|

Late Afternoon Under the Weeping Willow in Ashland, Oregon

Two black wrought iron-chairs and a matching table. An old couple talks about how the lovers in the play missed true love, accepted good enough, veered away from a leap of faith. Settled. One actor clung to a dock, another jumped into mud-suck. Though each was heir to a salvation, both lived out their lives as they had always lived. Riffles of waterfall backgrounds the swish of new-spring leaves. The pair in the stiff chairs? They recall flash-in-the-pan gold, the fish that get away, how easy to err, standing still. Through the veil of the willow, hand in hand they meander into evening. After the sun sets, two empty chairs. The willow stills after vanished wind. In the pond the frog chorus sings “creek” and then “free” and finally, maybe “right,” mating calls of the warm spring night tucked in the sweep of the willow’s reach. Tricia Knoll Tricia Knoll’s poetry collections include her full-length book Ocean’s Laughter (Aldrich Press, 2016) and her chapbook Urban Wild (Finishing Line Press, 2014). Website: triciaknoll.com

0 Comments

South Carolina Morning

Well, I know I look fine in this red dress, but no one in this swamp has any taste. I’m so tired of pale grass and emptiness, this too-big sky, this heat as thick as paste. I only came because Belinda Ann laid on the guilt: “We haven’t seen you, Kitty, for ages now.” Three years ago I ran away from this backwater to the city-- but I have missed my Daddy, so I’m here. Now Mama mutters that my hat is fussy, the neckline of my dress too low; it’s clear she thinks high heels make me some kind of hussy. If she unpursed her lips, I think she’d hiss. And I got myself all dolled up for this? Yes, I got myself all dolled up for this big party—Daddy’s turning sixty-eight. He’s dozing, probably content to miss the half-baked revelry. He’ll celebrate in bourbon’s blurred embrace; he’ll hardly see Aunt Kate’s dog shedding in his Morris chair, Belinda Ann’s dim-witted husband Lee, their bratty kids, my brother Al’s long hair. I know my Daddy; I know how he dealt with years of Mama’s miserly affection; I’m sure he just tossed back an extra belt the day of my undaughterly defection. This party reeks of all he can’t abide, so he indulges in slow suicide. While he indulges in slow suicide, I save myself, abandoning the heat of family friction, venturing outside, but finding no relief in my retreat. I breathe in something cottony and thick, the same damp flannel that weighs on my skin. Both air and history make me feel sick; I crave some other atmosphere and kin. Belinda Ann, dear sister, grinned with spite when Mama blanched at my V-neck; Aunt Kate half-sputtered that my dress looked mighty tight; while Al shot me a leer of need and hate. I know that I should go back in there soon. How will I tolerate the afternoon? How will I tolerate an afternoon of righteousness and rumours and regret? Hell, will I last the morning? That buffoon Belinda Ann got married to has set his mind on getting Daddy’s ear; he’s yelling some birthday toast, and then he yells at me to come back in. Well, he sure isn’t telling me what to do. I try to smell the sea; it isn’t far, but you would never know that wind and water move around nearby. It’s all so still and stagnant here, below the heavy oilcloth of this dense blue sky. Unchecked, this sun would ruin my complexion; this hat’s for style, but also for protection. My hat’s for style, but also for protection against the unrelenting glare that burns and wrinkles you. I have quite a collection of hats and shoes; in town, my wardrobe earns me lots of compliments. I guess I should have known that back here I’d look out of place; three years ago, nobody understood why I was leaving. But I like a space that’s filled up with storefronts, light poles, and cars; I like the whoosh of a revolving door and big screens lit up with big movie stars-- yet here I stand. And though I can ignore Al’s envy, Aunt Kate’s frown, and Mama’s grumbling, I can’t quite shrug off Daddy’s drunken mumbling. No, I can’t shrug off Daddy’s drunken mumbling or his vague absence—not unlike my own: he too has stepped away from all that fumbling for happiness, his heart a well-soaked stone. He numbs himself against frustration’s ache, but I escaped and found another world, where color, crowds, and noise conspire to slake all kinds of thirsts; where better booze is swirled in fun instead of fury; where you seize the day, it grabs back, and you feel alive; where heat comes in the lazy, lusty wheeze of late-night saxophones. Well, maybe I’ve deserted Daddy, but there was no doubt I had to go—I just had to get out. I had to go; I just had to get out of this hell-hole before I suffocated, and that’s how I feel now. Mama can pout, Belinda Ann can push her overrated peach pie, but I won’t stay to eat a slice; my favourite clothes won’t fit if I get fat. I don’t need their approval or advice, their false concern, the drawl of their chitchat, their honey cut with bile. I’ll take off just as soon as I can manage it. I’ll swap blank air for busy streets; I’ll leave disgust behind; I’ll go where I can dance and shop, where car horns blare with someone else’s stress, where I know I look fine in this red dress. Jean L. Kreiling First published in The Truth in Dissonance (Kelsay Books, 2014): 44-47. Jean L. Kreiling’s first collection of poems, The Truth in Dissonance (Kelsay Books), was published in 2014. Her work has appeared widely in print and online journals, including American Arts Quarterly, Angle, The Evansville Review, Measure, and Mezzo Cammin, and in several anthologies. Kreiling is a past winner of the Great Lakes Commonwealth of Letters Sonnet Contest, the String Poet Prize and the Able Muse Write Prize, and she has been a finalist for the Frost Farm Prize, the Howard Nemerov Sonnet Award, and the Richard Wilbur Poetry Award. Harmony in Blue and Gold

