefarren Together We Are

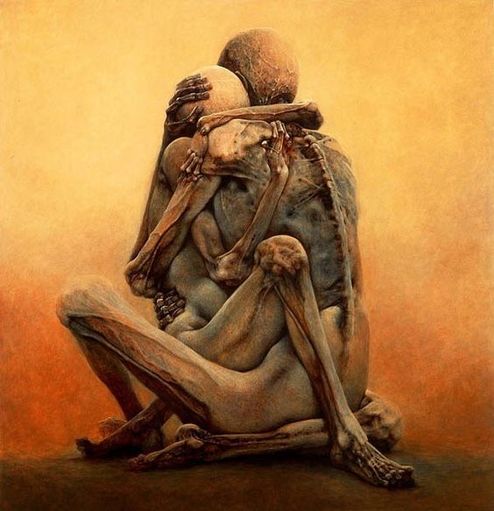

Huddled in the clutch of love so long our bones stand out bare, uncovered by the soft sweet flesh that was ignited in the furnace of our consummation. Like paper in fire we flare up we curl into each other locked in intimate exclusion of anyone beyond our fierce embrace-- where we burn forever only for ourselves fused hip to hip, bone to bone incandescent, one body reinvented, reborn forged in the crucible of blind desire. Mary McCarthy This poem was written as part of the sex and art ekphrastic Valentine's Day challenge. Mary McCarthy has always been a writer, but spent most of her working life as a Registered Nurse. She has had work published in many on line and print journals, and has an e chapbook “Things I was Told Not to think About” available as a free download from Praxis Magazine online. Blue River (Rio Chama) – a Word Painting

I. Stony mesa sprawls across the land beyond the river; reclined here for centuries, an aging painted beauty burnt sienna and creviced in the sun. Rough blankets woven of umber and sepia rubble stippled sap green with juniper, higher up with piñon and oak, drape pleated across her torso. The blanket parts at her bony bent knees to reveal red rock skin wrinkled and sagging toward her feet; the river flows from between her thighs. II. The Río Chama flows constricted from the seam among hills, bends and twists upon herself, merges and separates, seeks a torturous, then smooth path, sings a symphony toward the Río Grande, the Gulf of Mexico. Cobalt mirror of sky with streaks of lapis and pearl disguises her origins-- vermilion silt from slick rock, sharp lunar black granules from basalt, china white glitters from sandstone, suspended in clear liquor distilled from cumulous clouds. Watercolors flow south from Georgia’s brushes down the serpentine riverbed. III. Manganese blue sky, a wash laid on behind and above the mesas with a flat, even brush. An invisible wind blows from hidden lips at the round earth’s imagined corner.* Scattered here and there, with a round, sable point, daubs of silver, pearlescent shimmers of cloud twist and stretch, sail and thread their ways across changing cerulean heavens. IV. Cottonwoods bury gnarled toes deep in sand and silt deposited on the outer bank of a sinuous, rocky curve where water drags her feet, slows her race to the Gulf, drops part of her gravelly burden. They drink the Río Chama, armor the banks against her insistent assault, these muscular trunks clothed in graphite gray, furrowed bark, raise sinewy arms, paint malachite green shadows on river’s skin. Supple silvery wrists and grasping bony fingers celebrate summer, clad in elbow-length viridian gloves. Gleaming leafy arrowheads dance on thin petioles before a downstream breeze, point now at the river—source of life-- now at the sun—absorb its energy. Secret in arrowhead-shaped shadows, a thin gilt brushstroke of cadmium yellow that will be their autumn raiment. V. On inside edge, embraced by looping curve of river’s sweep, lies young, smooth-skinned sand, swept down-river in glittering bits, deposited as water slows its path upon the moving curve, a simple wash of gritty ochre granules. She hosts a few equally young trees. Young and impressionable, she will lift her sandy skirts, shake loose twisted rootlets and rounded pebbles, migrate downstream at the sinuous whim of the ancient river’s change of direction, back and forth across the valley between rocky knees, muscular trunks, but always south toward Big Bend and the Gulf. Janet Ruth *phrase from John Donne’s Holy Sonnet 7 Janet Ruth is an emeritus research ornithologist, living in New Mexico. Her writing focuses on connections to the natural world. She has recent poems in Bird’s Thumb, Santa Fe Literary Review, two volumes of Poets Speak Anthology—HERS and WATER, and Weaving the Terrain: 100-Word Southwestern Poems. Janet and her husband have sought out and photographed New Mexico locations that Georgia O'Keeffe painted to experience for themselves the magic they hold. Ba’al Therefore, behold, the days are coming, declares the LORD, when this place will be called the Valley of Slaughter… What about now, this bright light born to darkness dead in the alley, for the sins of his father? This promise, this wide eyed marvel of a child, did anybody love him? An imaginative boy, someone said, just on his way to play basketball. The sacrifice of Isaac without the happy ending. Mama in her new car, before he’s even buried. Dad’s face, as hard and mean a face as there has ever been. What about now? Does Tyshawn matter? And where to, from here? The black bodies are piling up, burnt sacrifices on the altar of our microaggressions. Lorette C. Luzajic This poem was first published in the author's ekphrastic poetry collection, Aspartame. Lorette C. Luzajic is the founding editor of The Ekphrastic Review. She is a Toronto, Canada based visual artist who shows regularly at home and further afield. Visit her at www.mixedupmedia.ca. Drawing in Bolsena, or Writing

