|

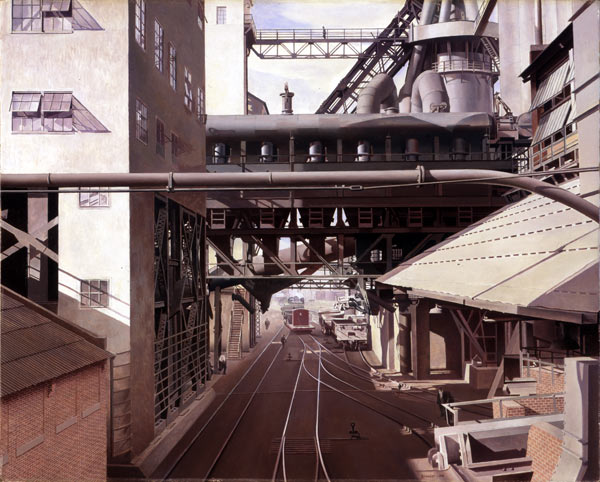

City Interior

The painting is precise, photographic. It features industrial buildings with paned windows, a few propped open to release fetid air. It shows aluminium pipes and rivets, steel cables and junctions. The brickwork is meticulous. The perspective is definitive: five railroad tracks converge a third of the way up the picture - linking the world outside this painting to the dead centre of the canvas - and then they slip away into the bright indistinctness of the distance. This is a street in the heart of Detroit depicted in grey and sepia. The people in the painting are almost invisible by virtue of both size and colour. One by one they emerge, three men heading away along the front of the building on the left hand side, two men lower down to the right - a white man glancing back at an African American man. Starting a conversation? Ending one? Staring blankly through him? And then there’s the man anyone would miss, high overhead in the centre of the painting, walking across a gantry. The hatching on one of the steel cross members is detailed, the shadow of a window intricate, yet the people are indistinct pokes of a brush, almost incidental. This is the 1930s when Ford’s mechanisation of manufacture is king and men are ten a cent. While agricultural land decays into dust, this street in Detroit is pristine. Imagine a woman coming into the bottom right hand of this picture, an African American woman in a place where even the men barely belong. Perhaps she is heading towards the African American man - his wife or sister? But she ignores him, as though he is invisible, and steps over each of the tracks with a flick of her heel. And just as we think she is going to speak to the man in white shirt, we are startled to discover a seventh man, one with only one leg and one arm protruding from behind a vertical iron girder, his face barely visible under the peak of his cap. He is painted from the same blend of grey oils as the girder he is half-concealed by, and now we have seen him we wonder how we could ever have missed him, for it is this man that the woman is staring at as she purposefully crosses from right to left. “Frank.” The woman calls the name that she has used ever since the days when he delivered blocks of ice cut in winter from the great lakes and transported south by cart, by wagon, by train till they finally reached Plainfield. On the back stoop of Mrs Kennedy’s house she waited to watch as he took a saw to the dripping giant on the back of his truck, resting the off-cut on the wet piece of sackcloth slung over the shoulder of his leather vest. “Hoo-whee,” he said. “It’s a hot one.” And he raised a hand to his forehead, pretending to let the ice block slip, winking as she reached forward to prevent the contrived catastrophe. “Would you like me to set this in the ice box for you, Hattie?” In the painting the man doesn’t so much as smile, he glances around to see if any of the other men have noticed a woman in their midst, an African American woman at that, one who is now talking to him. He puffs out and then says, “Why you here?” “Sorry, Mister Finch.” She shouldn’t have called him Frank just now. She realises that in this formal city the codes that were bent on a back stoop are as absolute as the iron work surrounding them. She knows how the rules of this painting work. She adjusts her glove, hoping he won’t notice where the thumb and forefinger have worn through, and whispers, “It’s concerning your brother, Mister Finch.” And she searches the grey face shaded by the cap for a reaction, remembering when that face was sun-reddened, when the eyes reflected the blue sky and the cheek bones the white sun. She remembers the time before refrigerators reached Plainfield when ice came with a kiss and a tingle, when hands were held out of sight, the time when people had food in their ice boxes and stomachs. But the man won’t look at her. “Ain’t he dead?” he says. Hattie twitches her elbows to her sides, holding her purse firmly in her gloved hands, and notices the indent of a bristle across his forehead which speaks of guilt. He hasn’t written to his family back in Plainfield, not since who knows when. Now Hattie is here she partly understands why. Things are different here. There can’t be much to say about attaching fenders to automobiles, about precision. She’s got plenty she could tell this Mister Finch about Plainfield if he wanted to know, how the store’s closed down, how the cattle are all gone, how Mrs Kennedy moved to live with her sister somewhere in this city. “No, sir,” she tells him. “He ain’t dead.” The man straightens, but still remains in the shadow where he has been painted. His brother isn’t dead. All is well. No need to talk to her any more. He stares over her hat and Hattie is caught between one leg and the other, not comfortable on either. Not happy at being here in this painting at all. “He, Mister Finch, the other Mister Finch.” Hattie pauses. “It’s my sister Minny. You remember her, sir?” He nods. “Mister Finch, well he’s gone and, and now Mrs Gregory has let her go and she can’t feed herself let alone a baby. She gonna starve, Mister Finch, and he, the other Mister Finch, he don’t wanna know nothing at all. So I was wondering, whether you could see your way to giving her a dollar or two, just a bit, to keep her, for a little, till the baby comes.” The man pushes tightly to the girder. The man in the white shirt moves on obliviously, permanently in half-step, and the man on the gantry looks down on the scene, tapping the ash of a Marlboro. He doesn’t really have a role to play, just stuck up there by the painter to break the skyline. “I thought you might, you know, after, well,” she looks down. She wouldn’t be asking at all if it weren’t Minny, barely grown up enough to work let alone anything else, all skin and bones as it is. “Nooo,” he says slowly, shaking his head. Plainfield is as far away as the other side of the gallery. What happened back there, back then, means nothing, not here. “She’s carrying your blood,” Hattie says. He shifts, as though deciding on something. “I’ve got me a plan you see, Hattie,” he says. “Get me a tyre shop, make a little money. Need every cent I earn for my plan, I do. Can’t go sending none to Plainfield.” He settles back. He belongs here now, this is his world. “Could have been us,” she says, wishing she didn’t have to say it out loud, even if her voice is no more than a gallery whisper. “I could tell them that.” The man shakes his head. “Makes no odds to me,” he says. Hattie looks around at the scene depicted in this barely more than monochrome painting. The almost incidental people pictured are here for good, stuck together for ever, each alone. Who here cares about anything beyond the frame? And even though he is the man and she is the woman, he is white and she is African American, he has money and she has none, she feels sorry for the half-man the ice man has become. Ruth Brandt Ruth Brandt’s short stories have appeared in anthologies and magazines, including Aesthetica Creative Writing Annual 2017, Bristol Short Story Prize Vol 4, Litro, and Neon, nominated for prizes including the Pushcart Prize 2016, read at festivals and performed. She lives in Woking, England and has two delightful sons. www.RuthBrandt.co.uk

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|