I had no knowledge of the Peacock Room. By hand she led me to the centered bench and sat. I stepped away and turning back saw her within her setting a first time. It's gold and blue, if you must know, the walls hand painted in repeating patterns. Frames become the room, and vases, blue and white, are everywhere in formal disarray. It's like a room of verse. Pentameter is just that, free but formal, like her clothes, and just as rare: there is no other room like this one, which is how it earned her love. I made a promise to her then: to build a room like that, and did, but now I think these verses have become her Peacock Room where she may live within what's beautiful. W.F. Lantry W.F. Lantry’s poetry collections are The Terraced Mountain (Little Red Tree 2015), The Structure of Desire (Little Red Tree 2012) winner of a 2013 Nautilus Award in Poetry, The Language of Birds (Finishing Line Chapbook 2011) and a forthcoming collection, The Book of Maps. He received his PhD in Literature and Creative Writing from the University of Houston. Recent honors include the National Hackney Literary Award in Poetry (US), CutBank Patricia Goedicke Prize, Crucible Editors' Poetry Prize, Lindberg Foundation International Poetry for Peace Prize (Israel), and the Potomac Review and Old Red Kimono LaNelle Daniel Prizes. His work has appeared widely online and in print in journals such as Aesthetica, Gulf Coast and Valparaiso Poetry Review. He currently works in Washington, DC. and is an associate fiction editor at JMWW. Cave Man India 1853. As Buddhist monks chanted very quietly outside, a bearded, disheveled, dirty, paint covering his face and clothes, Preston Morrison slept on a carved nook in the rear wall of a cave, a blanket covering him. There was a large sketchbook beside him, on the wall hung his army uniform, and leaning up against the wall was a gun. The entrance to the cave was directly opposite to him, and beyond the entrance a cliff. It was daylight, but Preston had worked all night at his copying and forgot to snuff out the small fires across the front of the cave entrance to scare off wild animals. The light from the fires revealed that all of the walls of the cave were painted, though they were too dark and distant for anyone but Preston to see them clearly without a lantern. In the centre of the cave was a massive sculpture of Buddha, whose head almost reached the cave ceiling, and around which there was sufficient room to walk. * The tour guide entered the cave, stepped around the fires, stopped and spoke to the tourists in a styled, arrogant, insincere and professional voice. “Now please stop here and huddle together so that you can see this fresco behind me. Watch out for the fires which the natives use to frighten off tigers when they are working or, if monks, when they are sleeping. “This particular work, only partially restored for reasons I shall explain presently, was painted by local artists and wandering Buddhist priests while taking respite from the monsoon and inclement weather. No one knows the names of these artists, but we do know that many of them were ascetics who lived off the local villagers and traveling tradespeople. To these and other caves they would come for meditation and community with other monks. “You will note that most of the symbols of the work have been damaged or obliterated. Various religious zealots from different sects attacked the work and in some cases would slice it off the wall. What remains is a bodhisattva—a being that foregoes nirvana in order to save others—garbed in the fashions of the princes of those days, holding a lotus flower. Note how well the artist has captured the real-life posture and expression of the body, and how transcendent is the look on the bodhisattva's face.” “Please follow me quickly,” the tour guide said, “and we will examine a different kind of Buddhist cave next door.” * Preston was having a nightmare, one of many. For a minute he moved around restlessly in his bed, groaning and talking incoherently, then he jumped out suddenly, grabbed the gun, pointed it forward, walked around the statue as if searching for something, mumbling to himself without sense. His eyes were very large and scared. He then returned to his bed and laid down. A minute later he was startled by what he thought were the growls of a tiger beyond the entrance to the cave. He anxiously grabbed a thick stick, ignited the end of it, and walked to the entrance waving the lit end. The tiger, he thought, snarled and continued to growl. Preston walked back and forth across the entrance waving the stick at the tiger. He leaned down and threw a few sticks on one of the fires that seemed to be going out, yawned, returned to his bed, and laid down, exhausted. Then the tiger growled again, much louder, and only stopped after Preston sat up, shook his head, then picked up his sketchbook and the burning stick, walked over to a section of the cave, shoved the stick in the wall for light, opened up his sketchbook to a particular page, yawned, and began to copy the paintings sitting in the same lotus position as the statue. He painted for a while, then his head dropped and he fell asleep. The fires went out and the cave became dark for a brief period, then a dim light returned. * The tour guide returned with another smaller group of people and stood in front of the Buddha. The tourists stood to the right of the Buddha. “Please watch your step,” the tour guide said. “Sir! Please do not wander off. Thank you. The lights as you can see are very dim in this cave because the paintings on the walls are very sensitive and are slowly deteriorating even without light. You’ve been told not to take any flash photographs and I would hope that you’ll abide by the rules. These caves were usually either living quarters or places for religious ceremony and meditation, and were carved out of solid rock. Around the edges you would see paintings of the various reincarnated lives of Buddha, known as The Jataka Tales. In the center of the room would be an enormous statue and/or a bell-shaped