If we take the length and multiply it by this, the rectangle, like so. Not a circle, no, but here it is. And, too, the scrubbing out, the dirty eraser. And then these random thoughts, numbers, like the floaters across the eye’s surface or the contractor’s sonnet. This part of the mind opens and the hand works, moves across the paper the color of wet sand, the canvas, the space. Something like automatic writing, that parlor trick. Here, this, and the downward slant, trailing off, and the swish of bell-shaped skirt, tilt of table. Hush. And over here, nothing. Kelly R. Samuels Kelly R. Samuels lives and works as an adjunct English instructor near what some term the “west coast of Wisconsin.” Her poetry has been nominated for Best of the Net, and appeared online at apt, Off the Coast, Burningword and The Summerset Review. A Fist Curled, A Folded Wing

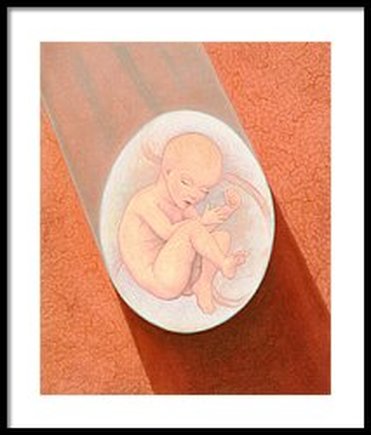

nautilus uterus cerebellum origami crooked smile tear drop neuron scorpion cochlea ear bud ocean Jennifer Bradpiece Jennifer Bradpiece was born and raised in the multifaceted muse, Los Angeles, where she still resides. She remains active in the Los Angeles writing and art scene, often collaborating with multi-media artists on projects. Her poetry has been published in various anthologies, journals, and online zines, including Redactions, Degenerate Literature, and The Common Ground Review. She has poetry forthcoming in Black Napkin, Nowhere Poetry, and NeosAlexandria: The Dark Ones Anthology among others. In 2016, her manuscript, Lullabies for End Times, was acknowledged as one the final ten favorites in the Paper Nautilus Debut Serious Chapbook Contest. To Celebrate the Baby

