|

Impasse The dress Marcia gave Linda hangs in the balance, stranded in the middle of Marcia and Linda, Marcia having long retreated, Linda finally setting it down on this long board of shadow and light. Everything is suspended between Marcia and Linda : the muted ends of the ironing board, the iron versus the plug, the rumpled acquiescence of the dress with its hint of a grandma’s apron before the upright iron’s dead weight. One day, Linda will answer the call of the iron’s handle, swinging the pensive face into action as if moved by sudden resolve to rescue a wrinkled cry, Marcia’s yellows and greens rallying beneath the rhythm of Linda’s elbow, the ageless, ordinary grace of countless elbows before. Only then can the skirmish of necklines with the blunt-haired woman on the wall and the ragged trees mend with the glorious truth that nobody wants this dress. Janis Greve Janis Greve teaches literature at UMass Amherst, specializing in autobiography, disability studies, and service-learning. She has previously published in such places as The Florida Review, North American Review, The Berkshire Review, and more.

0 Comments

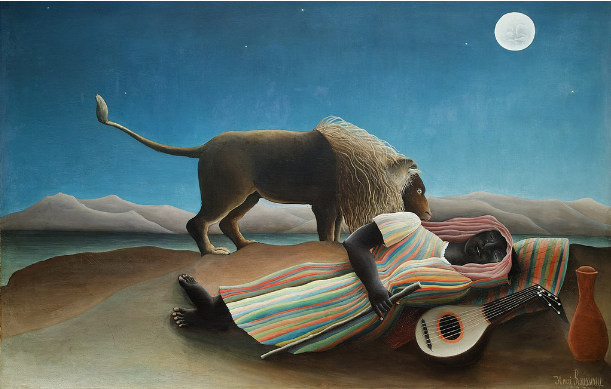

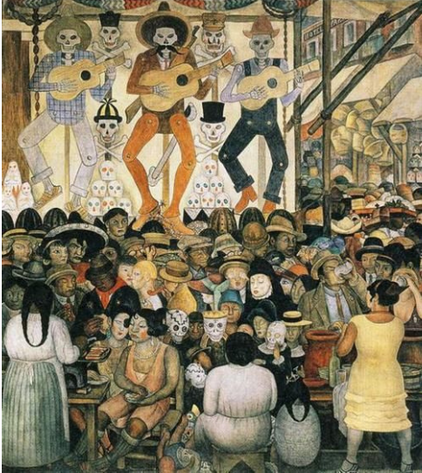

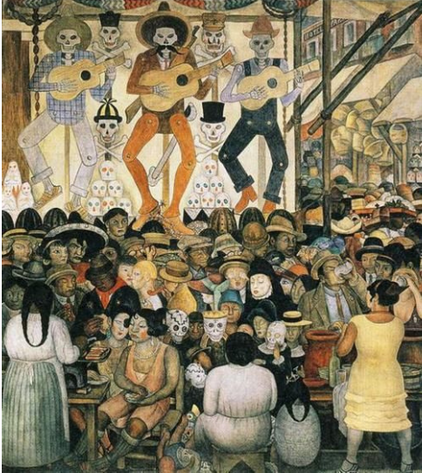

The Jewel Box In the before days, Gemma’s furtive pleasure was the view out her windows, across the sweep of late summer cornstalks that drew the lines of sight along and then past the creek, forging up the lazy incline of the dusk-blue mountains. She had no desire to leave the confines of her interiors to explore the stark peaks and shadowed valleys, despite ― or because of ― their seductive whispers of beauty and transformation. Better to stay away from the unknown crevices and frightening heights. The possibility of unexplored regions. The fear of no return. The damp terror of wildness. In the beginning days, rumors of the plague had filtered through to Gemma but only in the way that knowledge from a great distance might reach the domain of the uncurious. A shooting star; a foreign tongue; a wasp's sting; the frisson of desire. The roof peak: the thick heavy doors, front and back; the bolted casements: these were the custodians of Gemma’s world. The stillness, the precision, would not be defiled by guests, nor mail delivery, nor telephones, televisions, spurious merchants. Nor men. Never men. With their dirty hands, their mud-crusted boots, their fingerprints on the sanitized surfaces of her unsullied world. The plague seeped like flood waters from cities to suburbs to towns to villages to hamlets to abandoned shacks and animal sheds, uncultivated plains and valleys. A few farmhouses remained, held fast by elderly couples and their mangy dogs, hollowed-out cattle, feral cats. Each day, Gemma shined every facet of the jewel box she called home, as she had for decades: kept the curtains crisp, the cushions plump, the ceilings and crevices free of spider webs and insect trails. She did not collect knick-knacks, hung no photographs of deceased relatives, no clumsy reproductions of fine artworks. The surfaces throughout the rooms of her home were ― like her mind, her body, her inner life ― unadorned. And flawless. However, as perhaps you and I may have predicted, there came an afternoon, deep into the plague years, that Gemma’s polished reality showed signs of tarnish. As weeks and weeks were followed by many more weeks of soothing sameness, portents of slight but perceptible change began to appear. Take note of the gap in the molding between ceiling and wall. Tiny, at first; thin as a silken thread, incidental as a stray pencil stroke; but the next day it was thicker, the width of two pencil strokes; the wood ends pulling away from each other, as though the attraction that once held them close had decayed. Worse: across the room, the hanging wire that anchored the large oak-framed mirror, a decorative but functional object that Gemma tolerated, had shifted a quarter inch to the right. To her horror, this misalignment prompted a visual off-kilter echo, disdaining the perfect geometry of the mantel and the unused fireplace. Gemma, on this occasion that had become unexpectedly distressing, was wearing, as was her habit, one of several outfits she owned that highlighted the spectacular hand-painted wallpaper. The richly saturated garnet hue of her dress picked out and magnified the flashes of a ruby-coloured tail feather in the plumage of the pheasants repeated throughout the vibrant motif. But now it's slipping away and it's more than she can bear: the purity, the hard-won perfection and even worse, the day-to-day struggle to stave off any hint of fallibility in her singular aesthetic victory. The tilted mirror; the flaws in the ceiling molding; the dimmed-down glow of her brilliant achievement. Her lovely outfit brings no joy to Gemma. The plague has come to her; and even in this faultless shelter, she must open the door to pain, sorrow, lust, derangement, and death. Life and its beauty lie not in containment or control, but in opening up and letting go. Susan T. Landry Susan T. Landry is a semi-retired medical manuscript and creative writing editor. She writes for pleasure, and has published poetry, fiction, and memoir. She lives in Maine, USA, reads voraciously, and travels whenever possible. Brigid Kennedy is a contemporary American artist, born and raised in Western New York. Kennedy creates work across multiple disciplines including painting, sculpture and drawing. Her recent paintings examine today’s social and cultural challenges, memory and the visual complexity of daily life. Kennedy received her Bachelors of Arts degree in Philosophy from the University of Toronto, her Bachelors of Fine Arts degree from the State University of New York at Buffalo, and her Master of Fine Arts degree in Sculpture from Yale University School of Art. Having Been Born, Having Been Raised Purified by an authentic filter orange for the fake names we say or blue for clean slate the ideal slices through us embedded with shock safe vessel for turning a thing over like a rock like a shangri-la that we could still be surprised by the amber inventory four o’clocks in the floral clock or daturas at midnight sometimes we leave a dream before it’s done with us sometimes we hold on to the wrong thing dumb to our instincts one day wake up, feeling what a stone feels leaving the hand Julie Choffel Julie Choffel is the author of The Hello Delay (Fordham UP) and most recently the chapbook The Inevitable Return of What We Do Not Love (Finishing Line Press). Born and raised in Austin, TX, she now lives near Hartford, teaches at the University of Connecticut, and dreams about the desert. To Claude Monet Regarding the Water Lilies I am grateful. For me, the water lilies and your story unleashed an energy that washed over me, pushing me forward to leave behind fear and doubt. For you, 30 years and 250 paintings: water lilies in every season, every light, smear of mauve brings twilight shadow, blush of pink captures sunset, sunrise - a stroke of yellow fresh as cream in the morning, afternoon sun casts its web of light, green lily pads frame gypsy clouds traveling both sky and water, ferns bow to the beauty, willows weep, bamboo reaches to sky whispering alleluia. I stood in museums and in Giverny before the altar of the bridge, the sacrament of lily pads. You believed, planted, tended, painted, shared their beauty for all time. So who am I to not believe? Words are strokes on paper, to be dreamed and humbly offered. From you I learned creating is love. Mary Padgen Michna Mary Padgen Michna is retired after 15 years as a journalist, 15 years as a copywriter, and a very satisfying nine years as development director and fundraiser for a free clinic. After retirement, she and a writing friend started a group for sharing, writing, and reading. Her poetry has received an honourable mention from The Franciscan Spirituality Center in LaCrosse, Wis. Another received an honourable mention from the 2022 Passager contest. The Hummingbird and Rembrandt’s Saul A favour pulls me from my pondering of Saul, of Samuel’s scroll, and of the Dutchman’s tortured king with drastic eye, precarious crown perched on a bloated, bandaged mind. My task is not to find a wayward ass but pen three dozen wily fowl of varied breed and skittishness, tight phalanxed ducks and half-grown hens that scatter to the poison ivy thickets at the run’s far edge. Exasperated, I retreat back to my friend’s garage to get the freeze-dried worms he promised would help lure the birds behind wire gates that sometimes keep them safe from foxes, skunks, raccoons, coyotes, other nighttime hunters hungry for an easy meal. But as I search the package out I hear a whir and pop and spy a hummingbird beating between the roof and raised garage bay door. I try to shoo it lightward with a broom and stick, but it, exhausted, lands just out of reach atop the squat rack farthest from the doors and browning sun. The cats that Davey said have brought home headless squirrels hop on the lower bars and eye the cornered bird. Perhaps a scholar cannot help but see his studies everywhere, or maybe they and life do mutually illuminate, but as I try to help that bird escape I see it beating in the turbaned skull of desperate Saul, relentless hum, constricted space, a tiny skeleton convulsed again, again— the overwhelming urge to fly from terrors closing in, a giant taunting him and Samuel’s stern rebuke, an evil spirit