|

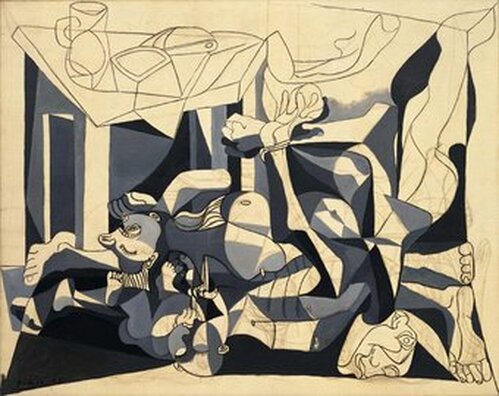

The Charnel House Oliver didn’t think about art, not that he had anything against it. It was just something he had never paid attention to while growing up. His mother painted watercolours, but he never considered her paintings art. Painting was simply what she did in her spare time. It was a hobby. Once when he was seven his aunt took him to see a Van Gogh exhibit. She told him that Van Gogh had a mental illness that accentuated his creativity, but she didn’t explain why anyone would be interested in seeing the paintings of a mentally ill person. It was the same with Picasso. Everyone said he was great, but no one explained why. When Emily, a friend from work, asked if he wanted to come with her to see a Picasso exhibit, he wasn’t sure what to say. Two weeks before, he and Emily had gone to lunch at a café in the Mission District. He found her attractive, interesting. She talked about art, music, and nature, plus she was funny, and seemingly passionate about everything. When she asked about going to the exhibit, he admitted he knew nothing about art. But the more she talked about it, the more he wondered if he could learn what made Picasso great. But more importantly, he wanted to spend time with her. The exhibit was called Picasso and the War Years, a collection of paintings produced before and during the Second World War. As the two of them walked from one room to another in the museum, Oliver found the paintings confusing and disturbing. He saw a grotesque dancer with distorted limbs holding a tambourine. He saw squiggly lines that suggested a bird from one perspective and a three-eyed woman from another. Another painting showed a bizarre looking female with an ear where her nose should be and a nose stuck to the side of her face. And skulls. There were human skulls, sheep skulls, and cow skulls. What was the point? he wondered. Oliver glossed over the exhibit brochure and read that Picasso was the greatest artist of the 20th century. He assumed the museum people must know something, but nothing in the exhibit looked remotely familiar. There were no trees or mountains or cows in a field or portraits of normal looking people. The paintings seemed to have come from the mind of a madman. No other explanation made sense. He was clearly out of his element and began to think he’d made a mistake. Emily marveled at paintings he couldn’t possibly comprehend. Clearly it had been a bad idea to go with her to a museum. A woman like her would never be interested in someone like him. Oliver was anxious to get through the exhibit as quickly as possible. Emily wanted to take her time and study each piece. They agreed to meet later in the bookstore. Oliver walked quickly through the next room glancing at portraits of strange, hideous figures. Dark, unexpected colors on contorted faces, many of whom appeared to be weeping. One figure was painted green. Several were little more than unorganized scribbles. One showed a nun in black with an exposed breast and her arms raised. Another depicted a screaming woman holding a dead child. The only concession Oliver could make was that the subjects and colors were bold. He stepped into a room with a full-sized reproduction of Picasso’s most famous painting. The sweep of Guernica captured him. He stopped to take it in. A horse in agony. Dead and dying people. A ghostly figure coming into the house holding a lamp. A bull with demonic eyes. Oliver didn’t know what the painting represented other than a depiction of war. He took a deep breath and moved to the last room of the exhibit. This room was dominated by a single painting more disturbing than the others. He stepped close to read the label – The Charnel House – then stepped back. It was gray and black with exposed, raw, yellowed canvas. The painting appeared like an open window, as though he was looking through onto a horrific pyramid of broken bodies, including that of a small child. They reminded him of overripe, rotting fruit, discarded refuse. In the lower part of the painting the light was dying, falling to angular pools among the bodies, into blackness at the edges. The drawn and painted figures were stripped, tortured, and bound. He noticed erasures of earlier, forgotten deaths. These figures, he realized, were the victims of every war, buried under a table of undeniable abundance with a pitcher, probably of wine, and a loaf of bread. The label stated that Picasso had intentionally left the painting unfinished, since the brutality and senselessness of war hadn’t ended when Picasso stepped away from it. Oliver found that he couldn’t take his eyes from it, especially the large unpainted areas of the canvas. Perhaps because there was less brutality in the empty spaces. Perhaps because he felt safe resting his eyes there. Perhaps because they reminded him of the same soft yellow of the mud house outside of Kandahar, the one he had entered minutes ahead of his team members. Oliver walked slowly through a courtyard surrounded by mud walls. A dawn rocket attack had destroyed most of the village. It was believed that the houses had been abandoned and insurgents were using them to store weapons. This house was one of the few still standing, although its wooden door had been blown in. As he approached, he heard the sound of someone crying. Oliver knew only a few phrases in Pashto. He called out tas-leem saa, the phrase for “surrender.” No one answered. He said it again. When there was no response, he called out in English, “come out.” Still nothing. He stepped to one side of the opening and shined a light into the room. The crying sounded like that of a child. Slowly, he stepped through the door and swung the barrel of his rifle across the room. He stopped at the sight of a small child, a girl, sitting on the floor next to a dead woman, probably the child’s mother. The woman was lying contorted on the floor in a pool of drying blood. As the other team members entered, Oliver turned and ran out of the house. He turned away from the painting and closed his eyes, but the crying didn’t stop. He found it difficult to breathe. He looked behind him, saw a long wooden bench, and sat down. Then he glanced around the room. There were no children in the room, just an elderly woman sitting on the far end of the bench. He turned toward her. “Do you hear someone crying?” The woman looked at him, shook her head, and turned back to the painting. Oliver didn’t understand what was happening. The sound was so clear. Was it coming from the painting? He looked again at it and wondered if the canvas, paint, and imagery had entered his head. He felt a flash of anger at Picasso, as if the artist had used his brush as a weapon and Oliver himself had become the target. The crying seemed to grow louder. “Oliver?” He jumped at hearing his name. It was Emily. He stood quickly and smiled an embarrassed smile. “Are you alright?” she asked. “Fine, fine,” he said, rushing his words. “It’s... a remarkable exhibit. I’ll wait for you outside if that’s alright.” “Sure,” she said, puzzled by his abrupt behavior. She watched as he quickly left the room. Then she turned and looked at the painting. She wondered why Picasso had left it unfinished. Jim Woessner Jim Woessner is a visual artist and writer living on the water in Sausalito, California. He has an MFA from Bennington College and has had poetry and prose published in numerous online and print magazines, including the Blue Collar Review, California Quarterly, and Close to the Bone. Additionally, two of his plays have been produced in community theatre.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

The Ekphrastic Review

COOKIES/PRIVACY

This site uses cookies to deliver your best navigation experience this time and next. Continuing here means you consent to cookies. Thank you. Join us on Facebook:

July 2024

|