structure. Let us walk around it and exit.” They slowly walk around the sculpture of Buddha as the tour guide continued. “This path we are taking is the exact path that the Buddhist would take in meditation. People did not live in this sort of cave. You will not notice any of the little stone ledges or rock-cut compartments that we have seen in other caves. This cave was only for meditation and ceremony. Imagine if you can what it must have been like for these people of old, in a time when there were still many Buddhists in India, and how these monks chipped away at this cave rock to hollow out these caves for revelation. Imagine also how they expected no recognition and yet they created these wonderful works of art. My assistant will now briefly flash some light on each of the paintings around the hall. Please do not touch them or come too near them.” A spotlight moved across several paintings as the tour guide and tourists left the cave. * Preston was in the lotus position with his head hung, the sketchbook on his lap. However, at every wall and at the sculpture there stood monks in long orange hooded robes painting. sculpting and repairing. The monks disappeared when Parvati, a young local woman, Sanchi, her father, Commander White and Lieutenant Fisk, two British army officers, entered, all out of breath after climbing the cliff to reach the cave. White and Fisk violently swatted at bees as they entered. Parvati carried a sack and Fisk two large bags. They saw Preston asleep. White, Fisk and Sanchi walked around and looked at the frescoes while Parvati shook Preston gently. Preston awoke and saw Parvati. “Parvati!” he said joyfully. Preston reached out to hug her but she shyly pointed to the others with her. “What bliss! To see your face first as I open my eyes.” Parvati took his hand and brought Preston to Sanchi, Fisk and White, and they greeted each other. “And my friend returns,” Preston said to Fisk, “looking weary from the journey, even dragging up the mountain the Commander. Welcome!” Preston shook heartily the hands of Fisk and White. Preston extended his hand to Sanchi. “And you, father of Parvati, will always find a friend in me. Thank you for coming. You may now see how brilliantly your daughter has copied some of these works. But all of your eyes tell me that you all bring some sad message.” Sanchi shook Preston’s hand. Parvati excitedly ran over, picked up the sketchbook, returned, and showed proudly Preston’s work to Sanchi, White, and Fisk. They all examined the book. Preston went to a corner of the cave, returned with a bag of coins and offered them to Sanchi. Sanchi took the bag and looked inside it. “A small reward for your people helping to unearth this artistic miracle,” Preston said. “I thank you for your gift,” Sanchi said with a heavy accent but clearly. “And I thank you for your most kind affection and admiration for Parvati. Still I must speak to you openly and sadly. I and the others of the village have become fearful of this place. Many think we should have left the caves untouched. Our villagers have had many misfortunes since we cleared the caves out with you. The tigers have multiplied. None of the villagers want to continue the work, and I urge you too to abandon this place too. We fear for you. Here the tigers now rule. Here many men have died. What does this mean? It means that Allah does not want us here. Indra has cursed us all. I hope and pray that you will leave for your safety. “I have also forbidden my daughter from returning, since there will be no one to accompany her. If you want to see her, you must come to the village. And I believe that the people of the village will not accept her if she comes here anymore. They will call her sorceress.” Sanchi waved his arms around the walls. “All of this is against the prophet and should remain in darkness.” “Sanchi,” Preston pleaded, “we have trod this path before. There is nothing to fear...” Sanchi shook his head, waved his hand to interrupt him, extended his hand to Preston, shook it again and quickly exited, beckoning also Parvati. Parvati and Preston approached each other closely and looked into each other's eyes for a moment, then she departed with Sanchi. “Parvati,” Preston said tenderly and quietly. He followed after her to the cave entrance and stared as she descended the gorge. Fisk and White meanwhile observed this scene and exchanged glances as Preston continued to watch Parvati and Sanchi walk down the mountain. Fisk put his arm around Preston’s shoulders. “How are you, my old friend?” Fisk asked. “How am I? My condition? Tired. Often sick,” Preston says, still looking in Parvati’s direction, his tone of voice without its prior enthusiasm. “The bees and tigers won’t let me sleep. But what matter? My work continues. Now I fear I shall be alone, abandoned by the villagers and Parvati.” During the following conversation, Preston gathered some of his paints and brushes, walked over to the spot on the wall that he was copying, picked up his sketchbook and began to paint the area of the wall he had worked on the previous night. White and Fisk follow him. “We were attacked by the Bhils,” Fisk said. “They only scattered when we showed our weapons.” Preston laughed heartily. “They are a harmless tribe if you have weapons,” Preston said. “They haven’t come near me for months…Parvati says that they think I’m mad. They call me Tiger Man because they think I’ve killed one hundred and fifty tigers.” He laughed again. Fisk gave White a worried look. “What will you do now about Parvati?” Fisk asked “What any man does who misses his inspiration,” Preston replied. “He moans and grumbles and mourns. Such beauty, kindness and talent. But she is a daughter, and has a duty to her father who overwhelms her with fear of abandonment. “Fisk, her talent is greater than mine and equal to any of the cave artists! If I could keep her here, working, painting, I would, but you heard Sanchi.” “Is Sanchi right?” Fisk asked. “How many people have the tigers