circling his soul, and here within his very court a shadowed handsome boy whose songs not long ago could shepherd him to light but who now plucks a moan with each silk garrote string. Steven Knepper Steven Knepper teaches in the Department of English, Rhetoric, and Humanistic Studies at Virginia Military Institute. His poems have appeared in SLANT, The Rappahannock Review, The American Journal of Poetry, Pennsylvania English, Floyd County Moonshine, and other journals. The City Starting at the border of that thousand-piece puzzle under the blue light of sky, I stand on the balcony with the turbaned man in brown and the red-scarved woman, squint my eyes at her brilliant apparel reflected in fiery windows in brick walls painted with sunbursts, dip my hand in red dye and press it to the alley wall as the young boy sprints around the narrow corner play chess with the men on a bench outside the tailor’s shop. Then I examine the jigsaw pieces, turning and trying, until each building, each room, each corridor, each alley, each courtyard eases into the only place it will fit. Andrea Jones Walker This poem was inspired by Steve McCurry's photograph, The Blue City, Rajasthan, India. View it here. Andrea Jones Walker is a Florida native who loves the beach. A retired English teacher and lover of words and art, she's had poems published in several journals and co-edits panoplyzine. She's published four books, and her first poetry collection Altars of Wonder: Poetry and Prose is forthcoming. Judging this unique competition was unalloyed pleasure. It was like standing at the intersection of three different art-forms and watching a fantastic carnival parade by - and sometimes being swept along with it. Perhaps because of the inherent challenge of juggling poetry, music and fine art all at once (in a kind of double- or triple-ekphrasis), all the submitted works were imaginative, sophisticated and strange. Unlike many competitions, there were simply no "bad" entries (whatever that means): I enjoyed every piece, all the weird and wonderful, poignant and funny, tragic and comic, grotesque and beautiful approaches on offer. It was incredibly hard to choose a "winner" from this poetic carnivalesque, and I want to thank everyone who entered for a wonderful entertainment. Jonathan Taylor http://jonathanptaylor.co.uk ** Dear Readers and Writers, A giant thank-you to Dr. Jonathan Taylor for his time and expertise judging this contest. Jonathan is a tough act to follow- his music-themed short stories and poetry are highly acclaimed. But we received so many amazing entries! Thank you to each and every one of you who took inspiration from the music themed artworks we showed you, and created something beautiful and important. Your poetry and stories were truly marvellous. The winner and the selected works to be published were chosen from a document with no author names or bios. It was surprising that from such a vibrant collection of diverse works we had several lucky authors with double or even triple placements in the finals. A big congrats to our winner, our finalists, and every single person who participated. Please spread the word about ekphrasis and The Ekphrastic Review, and help get more reader eyes on our writers, past, present and future. If you can share this or any post on your social media pages, we would be very grateful! Lorette Without further ado, our winner and finalists: First Place Fate, by R. Hamilton Finalists, in Alphabetical Order by Author Exceptional Lion, by Lizzie Ballagher Reef, by Lizzie Ballagher Leviathon Love Song, by Jude Luttrell Bradley Silent Night, by Dorothy Burrows Almeria, by Kate Copeland Calling on All Dead, by Kate Copeland The Harp, 1993, by Kate Copeland Three Women Playing Music, by Katsushika Oi, by Jane Forward Threnody for My Dead Violin Teacher, by Kimberly Hall Gospel Song, by R. Hamilton Some Klicks East of Budapesht, a Café, by R. Hamilton A Little Night Music, by Sue Mackrell The Gypsy Sleeps, by Mary McCarthy Greek Mythology Meets Modern Pathology, by Linda McQuarrie-Bowerman Taking Off, by Bayveen O'Connell Flashback, by Shaun R. Pankoski Sarabande, by F.F. Teague Communities of Loss, by Julene Waffle The Banjo Lesson, by Kate Young Jazz Singer, by Kate Young Contest Winner!!! Fate, by R. Hamilton Fate That August afternoon, Zacarias plays for his maestra guitarra — Madam Izar —a new song he has written that he feels may be a little sad but hopes is not so sad that the village girls who gather to gossip after church (especially the pretty Élina) will no longer flirt with him, leaving him no one to escort home or to make jokes with before going alone to his own house where he lives in reluctant solitude. When he gets to the chorus, though, he notices a senhora dozing, loose in her chair like she is young again, dreaming (he imagines) of her childhood in the Pyrenees before she was forced to flee across the Cantabrian mountains by herself after her family fell victim to Franco’s retaliation against Basque nacionalistas. When he notices her leg twitch, it leads him to believe his theory correct, so he plays on for her, just her, softly, hoping it is his lullaby helping her sleep rather than just the wine and hot weather. R. Hamilton R Hamilton (they/them) is returning to poetry as a means of filling the vacuum left after a fifty-year career backstage in the performing arts, a retirement handily but unexpectedly coincident with the pandemic. Since then, Hamilton’s work has been/will be presented by Boats Against the Current, Caesura, Dollar Store, Ekphrastic Review, Intangible, and Nightingale & Sparrow, among others. Congratulations to all of the writers below, our finalists, whose work was selected for publication. (In alphabetical order, by author.) Exceptional Lion Do you dream, pilgrim, of the lovers left behind-- those you beguiled with your mandolin? Is it wise to travel the thirsty desert with a single water-pot—and quite alone? Or have you drunk deep of mandragora and drift now to another shore where climes are kind, where you need no wooden stave to fend off beasts of prey? My gypsy friend, I think you do not know: this lion’s immortal, exceptional. He’s the one Androcles rescued centuries ago—from whose paw drew out a savage blackthorn. Soft-muzzled, inquisitive, he’s the one who then refused to fall on Christians thrown to him in Circus Maximus, but hunkered down on haunches, licked his tender, wounded paw, grinned gleefully / playfully at the Christians—despite avid Romans’ blood-lust roar. Camping under a ripened moon, and under stars, you’ve no idea how blessed you are, traveller, that it’s Androcles’ holy lion who found you, who watches over you until blue dawn. Strange how your broken dreams, your lonely music, have drawn again the cruel thorn from this old lion. Lizzie Ballagher In 2022, Ballagher was chosen as winner in Poetry on the Lake's formal category with a pantoum entitled ‘Across the Barle’. Her work has appeared in print and online on both sides of the Atlantic; it has also been presented in podcasts on Poetry Worth Hearing (Anchor fm). Several of her poems in the last two decades have, too, been set to music. Contributing regularly to Southeast Walker Magazine, she lives in the UK, writing a blog at https://lizzieballagherpoetry.wordpress.com/. Reef narrowing chasm-- kelp caught in cornflower currents sea-glass harmonics Lizzie Ballagher In 2022, Ballagher was chosen as winner in Poetry on the Lake's formal category with a pantoum entitled ‘Across the Barle’. Her work has appeared in print and online on both sides of the Atlantic; it has also been presented in podcasts on Poetry Worth Hearing (Anchor fm). Several of her poems in the last two decades have, too, been set to music. Contributing regularly to Southeast Walker Magazine, she lives in the UK, writing a blog at https://lizzieballagherpoetry.wordpress.com/. Leviathan Love Song My favourite love song is the one you wrote about my sea blue eyes, in the antediluvian days before Eden. world of two topographies: One you. One me. Awakening in those briny ancient depths after epochs of deep-sea silence, you yawned, opening wide your titanic mouth, in a groggy, foggy gesture I took the wrong way. From the distance of my solitary widow’s walk, I mistook your gaping watery maw for an invitation to take refuge in that fleshy grotto, to lose myself in the depths of you. Creature without fear, I dove headfirst from my yearning perch, swiftly sinking beneath your glistening white wake. You rewarded my bravery with a serpent song. Building slowly like a ballad it gradually uncoiled to reveal a thrashing hard rock hook: YOUR EYES! YOUR EYES! YOUR EYES! The deafening song stripped me bare of fear and loathing, clothes and hair--- then spewed me from your bored belly to gritty shore. Naked. Broken. Bewildered. Reborn. Jude Luttrell Bradley Jude is a Pushcart-nominated writer whose work has appeared on National Public Radio and in assorted literary journals and magazines including The Ekphrastic Review, Tupelo Press, Thimble, Moon Love, and Oberon. Her poem“Had” was selected for Atlanta Review 2022 International Poetry Competition Merit award. “Beasts of No Nation” earned Honorable Mention in the Oberon poetry magazine 2022 competition. Jude’s work re-envisions history, classical literature, and reflects on life in an ever-shrinking, ever-expanding pandemic world. Jude is the Reverend Al Green’s biggest fan. Silent Night A thunder moon; the hot lash of her tongue stalks