|

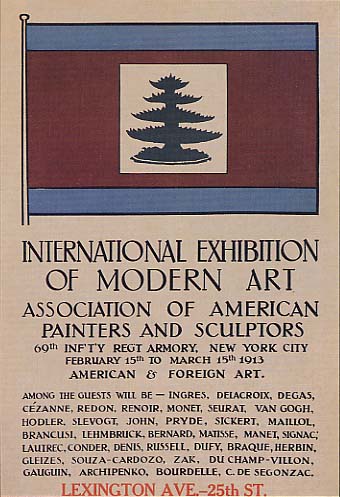

William Carlos Williams: A Journey Into Art ‘The real innovations in art and in life, whether in literature or painting, depend on the manner in which the elements of one medium are translated to the conditions of another.’ Bram Dijkstra Several years ago, I attended an exhibition of the collected works of Kasimir Malevich in the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam. What struck me as I moved from room to room was that, in this astonishingly diverse one-man-show, I was witnessing the very development of modern art. It also occurred to me at the time that Malevich’s wide embrace of the emerging styles within modernism had much in common with the ekphrastic poetry of William Carlos Williams (1883-1963), a poet whose close involvement with the visual arts resulted in many successful attempts to break through the boundaries of his own medium (as Dijkstra expresses it). Indeed, as we move, so to speak, from poem to poem, we find the influence of many diverse modernist styles reflected there, and the sheer variety of these texts suggests that Williams was exploring his aesthetic milieu with the same intensity that Malevich explored his. In this essay, I trace Williams’ whole-hearted embrace of the world of art that altered the very nature of his poetry and, as in Malevich’s paintings, reflect the developments in the visual arts themselves. From Keats to Picasso ‘undying accents repeated till the ear and the eye lie down together in the same bed’. (‘Song’, 1962) Written at the end of his life, these lines from ‘Song’ offer a witty self-retrospective on Williams' continual engagement with the visual arts. His choice of a biblical allusion here suggests the unlikely joining of two seemingly incompatible entities: the visual and the verbal arts and the boundaries that divide them. These lines are also the poet’s final signature to an entire body of work in which the visual arts play a central role, much of the poetry illustrating Williams' conviction that ‘to bypass the eye, you bypass the mind’. It’s not surprising that Williams focuses on the sense of sight in his verse, as his first artistic efforts were not in writing but in painting. As he states in his preface to Selected Essays, ‘I almost became a painter, as had my mother been before me, and had it not been that it was easier to transport a manuscript than a wet canvas, the balance might have been tilted the other way.’ Of course, Williams was not the only poet/painter of his generation, nor was he alone in integrating elements belonging to the visual arts into his poetry. Yet his inter-art experiments were far more diverse and had more far-reaching consequences than those of his contemporaries, and the poems which grew from these ventures into the visual arts were to have a profound impact on the development of American poetry. New Beginnings Williams’ understanding of the ‘undying accents’ in his poetry as an equal fusion of the visual and verbal were the product of a long poetic journey, one that reflects the unfolding history of the visual arts in the first half of the 20th century. But his first poems (published in Poems 1909, and The Tempers, 1913), do not carry any suggestion of the impact that the visual arts would soon have on his poetry. These early poems, in fact, were quite different from the sharply-focussed and clean-edged verse for which Williams is best known. His 1909 poem ’First Praise’ is a good example of how little these poems carry Williams’ later conviction that poetic language must have a direct and unadorned relationship with its object: Lady of dusk-wood fastnesses Thou art my Lady I have known the crisp, splintering leaf-tread with thee on before White, slender through green saplings; I have lain by thee on the brown forest floor Beside thee, my Lady. Lady of rivers strewn with stones, Only thou art my Lady Where thousand the freshets are crowded like peasant to a fair Clear-skinned, wild from seclusion, They jostle white-armed down the tent-bordered thoroughfare Praising my Lady. These studiously romantic lines were written as an occasional poem recalling a visit to Williams’ girlfriend Flossie and her family at their summer home in Cooks Falls, New York. Aside from its excessive sentiment in view of the occasion, the poem does not yet suggest Williams’ later drive toward minimalism, which was soon to do away with what he called ‘stock responses, overripe images and the decayed rhythms of the language’. Williams himself looked back on poems like this one with dismay at their ‘falseness’ and the fact that ‘I knew nothing of language except what I’d heard in Keats or the Pre-Raphaelite brotherhood’. Yet by the time Williams had written ‘The Arrival’ in 1915, it is clear that he had not only rejected the language of his earlier poems but presented even the objects of his devotion from a perspective unclouded by romantic idealism: And yet one arrives somehow, finds himself loosening the hooks of her dress in a strange bedroom Feels the autumn dropping its silk and linen leaves about her ankles. The tawdry veined body emerges twisted upon itself like a winter wind. The difference between these two poems suggests that a remarkable development had taken place in Williams’ approach to his verse. Indeed, ‘First Praise’, with its focus on idealised beauty, prevents any concrete perception of the lady herself; but in ‘The Arrival’, a more realistic image of beauty emerges - one that lies outside the tradition of the love lyric and other poetic norms. But more than this, we also find here a significant deviation from the conventional idea of poetic subject matter: a ‘tawdry, veined body, is quite unlike the kind of beauty that inspires the praise of a ‘thousand freshets’. Although this later poem is still far removed from the form Williams’ poetry was to take, its engagement with the object (which at this point has as much to do with the ‘Objectivist’ movement as it has with the visual arts) is still far more direct than the distancing panegyric of ‘First Praise’. Williams’ drive toward minimalism eventually produced poems like ‘This is just to say’, a husband’s loving apology to his wife: This is just to say I have eaten the plums that were in the icebox and which you were probably saving for breakfast Forgive me they were delicious so sweet and so cold. So what happened in these intervening years that would