|

Photograph Where I am Permed And now I am permed, and it is not flattering. My smile is only a half-smile. Someone (my mother didn’t drive) took me to Dallie’s where the smell of the permanent solution was awful. I’m about eight, and holding my Easter basket. My dress is lovely with a wide, frilly collar. Mom dressed me as she dressed herself—inexpensively, but with style. I’m next to my grandmother whose name is Hazel, and she’d holding my half-sister, Sherry. Granny is in a sleeveless dress with buttons all the way down the front. She looks as if the sun is in her eyes, and isn’t smiling. I could read a lot into that for we are in Landrum, S.C. where my jealous step-grandmother lives. She was never nice to us. My stepfather’s back is to the camera, and he’s looking down as if searching for something. His brother Elford is doing the same. Elford is the favorite son, and nothing my stepfather did ever changed that. They are both in their army uniforms. Grandpa Pruitt is nearby, but you only can only see a bit of him. He was meaner than my step-grandmother, maybe because of her, or his drinking. We could have all been to church. I loved Easter and couldn’t wait to tear off the cellophane of my basket, and eat the candy. The Pruitt’s called my mother May-ree, taking the loveliness right out of her name. There was little for me to do there except pick muscadines and gather eggs from the hens, shooing away the mean rooster. During rain, I would sting buttons on thread. The Singer machine sat near the kitchen window, but I didn’t know how to sew. I got bored once, and cut down a tree to play Christmas. My step-grandparents didn’t own the land, and my mother punished me. Out back there was a pile of Tub Rose snuff cans since Granny Pruitt dipped snuff. I could smell her breath, and see how brown her teeth were. Yet, smoking was considered a sin: my mother was sinning. Granny P could make good fried pies but seemed to resent you eating them. I longed to return to Radford where my Grandmother and Poppie lived. My granny would comfort me, and shoo away night fears, and let me lie in her bed after Poppie had gone to work. We’d make up stories, pretending to travel to far-off places. Never mind we could actually go only to where gas money took us, often to West Virginia to visit family. I’d get sick riding around those curves with the big drop-offs. For now, I was stuck in Landrum trying to comb out the curls. My hair looked like a head of cabbage. Vanity would come easy for me with such competition from my mother’s beauty. Sherry was the one who looked more like her, and she too had a lovely name. Gail was like a stone you couldn’t budge. Each day seemed forever, and the candy would get eaten, and the dyed eggs begin to smell. I knew we’d soon leave, and couldn’t wait to get in the car, and drive down that dirt road. Road I ran on breathlessly as if something were chasing me and closing in. Gail Peck Gail Peck is the author of eight books of poetry. Her first full-length, Drop Zone, won the Texas Review Breakthrough Contest; The Braided Light won the Leana Shull Contest for 2015. Other collections are Thirst, Counting the Lost, From Terezin, Foreshadow, and New River which won the Harperprints Award. Poems and essays have appeared in Southern Review, Nimrod, Greensboro Review, Brevity, Connotation Press, Comstock, Stone Voices, and elsewhere. Her poems have been nominated for a Pushcart, and her essay “Child Waiting” was cited as a notable for Best American Essays, 2013.