his loneliness through this cold night in this treeless land of sand and salt pans. Here, he must ache, haunted by surly beasts who prowl through his wine-drenched hours under stars that flicker fake light on his past. He stirs, shivers, stills. He mutters, sensing harsh grit clawing at his feet. His heels shift sinking every grain of hope. While he dreams, his half-gripped staff strikes out at empty air. See how he mocks his lute with ghost-plucks as some random lion mauls his tangled heart. Dorothy Burrows Based in the United Kingdom, Dorothy Burrows enjoys writing poems, flash fiction and short plays. Her writing has been published in various journals and webzines including The Ekphrastic Review, The Alchemy Spoon, Spelt, Dust Poetry Magazine and Wales Haiku Journal. In her youth, she attempted to play the piano. Almería In the house of the guitar players, I learned to sing again. To dance to waves, indalos…my orange space I changed for white silks, it's an All Andalus State of Mind, this Jaleo place of mind, where bliss alternates between wooden boards and shameless arms. Is that good… should I halloo? In the shade of the guitar players, I learned to free again. To curve my body to light, close doors to dark hallways…enter living rooms where beats flirt me, commotional force, my dolphin legs, where signboards alternate between war and mosaics, among tongues and tunes. In the caves of Almería, I learned to write again. To read the troubadours, the unspoilt dunes…a red-sand space I’ll never change, winter blue-green crashing, where I went to see the castle, songs started, and I took pictures of time. Who will remember this…remember me? In the shade of Almería, I learned to fall again. To dance to gitanos, royal poets…I shared my ice-cream and drank vermouth, danced and danced the Sunday long, longing, for my arms around your waist, bronzed. Time shouts ever down the caves. Jaleo stays a never broken chain. Kate Copeland Kate Copeland started absorbing stories ever since a little lass. Her love for words led her to teaching & translating; her love for art & water to poetry…please find her pieces @ The Ekphrastic Review (incl. Podcast & translations), First Lit. Review-East, Wildfire Words, GrandLittleThings, The Metaworker, The Weekly/Five South, New Feathers a.o. Her recent Insta reads: https://www.instagram.com/kate.copeland.poems/ Over the years, she assisted in literary festivals and Breathe-Read-Write workshops. More workshops to follow! Kate was born @ a harbour city and adores housesitting @ the world. Calling on all dead Mira los muertos Get out Salga Best dress and Ropa linda y Sugar skull, orange Calavera de azúcar, naranja Chrysanthemums Los Crisantemos Get out Salga Frida’s blues and De la Frida’s azul y Wear your cloak, a golden Lleva tu rebozo, una Guitar Guitarra dorada Get there Llega And braid your braids Y trenza tus trenzas Fill the market, salute Llena la plaza, saluda With cocoa Con chilate Salud, dinero y amor Salud, dinero y amor Get up Levantate And serenade your nan Y canta a tu nona Our dog Xólotl, recall Nuestro Xólotl, recuerda Their dreams Sus sueños Get up Levantate To dance A bailar The Jarabe, high La Jarabe, altos Hats to honour Sombreros para honrar The two truly dead days Los dos veraz días muertos Get through Pasa The past Más allá Doorway, like Por la puerta, igual The last November Por algún noviembre Kate Copeland Kate Copeland started absorbing stories ever since a little lass. Her love for words led her to teaching & translating; her love for art & water to poetry…please find her pieces @ The Ekphrastic Review (incl. Podcast & translations), First Lit. Review-East, Wildfire Words, GrandLittleThings, The Metaworker, The Weekly/Five South, New Feathers a.o. Her recent Insta reads: https://www.instagram.com/kate.copeland.poems/ Over the years, she assisted in literary festivals and Breathe-Read-Write workshops. More workshops to follow! Kate was born @ a harbour city and adores housesitting @ the world. The Harp, 1993 Lift every voice and sing Till earth and heaven ring - James Weldon Johnson Clannad’s Celtics made me giggle, but you held me hand and introduced me, to concert halls, all royal and all, a piano and a harp, while I laughed at first, looked for my lipgloss, loved you at the end, at coda, and you held me to tell too, about the gigs I felt, devoured, in a lifetime, about Shaw’s Cali Soul, that holds my melancholy forever, for ages, the stages, they held canyons, where neighbours shared the cats and cabins, the guitars, high as listening skies, and maybe I should witter less, yet you kept such gruffed mountain views, the slowhands got me on my knees, made me fall, with you, him, players, with tastes and thirst, and so will I forever sing, string, along a breakfast song, past an emptiness on my bed, undress me, whisper or cry, till heart meets atlas, as I waited till we drove ‘round an island and dove into blue, you do something to me, and so, whether West streets or port towns, my distance started while you held my hand, with rooms on fire, but I never laughed like before, when Clannad staged the harp. Kate Copeland Kate Copeland started absorbing stories ever since a little lass. Her love for words led her to teaching & translating; her love for art & water to poetry…please find her pieces @ The Ekphrastic Review (incl. Podcast & translations), First Lit. Review-East, Wildfire Words, GrandLittleThings, The Metaworker, The Weekly/Five South, New Feathers a.o. Her recent Insta reads: https://www.instagram.com/kate.copeland.poems/ Over the years, she assisted in literary festivals and Breathe-Read-Write workshops. More workshops to follow! Kate was born @ a harbour city and adores housesitting @ the world. Three Women Playing Music, by Katsushika Oi Silk kimono and uchikake rustle and billow as the women settle onto the floor. It is winter, the padded layers make cozy nests for the musicians. Perfectly coiffed hair, painstakingly combed and waxed into shape, adorned with bamboo ornaments and silk flowers, do not cover shell pink ears. Heads tilt and bend, so as best to hear the gentle strains of koto zither, sanshin lute, and upright kokyu whose bow draws slowly downward, coaxing out a bird-like voice. The delicate strains of the instruments can be heard only by them, the artistry of their music drowned to onlookers by the crescendo-decrescendo of father’s great wave off Kanagawa. Jane Forward Jane Forward loves diving down the rabbit holes of research she enjoys when preparing to write an ekphrastic piece. Jane was delighted to learn the tantalizing tidbit that Katsushika Oi’s father painted Thirty-six Views of Mt Fuji, including The Great Wave off Kanagawa, a painting tucked away in her folder for yet-to-be-written ekphrastic flash fiction. Her attempts at this art form can be found on her website: jkforward.com Threnody for My Dead Violin Teacher Recommended listening: Adagio for Strings (1936) by Samuel Barber; Élégie for Solo Violin/Viola (1944) by Igor Stravinsky; Threnody to Toki, for String Orchestra and Piano (1980) by Takashi Yoshimatsu You died just after the turn of the year. That’s not the hard part of this. The hard part is finding the right colours. The right tones, textures. There is so much to express, and I don’t want my memories to all blend into this sickly haze of green – slippery, like my contact point when I don’t use enough rosin, like the smell of grass beneath my feet as I wonder how much time is left before the evening storm. I roll my shoulders and my wrists, and I remember how you would scold me for my rounded posture. My pigeon toes. I remember how you would sigh that particular sigh, and my heart would drop into my stomach. I soften my tone. Widen my vibrato. I pay attention to the weight in my fingers, let the music swell and release, like a good cry. Like the sky after rain. I remember the hymns you would hum beneath your breath, and time the shift of my left hand just so my fingers glide along the overtones and the natural harmonic sings. I remember to breathe, so that the phrase lasts as long as I can bear it. As the final note rings in the quiet, I wait for the echo, but – but you died just after the turn of the year. There will be no answer. Only the green root, diminished. Only memory. Tension without resolution. An unstable cadence in unsteady hands. Kimberly Hall Kimberly Hall (she/her) is a queer and neurodivergent poet and writer. She received her master's degree in behavioral science from the University of Houston-Clear Lake. Her poetry and prose can be found in online publications such as First Flight, Sappho's Torque, and Equinox, as well as in several ekphrastic poetry anthologies and an upcoming anthology from Mutabilis Press. She still gets the idiomatic butterflies whenever anyone mentions these things where she can hear them. Gospel Song In a preferred and alternate universe, Moshe returned from the Sinai heights holding aloft clunky stone tablets clarifying the Cycle of Fifths, the differences between Aeolian/Mixolydian/etc. modes, and how best to avoid an arbitrary use of the C clef. Also included were a few forebodingly proscriptive admonitions concerning, for example, parallel octaves, stupefying consonance, and polka arrangements of Pink Floyd. Sadly, in this — our — world, such wisdom was lost to us forever by the regrettable accident of its being unnoticed under some old rags in the raided ark of Indiana Jones because its curators were distracted by