|

0 Comments

A Cold Encounter

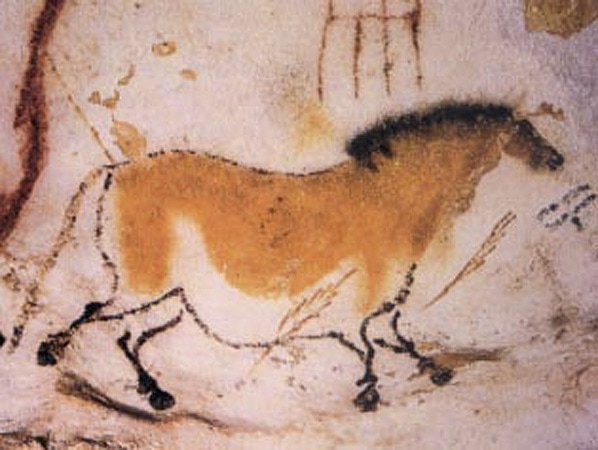

The cold marble curtain cuts cross her face. She looks away, wrapped in stone, no embrace in her eyes, which avert their gaze elsewhere, past me, though I shift to catch her stare. I think some harm or loss troubles her mind, but as I move with eyes prepped to be kind, the windows to her soul shutter out mine. She still looks out, but I can find no line in, to see the person hiding inside. “Why should two, such as we, try and hide? True, we just met, but we share so much. We have loved. We have lost. We both long to touch our lives to another so that we know their heart, and they know the shape of our nose. But you hide, and soon I will walk away from an immortal face designed to play shamelessly reflecting a unique gaze through unique eyes. But this world is a maze and though we should walk together in pairs, we meet lost souls and make our face a wall.” Daniel Chapman Daniel Chapman is a lover of words currently voyaging the seas of cybersecurity - sailing by day and writing by night. He has been known to embark on other crazy endeavours like writing a poem every day for a year. You can follow his progress at www.danielschapman.com. itinerary of a traveler through darkness day one refresh batteries check for matches sunglasses day two now where did i leave that map day three once you get accustomed to the darkness there is just so much light day four breakfast at the black hole lunch at the invisible nebulae dinner with dark matter day five emerge from third world into fourth extend antennae to thunderclouds bring down the rain day six open the soil plant your seeds cover them with earth day seven "and on the 7th day, the dark god rested" William Schmidtkunz William Schmidtkunz is the author of Home, and Other Poems, about life as a carpenter in Alaska. This poem was inspired by the chapbook of art and poetry The Luzajic Variations, a collection of poems by Ekphrastic contributor Bill Waters, after the paintings of Lorette C. Luzajic. There are still a few copies of this limited edition gem- click here to view on Etsy. Ad Mariam She is completed only when I kneel. From the blue alcove she leans over me suspended by the grace of God (or maybe concrete nails), voluptuous in stone, all wind-blown folds and curls. She wants my hand. She’s reaching for it, palms curving like mine, the tender tension bending her fingers, the right extended toward me, then the left directing to the tiled heaven at her back. She’s ample. Fleshy. Skirt hiked up toward her strong thighs—an interrupted motion on her way to wash, or plant, or touch. One shoulder drops, exposed. She wears no bra; her breasts fall full, as subject to the march of time and mothering as mine. Her eyes, however: blank. The Lady has a soul, yet it dies out between her nose and brow. Her figure teems with life, yet she presents as blind. Are we meant not to bond with her? Is she merely a conduit, a bridge that rises on the hour, every hour, to propel us sinful vehicles past her mantilla’d head into the wall where we might be squashed flat but, man, the ride was worth it? I believe her more than infrastructure. She wants me. I, her. And if I stand now, clear the kneeler, clamber Up the stone, I know it will feel warm. Julia Rocchi Julia Rocchi writes prose, poetry, prayers, and picture books. She holds an MA in Writing (Fiction) from Johns Hopkins University. Her work is forthcoming in Mulberry Fork Review, and her poetry has appeared in the anthology Unrequited: Love Letters to Inanimate Objects. Julia lives in Arlington, Virginia, with her husband. Lascaux II. Few galleries are more beautiful. There is a hush, a sense of the sacred. In the dim light the walls shimmer, covered with confident boldness of line, beauty of eye, antler, hoof and horn, curves and bumps and ceiling too masterfully integrated into one fluid flow. 17,000 years ago, in the nearby cave of Lascaux, men and women mixed their colours, prepared smoke free oil, built their scaffolding and, like Michelangelo, covered the walls or lay on their backs and painted the roof, moved by their muse, a deeply human compulsion to not just represent the power of hoof and curve of horn, but to create beauty, to seek meaning, and to reflect the sacred, a sense of something vast beyond themselves of which they were a small, vulnerable but gifted part. I know you, my brothers, my sisters, painting in your cave. Your sensibility is mine. This human finger, touching the keyboard, shaping words into patterns, seeking order and meaning, surely comes from shared desire. Is it really so different that your vision was herds, horns and hooves and the mark of your hands on the wall, whilst mine is songs of the heart, longing for compassion and surrender to love, when we, in vulnerable mortality and common humanity desire the beauty of art and communion beyond self with the mysterious divine. Neil Creighton This poem was first published in The Literary Yard. Neil Creighton is an Australian poet with a passion for social justice and a love of the natural world. Recent publications include "Poetry Quarterly", "Silver Birch Press", "Praxis Online", "South Florida Poetry Journal" and "Verse-Virtual", where he is a contributing editor. His poetry blog iswindofflowers.blogspot.com.au Next Door to the Depot