have had such a pronounced impact on the structure and focus of Williams’ verse? The Armory Show of 1913 happened. The Armory Show Officially known as the ‘Exhibition of Modern Art at the 69th Regiment Armory on East 25th Street’, the show was launched by the avant-garde Association of American Painters and Sculptors, which famously exhibited (among other art styles) modernist 20th century works by Picasso, Georges Braque, Paul Cezanne, Henri Matisse, Wassily Kandinsky, Ferdinand Leger, Andre Derain, Maurice de Vlaminck, Marcel Duchamp, Constantin Brancusi and Alexander Archipenko. Modernist art embraced a number of radical movements such as Fauvism, Cubism, Futurism and others, and their common goal was to move away from realism and representationalism toward abstract art. This move was to prove highly challenging for many of the American public, who were used to realism and confused by abstraction. (For a short BBC video on the Armory Show and its impact, see: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qJWLoXziXC4.) One member of the American public who was not distressed by the new abstract art was Williams, who was beginning to find his own poetic voice during this period, a period which had already witnessed considerable innovation and cross-fertilisation among the arts; in fact, the Armory Show was the single most important event that was to have far-reaching consequences for Williams. This exhibition, which was, according to John Hartz, ‘the most significant, improbable and iconoclastic art exhibit ever presented in America’, was organised to promote new developments in American art and with the Armory Show they intended to mark, as Walt Kuhn writes, ‘a starting point of the new spirit in art …and make the big wheel turn over in both hemispheres.’ This ‘new spirit in art’ was not lost on Williams, who immediately understood its implications for his own poetic art. As he explains in a 1963 essay: 'In Paris, painters from Cezanne to Pissarro had been painting their revolutionary canvases for fifty or more years, but it was not until I clapped my eyes on Marcel Duchamp’s Nude Descending a Staircase that I burst out laughing from the relief it brought me! I felt as if an enormous weight had been lifted from my spirit for which I was infinitely grateful.” The enormous weight was the ‘encumbrance of traditional poetics and the dominance of the academies’. What was most attractive about the new forms which he saw at the Amory Show was that they suggested a more direct means of recording experience. For Williams, this meant the discarding of metaphor - or, in. his own words, ‘all the pretty glass balls’ - in favour of a direct engagement with the object and ‘one clear moment of perception’. Williams underlines the importance of this decision, when he writes: ‘The coining of similes is a pastime of very low order …much more keen is that power which discovers in things those inimitable particles of dissimilarity to all other things’. This stress on paying attention to separate elements, or ‘particles’ of objects rather than on their similarity to other objects (ie, metaphor), can be seen in his poem ‘To a Solitary Disciple’ (1916). Here, he begins by directing the writer (and reader) to notice how the moon is ‘tilted above/the point of the steeple/than that its colour is shell-pink …’ and to ‘…observe that it is early morning’ rather than that ‘the sky is smooth as a turquoise.’ Most significantly, the rest of the poem is informed by the important innovations that Williams discovered at the Armory Show, specifically those of cubism: Rather grasp How the dark converging lines of the steeple meet at the pinnacle - Perceive how its little ornament tries to stop them - See how it fails! see how the converging lines of the hexagonal spire escape upward - receding, dividing! sepals that guard and contain the flower! This poem bears witness to the fact that in a very short time following the publication of ‘The Arrival’, Williams was concentrating on a specifically pictorial approach to poetic form. The careful attention to the geometrical nature of the object, such as references to the ‘division’ of the ‘converging lines of the hexagonal spire’ - are a direct borrowing from both cubism and futurism. It is clear that, following the Armory Show, Williams’ verse began to give evidence of an entirely new way of looking at objects. ‘Seeing’, for Williams, (as Peter Halter has pointed out in The Revolution in the Visual Arts and the Poetry of William Carlos Williams) is ‘to perceive and feel the visual dynamics inherent in all forms and colours, and to assess the dynamic patterns that result from their interaction…an interaction which imitates the movement that flows through any work of art’. Williams did not regard his attempt at ‘seeing’ as a solitary venture: the reader of this poem is repeatedly asked to ‘grasp’, to ‘perceive’ and to ‘see’, and becomes as much the viewer of an object as the reader of a poem. Williams went on to experiment with many modernist art movements during this period, and one need only notice the dates of publication of these poems to comprehend the intensely exploratory nature of his ekphrastic poetry. These poems (most of which were published in Spring and All, 1922) truly reflect the energy and diversity within the world of the visual arts during the first years of the 20th century. It is important to note that various movements in the visual arts and literary arts did not (and do not) develop in isolation, and the modernist period witnessed a substantial overlap between the arts and their ideologies. It is not surprising that these are reflected in Williams’ ekphrastic use of paintings and their various styles. As Paul Mariani points out in his biography of Williams A New World Naked, ‘art, like baseball and medicine, was for Williams very much a team effort.’ That Williams saw poetry as an integral part of the art ‘team’ is evident throughout his verse and these are the innovations that helped ‘turn the big wheel in both hemispheres’ in art and in literature. Valerie Robillard Valerie Robillard was a lecturer in English Literature at the University of Groningen, The Netherlands (now retired). She is the author of The Ekphrastic Moment in the Poetry of William Carlos Williams (1999) and her website on ekphrasis (‘Poems Meet Paintings’) can be found here.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|