Offenbach on the radio. R. Hamilton R Hamilton (they/them) is returning to poetry as a means of filling the vacuum left after a fifty-year career backstage in the performing arts, a retirement handily but unexpectedly coincident with the pandemic. Since then, Hamilton’s work has been/will be presented by Boats Against the Current, Caesura, Dollar Store, The Ekphrastic Review, Intangible, and Nightingale & Sparrow, among others. Some Klicks East of Budapesht, a Cafe Some klicks east of Budapesht, a cafe carved from old rubble can sometimes be noticed by passersby in the dusk when the light is brittle enough and sharp, its location a mutable thing depending primarily on the traveler’s grasp of sobriety, their willingness to toss a forint or two into the cup for the musicians, and how broken are their hearts. Joska performs Brahms’ Hungarian Dance #5 on his melancholy guitar slowly in a pale key so well that the ghosts of war and plague alike are prompted to push aside their chairs for the czárdás, their feet gliding slightly above the floor and flawless, all but ignored by Réka and Csilla who use bits of sausages on forks as puppets to argue about the decline of the carnivalesque in cabaret over their goulash and beer. Meanwhile, on his drum, Oszkár plays histories that we deny over and over again, thrumming the way this great Plain of Pannonia has been overrun repeatedly, unrelievedly by Mongol horde, Ottoman empire, Axis sympathizer, and Fascism, Fascism, and still more Fascism; Whereas the songs of loss that as birdlings fly away into the evening from Zindel’s concertina will stay with his audience forever, like first love: haunting us over and over again all over and over again. Luca’s red dress warms the scene like a small, local, vital sun orbited by three moons in perfect gravitational symmetry, balancing each other seamlessly as she sings so softly, so gently lyrics using unknown words. They all side-eye the sounds of rockets combatting in the Ukraine sky over the near mountains, and play louder in the hope that by doing so they can send the missiles back from whence they launched; a noble goal to which they seem most dedicated. Moved, I reach into my bag for my wallet to offer them a monetary token of my appreciation, but when I look up, they are as gone as yesterday; leaving behind only a faint trace of melody swiftly fading into fable while the horizon flares with the false dawn of disharmony burning bright. So I make myself comfortable to await the next show. R. Hamilton R Hamilton (they/them) is returning to poetry as a means of filling the vacuum left after a fifty-year career backstage in the performing arts, a retirement handily but unexpectedly coincident with the pandemic. Since then, Hamilton’s work has been/will be presented by Boats Against the Current, Caesura, Dollar Store, Ekphrastic Review, Intangible, and Nightingale & Sparrow, among others. A Little Night Music Once upon a time she was told don’t. But she did, this girl and her doppelganger doll with spectral hair, curious and curiouser about forbidden rooms in a corridor carpeted in blood-red, where a sunflower lays its heavy head, tendrils writhing. She swoons. Petals hang from her hand as she is caught in a Shining vortex of energy that rips her lace to ribbons. Behind her a door opens a piano plays Eine Kleine Nachtmusik. Adagio Sue Mackrell Sue Mackrell lives in Leicestershire, UK. She has an MA in Creative Writing from Loughborough University. Retirement from teaching and facilitating Creative Writing workshops gives her more time to write. Her poems have been published several times in The Ekphrastic Review and Agenda, also recently in Bloody Amazing (Dragon Yaffle) Diversifly (Fair Acre Press) Whirlagust III (Yaffle) and online in Words for the Wild. The Gypsy Sleeps In a desert landscape under an almost starless sky between the lion and the mandolin Her black skin scarless without the lines of grief and worry her hair dressed with red ochre and combed straight without knot or tangle simple as the lines of her long striped gown She smiles in her sleep while the lion wakes his wild heat banked against her stillness his hunger quieted even while her mandolin rests silent at her side the memory of its magical vibration holds them close breath to breath she smiles and he leans in to listen to the music of her dreams Mary McCarthy Mary McCarthy is a retired Registered Nurse who has always been a writer. Her work appears in many anthologies and journals, including The Ekphrastic World, edited by Lorette C. Luzajic, The Plague Papers, edited by Robbi Nester, and recent issues of Verse Virtual. 3rd Wednesday, Blue Heron Review. Earth’s Daughters, Gyroscope, and Caustic Frolic. She has been a Pushcart and Best of the Net nominee. Greek Mythology Meets Modern Pathology Orpheus, you didn’t keep your word and like Lot's wife, you messed with gods and paid the price, Eurydice lost to you forever. Perfect beauty and divine music did not save you from the consequences of your actions. And what of us who are like white bread to your brioche? We stand no chance against our own weaknesses. Every day we hear the stories of miscalculation, the down-right stupid and the dead and dying, smaller articles on the bottom right-hand corner of page 24 reserved for those of us anonymously unimportant and the larger, in-your-face lamentations for the rich, the famous and the infamous and the families of the rich, the famous and the infamous who do not contribute more to this mortal world. Our human priorities are skewed. We’ve forgotten who makes the world go round. The checkout chick/guy and the night packer and the garbage collector and the cleaner and the waiter and the shop assistant and the miner down a dark, black hole and the maid who ‘yes sir/yes ma'am's’ all day long and the plumber scraping out slime from pipes and the young au pair who has to listen to the rich kid’s constant squealing, all for a room (cupboard), next-to-no pay and the husband’s hand crawling up her dress and the receptionist condemned to smile at everyone until her mouth’s in rictus and the gardener on arthritic knees pulling out weeds and the baker crawling out of bed at 1 am and the teacher now expected to be educator/mum/dad/counsellor/juvenile offender warden, and when I think way back to when I was a kid, the dunnyman, carrying the overflowing outdoor toilet cans heaved up on his shoulder vomiting all the way back to his truck. Orpheus, I think you got off lightly. Linda McQuarrie-Bowerman Linda lives in Lake Tabourie, NSW, by the sea. In this beautiful environment, she writes poetry and has recently dabbled in flash fiction. Linda is completing her Degree in Creative Writing at Curtin University and enjoys seeing her work published in various literary spaces. She is a recent Pushcart Nominee thanks to the Ekphrastic Review. Taking Off We are not swans. We do not mate for life or share the same plumage. We do not inhabit sleepy canal banks or glide on still lakes flanked by mountains that mimic the curves of our backs as we dip down to feed. Our necks do not intertwine to make Valentine hearts. We do not make eggs; we break them. We hiss. We flap and drive each other further away in the wake. We pluck at the feathers of our good times and let the wind take them. We spread our spans wide for one last embrace and all we feel are the brittle bones of who we were when we tried to fly. Bayveen O'Connell Bayveen O'Connell is an Irish writer whose flash fiction has been nominated for the Pushcart Prize and for Best Microfiction. Her words have appeared or are forthcoming in Brilliant Flash Fiction, Janus Literary, Splonk, MacQueens Quinterly, The Ekphrastic Review, The Forge, Fractured Lit, and others. She's inspired by travel, folklore, history, myth, music, and art. Flashback Nineteen seventy nine. Disco was almost dead. But not at The Stage Door. Not yet. Donna would moan on a Saturday night while the smoke machine churned and the mirrored ball turned reflecting our faces, sweating and glittery, bright eyes wide and shining from cocaine and poppers and pure adrenaline. When The Village People sang YMCA, we sang right along with them, dancing the alphabet. Sylvester made us feel mighty real. We were bad girls and macho men, beep beeping, toot tooting our way to the eighties, when everyone started to die. Shaun R. Pankoski Shaun R. Pankoski lives in Volcano on the Island of Hawai'i with her cat, Kiko and more coqui frogs than she cares to mention. Her two most treasured possessions are handwritten thank you notes from Lois-Ann Yamanaka and the late Barry Lopez. She has kicked cancer's ass (twice) and makes a mean corn chowder. Sarabande She is playing Debussy as marked in his note, with a solemn and slow élégance; it resounds in her clothing, her fashionable coat, through this sombre and chic courtship dance. It should be like a portrait, Debussy had said – an old portrait, a Louvre display; she is subtle in colours, her lips barely red and her skin tone a soft gold-and-grey. And her lover keeps painting, perhaps with a smile, maybe more, as the sarabande swells, and the chords are progressing; she sits with such style, as she saunters through all parallels. F.F. Teague F.F. Teague (Fliss) is a copyeditor/copywriter by day and a poet/composer come nightfall. She lives in Pittville, a suburb of Cheltenham (UK). Her poetry features regularly in the Spotlight of The HyperTexts; she has also been published by The Mighty, Snakeskin, The