killed? Sanchi tells us the white rags hung on the bushes indicate another killing.” Preston nods. “But there are white rags waving everywhere!” Fisk said. “The bushes look as if snow has fallen.” “Many have died because they don’t understand the tiger,” Preston said. “I don't know how many!” White and Fisk glanced at each other again with faces of alarm. “My God, Preston!” Fisk said. “Tigers, crazy tribes, angry villagers. This is madness! In light of that, perhaps our news isn’t as bad as it might appear. And please, listen to me, as a friend, before you judge. Will you listen?” Preston nodded, but continued to paint. “At headquarters they want you to drop this project—but only for a short period—and return to duty. The war against Russia has started!” “Wars spring up and die like dandelions,” Preston said, “while this work is a sacred duty. What good is a painter in a battle?” “This project too can wait,” Fisk said. “The caves will be here.” “Wait? Wait?” Preston shouted. Then his anger ended. “Have you informed them that they march for tokens and trample on beauty?” Then Preston added with a tone of sarcasm, “Perhaps your war can wait.” “You must listen,” Fisk said. “They are no longer interested in a soldier copying ancient wall paintings. Your responsibility is elsewhere, your talents are needed elsewhere.” “Images endure but paint decays and disappears from time and the hand of man.” “You’ve been here nine years!” Fisk said. “Look at you! You've aged twenty years! I left you a young man, but now, now your hair is turning gray. You should stop for your health if for nothing else!” Fisk saw a scar on Preston’s arm. “How did you acquire that scar?” “I was trying to help a wounded tiger and it accidentally scratched me.” “How many caves have you finished?” Fisk asked. “Art is never finished,” Preston said. “This is the last cave, isn’t it?” Preston did not answer. “Preston, you’re still in the army. It’s time to leave India. When the war is over, you can return.” White had been walking and staring at the paintings on the opposite wall. “These are not Christian images, are they, Lieutenant?” White asked Fisk. “No sir,” Fisk replied. “They reflect the Buddhist faith.” “Then why are we so concerned about them?” White said. “Why has the department allowed Preston to remain here at all?” “Commander Wylie,” Fisk explained, “your predecessor, was here when the discoveries were made, and Lt. Preston convinced him that they were of great cultural and artistic worth, created by artisans and monks over many centuries with what he believes are the finest creative talent. The artists actually lived in some of these caves as sanctuaries and retreats. According to Preston, nothing in their time is comparable in the West or East. If they are not copied, they may disappear forever.” “Do I understand you?” White asked. “Preston is an army draftsman, trained and employed by the armed services to serve its needs. Are you saying that we are supporting him in...?” “The army hasn’t financially supported Preston for several years, sir. Commander Wylie simply refused to recall him.” “So we are allowing one of our staff to wallow away here in the midst of the jungle infested by bees, tigers, a wild tribe called the Bhils, villagers who fear the caves, copying a bunch of pagan images of foreign gods or whatever these images are? Is that what we’re doing?” “Yes,” Fisk said, “that is what we’re doing.” “And Wylie believed he could claim this as some form of ....what? I now understand why you didn’t want to explain our visit until we had talked to Preston.” “Wylie, sir, felt some responsibility for the decay of the art,” Fisk said. “He felt guilty he did not speak up sooner. Pirates and souvenir hunters have already attacked it. I wanted you to see the images and his work. I had hoped that if you saw them....” “Where is your reasoning, Fisk? You didn’t realize that I would find this business ludicrous! You believed that this so-called work would affect me, that we all don’t have better things to do than think about some old caves in the midst of India? Art, my friend, will not win battles. “I'm tired, Fisk. I've made this trip up here for God knows why! I'm sick of India, I'll probably get malaria, I've already got diarrhea, tigers await me in the valley below, I've been stung by I don't know how many bees and other insects, the Bhils probably await again, we had to dodge outlaws and thieves everywhere on the roads, and I'm confronted not with a soldier sworn to duty, but an artist concerned with the work of some dead atheistic monks!” “No journey for vision is wasted, Commander,” Preston said. “As you wish,” White said in an official tone. “But sir, I must advise you, I’m a strategic adviser, and I’m here to evaluate what our role is in all of this. Obviously I know little of art and I’m flabbergasted how the service got involved in this. Now that I have been here, I must say I’m astounded. What strategic advantage could these caves have?” “They’re artistically strategic,” Preston said, “like other ancient cultures could have been, if they were not destroyed by ignorant invaders. We don’t want to be one of those, do we, Commander? Knowledge is advantage.” “What?” White replied, somewhat confused. “Who?” “Preston too feels a certain responsibility,” Fisk intercedes. “He and the villagers cleared away the debris, and he’s trying to preserve the art for posterity.” “So now it is our responsibility to preserve the ancient culture of India, a land that isn't even Christian?” White asked. “Preston is convinced that this work is his destiny,” Fisk said in support, “that he alone has been given the sacred duty of copying the caves, and that he must, well, be part of them in some sense.” “You look like a pathetic sick creature to me,” White responded, “and I'm not sure you're mentally all present. It's damp and dark in here even in daytime. And you’re living like a wild animal. Have you forgotten civilization? And I must agree with the old fellow