0 Comments

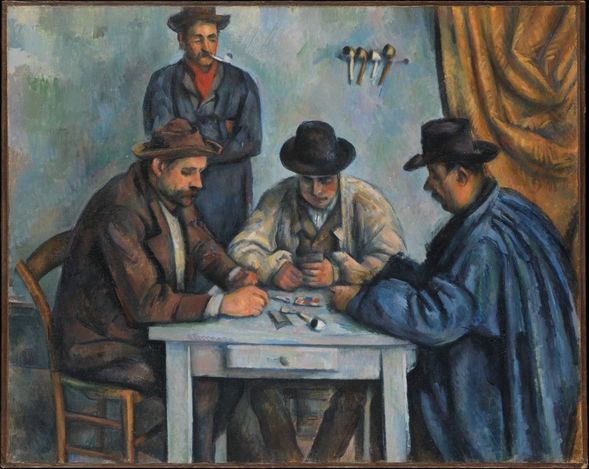

The Card Players A ledger kept in a drawer too long, it all begins to unravel between Pierre and Claude with discreet card games, unpaid promises, deals, and unsettled scores. Winter hangs over the poker table as Claude, a big man with a bigger debt arrives dressed in a tan overcoat and new black top hat, sits down on a wooden chair, back to the wall. Across the table, Paul and Charles lean in to their cards. When Paul ups the ante, Claude’s grin seems almost jovial. Indeed, his cheeks display a healthy shade of blush as he contemplates his cards, shuffles slightly in his chair, then arranges them by suit. But though he holds his cards steady, Claude’s hands feel cold and damp. Paul, on Claude’s right, wears an ordinary brown coat and hat. A former friend of Claude’s perhaps; now Claude owes him money. Like a frayed wire ready to short, Paul displays brusque ways. A lively man, Paul, though today, his sober grin might mislead you. Charles plays on Claude’s left, aloof. Dressed in an over-sized blue coat, and a possible acquaintance of Paul, Charles lays his pipe down on the card table, focuses on his hand. Drawn in by high stakes, the three forget Pierre until they hear him shuffle. Accustomed to his own way, Pierre, a shrewd man with a pointy chin, wears an orange scarf, black coat, and brown hat. A white pipe pursed between the lips of his poker face, and arms folded, Pierre seems removed though he looks on, as he calculates the odds. To witness the luck of the draw, Pierre waits transfixed against the cold, grey wall, perched over Claude’s hunched shoulders, as the four count on the night to play itself out. Pierre plants himself against Claude’s wishes, in the perfect spot to peer at Claude’s hand, as they hedge their bets. Pierre wants his money, he tastes it, as he watches Claude’s cards. If Claude takes all, Pierre wins the jackpot. Though silent, through his presence in the room, Pierre asserts control. Pierre designs to take Claude’s life, should he lose again tonight. As Claude plays his last game, Cezanne enters the room, unobserved. Since he shows up too late to draw cards, Cezanne paints the scene instead. Michele Harvey Michele Harvey’s poems have appeared in several literary publications including: Vine Leaves Literary Journal, Progenitor, Copper Nickel and The Litchfield Review. Her sonnet, “Dinosaur Ridge,” is the focal point for a permanent art in public places display at the Jefferson County Government Center railway station in Golden, Colorado. Michele Harvey is the author of Poetry for Living an Inspired Life. Holy Beard,

Harden transfixed, crowd agape, fingers pointing. Sometimes greatness falls upon us. We bear its weight, bruise even, extricating ourselves, even as we try not to miss the moment. O rise! O pitch the air-filled world up and through, up the tally, make it / us / all meaningful! (Some pay no attention, wouldn’t trouble themselves to slide a finger into the bloody rent. We won’t concern ourselves with such as these, we who believe.) Devon Balwit This poem was inspired by a viral sports photo by Carlos Gonzalez, which was then compared to Raphael's artwork above, and other ancient paintings. Click here to see the photo and the story. Devon Balwit writes in Portland, OR. She has five chapbooks out or forthcoming: How the Blessed Travel (Maverick Duck Press); Forms Most Marvelous (dancing girl press); In Front of the Elements(Grey Borders Books), Where You Were Going Never Was (Grey Borders Books); and The Bow Must Bear the Brunt (Red Flag Poetry). More of her individual poems can be found here as well as in The Cincinnati Review, The Stillwater Review, Red Earth Review, The Inflectionist; Glass: A Journal of Poetry; Noble Gas Quarterly; Muse A/Journal, and more. Women Picking Olives, 1889