Dear Hope, Attached is a 20 page paper, “From Feathers to Fur: Theatrical Representations of Skin in the Medieval English Cycle Plays.” It was written by Amanda LiCastro. Do you remember her? She’s the niece of Mrs. Aftel, the lady with the cats who lives on Gardiner. Anyway, Amanda is getting her PhD in English at NYU and doing some extra writing on the side to help pay the bills. I’m sorry the last one didn’t work out but it could be your professor was just being picky. That man came highly recommended, as you know. Don’t stress over it. You probably still have the highest GPA at Kappa Phi. See if you can take the Algebra II class online over the summer because I have a guy who’s a math whiz and can do the whole thing for you on his computer. So glad you told us you’d prefer not to go to Florence over spring break before we went ahead and booked the trip. I know Paris is high on your wish list. Or would you rather spend March in the Caribbean? There’s a place called Dreams in Punta Cana where you can get massages and facials every single day. Mom sends her love. Please don’t be mad. She went to six different stores trying to find those Steve Madden boots you wanted but no luck! They’re completely out of stock online and she couldn’t locate them on ebay either. Are you absolutely sure you wouldn’t like them in brown because that we could do. She asked me to remind you to text us what you want us to bring when we come up next weekend. We will drive your car and take the train home. The mechanic fixed the entire front end and got the dents out of the passenger side door. It honestly looks just like new! Did your Flowers of the Month arrive on time? I know the orchid was a hit but Mom wanted to be sure you got the paper whites. They will brighten up your room. Also, your new phone got sent home instead of to school so we express mailed it to you and it should be there by tomorrow afternoon at the latest. And I put another $10,000 in your checking account, which should tide you over until break. Re voice lessons, why not if you have the time? Schedule them once a day if you need to so you’ll be ready for the upcoming Godspell audition. Well, baby doll, that’s all for now. Stay as sweet and beautiful as you are. Remember there’s no one as wonderful as you. All my Love, Dad Beth Sherman Beth Sherman has an MFA in creative writing from Queens College, where she teaches in the English department. Her fiction has been published in Portland Review, Black Fox Literary Magazine, Blue Lyra Review, SandyRiver Review, Gloom Cupboard, Delmarva Review, Panoplyzine, Sinkhole, and Sou’wester. Her poetry has been published in Lime Hawk, Gyroscope, Rust + Moth and Silver Birch Press. She is also a Pushcart nominee and has written five mystery novels. The Snail My father would use the salty brine from the olive jar as salad dressing, pouring it until a little pool formed at the bottom of his bowl, lettuce leaves ever so slightly swirling, like the dream I had last night where a snail circled softly around a pile of salt, but it did not melt, just climbed higher, and when I called to him to look he walked away, jangling the keys that dangled from the balloon-shaped leather keychain he used to hang on a hook by the front door of the army base house we lived in when I was four, where once I saw a real snail on our wide concrete sidewalk and crouched down low beneath the hot Oklahoma sun and watched it drag its slime across the shadow of my hair while my father started up the Volkswagon, his cigarette smoke swirling patiently from the window. Amie E. Reilly Amie E. Reilly is an adjunct professor in the English department at Sacred Heart University in Connecticut, where she lives with her husband and ten-year-old son. Her most recent work can be found at Fiction Advocate, The New Engagement, The Evansville Review, and Entropy. She also blogs at https://theshapeofme.blog/. Seven Questions: Artist Bobby Beausoleil Talks From Behind Bars With Anthony Stechyson