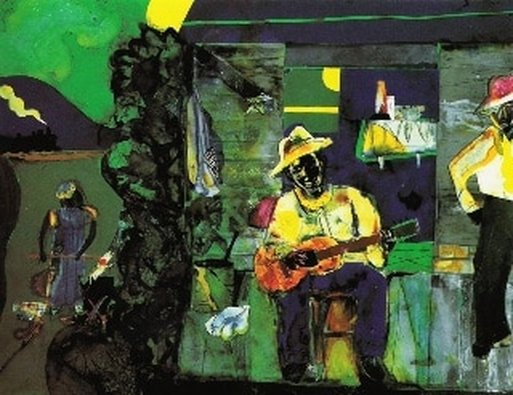

Trains pass in the night wailin’ out the blues, askin’ me, “Hey, loser, what else you gonna lose?” Seems I’m always here glued right to this spot holdin’ onto misery like it’s everything I’ve got. Maybe I’m a fool ignorin’ all those trains. Maybe I should jump one and not come back again. Trains pass in the night wailin’ out the blues, askin’ me, “Hey, loser, what else you gonna lose?” Alarie Tennille Alarie Tennille was born and raised in Portsmouth, Virginia, and graduated from the University of Virginia in the first class admitting women. She became fascinated by fine art at an early age, even though she had to go to the World Book Encyclopedia to find it. Today she visits museums everywhere she travels and spends time at the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, Missouri, where her husband is a volunteer guide. Alarie’s poetry book, Running Counterclockwise, contains many ekphrastic poems. Please visit her at alariepoet.com. On Dali “I myself am surrealism”, he says as the tips of his moustache touch together. The echo inside his diving suit made it difficult to make out his words. His cane, by itself in the corner, diverts traffic. Breton is frowning, hoping this Catalan will not paint the two of them. Puffing on his pipe, deconstructed as no longer a pipe but an image of a pipe, Breton contemplates the compromised position of surrealism. It all comes down to politics, and Dali follows Dalism. He says, “My obsession with Hitler is aesthetic fancy. Look at him there with his braces, saluting swastikas.” He says, “Look at the curve of his back.” Orwell stands across from Breton, his middle-class nose turned up in disgust. The two of them lower their heads and point their curved backs towards the man who stands with his cane and his waistcoat and his ocelot, making faces. Simon J. Ward Simon J Ward is a writer of poetry and short stories. He teaches composition, literature, and creative writing at Anne Arundel Community College, and also works as a Sous Chef in Baltimore. His poetry has appeared in literary magazines in both the US and the UK, and his prose is upcoming in Workers Write! He obtained a Masters in Creative Writing from the University of Glasgow in 2012, and is the founding editor of the Glasgow-based literary anthology ClockWorks. J. Petrinovic, to Her Viewer The following interaction with Gerald Leslie Brockhurst’s Portrait of J. Petrinovic was recorded in the University's art gallery Nov. 13, 20__ Yes, it is me you hear. It happens, rarely, but sometimes. Look at my portrait. Please see me, or at least how Brockhurst, as he had me call him, painted me. Don’t follow your gentleman into the next room. I need you more. Stay. I heard the disdain with which he spoke. It’s how my husband and Brockhurst talked to me. Maybe that’s why you can hear what so many do not. We share circumstances, perhaps? You are his girlfriend? Mistress? Wife? Did he present you those beautiful pearls and the matching teardrop earrings, or did you buy them? They frame your face perfectly, and I hope they memorialize a happy occasion. I purchased these graduated pearl strands from money my husband gave me to help me get over the loss of my daughter at the hand of that low, alleyway doctor to whom he sent me. Do I see sadness in your face? Can I help? In life, I desperately wanted a friend with whom to share my story, trust in her response, and be, in return, her giving mirror. Instead, I am now an unsympathetic figure, my background a few hills and indistinct light, hung here unable to offer or receive comfort. Those who knew me in life are gone, and I am eminently forgettable to the relative few who take more than a moment to glance inside my frame. At least the docents find me useful. A few times each day they gather groups before me, offering the same introduction each time: “With portraiture, the artist paints a story you get to tell about someone you didn’t know.” Then they ask for a story, and the criticism begins. My jaw is too prominent; my blush or lip paint too obvious; my hair too severe, parted on the wrong side with an auburn shade unlikely for my colouring; my look accusing. I am not heroic like the woman seen around the