Ekphrastic Review, The Dirigible Balloon, Pulsebeat, Lighten Up Online, and a local Morris dancing group. Other interests include art, film, and photography. Communities of Loss His Hohner hunches in his hands like an old cat curled in his lap. When the bus breaks loose on the corner and commuters pour out like ants freed from a child’s glass farm, he rises as if ceremony stands at his heels. He lifts his leg to lean on the chair he uses between buses on hot days, long days, and begins to pull and press and pump his way through a few happy polkas. Strangers pass without change in his case or nods in his direction, but when he plays a tune his father taught him about the old country, that hums a longing note under peaky memories of his mother after typhoid and his sister whose love died in the trenches, It is then that people stop, then that they listen, and then that the change clinks in the old man's accordion case echoing all their communities of loss. Julene Waffle Julene Waffle graduated from Hartwick College and Binghamton University. She is a rural public high school English teacher, an entrepreneur, a nature lover, wife, and mother of three boys, two dogs, three cats, and a bearded dragon. Her work has appeared in The Adroit Journal, NCTE’s English Journal, La Presa, The Non-Conformist, and Mslexia, among others. She was also published in the anthologies Civilization in Crisis, American Writers Review 2021, and Seeing Things (2020), and her chapbook So I Will Remember (2020). Learn more at www.wafflepoetry.com, Twitter: @JuleneWaffle, and Instagram: julenewaffle. The Banjo Lesson A small boy nestled in shadows straddles the old man’s lap. Warmth spreads, his face flush with trust and anticipation. His fingers stretch across frets feeling the press of steel on skin the soft pad of young flesh marked with pain and indentation. He plucks at strings, hears the thrum vibrating through his grandpa’s arm. They listen to the new tune its hum on the cusp of the future. Kate Young Kate Young lives in England and enjoys writing poetry, painting and playing the guitar and ukulele. Her poems have appeared in various webzines, magazines, and chapbooks. Her work has also featured in the anthologies Places of Poetry and Write Out Loud. Her pamphlet A Spark in the Darkness has been published by Hedgehog Press and her next pamphlet Beyond the School Gate has been accepted for publication in 2023. Find her on Twitter @Kateyoung12poet. Jazz Singer With shifts as long as the rolling conveyor she passes the time inventing riffs scats to the beep of electric machines taps to the rhythmic bar code scanner hums Coltrane’s Blue Train in Eb minor. Annie is decked in C major grey a checkout-girl with no middle eight to break the round-the-clock monotony of a humdrum whine looping the scale interspersed with the tap of acrylic nails. Dull, he scoffed, the bloke on deli a girl with no voice, his usual sneer as she slipped the tabard into her locker toe-tapping on sidewalks of New Orleans to the Blue Nile neon inviting her over. Ten minutes later she appears on stage the smell of jazz smoking the air in mellow tones of the saxophone the bluesy coo of a clarinet smooth buzz of brush on skin and snare. She fills her lungs with ‘Summertime’ full of swing, only Ella on her mind, spread your wings…you’ll take to the sky like a lilac butterfly, newly emerged its velvet foil on the edge of vibrato Kate Young Kate Young lives in England and enjoys writing poetry, painting and playing the guitar and ukulele. Her poems have appeared in various webzines, magazines, and chapbooks. Her work has also featured in the anthologies Places of Poetry and Write Out Loud. Her pamphlet A Spark in the Darkness has been published by Hedgehog Press and her next pamphlet Beyond the School Gate has been accepted for publication in 2023. Find her on Twitter @Kateyoung12poet. Join us April 27 online for a workshop on writing prose poetry. We're going to read some wonderful prose poems, look at elements of poetry that can work wonderfully in prose poetry, and do some fun exercises. This workshop is for poets who want to try their hand at prose poetry, and for fiction writers who want to bring new life to their storytelling. Those of you who are already prose poets will also find inspiration here. We are thrilled to have another workshop on the horizon, and looking forward to many more later this coming summer. Writing Prose Poetry: ideas, element, examples for poetry without lines

CA$30.00

Join us for an exploration of prose poetry. We will look at examples of prose poetry, along with a selection of ideas, tips, and elements that can bring yours to life. If you're a poet in love with the space around your words, come and see what the constraints of the prose form can do for your poems. If you're a fictionist, improve everything you write by using poetic elements to the best effect. If you're already in love with prose poetry, these exercises and ideas will be an afternoon of inspiration. We will be reading, discussing, and writing! Angelica’s Day Off I decided to take a day off and go to the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Well to be honest; I was told to take the day off by Doctor Smith, the Attending Physician in the Emergency Room that morning. All because of a small meltdown. But that’s a quibbling matter of subjectivity that I’m not willing to get into. Thus, I went to the museum thinking that some culture might do me some good. Hopefully pleasing, intentionally soothing; at least not sucking as much as work. Once inside the museum I went up the Great Stairway and past the statue of Diana the Huntress with her drawn bow and meandered into the cool darkness of the reconstructed Medieval Cloister on the upper floor. I paced the arcade’s stoa walk surrounding a central plaza with shuffling feet, eyes wandering through the marbled shadows at the carved filigree and fluted columns, slowing my heart in the somber false twilight in tune to the massive fountain in the middle of the room, whose falling waters trickled quietly. Suddenly a light tapping sound fell against the skylight above the plaza as hail began to fall outside, slowly at first with a discrete staccato and then in a splintering spasm and a thunderous crash as the clouds opened and gravel size pieces of the sky fell like a frozen mountain collapsing in the ether and fell precipitously onto the stained glass of the Cloister’s rotunda. I wandered out the far end of the Cloister and into the fifteenth century gallery to look at the Florentine and Milanese portraits from a century later; the Renaissance century. There was a gaunt and aged Duke in a red skull cap with pronounced and bony cheekbones staring back at me from his portrait, a somber and embittered expression seemingly gazing into the distance over my shoulder. Amused at his feigned gravity, I turned to another portrait of a fat Ealdorman’s wife on the far wall. Her face was squeezed into a stiff white wimple that framed her face like a crenellated cookie, rolls of fat descending from her tight collar, lips attempting to smile yet curved downward at the edges in perhaps the disdain of a parvenu; the nouveau riche of the newly appointed mercantile class reveling in the recently acquired wealth that was paying for that ostentatious painting. Beside her on a lacquered wooden frame was a portrait of an Archbishop in a long crimson flowing gown; behind him the painted room opened into a celestial apotheosis of circling saints in bright golden halos and angels floating on gossamer clouds in the Mysterium. Some posed in oblique with puzzled visages as if confused by their apotheosis, others stared right at me as if they could discern my puzzled face peering back at them in their tiny canvas world, centuries apart but not too distant in our merged modern expressions. One miniature beside it held the visage of a beautiful blonde woman painted by Sandro Botticelli. It was no larger than a postage stamp yet the backdrop opened into a tumbling landscape behind her posing head; a Tuscan countryside extending across golden fields where harvesters scythed and drovers whipped their oxen across muddy brown roads that meandered towards a distant village, its rounded church spire and smoking chimneys reaching into the azure sky; the landscape no larger than my fingernail. Refocusing my eyes, I stared into the sloe-eyed gaze of this Renaissance woman, now dead some five-hundred years and wondered at her vulpine look so mysterious yet direct, her hair draped with pearls and her full, rouged lips, pursed into a slight smile of pensive solitude. I admire her expression, so infinite and yet frozen in a few dabs of paint; the joyous epiphany of her face suffused with the patina of the sun through reflected clouds overhead so cleverly depicted by the artist in a few strokes of his brush. But as I wandered away, I thought about Sandro Botticelli’s subsequent folly, his decision to burn all his paintings on a pyre of decadent art, the Bonfire of the Vanities, as the mad monk Savonarola called it in his war on the Medici who controlled Florence. What use religion if it stifles this beauty, I thought. Destructive ecclesiastical jealousy of the merely human urge to absorb the human infinite into a few dabs of paint, without alms, without mortification of the flesh, without false piety. I sighed, walking away from the Botticelli, my Sunday in the Philadelphia Museum of Art at least elevating my