|

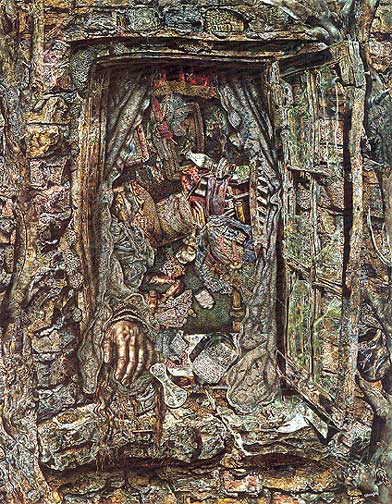

Ivan Albright, to Whom I Keep Returning Ivan Albright, 1897- 1983, was primarily a painter, but he also kept detailed journals of his work and wrote poetry as well. His work appalled many and fascinated many more. He wasn’t interested in conveying familiar forms or notions of beauty. A lengthy essay on Albright by Courtney Graham Donnell begins with a poem of the artist (after which the essay takes its title) in which Albright reports: “A painter am I / Of all things / An artist who sees / the door and chair / And sees on the smooth things a flaw there / and sees on the round things a hollow there / And colors are not just colors to him…” Later in the same essay, Donnell quotes Albright revealing: “If I stir, [objects] stir. If I stand arrested, they become motionless.” These two fragments from the artist begin to unlock why I find Albright’s work so compelling. I first saw Albright’s work live at the Chicago Art Museum when I was a teenager. I remember being unwilling to move from his painting That Which I Should Have Done I Did Not Do (The Door). The painting enthralled me on multiple levels. First, the title intrigued me. I wasn’t used to artists who did more than hint at what their work was about or even distract from it through their titles. Albright’s titles tell part of the story of the work. (Of course, not wholly—he is an artist, and understands that the viewer/reader must also be allowed space to feel about the work. There must be enough loose threads that someone outside the work can pick up and tie to their own experiences.) His works bear names such as: Wherefore Now Ariseth the Illusion of a Third Dimension; And Man Created God in His Own Image (Room 203); Poor Room—There is No Time, No End, No Today, No Yesterday, No Tomorrow, Only the Forever, and Forever and Forever without End (The Window); Heavy the Oar to Him Who Is Tired, Heavy the Coat, Heavy the Sea. As an incipient poet, I was fascinated that a painting title could read as a compact story or poem. Next, the dates given for the painting, 1931-41, struck me. The artist took a decade to complete a single canvas. More than inspiration, that suggested obsession. This was an artist who was compelled to visit and revisit his work, to tell different parts of the same story, to approach it from all angles. Indeed, Albright has noted that he wanted to convey the way light “fragmented” his subjects as it hit them from all sides. For many of his pieces, Albright built three-dimensional mock-ups in his studio so he could circle around them, enabling him to add details to his paintings for years longer than any human subject would be willing to sit. This leads to the most compelling aspect of Albright’s work for me as a young person. His depictions were both arresting and horrifying—almost grotesque in their strangeness. Teens are learning that much about adult life contains just that mix of fascinating and frightful. They are acutely alert to ways in which surfaces misrepresent. They are still heavily undergoing socialization, that great falsehood in which they are told to act politely and strive for certain socially-permissible goals, while underneath, they know that what drives humans are baser, uglier, more selfish instincts. They are new to their sexualized bodies, which fascinate but also horrify. They are self-conscious about their hair, their skin, their symmetry (or lack thereof). Ivan Albright’s canvases showed that surface is an illusion, clean beauty is an illusion. He understood the multiplicity within us. He wasn’t afraid to look at ugliness and make it beautiful without hiding it or glossing it over. In fact, imperfection was the source of his inspiration. I was hooked. Albright tells writer Katherine Kuh, “For some time now I haven’t painted pictures, per se. I make statements, ask questions, search for principles. The paint and brushes are but mere extensions of myself or scalpels if you wish.” This claim resonates with me, now a poet in my own right, all grown up. My poems are extensions of myself—statements, questions, and investigations of principles. They are about the process as much as the product. Ivan Albright’s work inspires Ekphrastic poetry because it asks for multiple visits, begs multiple interpretations. Even reporting what the painter is doing is an elusive project. For example, when he paints wealthy art collector Mary Block (Portrait of Mary Block), is he celebrating her or gently mocking her? He conveys her strength of character, her wealth, and her command, at the same time that he makes her look menacing and ghoulish. Similarly, in his self-portraits, (specifically those from 1934-5), he places himself among desirable things in elegant clothes, yet manages to make himself look dissipated, like someone coming apart at the seams. The body of young female model in Three Love Birds has a youthful face while at the same time welling and bursting with the kind of bubbling accretions we associate with middle and old-age. All of this dissonance begs for a poetic response. Too, I appreciate Albright’s desire to separate himself from movements and labels. He was unafraid to be other, a “voice” of one for an audience of one. Susan Weininger’s essay, “Ivan Albright in Context,” quotes him thus: “To join some general movement in art …is to join a buffalo stampede. I say, let the artist be the hunter rather than the buffalo.” As someone who dropped out of an MFA program because of distaste for how Academia seemed to demand a particular voice and produce an aesthetic in almost cookie-cutter fashion, I embrace this independence of spirit. Similarly, in this internet age with its plethora of literary journals, it’s not clear if anyone at all is reading our poetry except for the editors who selected it and the poets who wrote it. One has to write primarily for oneself, interrogating existence out of a private and obsessive motivation. Finally, Albright models how I want to die. Four days before his own death, he created his final self-portrait (Self-Portrait 1983), a shaky line-drawing of his eyes, later made into an etching by John Paulus Semple. The body has all but gone, the life forced out of it, but the artist as witness, the vision of Albright’s singular intelligence, remain to the very end. That is what I hope for, to comment on my experiences until the biochemical mystery that makes me who I am ceases. Thus, I offer Ivan Albright as a source of inspiration to all who read this. One can visit and revisit his works endlessly without exhausting their narratives. Each canvas contains a world and its stories, whether depicting the animate or the inanimate. Nothing is as it seems. Paraphrasing Albright, every time we stir ourselves to examine them, the canvases come to life. One suspects that even after we turn our backs, they go on living and speaking—if only to themselves. Devon Balwit (All quotations and images referenced from Ivan Albright: Magic Realist, The Art Institute of Chicago, 1997) Devon Balwit is a poet and educator from Portland, Oregon, who learned to love art from her artist parents. Her poetry has appeared in numerous journals, among them: 3 elements, 13 Myna Birds, Anti-Heroin Chic, Dream Fever Magazine, Dying Dahlia Review, Emerge Literary Journal, Free State Review, MAW, Rat's Ass Review, Rattle, Red Paint Hill Publishing, Referential, Serving House Journal, The Cape Rock, The Literary Nest, The Yellow Chair, Timberline Review, vox poetica, and Vanilla Sex Magazine. She welcomes contact from her readers.

2 Comments

Hope Palmer

10/29/2016 10:27:26 am

a sensitive and illuminating response to an artist's work that ignites wonder from the first moment of viewing

Reply

Nwankwo Prosper

1/15/2020 07:57:57 pm

This motioned deep the motionless. How art illuminates a world and its grotesque perfection in tales. I'm fortunate to have read your insightful muse. It's clear, poetry is a language of arts, to the demystification of the hereafter.

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|