corner on a Jacob Lawrence panel. I am just a stuck-up bitch, one young person said. Can you imagine such a horrid phrase? How can people think they know me like that within seconds? Your clothes, like mine, are fashionable, not flapperish. Do people talk of you as they do me? The nice things said, such as they are, are voiced by children. A particular boy and another girl said I was pretty, but then said no more after their teacher hectored them to explain why. In another group, a few children decided I must be rich, and they would be nice to me so I would buy them lunch, new clothes, sneakers, and maybe even video games. For nearly every adult visitor who comments, I am the stooge they compare to my neighbors on this wall. Many see me lacking in natural graces juxtaposed to the innocence and natural beauty they find to my left in the smaller portraits by Milton Avery of a “Nanny,” and Daniel Huntington’s “Study of a Young Woman.” People’s faces light up with happiness when taking in Robert Henri’s young man, “Johnnie Patton,” to my right. A shadow falls as they shift their glance toward me. It suggests paranoia if I talk of conspiracy. Still, I occasionally wonder if the curators have hung me in some way to make the boy seem more heroic by comparison. He is here courtesy of the family for which this gallery is named. But that is madness, yes? The result of too much time to worry my fate. Brockhurst was celebrated and well compensated for making women glamorous with his brush and oils. His, I suppose, was the luster my husband wished to reflect through this commission. Everyone knew the artist’s history with women. His two wives often modeled for him because, like Edward Hopper’s wife, Jo, they foolishly thought reducing his intimate exposure to other women would keep him from cheating. During my sitting he joked about dabbing some of his wife into my features to keep her off the track. I did not accept or encourage his advances. Do I read in your eyes similar experience? Will you trust that I am not lying? I am not sure my husband did, leading to the argument over money between him and Brockhurst that leaves me—this portrait of me anyway—undated. The omission must imply to many observers I am unfinished … unworthy. Brockhurst would lecture while he painted and speak of how an artist attempts to capture the subject’s mind, brain, and especially her soul on canvas. Could there have been too much of the latter, which has given me this cursed afterlife? Was there too little, which is why nobody sees anything closer to the real me? Was I cursed into this eternal melancholy by his wife? My own husband? Perhaps I lost a competition—one I was most unaware of—with that debauchee, Margaret Campbell, Dutchess of Argyll. Her sitting overlapped mine. Our portraits are similar, although hers is commonly discerned as a finer example of his work. With forever to think, my mind stops, starts, and revolves on the same track like a boardwalk carousel. I am not, as I’d hoped, a figure inspirational and tragic, like the unknown woman of Poe’s “Oval Portrait.” Not a metaphoric expression of tortured artistry like Wilde’s closeted Dorian Gray. Regrettably, my definition has become what I am not—so much moreso than what I once was. Funny, when no guard or visitor obstructs my view, I spend hour after hour staring straight across the gallery at Jean Dubuffet’s mostly golden “Geomancier.” Visitors kindly describe that heavily layered oil abstract. Somehow it comes across as three-dimensional and inspiring of multiple interpretations, while I am two-dimensional and easily dismissed. One day Brockhurst described the book he was reading, Edwin Abbott’s “Flatland,” about a two-dimensional world. Could he somehow have whisked those ideas onto the palette, defining the woman you see here? Some of the women who stand in your place-- Wait. Please don’t leave because he calls. I know what happens if you let him choose your direction for you. I am what happens. I need you. Stay. Kent Oswald This story first appeared in Easy Street Magazine. Kent Oswald’s work has appeared in LA Times Book Reviews, Tennis Industry, Cigar Aficionado, Six Sentences, and elsewhere. He tweets @Ready4Amy and @CupidAlleyChoco Climbers' Light