senses from suicidal to a begrudging admiration for life’s beauties. God knows, I’ve seen enough mortification of the flesh to scorch the soul in the Covid deaths that have inundated our emergency room these past few months. People dying of this new coronavirus plague out of Wuhan, China that none of us have immunity to or the medicines to stop. The most we can do it wrestle the patients in and intubate those who cannot breathe, isolate, medicate the body’s collapse with palliatives, hoping the hand of God will spiral them forwards and not backwards in time; hoping their lungs don’t clog or their hearts stop. As a critical care nurse at the Veterans Administration Hospital, I’ve learned to wipe a man’s ass who’s incontinent; to help a Parkinson’s patient eat porridge dribbling down his cheek as his limbs twitch and his fingers shake; to stay up till midnight with an old black orderly name Dennis debating Genesis and Revelations eating his Southern fried chicken, ham hocks, and pig’s knuckles after handing out midnight pain meds to the crumpled veterans of a dozen American wars. I’ve learned to stomach anything, I guess. But this Covid epidemic has me stymied with impotence. Usually, I can be as still as a wall, or bland as a bit of white pudding in the face of a man with a broken back who looks at me upside down in his cylindrical inverted bed, as I rotate him slowly like a pullet on a spit to speed the flow of blood to his paralyzed limbs, which were last sentient when his attack helicopter crashed into Iraq a few months ago. That’s when I learned to shut my mouth and just watch; hear and see what the damaged warriors need as time creaks along on palsied knees; the difference between who I am versus who I need to be; a nurse, a pair of hands for those who can’t reach, a set of shoes for those who can’t walk, a range of vision for the blind and halt; my personality devoid of judgment so that I don’t encroach upon those whose don’t wish to be seen, touched, heard, nursed or pitied. Sometimes I wish I was a novelist or a playwright so I could tell their stories, somehow justify the sacrifice. I walk up to a painting in the museum by Hieronymus Bosch entitled “The Mockery of Jesus,’ an off-kilter world of claustrophobic architecture in a confined space; Christ, frail and tortured is displayed on the Temple balcony as the citizens of Jerusalem seethe below; only the mob’s upper torsos visible above the lower demarcation of the canvas. Monstrous faces jeer from beneath the Savior, some wearing pointed absurd hats; one man seems to have a cashew nut for a head. A few hold banners with the black figures of insects and spiders emblazoned on them. Theirs a grotesquerie of faces, half animal, some demented, all bearing witness to human depravity and the triumph of sin. Bosch was alive when bubonic plague devastated Europe, I think. What kind of man was he? What would it be like to look through his eyes at this twenty-first century world filled with another plague and the same ignorance, religious wars and starvation, all driven by a fanatical faith in an apparently indifferent Supreme Being? What is different today? What themes would I chose if I was an artist instead of a military nurse? What madness in my gaze? Would I see what Hieronymus did in the dungeons of his skull, a flat two-dimensional world filled with claustrophobic dread? Or would I perhaps be more ferocious, show courage over indifference. Who knows? I wander down the hallway of the museum thinking about nothing and everything, the tall ceilings in the museum like a church nave, the hushed voices about me like communicants making their way to the altar rail to receive the bread of life, the sunlight streaming through the high windows splashing color onto the whorled canvases like sunlight filtered through a church’s stained-glass windows. My mind is seized sequentially as I walk, each painting pulling something new from me, midwife to my emotional birthings, sliding daydreams into the folded images from the hospital ward until I turn a darkened corner and abruptly realize that I’m in the Medieval Armory. Above me on a rampant black stallion, its forefeet raised in salute, is the figure of a helmeted knight in brightly polished armor. He wears a decorative steel cuirass over his chest and on his legs are bright greaves. He holds a black enameled shield in one hand with a tapered lance thrusting forward from beneath it, which points on into the tapestried hall that’s decorated like a castle’s keep filled with archaic weapons. This was my son, Eric’s, favorite room. The one he’d race to whenever we’d come; anxious in his four-year old body to get out from under all the disproving gazes of the Madonnas and Christs in the Renaissance Hall; or wearied by the black and white Mark Rothkos or the blue Pablo Picassos that hung with smug condescension in the Modern Art exhibit. It was always to the Armory that he’d run with open arms and stare in wonder at its terrible beauty; death raised to a religious chivalric certainty as if God in another age had anointed the ‘Knights Errant’ as progenitors of good death in ages archaic yet surprisingly familiar; the armor reminding me of modern Kevlar body armor and its inability to stop the gaping bullet wounds I treat back at the hospital. How Eric loved to roll the names of the French weapons off his tongue; basilard, halberd, glaive, and arbales; the elisions of the Romance language as liquidly deceiving as the beauty of the pointed spears and polished lances that line the walls in hermetically sealed cases, ostensibly to keep the humidity from reducing the death's agents to so much useless slag. I feel the tears coming unbidden as I look across the room, the memory of Eric running from case-to-case so vivid and so vital that I almost feel the need to run myself, chase after his ghost before the guards catch him up and threaten removal. The salted tears trickle down my cheeks as my breath takes and the soft sobbing comes. Nothing can stop it now, I fear. The winds of time spiraling backwards, and there across the hall I see Eric at twenty-one in his dress Marine uniform, his immaculate white pants and sea-blue blouse, his shoulder epaulets flashing with gold and ivory. Lieutenant Eric Broussard, Annapolis Graduate, shortly headed for Iraq after one last visitation with family and friends in Philadelphia to his favourite haunt. I walk over to the window and look down upon the broad back of the Schuylkill River, a long granite impoundment stoppers the water, the dam an absurd impediment to the insistent cataract that falls in white foam and flume. The summer hail has stopped and a light rain is falling as two geese balance incongruously upon the lip of the spillway and the thin film of water that roars downwards. The white geese are oblivious to the rushing water astride their feet as they peck and bicker, suspended in a motionless eddy of water and sky. Helplessly I smile at their silly disrespect for the power of the river and look past them to see a ten-man skull pulling upstream, its rowers and their long oars stroking like centipedes against the spilling current. Along the banks and up in the cliffs are trees with green crowns like broad-leafed hats hanging from the rocky overlooks and groves of red and orange azalea bushes that march along the cliff-face like flocks of drowsing sheep. The Schuylkill River bends to the right about a mile above the dam and then disappears, pulling my gaze across the river and up towards the towers of the Veterans Hospital in the heights. I can see the windows of my ward, my mind’s eyes speeding outward and into the wing where I tend my own flock, the poor disembodied ones, the soldiers who left their limbs on the golden sands of the fertile crescent; some blind, some gouged or whipped senseless by the vicious anger of men they'd never seen before; only to come home to Philadelphia and my shift of nurses, who quietly put them back together again, holding them at night when they cry, slipping them candy like little children to make them smile, suturing their amputated stumps with black cat gut stitches, and covering the ragged remains with red iodine-stained bandages. The tears turn my eyes to mist as I gaze further along the river, see the military cemetery atop the farthest hill, the spirits of boys who’s not come back, lingering there, out of sight and behind the distance. Eric is there in his blue uniform as he wished. I wipe my face with my sleeve and leave the room in a rush, angry for letting this happen. I thought I’d steeled my heart, no more backward glances, always to the future and never back. The corridors flame about me as I rush through the cool shadows then halt as I feel people staring at my haste. What do you do when the hole in you gets so big, the edges sharper, the vortex spinning deeper, and yet the video outside of you spins by unconcerned with your loss, passers-by no more than two-dimensional strips of flesh skating past like Gumby characters staring at you with his wide-eyed Play-Doh incomprehension as if you’re the Claymation character and not him? I slow and turn down a random corridor and stop beside a tall carved altar purchased by some American Philanthropist depicting the passion of Christ and his Stations of the Cross in decorative woodwork. I stare transfixed at the tiny ancient figures, carved in such minute detail that each biblical personage is singular, down to the cuirasses and plumed helmets of