Sanchi: There’s something eerie about this place!” “Your youth is wasting away, Lieutenant!” White said to Preston. “Come back to us.” “And become important!” Preston scoffed to himself. “And fight wars!” “Commander,” Fisk added, “I don't think he’s in any condition, in any case, to join the forces immediately. He’ll need a couple of months of rehab.” White motioned to Fisk. They moved to an area away from Preston to converse confidentially while Preston continued to paint. “Is this the man you knew?” White asked. “Yes sir,” Fisk answered. “Perhaps he’s mad or going mad,” White said. “This all could make any of us a bit strange.” “Not mad, sir,” Fisk clarified. “Obsessed.” “How long will it be before he finishes the draft of this cave?” White asked. “Two or three weeks perhaps.” “Fine, I will give him a little time, but after that, if he does not return, I’m giving the order to drag him out of here. I will not be responsible for this insanity!” White and Fisk returned to Preston. “Lt. Preston, I order you to report to Madras in eight weeks,” White said, “no more. Good luck and good bye.” White and Preston shook hands. White began to walk out of the cave. “I would like to say a few words to Preston, sir, before I leave,” Fisk said. White acknowledged Fisk and left the cave. “My old friend,” Fisk said, “I know what you’re thinking, but you must finish and return in eight weeks. I don't want to lose you to this tropical madness.” Preston did not respond but continued to paint. “Something stronger than what drew me here must draw me away,” Preston finally said. “How can you stand it, Fisk? What shallowness the fighting machine of civilization creates: Does White see the wonder here, the greatness that lies before his eyes, what these artists endured to create this magnificence?” “White is a soldier,” Fisk said, “groomed for war, as am I. He has his own duty and work. As do I and as do you. We took an oath.” “That is truly your concern?” Preston asked. “Right now, I am concerned about my friend,” Fisk said. “You know that I admire what you are doing, but there comes a time for an end. May I speak personally?” Preston stopped his painting, still holding his brush, and faced Fisk. “Your father and mother asked me to tell you they want you to return,” Fisk said. Preston put down his brush and stared ahead, shaking his head. “Your father said,” Fisk continued, “well, you can imagine what he said. ‘This work is not worthy of a Preston.’ And your mother is just worried. A copy of Robinson Crusoe in the bag is from her, a weird choice, is it not? I’ve tried to assure her, but she’s not stupid.” Fisk gently laid his hand on the Preston’s shoulder. “I'm sorry. I struggled whether I should tell you, but they made me promise. You need to remember that there are others beyond the cave who care about you. We all want you to return after you finish this work here.” Preston nodded and started painting again. “Return? Don't you see, I have returned. I have meaning here.” Again Preston laid his brush on the easel and stood beside Fisk. “Think. What is there for me? That society. Parents whose idea of growth is conformity and achieving what everyone thinks is achievement, who want others to brag about their son, who want guns in the cellar more than paintings in the hall or music in the parlour…” Then he shouted, “I know why they want me back there! “…and teachers who love knowledge more than wisdom, and everywhere, everywhere, a lust for the little bags of shiny coins and stones and power. We all scream: See me, see me, see me, see me. “You know I went to that godforsaken school for my father. I know I did. I went into the army because of my father. Oh, he didn't force me to go, but I went because of him. I didn't marry the woman I wanted because of my father. My mother stood by quietly saying: Oh my, oh my, oh my. “Compare all that to this. Look at this work, Fisk! What did the parents of these artists think? Where were the parents of these artists when they were painting these walls? Do you not think they were proud? Even if they weren’t!” “You'll be more alone than ever now,” Fisk said sadly, “if Sanchi and the villagers live by their word.” “Sculpture breathes life in me, thanks to Sid.” “Sid?” Preston pointed to the giant statue of Siddhartha, the Buddha. “Sid! Trust me, the stone moves, the arms use gestures, the face communicates.” “Part of me wants to stay. If I could, I would share this adventure with you. You know that.” Preston acknowledged him. Fisk indicated the two bags he had brought with him. “Some more books and other items I thought you might like. I brought as big a selection as I could carry. There are also the paints and materials you wanted.” Fisk pulled out a musical instrument. “And your recorder.” Preston suddenly dropped everything and began to rummage through the bag, excitedly looking at the items one by one. “Thank you so much,” Preston said. Fisk approached Preston, Preston stood up and Fisk hugged him. “Good-bye for now,” Fisk said. “I will see you in eight weeks. Remember. Eight weeks.” Preston went back to the bags, his head hidden by the bag. Fisk stared at him and shook his head in concern. “Good-bye.” Fisk waved and left the cave. Preston picked up the bags and brought them to his area in the back in the cave. * The tour guide entered, a small entourage following, the guide talking as she walked. “Now I assume that you have noticed how the styles and techniques of the artists have changed in our tour of different caves. In the early era they paint and sculpt quite simply, with little ornament, almost no symbolism and when there is symbolism, it is the most simple type and with no figures. Indeed in the beginning the Buddha himself never appeared in Buddhist art, and when he did appear, often we see no more than the figure in various gestures, each gesture significant. This accords with the early philosophy of Buddhism, for, we must remember, Buddhism was a reaction or reform movement to Brahmanism, which had elaborate ceremonies and mythology, in which the divine figures were made into dolls. In this sense, in its iconoclastic primitive beginnings, Buddhist art is quite similar--is it not?