Honey-mustard alpen-glow Just lapped up By a wolf of evening shadow Hurries our steps Down from summits too long savoured - But while stars open Above wastes of stone The highest snowfield Burns white As Owens Valley sands at noon. Our path shines clear In Climbers' Light. Robert Walton Robert Walton is an experienced writer with several dozen poems published. His novel Dawn Drums was awarded first place in the 2014 Arizona Authors Association’s literary contest and also won the 2014 Tony Hillerman Best Fiction Award. He is a retired teacher and a life-long rock climber. Matisse: the Terrace St. Tropez

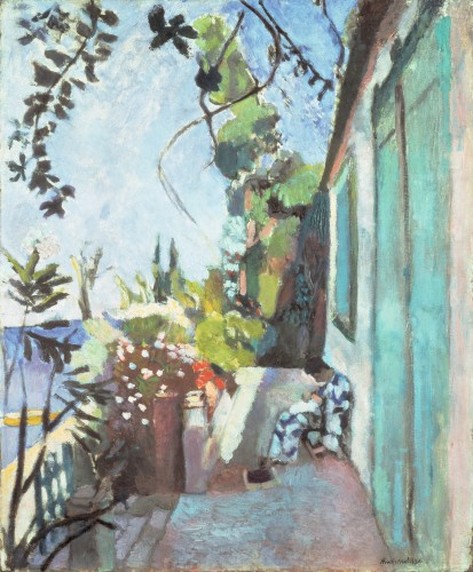

Here in Saint Tropez, colours melt in the Mediterranean sun. Frontiers vanish and I am left with an impression, as vague and wondrous as the the touch of an ancient memory, half forgotten, of sea and sand and indiscriminate joy. Here on my terrace, the shadings shift so swiftly with the slant of light, it is as if time itself has had a hand in mixing my poor palette. I spend my days in gifted sight and paint the blur of hue and time, as freely as the gulls will skate upon the vast horizon of endless sea and endless sky. Steve Deutsch Steve Deutsch, a semi-retired practitioner of the fluid mechanics of mechanical hearts and heart valves, lives with his wife Karen--a visual artist, in State College, PA. Steve writes poetry, short fiction and the blog: [email protected]. His most recent publications have been in Eclectica Magazine, The Ekphrastic Review, New Verse News, Silver Birch Press, Misfit Magazine and One-sentence poems. As an adult, Steve had the good fortune to sit in on two poetry classes taught by first class poets and teachers. He has been writing poetry ever since. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|