|

What is the Artist Trying to Say? Nothing, Magritte Claims

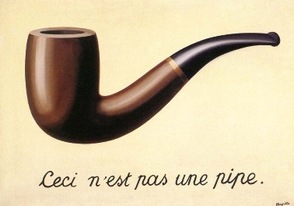

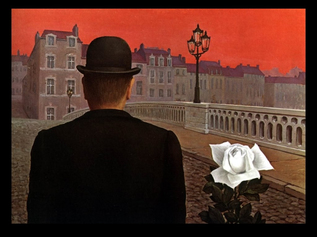

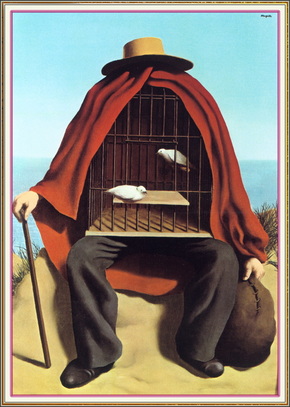

Magritte’s paintings are overflowing with recurring images and eerie objects that we naturally grasp at as symbols. But the artist rejected symbolic interpretation of his work and asked us to avoid deciphering them in this way. "To equate my painting with symbolism, conscious or unconscious, is to ignore its true nature,” he said famously, thus thwarting professional and armchair critics alike from claiming any expertise on what the artist was trying to say. Magritte’s painting, Pandora’s Box, is just begging viewers to try puzzling out what he intended to convey with a blood red sky and a stark white rose. And there’s that man in the bowler hat again, bearing a striking resemblance to the artist himself, even without a face What is this man always looking at, or looking for? One commenter online, oblivious to Magritte’s muzzle against meaning, read the sky as war and the man facing the empty streets as the isolation and loss that haunted the world after WW2. The white rose represented the hope for peace. The rose, the lamppost, the balustrade, the bowler hat. We see particular objects again and again throughout Magritte’s paintings. “…Magritte created enigmatic pictures of flying boulders, burning tubas, giant apples trapped in rooms, or rainstorms of stolid businessmen falling on towns,” writes art historian Camille Paglia. “Typical Magritte paintings show a water glass precariously perched atop an airborne stone balcony.” Magritte plucked the ordinary markers of existence, everyday objects, the humdrum and banal, out of reality and twisted them into scenarios from The Twilight Zone. But he ties our hands behind our backs, refusing to give us an escape route in “figuring it out.” If only we can decode something, if only it’s meaning can be revealed, then we would no longer be snared by our surreal confusion. This of course, is the conundrum of life itself- man’s search for meaning, as they say- but even in saying so, I veer perilously close to symbolism again. Magritte said, “People are quite willing to use objects without looking for any symbolic intention in them, but when they look at paintings, they can't find any use for them. So they hunt around for a meaning to get themselves out of the quandary… They want something secure to hang on to… By asking ‘what does this mean?’ they express a wish that everything be understandable.” Magritte said that viewers “who look for symbolic meanings fail to grasp the inherent poetry and mystery of the image.” He felt that, “No doubt they sense this mystery, but they wish to get rid of it.” I stand forever enchanted in the evocative corridors of Magritte’s imagination, with no need to nail down a particular code. But I do think Magritte’s insistence against interpretation is, like his paintings, something of a mind game. After all, the infamous pipe that wasn’t a pipe was not a pipe because it was a representation of a pipe. You couldn’t smoke it, of course, but nor could you deny that it showed the aesthetic, visual properties of a pipe. It was, therefore, a symbol of a pipe. Literal symbolism in painting traditions often meant stand in signifiers- a dove represented the holy spirit, the snake represented Satan, a rose represented romantic Eros, and so on. So it is understandable that we might wonder whether the painted pipe symbolized an actual pipe, or something else. A particular colleague who smoked a pipe, perhaps, or a penis, if Freud is our guide. Even so, I don’t think most Magritte viewers are looking for literal translations. Magritte may have felt that “reducing” his work to symbols was missing the point, but his continued harping on the viewer’s weakness in longing for meaning was no doubt part of his strategy. His paintings are conundrums, even if they don’t have a specific, correct key to a-ha. When considering his “anti-symbolism,” one must also take into account that Magritte did not like to be called an artist. He was, rather, a thinker who painted. These kinds of curious philosophical mind games reflect Magritte’s droll humour and imaginative genius. His interest in chess and cinematography also make sense in light of the peculiar visual staging and seeming puzzles of his work. Magritte was concerned with mystery and poetry and sought to evoke these through juxtaposition of quotidian objects and scenes. Still, to reject entirely the historical and social context of his artwork would be foolish. He painted through the decades of the ‘20s to the ‘50s, a time where the unconscious played a starring role. Freud’s impact was profound; then, his ideas about dreams, subconscious drives, sexuality, and human nature were tempered (or tampered) by his student, Carl Jung. Both of these brilliant men asked questions and uncovered truths about the human psyche, from the sinister to the sublime. Their approaches differed but ultimately we owe an enormous debt of what we understand about the mind to both of them. These radical shifts in understanding human nature and relating to the world prevailed in the very essence of Surrealism, the ism to which Magritte belonged. And although he was always reluctant to be labeled in any way, the intellectual and social climate of his era and his associations make it impossible that these ideas played no role in his work. Thomas Moore, psychotherapist and philosopher, perhaps expresses the “meaning of Magritte” in his therapeutic worldview that life is not a problem to be solved or fixed. We must live with the paradoxes, for they are integral to our soul. Magritte, he says, “understood more than most that our way of connecting things is not as rational and linear as we imagine.” It is a further irony that Surrealism, the art movement to which Magritte was most closely affiliated, was also in part an heir to the Symbolist movement the century before. Symbolists and Surrealists shared the objective of looking beyond the rational and material for meaning. While recognizing Magritte’s genius for freethinking, I believe it’s also safe to conclude that the painter’s stance against symbolism was a little game of its own, a semantic hustle to make us think and respond more carefully to art by considering our confusion. The best way I can approach Magritte’s art is this: Magritte’s rejection of stand in signifiers- of fixed symbols- cannot mean his audience will not find connection, sublimation, or meaning in his work. A dream dictionary is useless, despite dedicated devotees, and in this way, decoding Magritte according to fixed interpretation is futile. Freud saw a dream about teeth falling out (or a dream about anything else, for that matter) as representing sexual repression. Jung saw anxiety or loss. The theatre of our unconscious is necessarily dependent on our own set of experiences, not just our animal nature. A tooth in one man’s dream is not the same as a tooth in another’s. It could mean pain to a particular person, but even if it recurred, it might now reference instead a memory of a stranger’s smile. The dream dictionary approach to both symbols and to dreams is facile. Meanings are not fixed. Symbols are fluid. Magritte is right that trying to pin these things down is a ludicrous attempt at chipping away from mystery with lousy, primitive, tools and very little in way of imagination or context. But imagery’s very power is the narrative it inspires and the resonance it meets with in its viewer. Magritte’s apple or egg or train or clock may not substitute for particular, intentional alternatives (like “original sin”, “birth,” “speed,” and “time”)-but they will evoke intense and unique associations for different people. “'My images are not substitutes for either sleeping or waking dreams. They do not give us the illusion of escaping from reality. They do not replace the habit of degrading what we see into conventional symbols, old or new…” Be that as it may, only a dead man can approach a Magritte without a whole cascade of illogical, beautiful, eerie, nostalgic, provocative narratives spilling from one’s interior world. Without this effect, there would be no power in the paintings at all. They are compelling precisely because they take us deeper into the profoundly symbolic space of our unconscious. But of course, Magritte knew all of this very well. "The mind loves the unknown," he stated. "It loves images whose meaning is unknown, since the meaning of the mind itself is unknown." Lorette C. Luzajic