--to early Christian art, to Muslim art and to Judaic art. However, as the religion grows older, extraordinary complexity also appears, and with it, intricate carvings and paintings of people, Bodhisatvas, animals, plants, and so on, plus, of course, the most complex symbolism. So we see in these caves literally a history of the Buddhist faith from one stage to another.” The tour guide and tourists walked once around the Buddha sculpture and left. * Preston was once again alone and returned to his painting for several hours. As the sky darkened, he placed the fires across the cave entrance and set up the lit stick in the wall. Along the walls have appeared monks in orange robes painting the wall and working on the sculpture of Buddha. Preston waved his hands in the air swatting bees and other insects attacking him. He covered his head with a hat Fisk had brought. Suddenly he jutted forward and ran about the cave, brush in hand, trying to avoid a swarm of bees attacking his head. When it subsided, he returned to his lotus position and spoke to himself, in a grumbling manner, while painting. “With its razor sharp sword of convention lunging at me with the force of centuries, history is the great foe of growth. “Don't you see me working?” Preston spoke to an invisible presence. “Is my cave less a womb than an office or field? Come at me! Strike me, oh friends, family, traditions and customs! The bright lights of me and them descend into the night clay of ignorance and arrogance. Let them mire in the mud of their own thick insecurities, loving their arms and legs and mouths and the tiny things they do with them, locking their potential growth in the traps of recognition and approval.” Preston waited, then shouted: “I hear you!” In a normal volume, he said, “Who can ignore the blaring colours of those hopes and dreams in the forest of opportunity when it is the most trodden trail? “Why am I doing this, you ask, why am I doing this, why am I doing this?” He shouted: “You ask: Why am I alive?” In a normal volume, he spoke: “The stuff of my being stinks from rotting too long in the sun of limited vision.” Preston laughed and looked over at the statue. “You find me repellent, don't you, Sid, you of the full spectrum of colours? I denounce black and white and I am black and white from head to foot. I can fool only fools because the sage cannot know foolishness without being foolish.” There was a loud growl of a tiger. The growl startled Preston, but he returned to his painting. “I have seen the tigers' eyes glistening in the darkness and they have seen mine in the fires of fear, and we discern the same thing: an animal hungry for his food. What gourmets we are, seeing others as no more than a meal, tasting the delightful stupidity in human flesh and drooling for more. Oh, tigers, after you have taken me, romp over and become sated on the battlefields of yonder war, where we, like you, are protecting territory and pride, and are gluttons of property!” Parvati rushed into the cave out of breath. When she did, all of the monks disappeared. She hugged Preston. “Parvati!” Preston said in surprise. “Preston, I had to come,” she said. “I'm really worried. Despite the protests of my father, the villagers are planning to come and seal the entrance to all of the caves! There is even talk of destroying the paintings and sculptures.” “History again,” Preston said to himself. “I cannot stay away from you or the work,” Parvati said. “Like you, I am bewitched by these images and I must disobey my father and the tradition. I too yearn to paint them.” Preston hugged her tightly. “The tigers will not care about your sacrifice, you know that,” Preston said. He held her face gently in his hands. “Danger begins in darkness, sweet Parvati. Our love cannot trick the night.” “I do not care about the tigers,” she said. “I have lived with them my whole life. If that is the will of Allah, then so be it. My dream is to paint like you and become one with these images. Like you, I want to sleep little and paint more.” They heard the sound of voices outside the cave. Parvati ran over to the entrance to the cave and looked out. “They’re here. The villagers are here! What should we do?” Preston shood his head. “I am afraid for you,” Parvati said. Preston walked to her, gently hugged her again, then gave her a brush and sketchbook, pointed to a particular section opposite to the wall on which he is working. Parvati confusedly walked over to the area and began to sketch. The growling of tigers was growing louder and the voices of the villagers diminished until they could no longer be heard. * The tour guide said outside the cave, “Structure is everything. When we examine these works, we must look for form and structure and how colours and lines are used to make the most sensitive expression. These artists had models. They knew what they were doing. Notice the juxtapositions, the intermingling of lights, avoidance of three dimensional thinking and depth perception. See how sculptural the figures are.” The tour guide left. * There was silence until they retired from their work and went to sleep. During the night Preston, laying in the darkness, screamed an incoherent word and then went back to sleep. The sunrise appeared and a bright light shone on the entrance to the cave. Buddhist chanting sounded very quietly in the background. Preston, in the midst of a nightmare, screamed out again in his sleep. Parvati was asleep on another stone ledge near him. Preston turned restlessly and talked to himself, the mumbling grows louder, finally he jumped up, still asleep, and grabbed his gun and faced the entrance. “Stay there! Come no closer!” He swung around, pointed the gun, and shot. The bullet struck one of the paintings. Parvati had now awakened from the gunshot. “I am