the Roman soldiers and their grimacing expressions, as they pound black nails into the soft flesh of Jesus’ unflinching palms. The Madonna's long shawl covers her body with a slow graceful arc that seems to anchor her flowing body to the side of the altar like a blossoming flower. Her expression draws me closer, numb with grief, but the eyes, the eyes seem to flicker with anger. No mother accepts this, I think. No mother will believe all is for the best when they take her son, strip him, torture and hang him on a cross for the entire world to mock. No mother would believe that has value. Why don’t you throw yourself at those bastard soldiers, I whisper at the Madonna? Why do we always stand around and watch them grind our children like meat to the slaughterhouse? But finding no response from this wooden, centuries-old representation of the mother of God, I walk on, my mind sliding sideways in helpless response to my surroundings; paintings and statuary beckoning at random for my attention at the periphery of sight. Again, I hear the soft trickle of water and another fountain appears, this one in the atrium of the Impressionist Gallery. It’s a round golden room under a curving rotunda and against the farthest wall, as if reposing before the flowing waters of the small fountain, is Paul Cezanne’s painting The Bathers. Like the Botticelli, it’s another blue-sky painting but this one gigantic taking up an entire wall with a dozen nude women laconically lounging beside a deep flowing river, their sun-browned bodies relaxed and eternal like nymphs of the Goddess Diana. The bold impressionist strokes of colour are representationally unfinished, yielding form only from the colour swirls that elusively creep through the riverine perspective, creating the women’s shapes out of dabs of red and beige, the flesh transmogrified into something else, devoid of the lineament. Two opposing groups of women face each other in the painting, some gesturing as if deep in discussion, while others lay languid and supine gazing across the river towards a Chateau in the distance with high rounded towers. Trees arch over the naked women, framing them in a pyrimidical curve that draws the eye upwards and towards the clouds. I look around the rotunda, its benches filled with silent viewers, their faces suffused with looks of deep harmony in meditation; perhaps the fountain a cool continuation of the river flowing past us on the canvas; the echoing falling water of the fountain under the rotunda a baptismal font for cleansing our sins; or maybe it’s just women being women, waiting in solitude without a man to disrupt their serenity. I notice that none of the women in the painting make eye contact with one another, they are all looking in different directions away from the viewer - except one. One woman stares directly out of the frame at me in a discerning and insistent gaze. With a start, I realize she has no mouth. Cezanne left it unfinished or perhaps an intended omission. What use a woman without a mouth, I think. Suddenly a small girl rushes out from hiding beneath her mother’s skirt and shrieks with echoing laughter into the austere hollow of the rotunda. She throws her tiny hands into the fountain and splashes her mom then runs away with her mother in hot pursuit, chasing the giggling child around the fountain as we all laugh with them. I look up again at the mouthless woman leaning against the tree, her arms limp by her sides, breasts heavy and uneven, as if she’s recently suckled a child, her shape arching along the curve of the dark brown trunk like a drunken caterpillar. And for some reason under that placid woman’s gaze, I feel the world still and the roaring in my ears cease. Unconsciously, I place a hand over my heart and feel the pulse of it slowing under the painted woman’s gaze. The child is caught and gleefully chastised. Life moves. Life is insistent and inexorable and painfully vivid and sometimes mysteriously vague but we have no choice but to move with it or die. I suddenly realize it’s time to go back to the hospital. There are things that need to be done, things that I can do. Thomas Belton Thomas Belton is an author with extensive publications in fiction, poetry, non-fiction, magazine feature writing, science writing, and journalism. His professional memoir, Protecting New Jersey’s Environment: From Cancer Alley to the New Garden State (Rutgers University Press) won “Best Book in Science Writing for the General Public” by the New Jersey Council for the Humanities. https://www.rutgersuniversitypress.org/protecting-new-jerseys-environment/9780813548876 In addition, he has published many short stories including for the journals Fterota Logia, Mystery Weekly, Mystery Tribune, Constellations, South Shore Review, The Satirist, Adelaide, Meet Me at 19th Street, Cicada and Art News. His short story “Seneca Village Arises,” (Meet Me @ 19th Street Journal) was awarded “Best First Chapter” in the journal’s 2021 contest for a Young Adult novel opening dealing with racial inequality and his short story “Murder at the Trocadero” won the “Writers Digest Writing Contest Popular Fiction Award” for Mystery/Crime (2017). Patrizia Late February 1909, Nice, France The day had been a good one. A wisp of chill air had awakened him, filling his nostrils with the salt of the sea,which, in his view, was the finest way to wake up. Throwing back his white down comforter, he simultaneously plopped his cat Georgina onto the polished oak floors, where she responded with a languid yawn and then a ripple of purrs as he quickly bent to indulge her in a lengthy scratch. Light was just peeking into the room from the floor-to-ceiling bedroom windows, one of which had been slightly open all night, letting the muted snores of boat horns sounding in the harbour and the laughter of patrons returning from parties celebrating Carnaval punctuate his dreams. When he pushed back the heavy ruby damask drapes, the harbour’s reflections made the room come alive with shimmering pinks and azures and hints of silver-white. A soft ray illuminated a tiny self-portrait---a quick sketch in charcoal and ink--of his teacher and mentor, Louis Hector Leroux. René smiled in remembrance of the man who has graciously set him on his life’s course—and who had told him, “The women in Nice are beautiful. You will have plenty to paint.” How true that had been…. He had an appointment at nine-thirty at the café next to the Maison Auer, giving him just time enough to slip into the Maison and purchase a small box of their Cakes aux Fruits confits, Patrizia’s favorite of all the delectable specialties in the marvelously decorated Florentine-style shop. There was something about gilt and crystal and shelf upon shelf of artistically arranged chocolates that made him feel good to be alive. There would be time, too, to drop by François Aune’s creation, the Opera House of Nice, to reserve tickets for the upcoming performance of Franz Lehár’s La Veuve Joyeuse, a rare chance to hear René Lapelletrie of Paris, along with Nice’s own, soprano Paule Marelly. Leaving his appointment (another commission for yet another Portrait of a Young Woman), he wended his way from the rue Saint François de Paule to one of his favourite places in Nice, the Jardin des Palmiers. At the Swan Pool, he watched a mother give her daughter a half a baguette, which she, in turn, broke into smaller pieces to toss to two swans, who gobbled them up, much to the little girl’s delight. At the Fountain of Tritons, he had stopped to take in the display of iridescence as the spray of the fountains danced in the deliciously strong late-February sunlight. Abandoning the pathway of palms, he strode onto the center of the great lawn set in the axis of the Paillon, standing completely still for several minutes, letting the sun warm his back and the sea breeze cool his face, a simple luxury he often gave to himself. Then, to end his stroll, he meandered into the sinuous alleys closer to the seafront. His feet then found themselves walking westward to rue Gustave-Deloye, to his neighbourhood synagogue. Its neo-Byzantine ivory stone façade with its pyramid-shaped summit pierced by a central rosette and capped with the Tablets of the Law sheltered the carved olive wood doors that welcomed him. Soft light bathed the cool inside, where several scattered worshippers sat silently in prayer. To the tip of the red Magen David inlaid in the white marble floor he moved, allowing the flickering glows of a raft of candles to accompany his contemplation of each corner of the star: creation, revelation, redemption; man, the world, and God. A feeling of beneficence and strength flowed through him, the second gift of the day. As he turned to leave, an old man looked up from his prayers and met René’s gaze with a wistful smile. Outside, the distant sounds of the Corso Carnavalesque on the Boulevard des Anglais drew him to go near. Cheering and clapping accompanied the beat of drums and the blaring of horns. He had missed only a few since the age of seven, when the Niçoise artist Alexis Mossa put his distinctive stamp on it, reinventing the Carvaval into a parade and adding masquerades, floats, and competitions. René would take Patrizia to the Battle of the Flowers tomorrow. With the thought of her name, he pulled his watch from his pocket, noting the hour, 11:27. Her train from Venice would arrive at 12:42. She had been away for over six weeks, since the day after his birthday on January 5th, writing