|

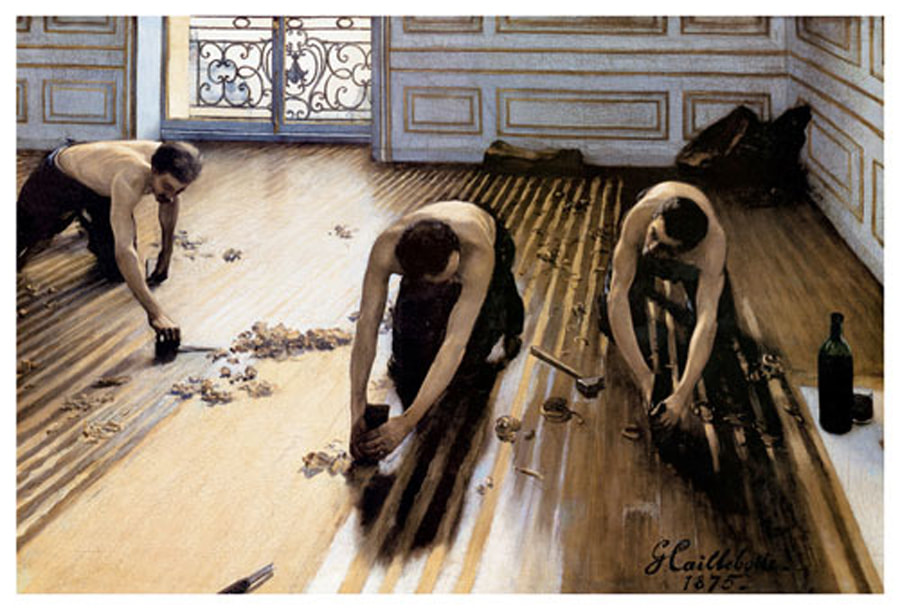

Against the Grain So, Charlotte: finally, I see the completed painting, and I wish you could see it with me. It is larger than I thought, yet looks small in this mausoleum of a building. The doorman’s look of disgust made plain that The Louvre is not for the likes of me. You would hate the cold inside, too, Charlotte, just as you hated winter. The painting is clear as one of these modern-day photographs, in the same grey-brown tones. If only you had lived to see it, my love. Memories weigh my eyes down so heavy I can hardly look. Then, like a shy lover, I can't resist. Look! Look how the light fell through the window and stroked the floorboards. I feel the heat of that summer all over again. Look at the line of my muscles. You always told me I was strong. Now I understand. 'Robert - the light will illuminate the curve of your shoulders - along here,' Monsieur explained, running his finger along my back. I said nothing. How could I speak when it was all I could do not to shiver? The old pain rises in my chest. It’s jealousy – of the love that Monsieur showed to you, and jealousy that I must share this painting with those other men. I am in the background. ‘The viewer’s eye will be drawn to you because of the Golden Section,’ Monsieur told me. Whatever that meant. At least he chose to show more of my body. Perhaps I meant something to him. We three were on our hands and knees, working. Those two whispered, heads together, and I was never a part of it. Except we didn’t work. Really, we posed while Monsieur sketched us. Floor scrapers. Humble workmen, and he painted our picture. We were all stripped to the waist, and Charlotte, it’s my body you see the best in Monsieur’s painting. The heat that summer was intense. Sweat pooled between our shoulder-blades, in the small of our backs, it ran down our faces and dripped from our noses. We wiped them on our shirtsleeves until Pierre swore and stripped off his shirt. We copied him. Only the poor, or the stupid, worked that hot August afternoon in Paris. The heavy air muffled the sound of a carriage from the boulevard outside. Wood-dust hung in shafts of sunlight. It coated our sticky bodies, the insides of our mouths and noses, and blanketed the wooden floor in a thick layer, swept into uneven piles by the shuffle of our trouser knees. We worked in silent rhythm, a soft hissing outbreath escaping from our scrapers as the wood spiralled into curls. Jean-Luc filed the blades of our planes to a tiny burred hook on one side – he had skill in that - so we could shave the thinnest of slivers from the wooden floor. We were not aware of Monsieur watching us, leaning in the door frame. 'Would you care for wine?' His voice was the caress of a brush on canvas. Pierre jumped to his feet and grabbed his shirt. 'No, no. Not on my account - it's too hot. Keep your shirts off.' Monsieur brought us a bottle and three glasses himself. We sipped a little, but, with his eyes still on us, we returned to work, crawling up and down the floorboards like black beetles, along the grain, our scrapers rasping the floor. His followed our bodies like wood dust stuck to our sweat, yet I could not look at him. I wanted him to watch me, but did not understand why. I scratched at this new thought in my mind: scraped the layers away, until I dug against the grain into the floorboard with my scraper and I knew I must concentrate harder. 'Call me Gustave,' said Monsieur. As if I, or Jean-Luc, or Pierre, could ever call him anything other than Monsieur. 'I am an artist,' he said, 'and this room is my studio.' This room - this huge room - bigger than all our rooms put together with the neighbours, Charlotte! I thought an artist would have wild hair and beard, and be spattered with paint. This man was neat and small with a narrow, unexceptional face and he wore his grizzled hair cropped short. ‘Whoever heard of working men having their picture painted?’ Pierre grunted, later, after Monsieur asked to paint us. ‘He’s paying us well,’ said Jean-Luc. ‘Are you in or out, Robert?’ ‘In,’ I said, my tongue thick. I wanted so much to be watched by this artist, this Gustave. ‘Me and Charlotte need extra money,’ I added. ‘I’d give Charlotte extra’ said Pierre, and I laughed so he did not despise me, but I felt sickened by his talk. And, next morning, when we arrived in the Rue Meromesnil apartment, a fresh bottle of wine and three glasses waited on the tray. Monsieur arrived too, and stood in the doorway watching. My heart hammered in my ears. I lowered my eyes and stayed silent of course. Such a fire burnt inside me that a single spark could have caused a blaze in the wood shavings. Monsieur scrutinised us from behind an easel set by the door. We crept up and down between the lines like caged animals. I would have roared for him. He came into the room and reached towards me. ‘Stretch out your right arm, Robert, if you please,’ he said, and smiled. His smile was so large, it was like the sun shone out from his face. ‘Now press down… to define the muscle.’ He took my hand and moved it over the wood. I shivered, despite the heat, despite my best intentions. ‘Of course, you’re tiring,’ said Monsieur, crouching behind me and reaching his arm across my back. ‘You’re not used to modelling for an artist. Breathe easy. Now roll your arm out from the wrist a little. Take more weight onto your left arm. Now keep still.’ The next day Monsieur asked me to stay behind after the others left. My longing blazed on my cheeks. Monsieur positioned me on the floor, on hands and knees like in the painting. His hand lingered on the nape of my neck. 'Don't move,' he said, breath warm on my ear. He moved away to his easel and seconds passed, maybe minutes, maybe hours. Pins and needles prickled in my hands and arms. Monsieur had finished, he said. I was frozen in the heat. Stuck, like an old man. He helped me to my feet, his hands either side of my body. I longed for him to put his arms around me, and burnt with shame that I should crave such a thing. He held me firm by my shoulders, smiled his big smile and I fell into the intense blue of his eyes. 'You are perhaps dizzy, Robert? Sit here awhile.' He led me to a chair and handed me my shirt. I could barely button it up. Sitting beside me, he took my hands. I concentrated on keeping still, on keeping my breathing steady. He lifted each of my fingers in turn - to get the details right, he said. My hands were grimy and brown, calloused and larger than his, with ugly chewed nails. I was felt ashamed of my workman’s hands. Monsieur asked where I lived, said he’d have someone bring me my payment. That evening, Charlotte, though I never said, I was not surprised when he delivered my money himself. Neither was I surprised that you read my mind and invited him in for wine, though you had never asked in my friends before. We three sat at our rough wooden table, in our tiny room, Monsieur with the one good glass and you and I with mismatched ones. We turned the chipped edges away from him, without need for words. He was polite and kind, putting us at ease with his wide smile and sparkling eyes. We both drank our wine too quickly, but Monsieur hardly touched his – too coarse, I suppose. He talked, with wit and gentleness, looking first at me, then at you, Charlotte, drawing us in to him with his words, hypnotising us. I dragged my eyes away from him and looked at you. You glittered like sun on running water. You leant forward, chin on hands, elbows on the table. Your eyes were locked onto his, and you were imprisoned in a mutual smile. Your brown curls waterfall down your shoulders and candlelight danced in your dark eyes. Your delicate white hand drifted up to your mouth, as if your happiness was more than could be contained in your face and it spilled over. Monsieur leant on his elbow and smiled too, that smile which transformed his face into handsomeness, an upturned curve such as a child might draw. And you, Charlotte, you basked in its warmth, your face tipped up the way you lifted your face to the sunshine after winter. And then, it came to me with painful certainty, that for you both, I was not present. You had not read my mind, after all. It came to me that Monsieur’s big smile was for you alone. That this entrancing murmur was for you, he had already forgotten me. I gulped the dregs and banged my glass onto the table, but neither of you noticed. In that moment, I lost what might have been for the first time, and the shadow of that loss resides in me still. Monsieur never painted you, Charlotte. Always me. I learned never to ask where you’d been and when you were coming home. You were still my best friend; my wife, the only one who understood how my truest feelings went against the grain. I comforted you at his passing, and we cared for each other all those years after he was gone. And now you’re gone too, Charlotte, and all that’s left of we three is hidden in this painting, in this cold room. And outside, a fresh layer of snow hides the icy boulevard. Helen Chambers Helen Chambers has been published widely, including in the Citron Review, Spelk, The Drabble, and Potato Soup Journal. https://helenchamberswriter.wordpress.com/writing/

4 Comments

jo m Goren

12/29/2019 12:15:19 pm

Helen, I like the mystery and sadness of your story.

Reply

1/7/2020 06:56:09 am

Thank you Jo. I’m not sure if we should admit to having ‘favourites’ amongst what we write - but this one is!

Reply

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|