|

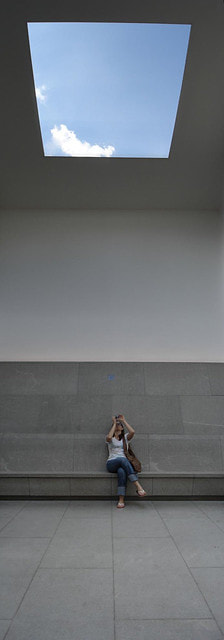

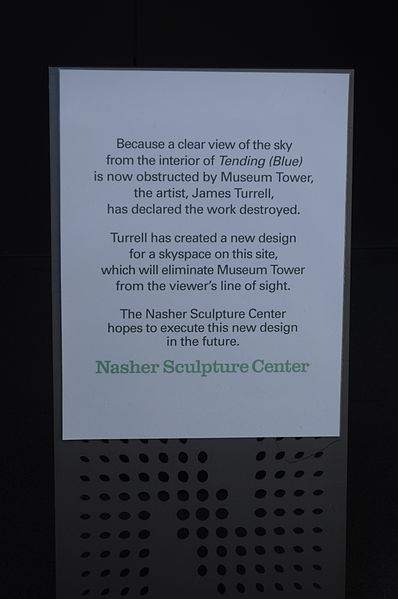

Tending (Blue) Don’t come to Paris, read the message from Henri, and Camille knew that he was no longer hers. Already in her hometown of Dallas for the transatlantic flight—having driven that morning from Waco, where she now lived—she chose to stay so that she could sleep in her childhood bed. The next morning, she sought out the sculpture garden, noting with relief that it was empty of patrons, save for a mother and toddler. Camille pulled her Hermès scarf, a gift from Henri, over her hair, ducked her head, and skulked to the back of the park, toward the dark granite structure of Turrell’s Tending (Blue). Its interior, she knew, was bathed in luminous white, a sensory deprivation tank pierced only by a square of blue above, the sky visible through a window in the ceiling. If no one else was inside, Camille could curl into a fetus in the artwork’s womb, peering from the corner of her eye at the eternal blueness above. But once at the entrance, she saw the doors chained shut; a posted sign declared, Because a clear view of the sky from the interior of Tending (Blue) is now obstructed by Museum Tower, the artist, James Turrell, has declared the work destroyed. Camille confronted the offending condominium—a glass and steel exclamation point newly punctuating the sky—then sank to a bench near Tending (Blue), now a sealed mausoleum. Hepworth’s neighbouring Monolith stood vigil, a tombstone. Beyond, Rodin’s Eve turned away, her right arm curved protectively around her body, her left hand shielding her face from Tending’s chained gates. Even Maillot’s La Nuit slumped, bereft, head buried in arms. Camille sat, irresolute, till strident cries from a blue jay and a splashing noise from a nearby pool pierced her consciousness. Even so, she ignored the noise, instead watching the mother at the garden’s opposite end as she guided her child up the exit stairs. The jay’s shrieks persisted, and now Camille noticed the distressed bird. Its offspring lay in the water just along the pool’s edge. She removed her scarf and scooped up the fledgling, its new feathers heavy with water. She returned to the bench, resting the bird in her lap. She cradled the juvenile jay in the warmth of her scarf, stroking the bird’s still body and murmuring to it softly, “Breathe, breathe.” All along, its mother worried loudly from branches above. Slowly, the baby jay revived. Between her palms, Camille felt its fragile frame—all heartbeat and skeleton—as it twitched. Opening its black eyes, the bird wriggled in surprise, then stilled itself in the scarf’s silk folds. Camille lowered the baby blue jay to the ground, backing away so its mother had wide berth to reclaim her chick. After chiding Camille soundly, mama coaxed baby into nearby ivy, where they disappeared. Camille turned back to Turrell’s locked doors and threaded her scarf amidst their chains, realizing she mourned the loss of Tending (Blue) more than that of Henri. Michelle Kraft Michelle Kraft is an art professor in Texas who has traveled extensively with university students, shuttling them throughout Texas, New Mexico, and Europe so that they can see firsthand the works they would otherwise only study in art history textbooks. While she has several scholarly publications, Michelle is relatively new to creative writing and is especially intrigued by the notion of how place informs experience and identity. Her work can be found in such journals as Visual Arts Research, Visual Culture & Gender, The Bowerbird and The Menteur.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|