"Please appreciate my work, or not, solely on the basis of its merits as art. By doing so you are likely to learn more about the truth of who I am, if that is of interest to you, than in any other way." (Bobby Beausoleil in his own words, from his website) Bobby Beausoleil has been in jail for nearly half a century. In 1969, he was arrested for the murder of Gary Hinman, a crime that came to be associated with Charles Manson. Prior to the crime, Bobby Beausoleil was well known around San Francisco and Los Angeles as an artist, actor, and musician. He collaborated with the legendary filmmaker Kenneth Anger as an actor on the first iteration of Lucifer Rising. Beausoleil certainly didn’t let his incarceration get in the way of his artistic pursuits. After his incarceration, he continued creating works from prison: writing songs, recording albums (sometimes with instruments he built himself) and honing his skills as a visual artist; creating vivid and fascinating paintings, drawings, and watercolours. His art has been exhibited in various galleries and he regularly posts new creations on his website. Bobby answered a few questions about his art and his process for The Ekphrastic Review: Many visual artists draw inspiration from the world around them. You’ve been in prison since 1970. What inspires you? While I admire the work of some of the artists in prison who are inspired by their surroundings, I am not one of them. Rarely do I encounter anything in my immediate physical environment that moves me to produce a rendering in visual art that is anything close to a literal representation of it. But then, were I in an environment where I would be surrounded by beautiful natural vistas it's unlikely I would be inclined to produce artistic images of what I see. In either case, however, the surroundings may influence how I feel or what I imagine on the screen of my mind, and this will often move me to create art rooted in these visualizations or emotions. So you might say that my immediate surroundings may inspire my work indirectly. Describe your process, where do you paint? How do you obtain your materials? I like privacy when I'm working on visual art. Once in a while I may be invited to help paint a collaborative mural somewhere in the prison; in all other cases I work at a small table in my prison cell, usually at night when it is quieter. I am able to purchase some very limited types of art materials from outside vendors. In most California prisons the handicraft programs and art programs have faded away. This has severely limited access to art materials such as oil or acrylic paints and canvases, leaving as the only options things like graphite and coloured pencils, pastels, crayons, and paper art pads in smaller sizes. I have been able to finagle some larger sizes of art paper, and through experimentation I have learned how to make my own paints from the types of media that are permitted. I have a few brushes left over from when handicraft programs still existed. Where there's a will there's a way, as they say. I know guys who produce some amazing art using ballpoint pens, or dissolved instant coffee applied with cotton swabs. Cardboard from boxes found in trash cans is a canvas for some. Like a few other artists I have found in these places, my natural inclination is to veer away from influences that may inhibit a truly authentic artistic vision. How do your fellow inmates respond to you art? My work generally is well received by fellow prisoners. Many seem to have difficulty believing that I actually created what they're seeing, most likely because my style is so different from what they're accustomed to seeing in prison. Most of the work produced in prison naturally leans toward tattoo art, even when the art is not intended for an actual tattoo. I've done my share of tattoo designs over the years - and in fact all of my own tattoos came out of my designs - but even then the style is unusual. My take is that a lot of people tend to like what they think their peers will like, so there is a marked similarity in much of the art produced in prison. Is there a community of creative people inside your prison? In every prison, you will find a community of artistic and creative people, though such communities tend to be small in this environment. At a very basic level there are people who are moved to express themselves creatively and those inclined to express themselves destructively. Prisons by their intrinsic nature tend to foster the latter more than the former. Those who choose to go against the grain and produce meaningful art must be determined enough to overcome some challenges and obstacles. There are always at least a dozen or so men in a prison who are driven and passionate about creating art in spite of the hindrances, lack of opportunity and resources. For some it is a path to liberation, a way of freeing themselves from a criminal past and the resulting confinement – even, for some, when parole is not a possibility. Do you follow the movement known as Prison Art? Not really. I am only peripherally aware that there is such a movement. I think it's great that people out in the greater community are able to view and connect with some of the art that is produced in prison. Hopefully this is being done in a way that is not exploiting the artists. Who buys your work? How do you market it and what do you do with the money? Presumably the people who purchase originals or art prints of my work are people who have a genuine affinity for my work. As for marketing, I don't put a whole lot of energy into promoting my work for sale. I believe that all people, including and perhaps especially artists, have a responsibility to share their God-given gifts with the world. Sharing my work is a spiritual mission for me, so that's the emphasis in how I put energy into making it available to people. As a general rule, I put high resolution images of all my visual art in my online gallery. Anyone can see the body of my work for free, and even zoom in to see details. When an original or art print is bought the proceeds go to supporting the infrastructure that makes it possible to share the work with the public, including costs associated with the online gallery, art materials, paying the person who manages the infrastructure, and that sort of thing. In those rare instances when there is a surplus, any financial returns are put into a trust I have set up for my children and grandchildren. Many of the originals of my paintings are given to members of my family or friends; occasionally I put an original up for sale, and I have been known to accept a commission from time to time. Is art just a way to pass the time, or do you find it therapeutic? Times passes all on its own without any help from me. The difficulty is in finding enough of it to get all the work done that I've taken on. Were I to catch myself doing a painting out of boredom, I would stop immediately and do some yoga. Honestly, I can't remember the last time that happened. Working on visual art or music is a kind of meditation for me, a good practice for staying in the moment. That's a kind of therapy, I suppose. To see more of Bobby’s work, visit his website: http://www.bobbybeausoleil.com/ Read Beausoleil's "Manifesto of an Artist in Prison" to learn more about his views on creating art from behind bars, rehabilitation, transformation, and the power of creativity. Anthony Stechyson Anthony Stechyson works in many aspects of film and television, including commercial and documentary. His background is in theatre, performing arts, and poetry. His special interests include avant-garde cinema, art, and literature. He is currently directing a film about the Canadian cult writer Crad Kilodney. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|