The oil that is extracted here from the most beautiful olives in the world replaces butter. I had great misgivings about this substitution. But I have tasted it in sauces and, truthfully, there is nothing better. Jean Racine, “Lettres d’Uzès, 1661” And there’s nothing better than old friends; no substitutes will do. These women in their plain coloured dresses remind me of what I’ve lost, the friends who are not here. There’s nothing rational about this, why a woman on a ladder, another reaching into the trees, a third with a pannier would speak to me of loss, but there are spaces between the branches where the dove-coloured sky bleeds through, and the path through the orchard runs like a river, liquid brush strokes of clay, the field ochre on both sides. The dead no longer need to feed the body, decide between oil and butter for their bread. They can slip between the next world and ours if they want to, on the breath of the wind. There’s a ladder in this painting, but it doesn’t reach to heaven. Instead, it’s the divide, the uncrossable bridge, the message still on the answering machine. Above the orchard, the sky is full of ashes of roses: parentheses, ellipses, things we hold onto, even as they slip away. Barbara Crooker This poem was first published in Barbara Crooker's book, Les Fauves (C&R Press, 2017). Barbara Crooker is the author of eight books of poetry; Les Fauves (C&R Press, 2017) is the most recent. Her work has appeared in many anthologies, including The Poetry of Presence and Nasty Women: An Unapologetic Anthology of Subversive Verse, and she has received a number of awards, including the WB Yeats Society of New York Award, the Thomas Merton Poetry of the Sacred Award, and three Pennsylvania Council on the Arts Creative Writing Fellowships. Her website is www.barbaracrooker.com Nude Descending a Staircase Moonstoned in the depths of the Ambien hours, she flows—bedroom to kitchen to bath—naked, gravity-lover downstairs dancing, unembarrassed as whitewater in a kayaker's dream. Sleek and dangerous, she hypnotizes: my Salome, my mistress of hydrodynamics and dance. Swamped in veils, in waves and brush strokes, oh what can I do but founder: twee playboat capsized in her aftermath, shouting out, not waving, but drowning! O shapeshifter, sharpshooting mad under moon, descend untouched, untouchable, slip aqueous through my luckless grasp—liquidshimmery, lickety- split—reflections tongueing lovers lost in new ideas of what is face, what is form where current is king. No mudpuddle Narcissus, I only have eyes for the rushing by, the burning too quick for retina to register, for beauty in fleetest form setting the millworks afire, out beyond the rainglossed highway, where muscle cars whoosh puddles into oilslicked masterpieces, streetlit abstract expressions: four hundred horses of paintbrush, one hundred thousand Duchamps dancing on the head of a pin. Ah, the hunger in your eyes, the shiny fish writhing under your skin! Shiver me your undulation, modulation, your ballet, your hipsway, your come-thee-hither from upstairs down. For you I breathe deep, dive deep into your sizzle and froth, scream you a song you carry only to lose to a bigger river. Another voice in the drowned-boy chorus, another lullabye gone home to sleep in the sea. Brent Terry Brent Terry holds an MFA from Bennington College. He is the author of three collections of poetry: the chapbook yesnomaybe, (Main Street Rag, 2002) the full-length Wicked, Excellently (Custom Words, 2007) and Troubadour Logic (Main Street Rag, forthcoming 2018). His stories, essays, reviews and poems have appeared in many journals. He is working on new poems, a collection of essays and a novel. Terry lives in Willimantic, CT, where he scandalizes the local deer population with the brazen skimpiness of his running attire. He teaches at Eastern Connecticut State University, but yearns to rescue a border collie and return to his ancestral homeland of the Rocky Mountain West. La Chascona

The light is Pisco brandy aged in an oak barrel on the backstreets of Bellavista. A flute of champagne fizzes on a mosaic tile. She perches on a Fornasetti stool in the Summer Bar, her long legs crossed waiting for hora del coctel. Her hair is unruly red, curled like the paths that lead to secret portholes, incognito nooks. A gift – lapis lazuli necklace nestles against her breasts. Her tremulous face gazes out, eyebrows arched, lips pursed as if ready to sing a Sonato to the gilded mountains, while he remains silent like an hidalgo on a coat of arms. Jane Salmons Poet's note: La Chascona means wild-haired woman in Spanish. It is also the name of the house Pablo Neruda built for his lover Matilde Urrutia. Jane Salmons is a teacher living and working in Stourbridge in England. She is currently studying an MA in Creative Writing and has had poems published in various online magazines including ‘Ink, Sweat and Tears’ and ‘Algebra of Owls’. Aside from writing poetry, in her precious free time she enjoys photography and creating handmade photomontage collage. Unfurling Pieter Breugel's The Triumph of Death