that Venice was dreary, but reporting that her family had replaced the fog and gloom with many parties and dinners in her honor. Her family, patrician to the core, their eighteenth-century palace dominating the edge of the Grand Canal, its façade strewn with fabulous marble animals. He remembered his visit there at Noël and how they had entered into its quiet from a bustling calle, she unlocking the courtyard with a key that was so large and heavy that it could have opened the gates of the city. “The garden first, before the house,” she had whispered. Then they passing through a vaulted passageway and crossed two doors to arrive at an interior courtyard. In the centre was a well. In the well was a clutch of turtles with scores of hatchlings. It was magical. As had been everything there. In her first correspondence from Venice, Patrizia had informed him that the turtles were “as fit as ever” and “doing just fine.” Her last letter, arriving yesterday, was, however, a bit enigmatic. “Please do not break up your day by meeting me at the station. With the help of a porter, I can manage my trunks. Besides, I have a surprise I want to save until our dinner.” Indeed, she could manage—as she had shown so well. Her millinery shop on the Place Massena was a favourite of all the fashionable ladies of Nice. Even so, he imagined her lace-up boots clicking on the tiles of the cavernous Louis XIII-styled station, her signature diamond earrings flashing under the illumination of the grand chandeliers, and he assented that the richly decorated balconies could be peopled by a host of ready admirers. He edged his way onto a small step where he could watch the last three floats pass. The merry crowd on the "Concours de Musique" waved to the spectators as red-coated gentlemen puffed their tubas into resonant rumblings and a twelve-foot tall mechanical conductor directed the three jesters cavorting on a tower, trumpets in hand. Next was a riotous carriage of fat-cheeked, screaming babies, an oblivious mother, her husband at the helm, brandishing a “whip” tipped with ears of corn, which kept at bay a cloud of white doves that seemingly, simultaneously carried the carriage aloft and glorified the procession with their never-ending sh-sh of wings. And lastly, the “Char des Pompiers,” an impossible contraption of tubes and tires, all marvelously fun. As the parade ended, Niçoises and tourists alike converged onto the Boulevard, and René navigated through the hordes, heading decidedly for the Jetée Promenade, the 1820s crystal palace, so loved by the English, who flocked to Nice to take in the winter sun. Standing on the wooden pier leading to the entrance, taking in the midday rays, he wondered briefly if he didn’t have a bit of British blood in him, for he, like them, wasn’t all that keen to get into the waters of the Mediterranean, however compelling they might be, but preferred to look at them. But the moment could be only a moment, for there were many other things to do. First stop, the markets on the Cours Saleya… The vegetable market: fresh eggplants, zucchini, tomatoes, and red peppers. Then to the wine stall of Monsieur Caprioglio. His suggestion, as always, was promised to be just the right match for René’s planned ratatouille. “I had it myself last Sunday. It is a delicious Barbera from the Piemonte, made by my old friend Giacomo Oddero, the vines from an impeccable natural terrace overlooking the hills of the Langhe, near the village of La Morra…. The color is extraordinary: ruby-red with tinges of purple. For your special dinner tonight, you couldn’t find a better assistant….” His wink was clairvoyantly conspiratorial. As René tipped his hat in reply, M. Caprioglio added, “The next time you stop by, my address may have changed. I have almost finalized the project of my dreams. On the rue de la Préfecture, a shop has become available for sale. I have talked with my banker, and…” “My most sincere congratulations! You can count on me to be a regular customer!” René enthused, and with that, he turned, for his final stop, the striped awnings of the flower market, which would provide the ultimate pleasure: row upon row of lilies, tulips, impatiens, dahlias, and anemones. Today, however, a pair of entwined lilies were his prize. His breath caught when he saw them. He divulged laughingly to the genial vendor, “Prescient? Perhaps. And Patrizia’a favorites… Couldn’t be more perfect.” His pace quickened as he headed for the Place Masséna. After he crossed the Pont-Neuf with only a cursory glance at the Paillon River lugubriously making its journey to the sea, waiting patiently, as it must, for the spring melt of mountain snow to invigorate its flow, the grand square opened up before him. Alive with trolleys and carriages and shoppers, it was the whole world in miniature. Sidestepping three women walking arms locked, all sporting incredibly large black parasols, he noted the sign on Patrizia’s shop, penned in her fine Italian hand: “FERMATURE ANNUELLE--jusqu’au le 2 mars.” Inside, the hat stands were covered with white cloths, and the glass counter wore a thin coating of dust. Soon. She would fill it with her charm and her laughter. And, of course, the scent of Orange Blossoms, the A. A. Vantine & Co. fragrance that she was never without. Looking through the windows, he remembered the early November morning that he had met her, stopping in with his mother to buy her a hat. While his mother oh-ed and ah-ed over the well-appointed and impossible-to-choose array of possibilities, his eyes could not leave the raven-haired proprietress offering deft suggestions to his mother. Her lithe hands had lifted each creation to place it at just the right angle onto Madame Avigdor’s head, and her radiant smile as both women admired the result in the mirror did—just for a moment—seem to change ever so slightly as her eyes caught his eyes watching her. He had come back the next day, to thank her for his help with his mother, and, most certainly, to ask her to dinner. It happened so quickly after that. Dinners, lunches, a three-day trip to Venice to meet her parents—and to catch Giuseppe Verdi’s Aida at Teatro La Fenice on the 26th. And yet… He, at age 41, had decided that he no longer believed in love. But there it was, a moment of grace. She was his first love, his last love, something exhilarating, like skydiving without knowing if the chute will really open. She had peeled back all his defenses. When one arrives at the heart, everything changes, because having nothing to lose, the heart opens to the world. And yet… His thoughts whirled as opened the door to his apartment—and studio, three flights up in a fine Italian red-brick building on the northern side of the Place Masséna, a gift from his father, a very prominent lawyer in Nice, after René had received his first big commission. “You will need a studio close to your clients,” he had explained. After giving Georgina a scratch, depositing his market offerings in the kitchen, and finding just the right vase for the lilies, he turned his attention to his studio, where his Rodin dans son atelier awaited his final touches. He carefully laid his sack coat and vest on a wooden chair and donned his artist’s smock. He worked steadily for several hours, and, as the afternoon light started to fade, he felt pleased with his results, standing back to give the painting one last critical gaze. The master, he felt, he had captured well. After all, portraits were his métier. But the sculptures in the painting made him especially proud, for making marble come alive in oil had been his own private challenge. His eyes lingered over The Kiss. “Bien fait,” he said allowed. The couple’s tenderness was palpable…. Maybe tonight? But there was dinner to make, a table to set, a bath to be drawn. By 6:52, all was done. Finely attired in a dark tailcoat and contrasting waistcoat, he set about to ready the music. The gaslights of the square glittered through the windows. Two candles flickered on the mantle. He selected Satie’s Gymnopédie No. 1, which seemed to him to reflect his mood: wistfulness, longing, anticipation. Yes, maybe tonight. He had just placed the sapphire stylus of his Amberola on the wax cylinder when there was a knock on the door. The music filled the room. She was here. Patrizia. His hands shook as he opened the door. Their eyes locked. Her red hair was loosely pulled up in a softly swirled chignon. She wore no earrings. A mid-calf fur frockcoat draped from her delicate shoulders, and her slim feet were tucked into black pumps with pearl buckles. A hint of lace peeked out from her slightly opened fur. Her ivory skin glistened. Pressing a finger to his lips to halt any words, her other hand released the comb in her hair. She stepped into the room and closed the door behind her. The fur fell to the floor. Except for the pumps, there was nothing but the lace camisole. Nothing and everything all at once. He took her into his arms. Dinner would wait. Yes, the night would be a good one, too. Debbie Robertson Debbie Robertson divides her year between the United States and France, loving the summer and winter skyline sunrises of Houston, Texas, and reveling in the spring and fall mountain sunsets in the Alpes de Haute Provence. Her works have appeared most recently in Toute la Vallée, a French journal. She has written plays and “operas” for children’s theatre, and parallel text (English-French) short stories. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|