|

I got up for dinner and ate quietly with my parents. They kept up a polite chatter of irrelevant banalities. I don't think I said two words. Then I went back up to my room and stayed there for the rest of the evening. They didn't intrude to say good night. They went to bed around 11:30.

I listened to some classical music on the radio and lay in bed in darkness for a long time. When the station went off the air, I turned the dial until I picked up an extremely weak signal. It was a religious station from somewhere in Virginia. I left it on because of the way it kept fading in and out, which sort of hypnotized me. I didn't actually listen to the words of the sermon, just the absurd, tinny voice against the background of static. My eyes were closed, but I don't think I actually fell asleep. I was more like in a trance of morbid introspection. When I next looked at the clock, it was 3:00 a.m. I turned off the radio. The house was completely quiet. I could hear the air conditioner next door again. I looked out the window and tried to see the stars, but with the street lights and the limited view, it was hard to see them. I put on my slippers and walked as softly as I could downstairs to the basement. I put on the light and looked around. It was the way it had been before Cathy came, except that the table and chairs were unfolded, and a clean, dry cup was on the drainboard. But Cathy had left something behind. It was the print of Van Gogh's Starry Night, which was still taped to the wall above the bed. The sky is a dark greenish blue, the water a royal blue. The town is a rough outline of blue and violet. Its patchy lights are yellow along the shore, and their reflections in the water begin with gold and transform to greenish bronze. The stars above are spiny patches of green and pink. They form the constellation of the Great Bear. In the foreground, on the near bank of the river, are the figures of a man and a woman — lovers — drawn in dark blue- black strokes that blend together. They are alone on a starry night in a setting of ideal tranquility, sharing a moment of sublime and inexpressible happiness. by Crad Kilodney, an excerpt from the novella Cathy, 1985

0 Comments

Rock insults us, hard and so boldly browed

Its scorn needs not to focus, and with fists Which still unstirring strike: Collected it resists Until its buried glare begets a like Anger in us, and finds our hardness. Proud, Then, and armed, and with a patient rage We carve cliff, shear stone to blocks, And down to the the image of man Batter and shape the rock's Fierce composure, closing its veins within That outside man, itself its captive cage. So we can baffle rock, and in our will Can clothe and keep it. But if our will, though locked In stone it clutches, change, Then are we much worse mocked Than cliffs can do: then we ourselves are strange To what we were, which lowers on us still. High in the air those habitants of stone Look heavenward, lean to a thought, or stride Toward some concluded war, While we on every side, Random as shells the sea drops down ashore, Are walking, walking, many and alone. What stony shape could hold us now, what hard Bent can we bulk in air, where shall our feet Come to a common stand? Follow along this street (Where rock recovers carven eye and hand), Open the gate, and cross the narrow yard And look where Giacometti in a room Dim as a cave of the sea, has built the man We are, and made him walk: Towering like a thin Coral, out of a reef of plaster chalk, This is the single form we can assume. We are this man unspeakably alone Yet stripped of the singular utterly, shaved and scraped Of all but being there, Whose fullness is escaped Like a burst balloon's: no nakedness so bare As flesh gone in inquiring of the bone. He is pruned of every gesture, saving only The habit of coming and going. Every pace Shuffles a million feet. The faces in this face Are all forgotten faces of the street Gathered to one anonymous and lonely. No prince and no Leviathan, he is made Of infinite farewells. O never more Diminished, nonetheless Embodied here, we are This starless walker, one who cannot guess His will, his keel his nose's bony blade. And volumes hover round like future shades This least of man, in whom we join and take A pilgrim's step behind, And in whose guise we make Our grim departures now, walking to find What railleries of rock, what palisades? by Richard Wilbur, 1950 Why I Am Not a Painter

I am not a painter, I am a poet. Why? I think I would rather be a painter, but I am not. Well, for instance, Mike Goldberg is starting a painting. I drop in. "Sit down and have a drink" he says. I drink; we drink. I look up. "You have SARDINES in it." "Yes, it needed something there." "Oh." I go and the days go by and I drop in again. The painting is going on, and I go, and the days go by. I drop in. The painting is finished. "Where's SARDINES?" All that's left is just letters, "It was too much," Mike says. But me? One day I am thinking of a color: orange. I write a line about orange. Pretty soon it is a whole page of words, not lines. Then another page. There should be so much more, not of orange, of words, of how terrible orange is and life. Days go by. It is even in prose, I am a real poet. My poem is finished and I haven't mentioned orange yet. It's twelve poems, I call it ORANGES. And one day in a gallery I see Mike's painting, called SARDINES. Frank O'Hara, 1956 The Great Figure

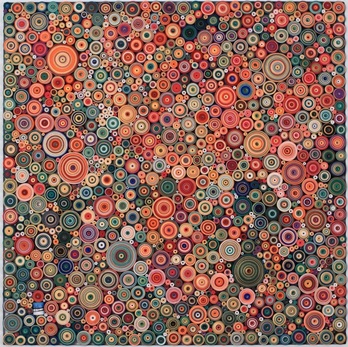

Among the rain and lights I saw the figure 5 in gold on a red firetruck moving tense unheeded to gong clangs siren howls and wheels rumbling through the dark city. William Carlos Williams This stunning work by Hadieh Shafie, called 11580 Pages, is made with acrylic paint, ink and countless handmade paper scrolls containing handwritten words of love in the Farsi language.

|

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|