Now I see! it is a scroll being wound to the right into the maw of time. Humanity vanishes as flamboyant and noisy as ever, and as surprised as ever, mouths shaped into fleshy Os of astonishment. Who? me? There must be a mistake! Bonier others look on, grinning in delight, for which their teeth alone seem to suffice. In the next panel, the one you cannot see yet, the skies are blue, the animals have returned to reclaim the land. Even the horse, rawboned and beaten, that pulled death's cart has fattened up. It looks up from the grass and shakes its noble head as if to dispel the last remnants of a foul dream. But for now, it's a party! Everyone has come bringing their instruments, the big bells trumpets strings timpani and something that looks like a tambourine, or is that a cartwheel? Far off, the sea boils and fire falls from the air. And crosses everywhere! Sign beneath which Netherlander and Aztec alike perished. On the left, a young disconsolate (or aging philosopher — it's hard to tell) stares into his hand or what is left of it. He sees the future dawn without his kind and knows it's right, they've made a hash of things. And nothing, nothing to be done but wait until the final turn grinds him to dust. Michele Stepto Michele Stepto lives in Connecticut, where she has taught literature and writing at Yale University for many years. In the summers, she teaches at the Bread Loaf School of English in Vermont. Her stories have appeared in NatureWriting, Mirror Dance Fantasy and Lacuna Journal. She is the translator, along with her son Gabriel, of Lieutenant Nun: Memoir of a Basque Transvestite in the New World. Becoming Leonardo

In the Annunciation, I see Gabriel as suitor: features of Florentine youth, curls of a dandy, a lily to present to the beauty. He is on one knee. The young woman, non-plussed, never expects such impetuousness from someone she remembers from the crush near the Duomo. The miracle is her hand holding her place over the open Tanach. Tapered fingers, sensuous, extension of draped, transparent veil, pedestal. Near her, architecture of stone remembered from the Palazzo Vecchio. In the background, Tuscan hill flora. Downstairs, in the Restoration Studio, I remove five centuries of grit, oxidized pigment. X-rays show which strokes licked the apprentice’s brush, which the master’s. I add cerulean to her robe, carnelian to his. Reconfigure a shadow. Mike Ross Mike Ross teaches courses in poetry writing at the Osher Lifelong Learning Institute at UNC Asheville. His first book of poems, Small Engine Repair, was published in 2015. He is working on a second book of poems. Chez Le Père Lathuille