warning you!” Preston yelled. Preston swung around again in another direction and shot again. Another section of the paintings was damaged. Parvati ran to him and struggled to grab the gun but she failed to stop him, falling backward. She stood up and hit him, trying to wake him up. “Preston, wake up! Wake up! You're dreaming! You're hurting the paintings!” Preston shot again in another direction and again it chipped away at the painting. He reloaded. Parvati tried once more to grab the gun but without success “You will not make war here!” Preston yells. “We are artists! We will not bow to you.” He fired again and pieces of the fresco fell to the floor. Parvati was crying and becoming hysterical. “Stop it, Preston! Stop!” she pleaded with him. Preston fired again and the sculpture was damaged. Finally she succeeded in getting the gun from him and threw it down the cliff. Preston collapsed to the floor. Parvati, still sobbing, dragged him to his bed in a dazed state. “Parvati!” Sanchi shouted from outside the entrance, “you and Preston come down the mountain!” Parvati, startled, jumped up and walked nervously about the cave, not knowing what to do. “Please, Preston, please wake up!” she said, shaking him. Preston slowly awakened. “The villagers,” Parvati said. “They have returned. They are here, with my father.” “Did you hear us?” Sanchi spoke. “We have sealed the other caves and we are going to seal yours. Come out now!” The villagers were beginning to pile rocks and boulders. Parvati and Preston could hear the sound of their work and the rocks smashing up to each other. Preston rose up quickly. “Where's my gun?” he asked “I threw it down the mountain.” She pointed to the paintings. “Look!” she said in tears. Preston saw the damage to the paintings and the sculpture, and rushed from one painting to the other and felt them. “The paintings! What happened? Those devils!” Preston ran to the entrance to the cave. “Never! Never! I’ll never come out,” he screamed to them. “No, Preston,” Parvati said, pulling him near her, “they did not do it. They were not here. There was only the two of us. You had a nightmare and you, with your gun...” “What? I?” he said, shocked by her words. “No! No!” he hollered, hitting his head several times with his hands. He picked up his sketchbook and threw it to the floor. “You were dreaming,” Parvati said gently, holding his hands. Preston started to walk about the cave in great agitation at what he had done. “What kind of beast shoots beauty in his dream, tell me that?” he said. “What dream would kill your dream! What madness brings this madness! Could I not see? Did the colours not enter my eyes? Did my joy not overwhelm my fear?” He brushed his hand gently where the bullets damaged one of the paintings. “How can I repair and overcome what my unconscious will not allow?” Sanchi rushed in and grabbed Parvati’s arm, pulling her from the cave. “Come now!” he said. “They are blocking up the entrance. Only a rat will be able to come and go in a few minutes!” Sanchi looked at Preston. “Will you come or will you die here? Escape Preston, while you can.” Preston did not move and was oblivious to Sanchi and his words. He was transfixed by the damage to the paintings. “Preston!” Parvati cried out. “No, father. I want to stay with Preston. Preston!” Preston, with his back to Sanchi and Parvati, continued to gaze at the sculpture and the damage done to it, running his palm over the damaged area, shaking his head in despair, tears flowing down his cheeks. He began to sob heavily. As Sanchi succeeded in dragging Parvati from the cave and Preston was left alone, the shadow of a tiger appeared on the wall on the other side of the cave, unnoticed by anyone. The sound of large rocks and boulders being piled on top of each other and sealing up the entrance grew softer and softer until it ceased and then too the amount of light slowly leaking through ended. “Preston! Preston!” Parvati’s muffled and desperate words were heard for a time but soon there was only the art sitting in silence and darkness. Preston built a fire and sat in the lotus position reflecting and playing his recorder. The monks reappeared and returned to their work on the statue and paintings. The tiger growled. Its shadow indicated that it moved around the statue and began to come near the fire. It saw Preston, and turned away, but changed its mind, came closer to him, smelled him. Then he laid down next to him by the fire, listening as Preston continued to play the recorder. D.D. Renforth D.D. Renforth: "Cave Man is about the aftermath of the rediscovery of the Ajanta Caves in India. It is a fictional account of the artist who copied the Buddhist frescoes and sculptures and his struggles.. The actual artist is today buried a few miles from the caves. The story is a result of a personal visit to the caves." D. D. Renforth, a graduate of Syracuse University, Duke University, and the University of Toronto (Ph.D.) has three short stories forthcoming in the next months and has published in commercial presses two non-fiction books and several articles, including two articles on art. Renforth taught a course on the interrelationship of the world arts, including the Avant-garde at the University of Toronto. Smooth