2 Comments

mike corbridge

10/3/2020 01:23:58 pm

I loved reading this thank you. I have one question regarding Magritte, that you do not refer to and i am curious to how you did not mention. If Magritte's work is deliberately random and simply meant for the observer to gather and impose their own meaning and narrative. Then why does Magritte choose to repeat and untilise the same motiff over and over again. For example i see the same images in many paintings, images of bells, trees, fires, paper cut outs and bowler hats. These must have symbolism to the artist or at very least become themes within the artists work and therefore must have a utilitarian purpose for the artist and in my theory are loaded with symbolism of the artists life and furthest from the artists subconscious and nearest to a primary essence within the artists mind and formative memory.

Reply

Lorette C. Luzajic

10/4/2020 08:23:32 am

Mike, I wholeheartedly agree with you- even as Magritte tried to dissuade us from thinking this way, Freud might conclude that the unconscious overrides his conscious intentions! We all tend to gravitate toward repeated symbols, motifs that persist in our own narrative. Whether it's a lucky number, a favourite cartoon character, a favourite animal, or the Nike swoosh- there are reasons why we individually and collectively choose or dismiss certain representations. We identify with them. It could signify something religious- a cross or crescent or lotus. It could be a nostalgic symbol of childhood or the kind of corporation or philosophy we espouse- "just do it" etc. Even if Magritte didn't want the world to interpret his work symbolically, he definitely had preferences and used repeat symbols. Eggs, clouds, wine glasses, trains, bowler hats...the list goes on. It is a fascinating body of work.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|