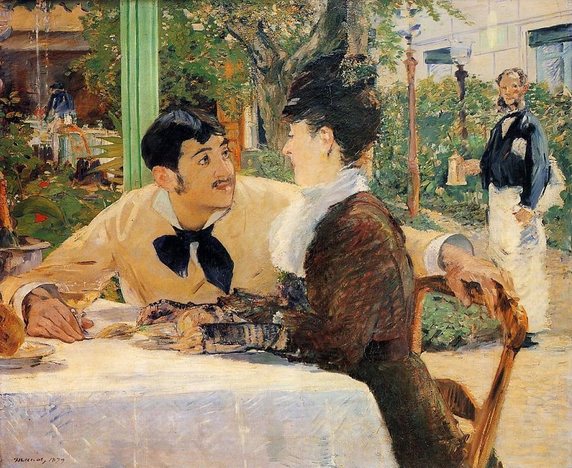

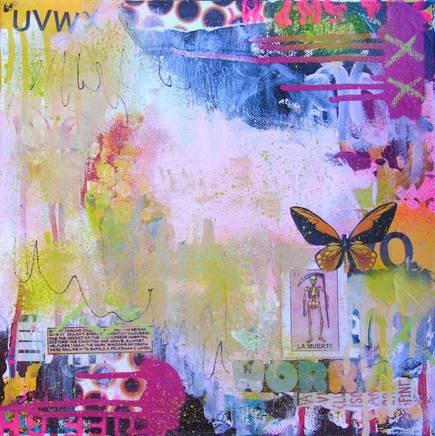

It’s lunchtime on a sunny day in early October, when Claire, a wealthy widow with a stern demeanor, sits at a table on an expensive Paris restaurant patio with her grown son, Henri. An eager young man with a crooked black neck tie, Henri leans in, places his left arm on the back of his mother’s chair, as eye to eye he draws her near. Henri’s fingers wrap the stem of his half-filled glass of chilled Sauvignon Blanc, almost gold in the sunlight, as he begins pleading his case… Claire listens to Henri’s calculated appeal, poised, and regal, in her hat with the sweeping black feather, matching her black hair. Does Claire’s stern expression conceal her belief that Henri seems sincere? Sun and lush foliage frame the measure of their every word, and every gesture. Jacques, a sidelined stoic, ready perhaps, even anxious to serve, stands just within earshot, a thin man with a receding hairline, and a complex, small gold pitcher in hand. When Jacques notices Henri’s half-filled glass, he dares not interrupt Henri’s plea. Instead, he waits like a statue, intrigued by Claire, her straight posture, and serious face. Jacques keeps his hand in his pocket, taking notes with his eyes as he tunes in with envy to Henri’s attempt to persuade his mother… Tired legs, and feet that ache, Jacques laments his poor lot in life through an old script about how he blew the chance to own the restaurant he serves. Though beyond his ability to explain, Jacques knows from experience, false steps cripple, ill-timed words wound, and all deeds feed the deeds that follow… He fears his approach to the table might cast a shadow on Claire’s attention, and jinx Henri. So, he keeps his distance, and the well-positioned widow ignores him. But what the Far East calls karma, or science calls The Butterfly Effect, Jacques’ doctor in nineteenth century France, views as a few of his crazy ideas. Never one to act with haste, Claire motions for the check and buys time to decide… As they leave, she suggests they continue their talk next week in a nearby café. Perhaps, as they exit through the patio, Henri decides to free his thoughts of her, until they meet again… Obsessed with the vision of Henri’s half-empty glass, Jacques’ fidget becomes a nervous pace, his thoughts race back and forth in time with his feet. For the rest of his shift, Jacques broods and berates himself. If he’d offered to refill Henri’s glass, what might Claire have decided, as Henri sipped? Would he ever know? Could he ever know? Maybe his encounter with Henri and Claire, embeds a new syllable or two in Jacques’ familiar script. Michele Harvey Michele Harvey’s poems have appeared in several literary publications including: Vine Leaves Literary Journal, Progenitor, Copper Nickel and The Litchfield Review. Her sonnet, “Dinosaur Ridge,” is the focal point for a permanent art in public places display at the Jefferson County Government Center railway station in Golden, Colorado. Michele Harvey is the author of Poetry for Living an Inspired Life. La Muerte Mariposa, why do you flirt with Death? You make a good couple, I freely admit it -- he with his yellow bones and steely scythe, you dressed in yellow and orange and lots of funereal black. Perpetual Día de Muertos! But one day he’ll play the death card on you, you know. Perhaps you should worry a bit. Reconsider. Meanwhile, enjoy your denim-and-polka-dot daydreams, your blushing-pink and acid-green world. Oh, what the hell! Do the danse macabre -- click your castanets while he rattles his bones! The shadow of Death hangs over us all anyway. Besides, even a skeleton has dignity. Even a dead butterfly is still beautiful. Bill Waters Bill Waters is a well-published writer of short poetry and compressed prose. He also runs the Poetry in Public Places Project, a Facebook / real-world group interested in creating and promoting poetry in public spaces to increase the richness of everyday living. Bill lives in Pennington, New Jersey, U.S.A., with his wonderful wife and their two amazing cats. See more artworks from Lorette C. Luzajic, editor of The Ekphrastic Review, here. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

Tickled Pink Contest

April 2024

|