(after Nat King Cole’s performance of “Mona Lisa,” by Ray Evans and Jay Livingston) Are you warm, are you real, Mona Lisa? Or just a cold and lonely lovely work of art? He longs to know her gorgeous mystery, desire colluding with near-piety and well-tuned wonder in his serenade to this new “Mona Lisa,” one that’s made of flesh and blood. She’s strangely beautiful, but like the painted girl, unknowable. In vain, he asks her: does she mean to lure a lover? To resist? Or to obscure heartbreak? While her enigma fascinates the singer, it’s his voice that captivates the listener, as note by honeyed note flows with smooth elegance from this man’s throat. We hope his questions never end, his song eluding cadence; we want to prolong this wistful, weightless moment, this confection of word and tone and tenuous affection, a work of art itself. And if the pain that may have motivated his refrain becomes our pleasure, we incur no debt; he sings beyond the shadow of regret, where woe and splendor can be reconciled as smoothly as the Mona Lisa smiled. Jean L. Kreiling Jean L. Kreiling’s first collection of poems, The Truth in Dissonance (Kelsay Books), was published in 2014. Her work has appeared widely in print and online journals, including American Arts Quarterly, Angle, The Evansville Review, Measure, and Mezzo Cammin, and in several anthologies. Kreiling is a past winner of the Great Lakes Commonwealth of Letters Sonnet Contest, the String Poet Prize and the Able Muse Write Prize, and she has been a finalist for the Frost Farm Prize, the Howard Nemerov Sonnet Award, and the Richard Wilbur Poetry Award. relief at Aphrodisias so Britannia this Carian tableau of your subjugation by Claudius the God was a first appearance in sculpture the meekness of the model whose crookèd arms & open breast lack of body armour or rancour predict what time made manifest when Hardy kissed Lord Nelson's cheek the victimhood England expects transcends all stabs of Netflix sex for bronze or marble which at least have the flint of Amazon zeal uphold your pose as murderee Philip Lee The name’s Philip Lee. I’m a scouser (ie a Liverpudlian) of a certain age who has kept the peace in here Turkey for many years now. The Silver Swan

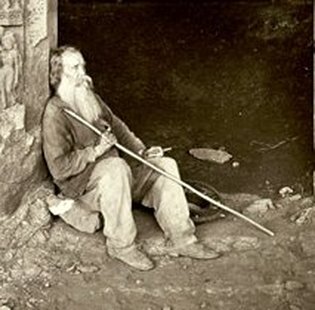

I’ve seen you before wandering the streets, maybe searching for nuggets of your former self, the dad who lulled his little ones to sleep and tucked them safely into a bed of dreams. Many sundowns have passed since then; your beard is straggly, your cap old, crumpled and stained like you, with tales of a traveler’s soul. Your blood-soaked socks stick to your blistered feet; searing pain feels like daggers of defeat. Yet, you trudge through your desert of despair, scavenging like a buzzard through dumpsters for remnants of restaurant feasts. You wearily wend your way through crowded streets seeking a mirage of smiles where people will forget how you look, how you stink and realize you are a carnival mirror, a mere distortion of themselves but for a slip of fate. Your pain is invisible, even laughable to some, but you know it’s fear. You might have laughed, too, if not for losing your job, your home, your hold on the future, now held hostage by a hopeless present, and aware that hostages who aren’t rescued or escape, die. The sky darkens the colour of the devil’s heart and you succumb to your fatigue; fending off fears of drug-hazed thieves and police, and collapse into sleep like a tent missing a pole. You awaken to the shine of a foil-shaped silver swan that smells like the warm home you knew; you crinkle the foil, listen to its crunch and unwrap it slowly, carefully, as if were china. Inside the foil is hot gravy-soaked turkey, buttery mashed potatoes and green beans the colour of spring. Every evening you return to the same place, wake up to a new whiff of the silver swan, stirring senses like the first fresh cup of morning coffee. You don’t know who brought beauty back into your life but soon it is time to move on, your soul too restless to remain in one spot. You gently tuck the crumpled silver swan in your pocket to remind you of someone who didn’t look away. Shelly Blankman Shelly and her husband Jon are empty-nesters who live in Columbia, Maryland with their 4 cat rescues. They have two sons Richard, 31, of New York, and Joshua, 30, of San Antonio. Shelly's first love has always been poetry, although her career has generally followed the path of public relations/journalism. Her poetry has been published by Ekphrastic: writing and art on art and writing as well as Visual Verse, Silver Birch Press,and Verse-Virtual. Grounded

An air vent of a tramp steamer that’s seen better days, it stands on spindly legs -- whimsical, nonchalant. Its colour is mottled yellow, and its attitude is cocky for a thing with one leg stuck in a huge red can. It won’t be pushed around, though — it’s grounded. Bill Waters First published in a book called The Visual in Verse: An Ekphrastic Poets’ Invitational in 2015 by Grounds For Sculpture as a part of their annual ekphrastic poetry contest. Known primarily for his Japanese-style micropoetry, Bill Waters also writes ekphrastic poetry, found verse, book spine poetry, light verse, and all manner of short prose. More of his writing can be found at his blog Bill Waters ~~ Haiku (http://bit.ly/145diBy) and his “blog-within-a-blog” Bill Waters ~~ NOT Haiku (http://bit.ly/1NZSyRo). Bill lives in Pennington, New Jersey, U.S.A., with his wife and three cats. Boxes, Cast of Stillborn Colts and Calves: Sculpture Nicola Constantino: 2000

-after Eduardo Corral This is how the dark sleeps under your feet: boxes, wells, drain pipes rammed with bodies discarded in haste. Contorted bones splayed in a mass grave like a stalk of grape stems. Veiled by a curtain of black sediment. Their bodies: broken branches buried underground. Once, I tossed an armful of sticks into the air: lightning. I thought it was a rustled beehive. How small beasts are angered to kill. Amanda Gomez Amanda Gomez resides in Norfolk, VA where she is a poetry candidate in Old Dominion University's MFA program. Her work is forthcoming in the Eunoia Review. Things That Grow!

How hills writhe and wrench Under Winter All the way down through SpringFall sweet Grown dreamgreen Bluefill, inheld, From Summer! GTimothy Gordon Gordon's seventh poetry/fiction collection, FROM FALLING, will be published Spring, 2016 (Spirit-of-the-Ram P). Work appears in juried journals like AGNI, KANSAS Q, LOUISVILLE R, MISSISSIPPI R, NEW YORK Q, SONORA R, BASEBALL BARD, among others. He has been awarded NEA and NEH Fellowships and been nominated for four Pushcart award and NEA's Western States' Book Awards. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|